President Truman's Recognition of Israel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kırmızı Çızgı

JAMESBARR KIRMIZI ÇIZGI• • Paylaşılamayan Toprakların Yakın Tarihi İngilizceden Çeviren: EKİN CAN GÖKSOY PEGASUS YAYıNLARı Britanya ve Fransa Arasında 20. Yüzyıla Yön Veren Güç Oyunları 1916'da, İngilizlerin Kut'ül Amare'de bozguna uğramasının hemen ardından iki adam, öngörü lü bir politikacı olan Sir Mark Sykes ile hınç dolu bir diplomat olan François Georges- Picot Orta Doğu'yu paylaşma planlarını görüşmek üzere gizlice buluştu. İki adamın vardığı anlaşma bir yandan İngiliz-Fransız Dostluk Antlaşması'nı tehlikeye sokacak gerilimleri hafifletmeyi amaç larken bir yandan da Akdeniz'den İran sınırına uzanan bir hat çiziyordu. Bu keskin hattın ku zeyindeki bölge Fransaya, güneyindeki bölge ise Britanya'ya gidecekti. İngiltere'nin Filistin, Mavera-i Ürdün ve Irak'taki mandaları ile Fran sanın Lübnan ve Suriye'deki mandaları iki büyük güç arasında bir huzursuzluk doğuracaktı. Gele cek otuz yıla damgasını vuracak bu sıkıntı, Orta Doğu'nun da onarılmaz bir biçimde şekillenme sine neden olacaktı. T. E. Lawrence, Winston Churchill ve Charles de Gaulle gibi siyasetçiler, diplomatlar, ajanlar ve askerlerden oluşan yıldız kadrosuyla Kırmızı Çizgi bizlere İngiliz ve Fransızların Orta Doğu'yu yönettiği, kısa ama -çok önemli bir dönemin hikayesini canlı bir biçimde anlatıyor. Kitap aynı zamanda bu iki güç arasındaki eski çekişmenin bugün bizim için çok daha tanıdık olan, Araplar ile Yahudiler arasındaki çatışmayı nasıl ateşledi ğini ve en nihayetinde 1941 'de İngilizler ile Fran sızlar, 1948'de de Araplar ile Yahudiler arasında ki savaşlara nasıl vesile olduğunu net bir şekilde ortaya koyuyor. James Barr'ın, Orta Doğu'nun kaderine yön veren ve bugün bölgenin adeta gayya kuyusu na dönüşmesinde hatırı sayılır bir rol oynayan İngilizler ile Fransızlar arasındaki gizli kapaklı mücadeleyi kaleme aldığı Kırmızı Çizgi, Orta Doğu'nun yakın tarihine ilgi duyan herkesin mutlaka okuması gereken bir kitap. -

Your Shabbat Edition • August 21, 2020

YOUR SHABBAT EDITION • AUGUST 21, 2020 Stories for you to savor over Shabbat and through the weekend, in printable format. Sign up at forward.com/shabbat. GET THE LATEST AT FORWARD.COM 1 GET THE LATEST AT FORWARD.COM News Colleges express outrage about anti- Semitism— but fail to report it as a crime By Aiden Pink Binghamton University in upstate New York is known as including antisemitic vandalism at brand-name schools one of the top colleges for Jewish life in the United known for vibrant Jewish communities like Harvard, States. A quarter of the student population identifies as Princeton, MIT, UCLA and the University of Maryland — Jewish. Kosher food is on the meal plan. There are five were left out of the federal filings. historically-Jewish Greek chapters and a Jewish a Universities are required to annually report crimes on capella group, Kaskeset. their campuses under the Clery Act, a 1990 law named When a swastika was drawn on a bathroom stall in for 19-year-old Jeanne Clery, who was raped and Binghamton’s Bartle Library in March 2017, the murdered in her dorm room at Lehigh University in administration was quick to condemn it. In a statement Pennsylvania. But reporting on murders is far more co-signed by the Hillel director, the school’s vice straightforward, it turns out, than counting bias crimes president of student affairs said bluntly: “Binghamton like the one in the Binghamton bathroom. University does not tolerate hate crimes, and we take all instances of this type of action very seriously.” Many universities interpret the guidelines as narrowly as possible, leaving out antisemitic vandalism that But when Binghamton, which is part of the State would likely be categorized as hate crimes if they University of New York system, filed its mandatory happened off-campus. -

