IDENTITY ARTIFACTS and CULTURAL CRUMBS: an ANALYSIS of the ART MUSIC of JOHN DANGERFIELD COOPER by Marcus Alonzo Simmons Submitt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Royal Umd 0117E 18974.Pdf (465.4Kb)

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: SELECTED WORKS OF COMPOSERS ASSOCIATED WITH HOWARD UNIVERSITY Guericke Christopher Royal, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Chris Gekker School of Music Throughout its over 100 year history, Howard University has produced and attracted many talented composers of many musical genres. Limiting this project to any one genre or focus would have lessened the overall impact of the music they created and the inspiration that has been a lauded part of the institution. The project will demonstrate the various harmonic, melodic, rhythmic and emotional contributions of the selected composers through interpretation of their music on the trumpet. Composers have been connected to the university in three general ways: as students, alumni and faculty; as commissioned artists; and through the performance of their works by notable performers associated with Howard. The pieces selected for this project exemplify a wide range of musical expressions and compositional techniques, and hopefully have been presented in a way that allows the emotional impact of each piece to resonate in a unique fashion. The selected works tended to fall into the categories of A. Trumpet and Brass Works B. Spirituals/ Meditational/ Religious Works C. Popular and Jazz Pieces D. Organ or other Instrumental Works E. Works of Historical Reference or Significance In some cases, certain pieces may be categorized across multiple categories (e.g. an organ piece based on religious material). As this was also a recording project, great care was taken during the recording process to capture as much emotional content as possible through stereo microphone techniques and the use of high quality equipment. -

LCSH Section L

L (The sound) Formal languages La Boderie family (Not Subd Geog) [P235.5] Machine theory UF Boderie family BT Consonants L1 algebras La Bonte Creek (Wyo.) Phonetics UF Algebras, L1 UF LaBonte Creek (Wyo.) L.17 (Transport plane) BT Harmonic analysis BT Rivers—Wyoming USE Scylla (Transport plane) Locally compact groups La Bonte Station (Wyo.) L-29 (Training plane) L2TP (Computer network protocol) UF Camp Marshall (Wyo.) USE Delfin (Training plane) [TK5105.572] Labonte Station (Wyo.) L-98 (Whale) UF Layer 2 Tunneling Protocol (Computer network BT Pony express stations—Wyoming USE Luna (Whale) protocol) Stagecoach stations—Wyoming L. A. Franco (Fictitious character) BT Computer network protocols La Borde Site (France) USE Franco, L. A. (Fictitious character) L98 (Whale) USE Borde Site (France) L.A.K. Reservoir (Wyo.) USE Luna (Whale) La Bourdonnaye family (Not Subd Geog) USE LAK Reservoir (Wyo.) LA 1 (La.) La Braña Region (Spain) L.A. Noire (Game) USE Louisiana Highway 1 (La.) USE Braña Region (Spain) UF Los Angeles Noire (Game) La-5 (Fighter plane) La Branche, Bayou (La.) BT Video games USE Lavochkin La-5 (Fighter plane) UF Bayou La Branche (La.) L.C.C. (Life cycle costing) La-7 (Fighter plane) Bayou Labranche (La.) USE Life cycle costing USE Lavochkin La-7 (Fighter plane) Labranche, Bayou (La.) L.C. Smith shotgun (Not Subd Geog) La Albarrada, Battle of, Chile, 1631 BT Bayous—Louisiana UF Smith shotgun USE Albarrada, Battle of, Chile, 1631 La Brea Avenue (Los Angeles, Calif.) BT Shotguns La Albufereta de Alicante Site (Spain) This heading is not valid for use as a geographic L Class (Destroyers : 1939-1948) (Not Subd Geog) USE Albufereta de Alicante Site (Spain) subdivision. -

University" Microfilms International 300 N

The music of Cuthbert Hely in Cambridge, Fitzwilliam music ms. 689 Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Cockburn, Brian, 1963- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 06:38:47 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/276717 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. -

![1 [27] Ficvaldivia 2 [27] Ficvaldivia 3 [27] Ficvaldivia 4 [27] Ficvaldivia 5](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7781/1-27-ficvaldivia-2-27-ficvaldivia-3-27-ficvaldivia-4-27-ficvaldivia-5-317781.webp)

