University" Microfilms International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LCSH Section L

L (The sound) Formal languages La Boderie family (Not Subd Geog) [P235.5] Machine theory UF Boderie family BT Consonants L1 algebras La Bonte Creek (Wyo.) Phonetics UF Algebras, L1 UF LaBonte Creek (Wyo.) L.17 (Transport plane) BT Harmonic analysis BT Rivers—Wyoming USE Scylla (Transport plane) Locally compact groups La Bonte Station (Wyo.) L-29 (Training plane) L2TP (Computer network protocol) UF Camp Marshall (Wyo.) USE Delfin (Training plane) [TK5105.572] Labonte Station (Wyo.) L-98 (Whale) UF Layer 2 Tunneling Protocol (Computer network BT Pony express stations—Wyoming USE Luna (Whale) protocol) Stagecoach stations—Wyoming L. A. Franco (Fictitious character) BT Computer network protocols La Borde Site (France) USE Franco, L. A. (Fictitious character) L98 (Whale) USE Borde Site (France) L.A.K. Reservoir (Wyo.) USE Luna (Whale) La Bourdonnaye family (Not Subd Geog) USE LAK Reservoir (Wyo.) LA 1 (La.) La Braña Region (Spain) L.A. Noire (Game) USE Louisiana Highway 1 (La.) USE Braña Region (Spain) UF Los Angeles Noire (Game) La-5 (Fighter plane) La Branche, Bayou (La.) BT Video games USE Lavochkin La-5 (Fighter plane) UF Bayou La Branche (La.) L.C.C. (Life cycle costing) La-7 (Fighter plane) Bayou Labranche (La.) USE Life cycle costing USE Lavochkin La-7 (Fighter plane) Labranche, Bayou (La.) L.C. Smith shotgun (Not Subd Geog) La Albarrada, Battle of, Chile, 1631 BT Bayous—Louisiana UF Smith shotgun USE Albarrada, Battle of, Chile, 1631 La Brea Avenue (Los Angeles, Calif.) BT Shotguns La Albufereta de Alicante Site (Spain) This heading is not valid for use as a geographic L Class (Destroyers : 1939-1948) (Not Subd Geog) USE Albufereta de Alicante Site (Spain) subdivision. -

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 Through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No

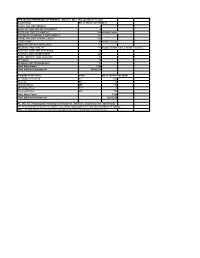

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No. of Stories per Subject AGING AND RETIREMENT 5 AGRICULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT 76 ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT 149 includes Sports BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND FINANCE 103 CRIME AND LAW ENFORCEMENT 168 EDUCATION 42 includes College IMMIGRATION AND REFUGEES 51 MEDICINE AND HEALTH 171 includes Health Care & Health Insurance MILITARY, WAR AND VETERANS 26 POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT 425 RACE, IDENTITY AND CULTURE 85 RELIGION 19 SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 79 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 Program Codes (Pro) Code No. of Stories per Show All Things Considered AT 645 Fresh Air FA 41 Morning Edition ME 513 TED Radio Hour TED 9 Weekend Edition WE 191 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 AT, ME, WE: newsmagazine featuring news headlines, interviews, produced pieces, and analysis FA: interviews with newsmakers, authors, journalists, and people in the arts and entertainment industry TED: excerpts and interviews with TED Talk speakers centered around a common theme Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Aging and Retirement ALL THINGS CONSIDERED 03/23/2021 0:04:22 Hit Hard By The Virus, Nursing Homes Are In An Even More Dire Staffing Situation Aging and Retirement WEEKEND EDITION SATURDAY 03/20/2021 0:03:18 Nursing Home Residents Have Mostly Received COVID-19 Vaccines, But What's Next? Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/15/2021 0:02:30 New Orleans Saints Quarterback Drew Brees Retires Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/12/2021 0:05:15 -

Let the Heavens Rejoice!