Copyright by Benjamin Jonah Koch 2011

Copyright by Benjamin Jonah Koch 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Benjamin Jonah Koch Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Watchmen in the Night: The House Judiciary Committee’s Impeachment Inquiry of Richard Nixon Committee: David Oshinsky, Supervisor H.W. Brands Dagmar Hamilton Mark Lawrence Michael Stoff Watchmen in the Night: The House Judiciary Committee’s Impeachment Inquiry of Richard Nixon by Benjamin Jonah Koch, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Dedication To my grandparents For their love and support Acknowledgements I owe an immense debt of gratitude to my dissertation supervisor, David Oshinsky. When I arrived in graduate school, I did not know what it meant to be a historian and a writer. Working with him, especially in the development of this manuscript, I have come to understand my strengths and weaknesses, and he has made me a better historian. Thank you. The members of my dissertation committee have each aided me in different ways. Michael Stoff’s introductory historiography seminar helped me realize exactly what I had gotten myself into my first year of graduate school—and made it painless. I always enjoyed Mark Lawrence’s classes and his teaching style, and he was extraordinarily supportive during the writing of my master’s thesis, as well as my qualifying exams. I workshopped the first two chapters of my dissertation in Bill Brands’s writing seminar, where I learned precisely what to do and not to do. -

Converted but Not Quite Accepted Meetings with the Student Rabbi Were Disappoint- Ing and Almost Discouraging

to listen to people more deeply, rather than put them shock. Not only were there many bright children now off with words. Probably all those years of fencing in my classes, but also lots of wealthy, cultured class- and fighting with professors to learn and get the job mates. I suddenly became the "country bumpkin." I done carried over onto the job at first. Almost all first was the W.A.S.P. minority and read a library book all year teachers have to learn to co-operate and compro- alone in school on the Jewish holidays. mise much more so than they did in their college days. Eventually I became a part of the culture. Families I began to really like the man, and as our personal as well as my friends included me at their Seders, conferences toward conversion progressed, I develop- and Bar Mitzvahs were the major social event for ed a new respect for his type of restless, inquiring three years running. I became more familiar with scholarship. He was most generous in loaning me any temple procedure than I had ever been with any book in his personal library, something other rabbis church. With this background I entered my first might hesitate to do, especially with books they marriage with a Jewish boy from my high school. treasure. The idea of my conversion occurred to me, and I Finally on March 21, 1975 I stood in front of the remember remarking that "Maybe I could . ." open Ark and converted to Judaism. I'll admit to (being a rather tentative person at that time); I was being so nervous that I stumbled over the words of told that that would be a crazy thing to do. -

Proceedings of the Fifty-Sixth Annual Meeting

PROCEEDINGS OF THE FIFTY-SIXTH ANNUAL MEETING JAMES TATE, JR., SECRETARY At the invitation of the Montana State University and the Sacajawea Audubon Society, the 56th annual meeting of The Wilson Ornithological Society was held jointly with The Cooper Ornithological Society. The site of the joint meeting was the modern and com- fortable campus of Montana State University in Bozeman, Montana. This second joint meeting of the 2 societies was conducted from 12 through 15 June 1975. The Executive Council of The Wilson Ornithological Society held 2 meetings in a conference room at the Hedges North Residence Hall. Business meetings of The Wilson Society were held in the meeting room in Johnson Hall. These proceedings detail the decisions made, awards presented, papers heard, friends well met, and presentations enjoyed in the beautiful Gal- latin Valley of Montana. A pleasant reception for early registrants was hosted Wednesday evening by the Saca- jawea Audubon Society while the Executive Council of The Wilson Society and the Board of Directors of The Cooper Ornithological Society held their separate meetings. On Thursday morning the societies were welcomed in their General Session by Carl W. IMcIntosh, President of Montana State University. A full day of scientific papers fol- lowed. An evening film, Land of Shining Mountains, was presented by Louis M. Moos, photographer and lecturer. Well-organized birding trips were held to nearby localities for the early risers on Friday and Saturday mornings. Fridays’ scientific program consisted of a Symposium on Avian Habitats organized by Douglas James. On Friday evening a full schedule of films and slide shows was available to registrants and guests: (1) The Effects of Airborne Contaminants on Vertebrate Animals, slides by Robert A. -

