The Image of the Real World and the World Beyond in the Slovene Folk Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Bus Around the Julian Alps

2019 BY BUS AROUND THE JULIAN ALPS BLED BOHINJ BRDA THE SOČA VALLEY GORJE KRANJSKA GORA JESENICE rAdovljicA žirovnicA 1 2 INTRO 7 BLED, RADOVLJICA, ŽIROVNICA 8 1 CHARMING VILLAGE CENTRES 10 2 BEES, HONEY AND BEEKEEPERS 14 3 COUNTRYSIDE STORIES 18 4 PANORAMIC ROAD TO TRŽIČ 20 BLED 22 5 BLED SHUTTLE BUS – BLUE LINE 24 6 BLED SHUTTLE BUS – GREEN LINE 26 BOHINJ 28 7 FROM THE VALLEY TO THE MOUNTAINS 30 8 CAR-FREE BOHINJ LAKE 32 9 FOR BOHINJ IN BLOOM 34 10 PARK AND RIDE 36 11 GOING TO SORIŠKA PLANINA TO ENJOY THE VIEW 38 12 HOP-ON HOP-OFF POKLJUKA 40 13 THE SAVICA WATERFALL 42 BRDA 44 14 BRDA 46 THE SOČA VALLEY 48 15 HOP-ON HOP-OFF KOBARID – RED LINE 50 16 HOP-ON HOP-OFF KOBARID – ORANGE LINE 52 17 HOP-ON HOP-OFF KOBARID – GREEN LINE 54 18 HOP-ON HOP-OFF KOBARID – PURPLE LINE 56 19 HOP-ON HOP-OFF KOBARID – BLUE LINE 58 20 THE TOLMINKA RIVER GORGE 62 21 JAVORCA, MEMORIAL CHURCH IN THE TOLMINKA RIVER VALLEY 64 22 OVER PREDEL 66 23 OVER VRŠIČ 68 KRANJSKA GORA 72 24 KRANJSKA GORA 74 Period during which transport is provided Price of tickets Bicycle transportation Guided tours 3 I 4 ALPS A JULIAN Julian Alps Triglav National Park 5 6 SLOVEniA The Julian Alps and the Triglav National Park are protected by the UNESCO Man and the Biosphere Programme because the Julian Alps are a treasury of natural and cultural richness. The Julian Alps community is now more interconnected than ever before and we are creating a new sustainable future of green tourism as the opportunity for preserving cultural and natural assets of this fragile environment, where the balance between biodiversity and lifestyle has been preserved by our ancestors for centuries. -

Križarska Vojska Proti Kobaridcem 1331

ZGODOVINSKI ČASOPIS 38 . 1984 . 1—2 . 49-55 49 Ivo Juvančič KRIŽARSKA VOJSKA PROTI KOBARIDCEM 1331 Križarska vojska? Da, tako stoji zapisano v dokumentu. Proti Kobaridu? Da." Frančiškan Franciscus de Clugia (Francesco di Chioggia), inkvizitor zoper heretično izprijenost v Benečiji in Furlaniji je ugotovil določene zmote v oglejski diecezi in je v »slovesni pridigi« v Čedadu oznanil križarsko,vojno in pozval vernike, naj po magajo.1 Nekateri prelati, duhovniki in redovniki so mu bili v pomoč. Sli so, me brez osebne nevarnosti, vse do kraja Kobarida, v isti škofiji, kjer so med gorami nešteti Slovani častili neko drevo in studenec, ki je bil pri koreninah drevesa, kot boga, izkazujoč ustvarjeni stvari češčenje, ki se po veri dolguje stvarniku«.2 Drevo so s pomočjo omenjenih dali popolnoma izruvati, studenec pa s kamni zasuti. Li stino, v kateri je vse to popisano in ki jè tudi edini vir za to križarsko vojno, je izdal 16. avgusta 1331 v Vidmu (Udine) sam inkvizitor Franciscus3 v pohvalo in priznanje udeležencu pohoda, oglejskemu kanoniku Ulriku Bojanu iz Čedada, ki je bil tedaj župnik šmartinske fare pri Kranju. Vladimir Leveč jo je v začetku tega stoletja našel v čedajskem kapiteljskem arhivu, v zbirki plemiške družine Boiano (Boiani).4 Simon Rutar je omenil del tega dogodka v Zgodovinskih črticah o Bovškem, objavljenih v Soči.5 Zveza je razumljiva, ker so Bovčani v veliki večini s Kobaridci, zlasti Kotarji tja do Breginja in po Soči še do Volč imeli istega zemljiškega gospoda v Rožacu. Rutar je napisal, da je krščanstvo, ki so ga širili oglejski patriarhi s po močjo čedajske duhovščine, »po naših gorah jako polagoma napredovalo. -