1 [27] Ficvaldivia 2 [27] Ficvaldivia 3 [27] Ficvaldivia 4 [27] Ficvaldivia 5

[27] FICVALDIVIA 1 [27] FICVALDIVIA 2 [27] FICVALDIVIA 3 [27] FICVALDIVIA 4 [27] FICVALDIVIA 5 [27] FICVALDIVIA Palabras6 9 Words FILMES DE INAUGURACIÓN Filmes de inauguración 26 Opening films Y CLAUSURA OPENING AND CLOSING Filmes de clausura 28 FEATURES P. 25 Closing films Cortometraje de Ceremonia de Premiación 30 Awards Ceremony Short Film JURADO Y ASESORES 33 JURY AND ADVISORS P.33 EN COMPETENCIA Selección Oficial Largometraje Internacional 45 IN COMPETITION Official International Feature Selection P. 44 Selección Oficial Largometraje Chileno 59 Official Chilean Feature Selection Selección Oficial Largometraje Juvenil 67 Internacional Official International Youth Feature Selection Selección Oficial Cortometraje 75 Latinoamericano Official Latin-American Short Film Selection Selección Oficial Cortometraje Infantil 89 Latinoamericano Official Latin-American Children’s Short Film Selection Selección Oficial Cine Chileno del Futuro 96 Future Chilean Cinema Official Selection [27] FICVALDIVIA 7 MUESTRA PARALELA CINEASTAS EN FOCO 105 Video y Estallido Social 178 PARALLEL PROGRAM FILMMAKERS IN THE Video and Social Uprising P. 105 SPOTLIGHT MUESTRA CINE 185 Ana Poliak 106 RETROSPECTIVA RETROSPECTIVE PROGRAM Colectivo Los Hijos 112 Clásicos 186 Latinas a la vanguardia 122 Classics Guillaume Brac 131 VHS Erótico 190 Erotic VHS MUESTRA CINE 139 CONTEMPORÁNEO Vazofi: Bazofi en Valdivia 193 CONTEMPORARY CINEMA Vazofi: Bazofi in Valdivia PROGRAM Gala 140 PÁSATE UNA PELÍCULA 201 Gala WHAT’S YOUR STORY! HOMENAJES 146 Largometrajes familiares 202 TRIBUTES -

Revista De Estudios Sociales, 61

Revista de Estudios Sociales 61 | Julio 2017 Entre lo local y lo global: espacios e interacción en los nuevos enfoques de las ciencias sociales Edición electrónica URL: https://journals.openedition.org/revestudsoc/837 ISSN: 1900-5180 Editor Universidad de los Andes Edición impresa Fecha de publicación: 1 julio 2017 ISSN: 0123-885X Referencia electrónica Revista de Estudios Sociales, 61 | Julio 2017, «Entre lo local y lo global: espacios e interacción en los nuevos enfoques de las ciencias sociales» [En línea], Publicado el 01 julio 2017, consultado el 28 mayo 2021. URL: https://journals.openedition.org/revestudsoc/837 Créditos de la portada Magda Lorena Morales Este documento fue generado automáticamente el 28 mayo 2021. Los contenidos de la Revista de Estudios Sociales están editados bajo la licencia Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. 1 ÍNDICE Editorial Espacios y circulaciones. Nuevas miradas desde las ciencias sociales en América Latina Presentación Fernando Purcell y Andreas E. Feldmann Editorial Martha Lux y Mateo Morales Dossier La construcción de un mundo de regiones Giovanni Molano-Cruz Espacios globales y espacios locales: en busca de nuevos enfoques a los conflictos ambientales. Panorámica sobre Sudamérica y Chile, 2010-2015 Aaron Napadensky y Ricardo Azocar Asociaciones de inmigrantes, Estados y desarrollo entre España y Colombia. ¿Un nuevo campo social transnacional? Joan Lacomba Vázquez y Alexis Cloquell Lozano Experiencias replicables. Análisis de las vinculaciones entre cooperativas de cartoneros, agencias -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

Everything Man Paul Robeson the Form and Function Of

EVERYTHING THE MAN FORM AND FUNCTION PAUL OF ROBESON SHANA L. REDMOND EVERYTHING MAN refiguring american music A series edited by Ronald Radano, Josh Kun, and Nina Sun Eidsheim Charles McGovern, contributing editor duke university press | durham and london | 2020 EVERYTHING MAN THE FORM AND FUNCTION OF PAUL ROBESON shana l. redmond © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Cover designed by Drew Sisk Text designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Whitman by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Redmond, Shana L., author. Title: Everything man : the form and function of Paul Robeson / Shana L. Redmond. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019015468 (print) lccn 2019980198 (ebook) isbn 9781478005940 (hardcover) isbn 9781478006619 (paperback) isbn 9781478007296 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Robeson, Paul, 1898–1976. | Robeson, Paul, 1898–1976—Criticism and interpretation. | Robeson, Paul, 1898–1976—Political activity. | African American singers— Biography. | African American actors—Biography. Classification: lcc e185.97.r63 r436 2020 (print) | lcc e185.97.r63 (ebook) | ddc 782.0092 [b]—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019015468 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019980198 Cover art: Norman Lewis (1909–1979), Too Much Aspiration, 1947. Gouache, ink, graphite, and metallic paint on paper, 21¾ × 30 inches, signed. © Estate of Norman Lewis. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery llc, New York, NY. This book is freely available in an open access edition thanks to tome (Toward an Open Monograph Ecosystem)— a collaboration of the Association of American Universities, the Association of University Presses, and the Association of Research Libraries—and the generous support of Arcadia, a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin, and the ucla Library. -

