Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darwin Initiative for the Survival of Species Annual Report

Darwin Initiative for the Survival of Species Annual Report 1. Darwin Project Information Project title Establishment of Penguin Monitoring Programme Country(ies) Chile Contractor Environmental Research Unit Project Reference No. 162/9/007 Grant Value £10,350 p.a. for 3 years Start/Finishing dates April 2001 to March 2004 Reporting period April 2003 2. Project Background • Briefly describe the location and circumstances of the project and the problem that the project aims to tackle. The project takes place on Magdalena Island, near the city of Punta Arenas in southern Chile. Magdalena Island is one of Chile’s most important breeding sites for Magellanic penguins, a species whose global distribution is restricted to southern South America. Best guess estimates put the current world population of Magellanic penguins at around 1.5 million breeding pairs, with approximately 700,000 pairs in Chile, 650,000 pairs in Argentina and 150,000 pairs in the Falkland Islands (Bingham 1998, Bingham & Mejias 1999, Gandini et al. 1998). Population studies in the Falkland Islands conducted by Mike Bingham have revealed an 80% decline in Magellanic penguins between 1990/91 and 2002/03. A reduction of fish and squid resulting from large-scale commercial fishing appears to be the cause of the penguin decline, through reduction of foraging rates, breeding success and juvenile survival (Bingham 2002). Population studies conducted in Argentina show evidence of decline at some colonies, but not all (Boersma 1997). Declines in Argentina appear to be largely the result of high adult and juvenile mortality caused by oil pollution. An estimated 40,000 Magellanic penguins are killed by oil pollution every year along the coast of Argentina, representing the main cause of adult mortality (Gandini et al. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

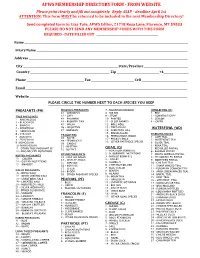

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - from WEBSITE Please Print Clearly and Fill out Completely

APWS MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - FROM WEBSITE Please print clearly and fill out completely. Reply ASAP – deadline April 1st ATTENTION: This form MUST be returned to be included in the next Membership Directory! Send completed form to: Lisa Tate, APWS Editor, 21718 Kesa Lane, Florence, MT 59833 PLEASE DO NOT SEND ANY MEMBERSHIP FUNDS WITH THIS FORM REQUIRED - DATE FILLED OUT ______________________________________________ Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Aviary Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Address _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ City ________________________________________________________________________ State/Province _________________________________ Country ___________________________________________________________ Zip ________________________________+4___________________ Phone ___________________________________________ Fax ________________________________ Cell __________________________________ Email _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Website ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PLEASE CIRCLE THE NUMBER NEXT TO EACH SPECIES YOU KEEP PHEASANTS (PH) PEACOCK-PHEASANTS 7 - MOUNTAIN BAMBOO JUNGLEFOWL -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

Guia Para Observação Das Aves Do Parque Nacional De Brasília

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234145690 Guia para observação das aves do Parque Nacional de Brasília Book · January 2011 CITATIONS READS 0 629 4 authors, including: Mieko Kanegae Fernando Lima Favaro Federal University of Rio de Janeiro Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Bi… 7 PUBLICATIONS 74 CITATIONS 17 PUBLICATIONS 69 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Fernando Lima Favaro on 28 May 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Brasília - 2011 GUIA PARA OBSERVAÇÃO DAS AVES DO PARQUE NACIONAL DE BRASÍLIA Aílton C. de Oliveira Mieko Ferreira Kanegae Marina Faria do Amaral Fernando de Lima Favaro Fotografia de Aves Marcelo Pontes Monteiro Nélio dos Santos Paulo André Lima Borges Brasília, 2011 GUIA PARA OBSERVAÇÃO DAS AVES DO APRESENTAÇÃO PARQUE NACIONAL DE BRASÍLIA É com grande satisfação que apresento o Guia para Observação REPÚblica FEDERATiva DO BRASIL das Aves do Parque Nacional de Brasília, o qual representa um importante instrumento auxiliar para os observadores de aves que frequentam ou que Presidente frequentarão o Parque, para fins de lazer (birdwatching), pesquisas científicas, Dilma Roussef treinamentos ou em atividades de educação ambiental. Este é mais um resultado do trabalho do Centro Nacional de Pesquisa e Vice-Presidente Conservação de Aves Silvestres - CEMAVE, unidade descentralizada do Instituto Michel Temer Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio) e vinculada à Diretoria de Conservação da Biodiversidade. O Centro tem como missão Ministério do Meio Ambiente - MMA subsidiar a conservação das aves brasileiras e dos ambientes dos quais elas Izabella Mônica Vieira Teixeira dependem. -