World Regional Geography Book Series

World Regional Geography Book Series Series Editor E. F. J. De Mulder DANS, NARCIS, Utrecht, The Netherlands What does Finland mean to a Finn, Sichuan to a Sichuanian, and California to a Californian? How are physical and human geographical factors reflected in their present-day inhabitants? And how are these factors interrelated? How does history, culture, socio-economy, language and demography impact and characterize and identify an average person in such regions today? How does that determine her or his well-being, behaviour, ambitions and perspectives for the future? These are the type of questions that are central to The World Regional Geography Book Series, where physically and socially coherent regions are being characterized by their roots and future perspectives described through a wide variety of scientific disciplines. The Book Series presents a dynamic overall and in-depth picture of specific regions and their people. In times of globalization renewed interest emerges for the region as an entity, its people, its landscapes and their roots. Books in this Series will also provide insight in how people from different regions in the world will anticipate on and adapt to global challenges as climate change and to supra-regional mitigation measures. This, in turn, will contribute to the ambitions of the International Year of Global Understanding to link the local with the global, to be proclaimed by the United Nations as a UN-Year for 2016, as initiated by the International Geographical Union. Submissions to the Book Series are also invited on the theme ‘The Geography of…’, with a relevant subtitle of the authors/editors choice. -

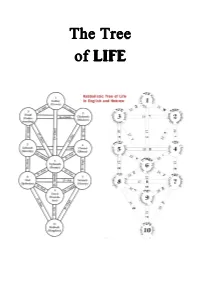

The Tree of LIFE

The Tree of LIFE ~ 2 ~ ~ 3 ~ ~ 4 ~ Trees of Life. From the highest antiquity trees were connected with the gods and mystical forces in nature. Every nation had its sacred tree, with its peculiar characteristics and attributes based on natural, and also occasionally on occult properties, as expounded in the esoteric teachings. Thus the peepul or Âshvattha of India, the abode of Pitris (elementals in fact) of a lower order, became the Bo-tree or ficus religiosa of the Buddhists the world over, since Gautama Buddha reached the highest knowledge and Nirvâna under such a tree. The ash tree, Yggdrasil, is the world-tree of the Norsemen or Scandinavians. The banyan tree is the symbol of spirit and matter, descending to the earth, striking root, and then re-ascending heavenward again. The triple- leaved palâsa is a symbol of the triple essence in the Universe - Spirit, Soul, Matter. The dark cypress was the world-tree of Mexico, and is now with the Christians and Mahomedans the emblem of death, of peace and rest. The fir was held sacred in Egypt, and its cone was carried in religious processions, though now it has almost disappeared from the land of the mummies; so also was the sycamore, the tamarisk, the palm and the vine. The sycamore was the Tree of Life in Egypt, and also in Assyria. It was sacred to Hathor at Heliopolis; and is now sacred in the same place to the Virgin Mary. Its juice was precious by virtue of its occult powers, as the Soma is with Brahmans, and Haoma with the Parsis. -