Korff, Baruch (1)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 19, folder “Korff, Baruch (1)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 19 of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library TnE WHITE HOUSE . WASHINGTON Some items in this folder were not digitized because it contains copyrighted materials. Please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library for access to these materials. The News- Once Over Lightly --NON-·PROF/TN-ON·PARTI-MN WE, THE PEOPLt! At Home Africa-In the three-way civil war which has wracked Angola since Portugal granted it independence, national VNITED STATES CITIZENS CONGRESS troops captured 20 Soviet soldiers. They claimed they Washington-Nelson Rockefeller may quit national were waiting for a Streetcar Named Detente. 1221 CONNECTICUT AVENUE, NORTHWEST • WASHINGTON, D. C. • 20036 politics in 197 6. He believes that it's better to be left than President. Buenos Aires--Women's Lib is taking a beating in ''I am in earnest. -

1988-05-12.Pdf

- - -- - - - ·--- - - - ·- - - -- - -·- - - --------------- - - --~ -D ;5': ("-.I z C• 8 Local News, pages 2-3 ,;.. f- f--· - <r Opinion, page 4 ~ (!) - 0- 0 u Around Town, page 8 ISR,ll~L 7Nll!I' I tn ~, Lf) *..-<<[ *t<• * _J * *U<r * *1-1 * u:: * 0 *O'-C.Of-* f- - * Q:)1-1(1)1--1 *'·I Ct: *..-< [.fJ *t··)I.Z .... *·,.mow *...--11-11-10 * 3 (J)Z * WCJlW JSL Y ENGL/SH--JEW!SH \VEEKLY /.V R.I. AND SOLTHEAST MASS. * t-:1WCI *...--1 (fJ 1-1 * 'T • :::,. *C""·~l---4--00 ,XXV, NUMBER 24 THURSDAY, MAY 12, 1988 35¢ PER COPY * •t··)CC: * CC: ·,-qj_ Dedication Of The Rhode Island Holocaust Memorial Museum by Sandra Silva Survivors of the Holocaust, their The sun did not shine brightly children, other family and commu down on the crowd and only occa nity members, Jewish and Chris sionally peeped through the gray tian clergy and local politicians blue clouds that blanketed the sky. joined together this day for the Fortunately, rain did not fall. How moving and reflective ceremonies. ever, one would feel a few drops of Governor DiPrete spoke for the wetness borne within the soft, cool entire Rhode Island community breezes that blew upon the court when he said, "I can assure you yard. The weather was an adequate that all Rhode Islanders join me in complement to the hushed, sub recognizing this historic occasion. dued atmosphere that prevailed This is a place that belongs to all upon the courtyard. people because in a great sense the No extreme was shown. The pain ultimate victims of the Holocaust of remembering was obvious but were all humanity. -