April 27, 2018 April 28, 2018 April 29, 2018 St. Noel Church Lakewood Congregational Church Plymouth Church UCC LET THE HEAVENS REJOICE! Concert de Simphonies (1730) – Jacques Aubert (1689–1753) Ouverture – Menuets – Gigues Sarabande – Tambourins – Chaconne In convertendo – Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764) Récit: In convertendo (Owen McIntosh) Choeur: Tunc repletum est gaudio Duo: Magnificavit Dominus (Elena Mullins, Jeffrey Strauss) Récit: Converte Domine captivitatem nostram (Strauss) Choeur dialogué: Laudate nomen Dei (Sarah Coffman) Trio: Qui seminant in lacrimis (McIntosh, Mullins, Strauss) Choeur: Euntes ibant et flebant INTERMISSION Conserva me (1756) – Louis-Antoine Lefebvre (1700–1763) Owen McIntosh, tenor Salve Regina à trois choeurs and basse continue – Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643–1704) Quire Cleveland Venite exultemus (1743) – Jean-Joseph Cassanea de Mondonville (1711–1772) Récit et choeur: Venite exultemus (Mullins, Coffman) Récit: Quoniam Deus Magnus Dominus (Strauss) Récit: Quoniam ipsius est mare (Strauss) Récit: Venite adoremus (Mullins) Récit: Quia ipse est Dominus (Mullins) Récit et choeur: Hodie si vocem (Coffman) Récit: Sicut in exacerbatione (McIntosh) Récit: Quadraginta annis proximus fui (McIntosh) Duo et choeur: Gloria patri (Coffman, Mullins) Quire Cleveland (Ross Duffin, Artistic Director) Les Délices (Debra Nagy, Artistic Director) Scott Metcalfe, Guest Conductor Heartfelt thanks to Charlotte & Jack Newman and Donald W. Morrison for their generous sponsorship of this program. 2017/2018 SEASON anniversaries HELP YOUR and FAVORITE ARTS farewells ORGANIZATION Martin Kessler MUSIC DIRECTOR AS A VOLUNTEER! OPPORTUNITIES INCLUDE: Event Support MAESTRO’S FINAL CONCERT October 15th May 14th at 8pm December 10th Artist Host February 4th Maltz Performing Arts Center at the Temple-Tifereth Israel March 18th Sponsored By Case Western Ambassador Reserve Department of Music Admin. -

Organ Faculty: Marilyn Mason, "The Well·Tempered Chorister" by Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor

THE DIAPASON AN INTERNATIONAL llONTllLl' DEVOTED TO TIlE ORGAN AND THE INTERESTS OF ORGANISTS Sixly-third rt"ar. Nrl. 10 - WI/cle No. i54 SEPTEMHER. 19;2 S"llScript;ollS $4.00 n )'t'ar - 40 cellI! tJ copy University of Iowa Dedicates New Facilities N~chthorn .. fl. The 5Ccond studio organ \\'~5 built Prinzillal 2 h. hf the Moller Organ Company in 1971. "oll£.lole 2 h. The 2i-SIOp. 3-manual instrumcnt has Sc:squiahera II 2% h . Kleinmhtur III I (t. electro· pneumatic key and stop action. Zimhel III y. re. al!d the manual compa5S is 61 noles. Duq ian l ti h. It ill Mollcr'!! opus 10500. Oboe 8 ft. The new Caso\'onl organ in Clapp R,citol Ha:l. KI:.rine -I It. GREAT T U:mui;Ult Ilrill1ipal 8 h. PEDAL Rnhrflnle 8 h. Prinzillal 16 ft. Ocla\·c" h. Subbass 16 It. Dnllblelle 2: h . The School or Music of the Unh'crsity The llIain case contains the Hauptwcrk Okla,· 8 ft . Fourniturc III I ft. of IOW3, Iowa Cit)'. has IlImcd into a and Sthwellwcrk, the Pedal didsion be· Rohrpomlllrr B ft. Sordlln 16 ft. (POIili\') multi-million dollar cOlllpl c: x consisting ing dh'idcd in two cases at each side Cllnralbus .. ft. SWELL of a new Music Building. CIOlPP Recilal o£ the main case £om'ard on the org:tn Rnhr"lrife -I ft. Unurdon 8 fl. Hall, ami Hancher Auditorium. plat£orm. The manual compass is 56 Nachlhorn 2 ft. Sal:cinnal 8 ft. The organ department, which "rof. -