The Heart of Slovenia

source: hidden europe 38 (winter 2012/2013) text and photos © 2012 Jonathan Knott Feature www.hiddeneurope.co.uk The heart of Slovenia by Jonathan Knott This is the story of a walk. A walk through was told to wrap up well, and I’m glad I did. 10 landscape, language and history into the The bright sunlight belies a bitter wind. heart, even into the very soul, of Slovenia. I It may be a national holiday, but plenty of Guest contributor Jonathan Knott reports on Slovenians are up early today. So the streets of how Slovenians mark the anniversary of the Žirovnica are already busy. death of their national poet France Prešeren. The eighth day of February is a holiday in Slovenia, commemorating the death of France Prešeren. Each year on this day, people from across the country gather for a ceremony at Prešeren’s birthplace in Vrba, one of a cluster of Above: Walkers cross open land between villages of the Kašarija, with Slovenia’s highest mountain, Triglav, villages that are collectively dubbed Kašarija. The dominating the skyline (photo by Polona Kus). entire population of these communities amounts hidden europe 38 winter 2012 / 2013 Sunrise now gilds the threefold peaks unbowed Of Carniola’s grey and snowbound height. From France Prešeren, ‘Baptism at the Savica’ (1935) to only about 4000 but this small municipality attire appropriate to his legal profession, but his — officially called Žirovnica, after the biggest flowing dark locks and unfocused, deep gaze of the ten villages — has long punched above its are those of the archetypal Romantic poet. -

Comparative Literature in Slovenia

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 2 (2000) Issue 4 Article 11 Comparative Literature in Slovenia Kristof Jacek Kozak University of Alberta Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Kozak, Kristof Jacek. "Comparative Literature in Slovenia." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 2.4 (2000): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1094> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 2344 times as of 11/ 07/19. -

Bakalářská Práce

UNIVERZITA KARLOVA V PRAZE Fakulta humanitních studií BAKALÁŘSKÁ PRÁCE Praha 2007 Taťána Marčićová UNIVERZITA KARLOVA V PRAZE Fakulta humanitních studií STOPY A REFLEXE LIDOVÉ VÍRY V ÚSTNÍ TRADICI ČERNOHORCŮ (V SOUVISLOSTI SE SLOVANSKÝM NÁBOŽENSKÝM SYSTÉMEM). PŘÍPAD ZDUCHAČE. Student: Taťána Marčićová Vedoucí bakalářské práce : Dott. Giuseppe Maiello, PhD. Studijní obor: Studium humanitní vzdělanosti 2 Děkuji Dott. Giuseppe Maiellovi, PhD. za cenné rady a podněty pro tuto práci a Vukovi Begovićovi a jeho rodině za poskytnutou pomoc a zázemí, které jsem potřebovala během průzkumné práce v Černé Hoře. 3 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci vypracoval/a samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a souhlasím s jejím eventuálním zveřejněním v tištěné nebo elektronické podobě. V Praze dne 29. 6. 2007 ....................................... podpis 4 OBSAH 1. ÚVOD........................................................................................................................7 2. METODIKA PRÁCE....................................................................................................10 3. HLAVNÍ HISTORICKÉ PRAMENY................................................................................11 3. 1 HISTORICKÉ PRAMENY TÝKAJÍCÍ SE POLABSKÝCH SLOVANŮ......................................................................................................11 3. 2 HISTORICKÉ PRAMENY TÝKAJÍCÍ SE VÝCHODNÍCH SLOVANŮ......................................................................................................12 3. 3 HISTORICKÉ PRAMENY TÝKAJÍCÍ SE -