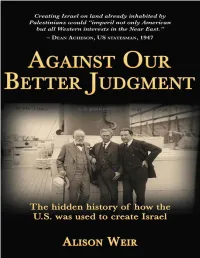

Against Our Better Judgment: the Hidden History of How the U.S. Was

Against Our Better Judgment The hidden history of how the U.S. was used to create Israel ALISON WEIR Copyright © 2014 Alison Weir All rights reserved. DEDICATION To Laila, Sarah, and Peter CONTENTS Aknowledgments Preface Chapter One: How the U.S. “Special Relationship” with Israel came about Chapter Two: The beginnings Chapter Three: Louis Brandeis, Zionism, and the “Parushim” Chapter Four: World War I & the Balfour Declaration Chapter Five: Paris Peace Conference 1919: Zionists defeat calls for self- determination Chapter Six: Forging an “ingathering” of all Jews Chapter Seven: The modern Israel Lobby is born Chapter Eight: Zionist Colonization Efforts in Palestine Chapter Nine: Truman Accedes to Pro-Israel Lobby Chapter Ten: Pro-Israel Pressure on General Assembly Members Chapter Eleven: Massacres and the Conquest of Palestine Chapter Twelve: U.S. front groups for Zionist militarism Chapter Thirteen: Infiltrating displaced person’s camps in Europe to funnel people to Palestine Chapter Fourteen: Palestinian refugees Chapter Fifteen: Zionist influence in the media Chapter Sixteen: Dorothy Thompson, played by Katharine Hepburn & Lauren Bacall Works Cited Further Reading Endnotes ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am extremely grateful to Katy, who plowed through my piles of obscure books and beyond to check it; to Sarah, whose design so enhanced it; to Monica, whose splendid work kept things together; and to the special, encouraging friends (you know who you are) who have made this all possible. Above all, I am profoundly grateful to the authors and editors who have produced superb work on this issue for so many years, many receiving little personal gain despite the excellence and dedication of their labors. -

UMA PEQUENA AMÉRICA NO ORIENTE: Fundamentos Culturais Do Apoio Ao Sionismo Nos Estados Unidos (1936-1948)

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL FLUMINENSE INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS E FILOSOFIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA LUIZ SALGADO NETO UMA PEQUENA AMÉRICA NO ORIENTE: fundamentos culturais do apoio ao sionismo nos Estados Unidos (1936-1948) Niterói 2013 LUIZ SALGADO NETO UMA PEQUENA AMÉRICA NO ORIENTE: fundamentos culturais do apoio ao sionismo nos Estados Unidos (1936-1948) Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação Stricto Sensu em História da Universidade Federal Fluminense, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do Grau de Mestre. Área de concentração: História Social. Orientadora: Professora Doutora Cecília da Silva Azevedo Niterói, 2013 Ficha Catalográfica elaborada pela Biblioteca Central do Gragoatá S164 Salgado Neto, Luiz. Uma pequena América no Oriente: fundamentos culturais do apoio ao sionismo nos Estados Unidos (1936-1948) / Luiz Salgado Neto. – 2013. 289 f. ; il. Orientador: Cecília da Silva Azevedo. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Universidade Federal Fluminense, Instituto de Ciências Humanas e Filosofia, Departamento de História, 2013. Bibliografia: f. 281-289. 1. Palestina. 2. Estados Unidos. 3. Israel. 4. Oriente Médio. I. Azevedo, Cecília da Silva. II. Universidade Federal Fluminense. Instituto de Ciências Humanas e Filosofia. III. Título. CDD 956.9404 LUIZ SALGADO NETO Uma pequena América no Oriente: fundamentos culturais do apoio ao sionismo nos Estados Unidos (1936-1948) Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação Stricto Sensu em História da Universidade Federal Fluminense, como requisito parcial para a obtenção -

