Copyright by Robert Leland Smale 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of California San Diego

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Infrastructure, state formation, and social change in Bolivia at the start of the twentieth century. A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Nancy Elizabeth Egan Committee in charge: Professor Christine Hunefeldt, Chair Professor Michael Monteon, Co-Chair Professor Everard Meade Professor Nancy Postero Professor Eric Van Young 2019 Copyright Nancy Elizabeth Egan, 2019 All rights reserved. SIGNATURE PAGE The Dissertation of Nancy Elizabeth Egan is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ___________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair ___________________________________________________________ Chair University of California San Diego 2019 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS SIGNATURE PAGE ............................................................................................................ iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................................... iv LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................ vii LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................... ix LIST -

Bulletin De L'institut Français D'études Andines 34 (1) | 2005

Bulletin de l'Institut français d'études andines 34 (1) | 2005 Varia Edición electrónica URL: http://journals.openedition.org/bifea/5562 DOI: 10.4000/bifea.5562 ISSN: 2076-5827 Editor Institut Français d'Études Andines Edición impresa Fecha de publicación: 1 mayo 2005 ISSN: 0303-7495 Referencia electrónica Bulletin de l'Institut français d'études andines, 34 (1) | 2005 [En línea], Publicado el 08 mayo 2005, consultado el 08 diciembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/bifea/5562 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/bifea.5562 Les contenus du Bulletin de l’Institut français d’études andines sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Olivier Dollfus, una pasión por los Andes Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Études Andines / 2005, 34 (1): 1-4 IFEA Olivier Dollfus, una pasión por los Andes Évelyne Mesclier* Henri Godard** Jean-Paul Deler*** En la sabiduría aymara, el pasado está por delante de nosotros y podemos verlo alejarse, mientras que el futuro está detrás nuestro, invisible e irreversible; Olivier Dollfus apreciaba esta metáfora del hilo de la vida y del curso de la historia. En el 2004, marcado por las secuelas físicas de un grave accidente de salud pero mentalmente alerta, realizó su más caro sueño desde hacía varios años: regresar al Perú, que iba a ser su último gran viaje. En 1957, el joven de 26 años que no hablaba castellano, aterrizó en Lima por vez primera, luego de un largo sobrevuelo sobre América del Sur con un magnífico clima, atravesando la Amazonía y los Andes —de los que se enamoró inmediatamente— hasta el desierto costero del Pacífico. -

Línea Base De Conocimientos Sobre Los Recursos Hidrológicos E Hidrobiológicos En El Sistema TDPS Con Enfoque En La Cuenca Del Lago Titicaca ©Roberthofstede

Línea base de conocimientos sobre los recursos hidrológicos e hidrobiológicos en el sistema TDPS con enfoque en la cuenca del Lago Titicaca ©RobertHofstede Oficina Regional para América del Sur La designación de entidades geográficas y la presentación del material en esta publicación no implican la expresión de ninguna opinión por parte de la UICN respecto a la condición jurídica de ningún país, territorio o área, o de sus autoridades, o referente a la delimitación de sus fronteras y límites. Los puntos de vista que se expresan en esta publicación no reflejan necesariamente los de la UICN. Publicado por: UICN, Quito, Ecuador IRD Institut de Recherche pour Le Développement. Derechos reservados: © 2014 Unión Internacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza y de los Recursos Naturales. Se autoriza la reproducción de esta publicación con fines educativos y otros fines no comerciales sin permiso escrito previo de parte de quien detenta los derechos de autor con tal de que se mencione la fuente. Se prohíbe reproducir esta publicación para venderla o para otros fines comerciales sin permiso escrito previo de quien detenta los derechos de autor. Con el auspicio de: Con la colaboración de: UMSA – Universidad UMSS – Universidad Mayor de San André Mayor de San Simón, La Paz, Bolivia Cochabamba, Bolivia Citación: M. Pouilly; X. Lazzaro; D. Point; M. Aguirre (2014). Línea base de conocimientos sobre los recursos hidrológicos en el sistema TDPS con enfoque en la cuenca del Lago Titicaca. IRD - UICN, Quito, Ecuador. 320 pp. Revisión: Philippe Vauchel (IRD), Bernard Francou (IRD), Jorge Molina (UMSA), François Marie Gibon (IRD). Editores: UICN–Mario Aguirre; IRD–Marc Pouilly, Xavier Lazzaro & DavidPoint Portada: Robert Hosfstede Impresión: Talleres Gráficos PÉREZ , [email protected] Depósito Legal: nº 4‐1-196-14PO, La Paz, Bolivia ISBN: nº978‐99974-41-84-3 Disponible en: www.uicn.org/sur Recursos hidrológicos e hidrobiológicos del sistema TDPS Prólogo Trabajando por el Lago Más… El lago Titicaca es único en el mundo. -