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 Through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No

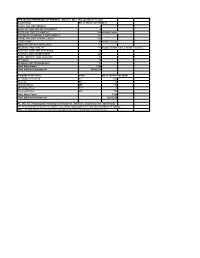

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No. of Stories per Subject AGING AND RETIREMENT 5 AGRICULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT 76 ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT 149 includes Sports BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND FINANCE 103 CRIME AND LAW ENFORCEMENT 168 EDUCATION 42 includes College IMMIGRATION AND REFUGEES 51 MEDICINE AND HEALTH 171 includes Health Care & Health Insurance MILITARY, WAR AND VETERANS 26 POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT 425 RACE, IDENTITY AND CULTURE 85 RELIGION 19 SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 79 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 Program Codes (Pro) Code No. of Stories per Show All Things Considered AT 645 Fresh Air FA 41 Morning Edition ME 513 TED Radio Hour TED 9 Weekend Edition WE 191 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 AT, ME, WE: newsmagazine featuring news headlines, interviews, produced pieces, and analysis FA: interviews with newsmakers, authors, journalists, and people in the arts and entertainment industry TED: excerpts and interviews with TED Talk speakers centered around a common theme Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Aging and Retirement ALL THINGS CONSIDERED 03/23/2021 0:04:22 Hit Hard By The Virus, Nursing Homes Are In An Even More Dire Staffing Situation Aging and Retirement WEEKEND EDITION SATURDAY 03/20/2021 0:03:18 Nursing Home Residents Have Mostly Received COVID-19 Vaccines, But What's Next? Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/15/2021 0:02:30 New Orleans Saints Quarterback Drew Brees Retires Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/12/2021 0:05:15 -

25 Recommended Recordings of Negro

25 Recommended Recordings of Negro Spirituals for Solo Vocalist Compiled by Randye Jones This is a sample of recordings recommended for enhancing library collections of Spirituals and, thus, is limited (with one exception) to recordings available on compact disc. This list includes a variety of voice types, time periods, interpretative styles, and accompaniment. Selections were compiled from The Spirituals Database, a resource referencing more than 450 recordings of Negro Spiritual art songs. Marian Anderson, Contralto He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands (1994) RCA Victor 09026-61960-2 CD, with piano Songs by Hall Johnson, Harry T. Burleigh, Lawrence Brown, J. Rosamond Johnson, Hamilton Forrest, Florence Price, Edward Boatner, Roland Hayes Spirituals (1999) RCA Victor Red Seal 09026-63306-2 CD, recorded between 1936 and 1952, with piano Songs by Hall Johnson, John C. Payne, Harry T. Burleigh, Lawrence Brown, Hamilton Forrest, Robert MacGimsey, Roland Hayes, Florence Price, Edward Boatner, R. Nathaniel Dett Angela Brown, Soprano Mosiac: a collection of African-American spirituals with piano and guitar (2004) Albany Records TROY721 CD, variously with piano, guitar Songs by Angela Brown, Undine Smith Moore, Moses Hogan, Evelyn Simpson- Curenton, Margaret Bonds, Florence Price, Betty Jackson King, Roland Hayes, Joseph Joubert Todd Duncan, Baritone Negro Spirituals (1952) Allegro ALG3022 LP, with piano Songs by J. Rosamond Johnson, Harry T. Burleigh, Lawrence Brown, William C. Hellman, Edward Boatner Denyce Graves, Mezzo-soprano Angels Watching Over Me (1997) NPR Classics CD 0006 CD, variously with piano, chorus, a cappella Songs by Hall Johnson, Harry T. Burleigh, Marvin Mills, Evelyn Simpson- Curenton, Shelton Becton, Roland Hayes, Robert MacGimsey Roland Hayes, Tenor Favorite Spirituals (1995) Vanguard Classics OVC 6022 CD, with piano Songs by Roland Hayes Barbara Hendricks, Soprano Give Me Jesus (1998) EMI Classics 7243 5 56788 2 9 CD, variously with chorus, a cappella Songs by Moses Hogan, Roland Hayes, Edward Boatner, Harry T. -