Folder 23 Vaad Hahatzala Emergency Committee

Dear Rabbi Kalrnanowitz1 I am pleased to forward here\'1-ith photostatic copies of a report made by your Istnn bul committ~e to the American Embassy, Ankara, Turkey. Very truly yours, J; w. Pehle Executive ·Director Rabbi A. Kalmanowi tz, 'vaad Hahatzala F:mergancy CoL'Uni,, ttee, 132 Naseau Street, New York 7, N. Y. Enclosures. FH:hd ~ 11/25/44 ~ ... IOV 27. Dear Rabbi Kalmanowitzi Receipt ia acknowledged of your letter of November 19, 1944, enclosing a oopy of your financial statement for the period of c1.almary 1 to Oetober 31, 1944. Vecy\ truly yours, J. W~ Pehle Executive Director Rabbi A. Kalmanowitz, Vaad Hahatzala Emergency Committee, i32 Nassau Street, New York 7, N. Y. /(5:Z: FH :hd ll/';.4/44 132 NASSAU STREET (ROOM 819) NEW YORK 7, N. Y. PHONE RECTOR 2·4235 Nov • 19 , 1944. Honorable John w. Pehle, Executive Director war Hefugee Board Treasury Building washington, n.o. ., Honorable Sirs- We enclose a copy of our financial statement which 'covers the period of January 1st to October 31st, 1944. xou are intimately aware of all the effort, blood, sweat and tears that is contained in the vaad Hahatzala work. ~From the very inception of the war Refug~e Board, the·vaad Hahatzala has stood in the vanguard of the rescue work, and such rescue measures as procurement of passports,, crossing refugees from one b·order to another, the ransom of ma~__ l_lE):LI!._bx J;he_eneuw, were init111ted by the vaad Hahatzal_a and carried through by its committees in. the. neutral lands. -

ABSTRACT Refugees in Times of Reelection: an Analysis of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman's Responses to Jewish R

ABSTRACT Refugees in Times of Reelection: An Analysis of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman’s Responses to Jewish Refugees During and After World War II. Anabel Burke Director: Dr. Lauren Poor, Ph.D. Many individuals hold a false notion that America is a safe haven for refugees, but a closer look at the refugee crisis surrounding World War II (1930-1948) tells a different story; Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) and Harry S. Truman faced the difficult decision of if they should help Jewish refugees, and if so, how. In this thesis I argue that presidents’ actions concerning refugees are tempered by political concerns and driven by a xenophobic America, and that for a president to act humanitarianly and openly in refugees’ best interest that they are usually not facing reelection and are in a relatively safe political position. By examining the political correspondence of both presidents, I show that refugees fare best when they seek aid and admittance to the United States under a second-term president, and the examples of FDR and Truman help to shed a light on the more recent Syrian refugee crisis and former President Obama’s motivations and dealings with those clamoring at America’s gates. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS: _______________________________________________ Dr. Lauren Poor, Department of History APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM: ________________________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Corey, Director DATE: ________________________________ REFUGEES IN TIMES OF REELECTION: AN ANALYSIS OF FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT AND HARRY S. TRUMAN’S RESPONSES TO JEWISH REFUGEES DURING AND AFTER WORLD WAR II. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Baylor University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Honors Program By Anabel Burke Waco, Texas May 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements . -

The U.S. Recognition of Israel: a Bureaucratic Politics Model Analysis

The U.S. Recognition of Israel: A Bureaucratic Politics Model Analysis Nilay Saiya Political Science Villanova University The outsider believes a Presidential order is consistently followed out. Nonsense. I have to spend considerable time seeing that it is carried out and in the spirit the President intended. Inevitably, in the nature of bureaucracy, departments become pressure groups for a point of view. If the President decides against them, they are convinced some evil influence worked on the President: if only he knew all the facts, he would have decided their way. –Richard Nixon1 The bureaucratic politics model holds that each bureaucracy in the federal government has institutional beliefs it is seeking to maximize. The competition is based upon relative power and influence. I seek to examine how these competing bureaucracies helped influence U.S. foreign policy toward Israel during the Truman administration. Specifically I hope to address the following question: How does the bureaucratic politics model explain the United States decision to recognize Israel? According to bureaucratic politics theory, decisions are determined not by rational choice or chief actors but through a give-and-take bargaining process conducted by various parties of the government. Rather than unitary actors, this model maintains that governmental decisions are the result of individuals or organizations vying for position and power. Therefore, the outcomes are a direct result of bureaucratic competition. Prominent scholars of the bureaucratic politics model