EXPERIENCIA EN LA Fiscalía DEPARTAMENTAL DE Potosí AÑOS DE EJERCICIO COMO FISCAL

REFERENCIAS PERSONALES RELACiÓN CURRICULAR DATOS PERSONALES NOMBRE: Antonio Said Leniz Rodríguez FECHA DE NACIMIENTO: 06 de abril de 1972 NACIONALIDAD: Boliviano LUGAR DE NACIMIENTO: Potosí. ciudad, provincia Frías PADRES: Víctor Leniz Virgo Constancia Rodríguez Condori ESTADOCIVIL: Casado CEDULA DE IDENTIDAD: No. 3710893 Exp. En Potosí PROFESION: Abogado MATRICULA PROFESIONAL: ILUSTRECOLEGIO DE ABOGADOS No. 550 MATRICULA PROFESIONAL: MINISTERIODE JUSTICIA:3710893ASLRI-A RADICATORIA ACTUAL: Localidad de Betanzos, Potosí DIRECCION ACTUAL: Ciudad de Potosí. calle 26 de Infantería, Urbanización el Morro No. 22, zona San Martín, ciudad de Potosí. TELEFONO: 62-26711; Cel. 68422230; 67937058. CORREO ELECTRONICO: [email protected] EXPERIENCIA El ejercicio de la profesión de abogado desde la gestión 2000, en el ámbito del derecho penal; en el ejercicio libre de la abogacía, el Poder Judicial-Corte Superior de Distritode Potosí,actual Tribunal Departamental de Justicia de Potosí. Fiscalía Departamental de Potosí, Fiscalía General del Estado en sus instancias de la Inspectoría General del Ministerio Público y Coordinación Nacional en Delitosde Corrupción; finalmente en Fiscalía Departamental de Potosí como Fiscal Departamental SIL. y actualmente como FiscalProvincial. Fiscalía General del Estado y Docencia Universitaria. Adquirió, aptitudes profesionales en la investigación, procesamiento y sanción de casos penales; en todas sus fases en calidad de Asistente Fiscal; Fiscal Asistente; Fiscal Adjunto; Fiscal de Materia, Fiscal Departamental en SIL; en el inicio, investigación de procesos penales en todas sus Fiscalías y reparticiones. Fiscal Inspector en el Régimen Disciplinario del Ministerio Público, con la investigación, procesamiento de procesos disciplinarios. Coordinación Nacional en Delitos contra la Corrupción de la Fiscalía General, con investigación, procesamiento y sanción de casos penales de corrupción. -

Download Print Version (PDF)

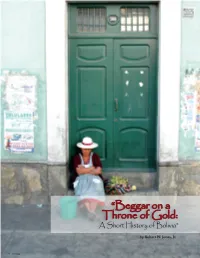

“Beggar on a Throne of Gold: A Short History of Bolivia” by Robert W. Jones, Jr. 6 Veritas is a land of sharp physical and social contrasts. Although blessed with Benormousolivia mineral wealth Bolivia was (and is) one of the poorest nations of Latin America and has been described as a “Beggar on a Throne of Gold.” 1 This article presents a short description of Bolivia as it appeared in 1967 when Che Guevara prepared to export revolution to the center of South America. In Guevara’s estimation, Bolivia was ripe for revolution with its history of instability and a disenfranchised Indian population. This article covers the geography, history, and politics of Bolivia. Geography and Demographics Bolivia’s terrain and people are extremely diverse. Since geography is a primary factor in the distribution of the population, these two aspects of Bolivia will be discussed together. In the 1960s Bolivian society was predominantly rural and Indian unlike the rest of South America. The Indians, primarily Quechua or Aymara, made up between fifty to seventy percent of the population. The three major Indian dialects are Quechua, Aymara, and Guaraní. The remainder of the population were whites and mixed races (called “mestizos”). It is difficult to get an accurate census because The varied geographic regions of Bolivia make it one of the Indians have always been transitory and there are the most climatically diverse countries in South America. cultural sensitivities. Race determines social status in Map by D. Telles. Bolivian society. A mestizo may claim to be white to gain vegetation grows sparser towards the south, where social status, just as an economically successful Indian the terrain is rocky with dry red clay. -