A Guide for Teaching the Contributions of the Negro Author to American Literature

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 043 635 TE 002 075 AUTHOR Simon, Eugene r. TITLE A Guide for Teaching the Contributions of the Negro Author to American Literature. INSTITUTION San Diego City Schools, Calif. PUB DATE 68 NOTE uln. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.25 BC-$2.1 DESCRIPTORS *African American Studies, *American Literature, Authors, Autobiographies, Piographies, *Curriculum Guides, Drama, Essays, Grade 11, Music, Negro Culture, Negro History, *Negro Literature, Novels, Poetry, Short Stories ABSTRACT This curriculum guide for grade 11 was written to provide direction for teachers in helping students understand how Negro literature reflects its historical background, in integrating Black literature into the English curriculum, in teaching students literary structure, and in comparing and contrasting Negro themes with othr themes in American literature. Brief outlines are provided for four literary periods; (1) the cry for freedom (1619-186c), (2) the period of controversy and search for identity (18(5-1015), (1) the Negro Renaissance (191-1940), and (4) the struggle for equality (101-1968). '*he section covering the Negro Renaissance provides a discussiol of the contributions made during that Period in the fields of the short sto:y, the essay, the novel, poetry, drama, biography, and autobiography.A selected bibliography of Negro literalAre includes works in all these genres as well as works on American Negro music. (D!)) U.S. DIPAIIMINI Of KEITH, MOTION t WItfANI Ulla Of EDUCATION L11 rIN iMIS DOCUMENT HAS SUN IMPRODIXID HAIR IS WINED FROM EIIE PINSON Of ONINI/AliON 011411111110 ElPOINTS Of VIEW Of OPINIONS tes. MUD DO NOT NICISSAINY OMEN! Offg lit OHM Of EDIKIIION POSITION 01 PEW. -

The Creation of a Public Sphere Through a Network of Art Publics in Bogotá

The Creation of a Public Sphere through a Network of Art Publics in Bogotá D I S S E R T A T I O N of the University of St.Gallen, School of Management, Economics, Law, Social Sciences and International Affairs to obtain the title of Doctor of Philosophy in Organizational Studies and Cultural Theory Submitted by Annatina Aerne From Ebnat-Kappel (St.Gallen) Approved on the application of Prof. Dr. Yvette Sánchez and Prof. Dr. Marianne Braig Dissertation no. 4820 Difo-Druck GmbH, Bamberg 2019 The University of St.Gallen, School of Management, Economics, Law, Social Sciences and International Affairs hereby consents to the printing of the present disser- tation, without hereby expressing any opinion on the views herein expressed. St.Gallen, October 15, 2018 The President Prof. Dr. Thomas Bieger 2 Acknowledgements This inquiry would not have started without Professor Yvette Sánchez’ encouragement to do a PhD project on Colombia. Her energy and her ability to see opportunities rather than obstacles, and her willingness to venture into new and unchartered territory are a great inspiration to me. Moreover, her generosity and her warmth provided the basis required to undertake this project: I would not have travelled to Colombia without her support. I was enormously privileged to work with Professor Marianne Braig and Pro- fessor Philip Leifeld. Professor Marianne Braig’s decisive input at the midway point of this project has guided my work to completion. Professor Philip Leifeld has been ex- traordinarily generous, as he repeatedly offered me his time and patiently responded my questions regarding social network analysis. -

The Harlem Renaissance: a Handbook

.1,::! THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY ELLA 0. WILLIAMS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA JULY 1987 3 ABSTRACT HUMANITIES WILLIAMS, ELLA 0. M.A. NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, 1957 THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK Advisor: Professor Richard A. Long Dissertation dated July, 1987 The object of this study is to help instructors articulate and communicate the value of the arts created during the Harlem Renaissance. It focuses on earlier events such as W. E. B. Du Bois’ editorship of The Crisis and some follow-up of major discussions beyond the period. The handbook also investigates and compiles a large segment of scholarship devoted to the historical and cultural activities of the Harlem Renaissance (1910—1940). The study discusses the “New Negro” and the use of the term. The men who lived and wrote during the era identified themselves as intellectuals and called the rapid growth of literary talent the “Harlem Renaissance.” Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925) and James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan (1930) documented the activities of the intellectuals as they lived through the era and as they themselves were developing the history of Afro-American culture. Theatre, music and drama flourished, but in the fields of prose and poetry names such as Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Zora Neale Hurston typify the Harlem Renaissance movement. (C) 1987 Ella 0. Williams All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special recognition must be given to several individuals whose assistance was invaluable to the presentation of this study.