CHAN 0686 BOOK.Qxd 22/5/07 3:06 Pm Page 2

CHAN 0686 Front.qxd 22/5/07 3:04 pm Page 1 CHAN 0686 CHACONNE CHANDOS early music CHAN 0686 BOOK.qxd 22/5/07 3:06 pm Page 2 Elisa is the fayrest Quene 1 Suite of five Galliards 7:51 Galliard I, by Estienne du Tertre (fl. mid-16th century): ‘Galliarde Première’ from Septième Livre de Danceries (Paris, 1557) – Lebrecht Collection Lebrecht Galliard II, by Anonymous, from the Lumley Collection (mid-16th century) – Galliard III, by Pierre Attaingnant (c. 1494–1551/52), from Second Livre de Danceries (Paris, 1547) – Galliard IV, by Anonymous, from the Lumley Collection (mid-16th century) – Galliard V, by Claude Gervaise (fl. 1540–1560): ‘Fin de Galliard’ from Sixième Livre de Danceries (Paris, 1555) Richard Thomas, Rachel Brown, Philip Dale, Adam Woolf, Adrian France, Kathryn Cok; Elizabeth Pallett, Raf Mizraki Edward Johnson (fl. 1572–1601) For the Elvetham entertainment, 1591 2 Elisa is the fayrest Quene, Verse 1 1:08 Stephen Wallace; Richard Thomas, Philip Dale, Adam Woolf, Adrian France, Kathryn Cok 3 Come againe, sweet Nature’s treasure 1:50 Stephen Wallace, Timothy Massa; Philip Dale, Adam Woolf, Adrian France 4 Elisa is the fayrest Quene, Verse 2 1:10 Stephen Wallace; Richard Thomas, Philip Dale, Adam Woolf, Adrian France, Kathryn Cok William Byrd (c. 1540–1623) 5 Fantasia (‘A Lesson of Voluntarie’) 5:21 Title page of John Dowland’s ‘First Booke of Songes Richard Thomas, Rachel Brown, Philip Dale, Adam Woolf, Adrian France, or Ayres’, 1597 Kathryn Cok 3 CHAN 0686 BOOK.qxd 22/5/07 3:06 pm Page 4 John Dowland (?1563–1626) Francis Cutting (before 1571–1596) From The First Booke of Songes or Ayres of fowre partes 10 Divisions on ‘Walsingham’ 3:12 (London, 1597) Elizabeth Pallett 6 Come again, sweet love doth now invite 4:46 Stephen Wallace, Timothy Massa, Julian Podger, Robert McDonald; Antony Holborne (?1545–1602) Richard Thomas, Philip Dale, Adam Woolf, Adrian France; Elizabeth Pallett From Pavans, Galliards, Almains, and other short Aeirs both Robert Parsons (c. -

Guide to the Dowd Harpsichord Collection

Guide to the Dowd Harpsichord Collection NMAH.AC.0593 Alison Oswald January 2012 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: William Dowd (Boston Office), 1958-1993................................................ 4 Series 2 : General Files, 1949-1993........................................................................ 8 Series 3 : Drawings and Design Notes, 1952 - 1990............................................. 17 Series 4 : Suppliers/Services, 1958 - 1988........................................................... -

The University · Mnsical Society

The University ·Mnsical Society \ of The Universi~y 01 Michigan Presents CONCENTUS MUSICUS, VIENNA SATURDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 6, 1971, AT 8:30 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PRO G RAM Concerto in C major TOMASO ALBINONI (1671-1750) Allegro Adagio Allegro Fantasia, "On the Plainsong," Air WILLIAM LAWES (1602-1645) Suite from "Castor and Pollux" JEAN PHILIPPE RAMEAU (1683-1764 ) Ouverture, Menuet-Tambourin, Loure, Gavotte 1,2, Air gay, Entree, Gigue, Chaconne INTERMISSION Three Sonatas from "La Cetra"-1673 GIOVANNI LEGRENZI (1626-1690) Brandenburg Concerto No.5 in D major, BWV 1050, for Harpsichord, Flauto traverso, Violin, and Strings JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750) Allegro Affetuoso Allegro Telefunken and Decca Records Third Concert Ninth Annual Chamber Arl~ Series Complete Program 3740 PROGRAM NOTES The Concentus Musicus plays only on original instruments of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, or on exact copies of these. Even the string instruments have been restored to their original design; they are strung with gut strings and are played with bows of the eighteenth century. The tone of these instruments, and also the playing technique, are distinctly different than those of modern instruments. In other words, old music sounds completely different when played on these instruments rather than on mod ern ones. It should be noted that the old instruments are in no way primitive predecessors of the technically developed modern ones. They are indeed the culmination of their type, as the price of every technical improvement was a degeneration of the tone quality. The Musicians and Their Instruments ALICE HARNONCOURT, Violin Jacobus Stainer, Absam 1665 WALTER PFEIFFER, Violin Matthias Albanus, Bozen 1712 PETER SCHOBERWALTER, Violin Barak Norman, London 1709 JOSEF DE SORDI, Violin . -