Parallel Evolution in the Major Haemoglobin Genes of Eight Species of Andean Waterfowl

Molecular Ecology (2009) doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04352.x Parallel evolution in the major haemoglobin genes of eight species of Andean waterfowl K. G. M C CRACKEN,* C. P. BARGER,* M. BULGARELLA,* K. P. JOHNSON,† S. A. SONSTHAGEN,* J. TRUCCO,‡ T. H. VALQUI,§– R. E. WILSON,* K. WINKER* and M. D. SORENSON** *Institute of Arctic Biology, Department of Biology and Wildlife, and University of Alaska Museum, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA, †Illinois Natural History Survey, Champaign, IL 61820, USA, ‡Patagonia Outfitters, Perez 662, San Martin de los Andes, Neuque´n 8370, Argentina, §Centro de Ornitologı´a y Biodiversidad (CORBIDI), Sta. Rita 117, Urbana Huertos de San Antonio, Surco, Lima 33, Peru´, –Museum of Natural Science, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA, **Department of Biology, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215, USA Abstract Theory predicts that parallel evolution should be common when the number of beneficial mutations is limited by selective constraints on protein structure. However, confirmation is scarce in natural populations. Here we studied the major haemoglobin genes of eight Andean duck lineages and compared them to 115 other waterfowl species, including the bar-headed goose (Anser indicus) and Abyssinian blue-winged goose (Cyanochen cyanopterus), two additional species living at high altitude. One to five amino acid replacements were significantly overrepresented or derived in each highland population, and parallel substitutions were more common than in simulated sequences evolved under a neutral model. Two substitutions evolved in parallel in the aA subunit of two (Ala-a8) and five (Thr-a77) taxa, and five identical bA subunit substitutions were observed in two (Ser-b4, Glu-b94, Met-b133) or three (Ser-b13, Ser-b116) taxa. -

Bleaker Island Settlement & the South

Distance: 1.5 - 2 km Time: 30-45 min Terrain: Moderate 1 SETTLEMENT TRAIL 89 Semaphore Hill This short trail is ideal for families and provides a great introduction to the immediate area. Taking in whale bones, settlement buildings and gardens, the walk also provides a glimpse into farming life with the chance to watch farm activities such as shearing or cattle work if the time is right. It includes a short climb to the Shearing shed summit of Bleaker’s highest hill, an altitude of just 27m (89 feet), giving views across the island and surrounding ocean. 1 Main route Settlement Walk first to the BBQ hut in front of Cassard House. BBQ hut Take time to admire the “Essence of our Community” Imperial artwork on the south-facing wall then go through the gate cormorants Long to see a full Sei whale skeleton, above the beach, nestled 0 100 200 300 400 500 Gulch into the green. 2 Meters From here a route can usually be picked out along the Rockhopper shore in a northerly direction towards the shearing shed Short Gulch penguins and stock yards, taking in a pretty little bay with a variety First Is. of birds. If the weather is very wet and the shoreline muddy, Pebbly Bay an alternative is to walk back through the gate by the Tips: bar-b-que hut, down through the low valley via the wind Ask if anything is happening on the farm, to turbine and solar panels, then through two time the walk accordingly, but remember to gates along a clear track. -

Nesting Biology. Social Patterns and Displays of the Mandarin Duck, a Ix Galericulata

pi)' NESTING BIOLOGY. SOCIAL PATTERNS AND DISPLAYS OF THE MANDARIN DUCK, A_IX GALERICULATA Richard L. Bruggers A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1974 ' __ U J 591913 W A'W .'X55’ ABSTRACT A study of pinioned, free-ranging Mandarin ducks (Aix galericulata) was conducted from 1971-1974 at a 25-acre estate. The purposes 'were to 1) document breeding biology and behaviors, nesting phenology, and time budgets; 2) describe displays associated with copulatory behavior, pair-formation and maintenance, and social encounters; and 3) determine the female's role in male social display and pair formation. The intensive observations (in excess of 400 h) included several full-day and all-night periods. Display patterns were recorded (partially with movies) arid analyzed. The female's role in social display was examined through a series of male and female introductions into yearling and adult male "display parties." Mandarins formed strong seasonal pair bonds, which re-formed in successive years if both individuals lived. Clutches averaged 9.5 eggs and were begun by yearling females earlier and with less fertility (78%) than adult females (90%). Incubation averaged 28-30 days. Duckling development was rapid and sexual dimorphism evident. 9 Adults and yearlings of both sexes could be separated on the basis of primary feather length; females, on secondary feather pigmentation. Mandarin daily activity patterns consisted of repetitious feeding, preening, and loafing, but the duration and patterns of each activity varied with the social periods. -