(1389) and the Munich Agreement (1938) As Political Myths

Department of Political and Economic Studies Faculty of Social Sciences University of Helsinki The Battle Backwards A Comparative Study of the Battle of Kosovo Polje (1389) and the Munich Agreement (1938) as Political Myths Brendan Humphreys ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Helsinki, for public examination in hall XII, University main building, Fabianinkatu 33, on 13 December 2013, at noon. Helsinki 2013 Publications of the Department of Political and Economic Studies 12 (2013) Political History © Brendan Humphreys Cover: Riikka Hyypiä Distribution and Sales: Unigrafia Bookstore http://kirjakauppa.unigrafia.fi/ [email protected] PL 4 (Vuorikatu 3 A) 00014 Helsingin yliopisto ISSN-L 2243-3635 ISSN 2243-3635 (Print) ISSN 2243-3643 (Online) ISBN 978-952-10-9084-4 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-9085-1 (PDF) Unigrafia, Helsinki 2013 We continue the battle We continue it backwards Vasko Popa, Worriors of the Field of the Blackbird A whole volume could well be written on the myths of modern man, on the mythologies camouflaged in the plays that he enjoys, in the books that he reads. The cinema, that “dream factory” takes over and employs countless mythical motifs – the fight between hero and monster, initiatory combats and ordeals, paradigmatic figures and images (the maiden, the hero, the paradisiacal landscape, hell and do on). Even reading includes a mythological function, only because it replaces the recitation of myths in archaic societies and the oral literature that still lives in the rural communities of Europe, but particularly because, through reading, the modern man succeeds in obtaining an ‘escape from time’ comparable to the ‘emergence from time’ effected by myths. -

Sources of Mythology: National and International

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY & EBERHARD KARLS UNIVERSITY, TÜBINGEN SEVENTH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY SOURCES OF MYTHOLOGY: NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL MYTHS PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS May 15-17, 2013 Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany Conference Venue: Alte Aula Münzgasse 30 72070, Tübingen PROGRAM WEDNESDAY, MAY 15 08:45 – 09:20 PARTICIPANTS REGISTRATION 09:20 – 09:40 OPENING ADDRESSES KLAUS ANTONI Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany JÜRGEN LEONHARDT Dean, Faculty of Humanities, Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany 09:40 – 10:30 KEYNOTE LECTURE MICHAEL WITZEL Harvard University, USA MARCHING EAST, WITH A DETOUR: THE CASES OF JIMMU, VIDEGHA MATHAVA, AND MOSES WEDNESDAY MORNING SESSION CHAIR: BORIS OGUIBÉNINE GENERAL COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY AND METHODOLOGY 10:30 – 11:00 YURI BEREZKIN Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, Saint Petersburg, Russia UNNOTICED EURASIAN BORROWINGS IN PERUVIAN FOLKLORE 11:00 – 11:30 EMILY LYLE University of Edinburgh, UK THE CORRESPONDENCES BETWEEN INDO-EUROPEAN AND CHINESE COSMOLOGIES WHEN THE INDO-EUROPEAN SCHEME (UNLIKE THE CHINESE ONE) IS SEEN AS PRIVILEGING DARKNESS OVER LIGHT 11:30 – 12:00 Coffee Break 12:00 – 12:30 PÁDRAIG MAC CARRON RALPH KENNA Coventry University, UK SOCIAL-NETWORK ANALYSIS OF MYTHOLOGICAL NARRATIVES 2 NATIONAL MYTHS: NEAR EAST 12:30 – 13:00 VLADIMIR V. EMELIANOV St. Petersburg State University, Russia FOUR STORIES OF THE FLOOD IN SUMERIAN LITERARY TRADITION 13:00 – 14:30 Lunch Break WEDNESDAY AFTERNOON SESSION CHAIR: YURI BEREZKIN NATIONAL MYTHS: HUNGARY AND ROMANIA 14:30 – 15:00 ANA R. CHELARIU New Jersey, USA METAPHORS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF MYTHICAL LANGUAGE - WITH EXAMPLES FROM ROMANIAN MYTHOLOGY 15:00 – 15:30 SAROLTA TATÁR Peter Pazmany Catholic University of Hungary A PECHENEG LEGEND FROM HUNGARY 15:30 – 16:00 MARIA MAGDOLNA TATÁR Oslo, Norway THE MAGIC COACHMAN IN HUNGARIAN TRADITION 16:00 – 16:30 Coffee Break NATIONAL MYTHS: AUSTRONESIA 16:30 – 17:00 MARIA V. -