Program Notes

PROGRAM NOTES According to the writings of the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates, melancholy was caused by an excess of black bile, one of the four humors. An imbalance of blood, phlegm, yellow bile, or black bile could cause disease—or even determine personality traits. Albrecht Dürer’s famously allegorical “Melencholia I” of 1514 on the program’s cover most likely portrays a morose being who is rendered idle by inspiration’s absence. But for an artist, who can imagine a more destructive affliction than waiting for ideas that just won’t come? During the 16th and 17th centuries, a curious cultural and literary cult of melancholia swept England—in music epitomized by John Dowland’s Lachrimae, or by Shakespeare’s Hamlet— although the Dane’s melancholy probably arose from his paralyzing indecision. And yet, music was considered a cure for melancholy. According to the 17th-century scholar Robert Burton, “Besides that excellent power [music] hath to expel … diseases, it is a sovereign remedy against despair and melancholy….” In any case, depressing subjects certainly stimulate composers’ quirkier ideas and sad music ofen has a cathartic effect on listeners. It is interesting to note that two of the funeral odes on this program do not rely on Christian imagery, but turn to the humanistic Greek mythology of ages past. Although little is known about Anthony Holborne’s life, he was employed by Queen Elizabeth and also admired by his contemporaries. Te esteemed John Dowland dedicated “I Saw My Lady Weepe” from his Second Booke of Songes to him. Holborne composed sixty-five dances that comprise the collection Pavans, Galliards, Almains. -

The Organizer the Atlanta Chapter of the American Guild of Organists

The Organizer The Atlanta Chapter of the American Guild of Organists www.agoatlanta.org Atlanta AGO October 2013 October Dinner Meeting & Recital In this issue… JEAN-BAPTISTE ROBIN at October Meeting ............................................ 1 All Saints’ Episcopal Church About the Recitalist ...................................... 2 634 West Peachtree St NW Atlanta, GA 30308 From the Dean ............................................... 3 (404) 881-0835 October Calendar of Events ...................... 4 Hosts Ray & Beth Chenault Pamela Ingram, and Michael Crowe New Members ................................................. 5 Tuesday, October 15, 2013 Treasurer’s Report ....................................... 6 6:00 p.m. Punchbowl Centennial Celebration ..................... 6/8/9 6:30 p.m. Dinner & Meeting 7:30 p.m. Recital Chaplain’s Corner ......................................... 7 All chapter members who have not already done so AGO Google Groups Replaces ListServ .. 7 are encouraged to pick up their Yearbooks during the Punchbowl portion of the evening. Like us on Facebook! ................................... 7 Around the Chapter ............................. 9/10 Menu Salade niçoise, Coq au vin or Boeuf à la Bourguignonne, Nouilles persillade, Positions Available .................................... 11 Ratatouille, Assortiment de desserts Chapter Officers .......................................... 12 The Organizer, the official bulletin of Program the Atlanta Chapter of the American Louis Marchand, Grand Dialogue in C major Guild of Organists, is published George Bizet, Entr’Acte from Carmen monthly, September through June. All Charles-Marie Widor, Allegro from Symphonie No.6 in G minor, Op. 42 material for publication must reach Claude Debussy, Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune the Editor by the 15th day of the month Marcel Dupré, Second Sketch in B flat minor preceding the date of issue (e.g., No- Jehan Alain, Second Fantasy vember 15 for the December issue). -