Viruses in Migratory Birds, China, 2013–2014

Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2206.151754 Novel Avian Influenza A(H5N8) Viruses in Migratory Birds, China, 2013–2014 Technical Appendix Materials and Methods Wild Bird Surveillance and Sampling Wild birds were captured and sampled with the permission and supervision of Shanghai Wild Life Conservation and Management Office. Swabs (1 oropharyngeal and 1 cloacal of each bird) were taken and transported in viral transport medium to the laboratory at 4°C for downstream molecular diagnosis within 6 hours. Virus Detection Viral RNA was extracted from viral transport medium by using MagMAXTM Pathogen RNA/DNA Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) on a Magmax-96 Express (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real time reverse transcription-PCR was performed with matrix gene–specific probed primers to detect the presence of avian influenza viruses according to the protocol of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (1). The results were further confirmed by sequencing the PCR products. Subtype Identification and Gene Sequencing RNA of viral-positive samples were reverse-transcribed by PrimeScript II Reverse Transcriptase Kit (TaKaRa, Biotechnology [Dalian] Co., Ltd, Dalian, China) according to the kit protocol. PCR amplifications were performed for subtyping of hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase, and gene segments were amplified by using the previously published primers (2– Page 1 of 5 4) and primers designed in this study (on request). PCR products were gel-purified by using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA) and were sequenced with the BigDye terminator kit (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI 3730 (Applied Biosystems). -

Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 SOUTHEAST BRAZIL: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna October 20th – November 8th, 2016 TOUR LEADER: Nick Athanas Report and photos by Nick Athanas Helmeted Woodpecker - one of our most memorable sightings of the tour It had been a couple of years since I last guided this tour, and I had forgotten how much fun it could be. We covered a lot of ground and visited a great series of parks, lodges, and reserves, racking up a respectable group list of 459 bird species seen as well as some nice mammals. There was a lot of rain in the area, but we had to consider ourselves fortunate that the rainiest days seemed to coincide with our long travel days, so it really didn’t cost us too much in the way of birds. My personal trip favorite sighting was our amazing and prolonged encounter with a rare Helmeted Woodpecker! Others of note included extreme close-ups of Spot-winged Wood-Quail, a surprise Sungrebe, multiple White-necked Hawks, Long-trained Nightjar, 31 species of antbirds, scope views of Variegated Antpitta, a point-blank Spotted Bamboowren, tons of colorful hummers and tanagers, TWO Maned Wolves at the same time, and Giant Anteater. This report is a bit light on text and a bit heavy of photos, mainly due to my insane schedule lately where I have hardly had any time at home, but all photos are from the tour. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 The trip started in the city of Curitiba. -

Beijing & Yunnan, China, with OBC

Beijing & Yunnan, China, with OBC. An at-a-glance list of 436 species of birds & eight species of mammals recorded. By Jesper Hornskov ® ***this draft 22 Aug 2010*** ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Please note that the following list is best considered a work in progress. It should not be quoted without consulting the author . Based mostly on my own field notes, this brief write-up covers the birds & mammals noted by C Clifford (until 27 March), C Dietzen, P Drake-Brockman, R East, W Grossi, E Patterson, P Post, W v d Schot, N Zalinge & myself during the 15 March – 3 April 2010 OBC Fundraiser trip to Beijing’s Botanical Garden, and Lijiang, Gaoligongshan, Tengchong, the Yingjiang area & Ruili. We recorded 436 species of birds and eight species of mammals on the 'main tour', very similar totals to those of a private tour in 2008 & the 2009 OBC Fundraiser. An additional 24 species were noted when eight of us covered Beijing's Wild Duck Lake on 4 th - to make it easier for future participants to decide if it might be worth their while to extend their visit by a day or two these are mentioned in the list but are not included in the total species tally - and quite a few more, notably Long-billed Plover Charadrius placidus , and Tristram’s Emberiza tristrami & Yellow-browed Buntings E. chrysophrys , were found during 'non-scheduled' excursions before and after the trip. Beijing's winter returned with a vengeance in the run-up to the trip, with thick snow in the mountains preventing access to the Ibisbill site on 14 March.