Madness in Greek Thought and Custom

he niversi of Mic t u ty higan Madne ss in G re e k Tho ught and C usto m AGNES CARR VAU GH AN A ssis tan t Profeuor of Greek in Wells College A D IS S E RT A T IO N S IN AR AL FU LFILLME N U D P T m M R BME “ “ FO ITT TI Q IN U NIVERSIT"OF MICH IGA N B A M LT I O RE MPA N " 1 . H . FU RST C O 1 9 1 9 PREFACE Before presenting the material of this di ssertation I wish to take the opportunity to express my deep appreciation of the assistance and encouragement given me in my work by the G an d M reek Latin faculties of the University of ichigan and of B C ryn Mawr ollege . I wish to thank especially P rofessor Campbell Bonner of th e University of Michigan for his direction and supervision dur ing the entire period of preparation of this dissertation and to the express my gratitude to Professo r Francis W. Kelsey of University of Michigan for his interest in the work and for his t many valuable sugges ions . M f G m o I . o th e am also indebted to Mr . F o re of depart ent Classical Philology of Columbia University for his courtesy in extending to me th e privileges of the Columbia Library . N v m 1 91 9. o e ber , TABLE OF CONTENT S H n u t n C AP R I. -

Stare Vatre Opet Plamte Srbinda

EEKC “SFERA” STARE VATRE OPET PLAMTE TM SRBINDA DOWNLOADED FROM: WWW.SRBINDA.COM Izdavač / Published by: Ekološko-etnološki kulturni centar “Sfera” / Center Of Ecology, Ethnology and Culture “Sphere” Novi Sad, SERBIA, 2012 COPyRIght © 2012 by gORAN POlEtAN DESIgN & lAyOUt : SRBINDA All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. ISBN : 978-86-85539-17-6 CIP – Каталогизација у публикацији Библиотека Матицe српске, Нови Сад 821.163.41-14 ПОЛЕТАН, Горан, Stare vatre opet plamte / goran Poletan. – Novi Sad : Ekološko-etnološki kulturni centar ‘’Sfera’’, 2012. – 106 str. Način dostupa (URl) : http: //www.srbinda.com/. – str. 4- 6 : Predgovor / Aleksandra Marinković-Obrovski. Beleška o autoru: str. [107]. ISBN 978-86-85539-17-6 COBISS.SR-ID 274828295 PREDGOVOR Poruke predaka Stara vera Srba, ona u koju su verovali pre primanja hrišćanstva i koja je proisticala iz najdublje narodne prirode, većim delom je pred- stavljala religijski sistem usmeren ka poštovanju kulta predaka. To u isto vreme znači da su drevni Srbi ovaj kult na različite načine utkali u sva- kodnevni život, potkom koja je bila toliko snažna da je, pokazalo se, uspela da prebrodi i potonju promenu vere. Primanjem hrišćanstva, kult predaka nije izgubio na snazi i ne samo da je nastavio da postoji nego se u gotovo neizmenjenom obliku sačuvao do naših dana, u narodnim običajima kojih se često sa setom prisećamo prizivajući slike iz detin- jstva. Ko još ne pamti badnjedansko pijukanje oko kuće i posnu večeru na slami, ili priče o seoskoj svadbi kada je mlada ljubila ognjište ili, opet, sećanja na klanje petla na temelju nove kuće? Sve su to prežici kulta predaka naročito poštovanog u one dane kada se verovalo da su preci sa nama, tu, oko nas, da nas prate, čuvaju i poučavaju. -

A Survey of Slovenian Women Fairy Tale Writers

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 15 (2013) Issue 1 Article 3 A Survey of Slovenian Women Fairy Tale Writers Milena Mileva Blazić University of Ljubljana Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Other English Language and Literature Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Blazić, Milena Mileva "A Survey of Slovenian Women Fairy Tale Writers." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 15.1 (2013): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.2064> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field.