December 8, 1972 NO

Madison College Lib? Harrisonburg. Virgin*' / VoL XLVIV Madison College, Harrisonburg Va. Friday, December 8, 1972 NO. 13 Buyers Throng 'Thieves Market' By MARCIA A. SLACUM buyers, the "Market" was On Wednesday, Dec. 6, the located In the more central- Art Student Guild of Madison ized Student Center Ballroom. sponsored a "highly success- Also for the first time, the ful 'Thieves Market' " for sponsors advertised on cam- the sale of arts and crafts. pus and in the city of Har- The sale is an annual event risonburg. and in past years has been held These new methods of pre- in the Duke Fine Arts center. senting the Market appeared This year in order to attract to bring the desired success. and to accommodate more Students and faculty members poured In to the ballroom, par- ticularly between classes and Courses during the dinner hours. The sponsors have always wanted more participation from Offered members of the local com- munity, and this year, Har- Two new inter-dlsclpllnary risonburg residents, mostly Photo by Patrick McLaughlin Humanities courses, Human- women shoppers, patronized The annual "Thieves Market," sponsored by and community to the sale of its arts and ities 300 and Humanities 202, the Market In significant num- the Art Student Guild, was "highly suc- crafts. have been planned for second bers. Marsha Slmms, an Art cessful" in drawing members of the college semester. The two courses major and a member of the are based on a new approach Art Guild, stated that "it was to the arts that will strive really quite exciting. At to -

Leonora Duarte (1610–1678): Converso Composer in Antwerp

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2019 Leonora Duarte (1610–1678): Converso Composer in Antwerp Elizabeth A. Weinfield The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3512 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] LEONORA DUARTE (1610–1678): CONVERSO COMPOSER IN ANTWERP by Elizabeth A. Weinfield A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2019 © 2019 Elizabeth A. Weinfield All Rights Reserved ii Leonora Duarte (1610–1678): Converso Composer in Antwerp by Elizabeth A. Weinfield This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Tina Frühauf Chair of Examining Committee Date Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervising Committee: Emily Wilbourne Janette Tilley Rebecca Cypess THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Leonora Duarte (1610–1678): Converso Composer in Antwerp by Elizabeth A. Weinfield Advisor: Emily Wilbourne Leonora Duarte (1610–1678), a converso of Jewish descent living in Antwerp, is the author of seven five-part Sinfonias for viol consort — the only known seventeenth-century viol music written by a woman. This music is testament to a formidable talent for composition, yet very little is known about the life and times in which Duarte produced her work. -

Flute Violin Harpsichord Conductor Piano Violin

Hodgson School Premier Ensembles Hodgson School of Music “Keys, Winds, and Strings” – A Curious Collection of Concerti by Bach, Stravinsky, and Schnittke. Program Thursday Scholarship Series Thursday April 13 2017 • 7:30 p.m. Bach Concerto for Flute, Violin, Harpsichord, and Orchestra in A Minor, BWV 1044 Allegro Adagio ma non tanto e dolce Tempo di alla breve fluteAngela Jones-Reus Stravinsky Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments Largo – Allegro Shakhida Azimkhodjaeva Larghissimo violin Allegro harpsichordEvgeny Rivkin INTERMISSION conductorJaclyn Hartenberger Schnittke Concerto No. 3 for Violin and Chamber Orchestra pianoAnatoly Sheludyakov Moderato Agitato violinLevon Ambartsumian Andante ARCO Chamber Orchestra The Hugh Hodgson School of Music and the Hugh Hodgson Concert Hall are named in honor of native Athenian and UGA graduate Hugh Leslie Hodgson. In 1928, Hodgson became the University’s first music professor and first chairman of the Department of Music. He retired from the University in 1960. The Thursday Scholarship Series began in 1980 and continues the tradition of “Music Appreciation Programs” started by Hugh Hodgson in the 1930s. Proceeds from these concerts are the primary source of funds for School of Music scholarships. HODGSON CONCERT HALL 42 Performance UGA April 2017 43 Hodgson School Premier Ensembles regional and district honor bands. Her in- Anatoly Sheludyakov was born in Mos- ternational conducting appearances span cow, where he graduated from the Gnessin the Czech Republic, Brazil, and Italy. In Musical Academy. He also graduated from 2014, Hartenberger created UGA’s annual the Moscow Conservatory in the com- Study Abroad Program for undergradu- position class of T. Khrennikov. In 1977, ate conductors.