Apoyo Y Promoción De La Producción Indígena Originaria Campesina Familiar Y Comunitaria En Bolivia»

Convenio «Apoyo y promoción de la producción indígena originaria campesina familiar y comunitaria en Bolivia» - Objetivo del Convenio: • “Promover un modelo de desarrollo rural justo a favor de la Soberanía Alimentaria (Sba), como propuesta que dignifique la vida campesina indígena originaria y garantice el derecho a la alimentación en Bolivia” Áreas de intervención: Local = Ayllu productivo Nacional = Incidencia SbA Internacional = Articulación SbA - MT - CC El convenio articula acciones a nivel regional, nacional y local. Por tanto su intervención es integral. Actores relevantes: ACCIÓN 7 Promover una estrategia de producción, transformación y comercialización indígena originaria familiar y comunitaria sobre bases agroecológicas y priorizando los mercados de proximidad y las ventas estatales. PLAN DE GESTIÓN – CONAMAQ 2010-2014 Implementación legislativa - Relaciones internacionales Reconstitución - Diplomacia Estratégica Estrategia comunicacional - Líneas estratégicas Fortalecimiento del definidas gobierno originario Fortalecimiento a de la producción nativa agroecológica y etnoveterinaria Cultura e identidad económico – productivo, Problemas educación, género, identificados salud, justicia indígena, tierra y territorio, recursos naturales y medio ambiente, comunicación . Política económica Mercado interno de Macro Política alimentos (grande) comercial INTERPRETACIÓN Política agropecuaria Comercio exterior Soberanía Tierra, agua Visión Alimentaria Go-gestión entre el Estado y la integral sociedad civil Autoconsumo Micro (muy Seguridad -

Wild Potato Species Threatened by Extinction in the Department of La Paz, Bolivia M

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Scientific Journals of INIA (Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Tecnología Agraria y Alimentaria) Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Tecnología Agraria y Alimentaria (INIA) Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research 2007 5(4), 487-496 Available online at www.inia.es/sjar ISSN: 1695-971-X Wild potato species threatened by extinction in the Department of La Paz, Bolivia M. Coca-Morante1* and W. Castillo-Plata2 1 Facultad de Ciencias Agrícolas, Pecuarias, Forestales y Veterinarias. Dr. «Martín Cárdenas» (FCA, P, F y V). Universidad Mayor de San Simón (UMSS). Casilla 1044. Cochabamba. Bolivia 2 Medio Ambiente y Desarrollo (MEDA). Cochabamba. Bolivia Abstract The Department of La Paz has the largest number of wild potato species (Solanum Section Petota Solanaceae) in Bolivia, some of which are rare and threatened by extinction. Solanum achacachense, S. candolleanum, S. circaeifolium, S. okadae, S. soestii and S. virgultorum were all searched for in their type localities and new areas. Isolated specimens of S. achacachense were found in its type localities, while S. candolleanum was found in low density populations. Solanum circaeifolium was also found as isolated specimens or in low density populations in its type localities, but also in new areas. Solanum soestii and S. okadae were found in small, isolated populations. No specimen of S. virgultorum was found at all. The majority of the wild species searched for suffered the attack of pathogenic fungi. Interviews with local farmers revealed the main factors negatively affecting these species to be loss of habitat through urbanization and the use of the land for agriculture and forestry. -

265 Lengua X

LENGUA X: AN ANDEAN PUZZLE 1 MATTHIAS PACHE LEIDEN UNIVERSITY In the south-central Andes, several researchers have documented series of numerical terms that some have attributed to a hitherto unknown language: Lengua X. Indeed, they are difficult to link, as a whole, with numerical series from the known languages of the area. This paper discusses the available information on these series and attempts to trace their origin. It is difficult to argue that they are the remnants of a single, vanished language. Instead, it is argued that Lengua X numbers for ‘one’ and ‘two’ originate in Aymara, a language from the highlands, whereas terms for ‘three’ to ‘five’ originate in Mosetén, a language from the eastern foothills. Additional parallels with Uru-Chipayan, Quechua, and Aymara (terms from ‘six’ to ‘ten’) suggest that Lengua X numbers reflect a unique and complex situation of language contact in the south-central Andes. [KEYWORDS: Lengua X, Aymara, Mosetén, Uru-Chipayan, numbers, language contact] 1. Introduction. Since the colonial period, four indigenous language groups have been associated with the south-central Andes: Quechua, Ay- mara, Uru-Chipayan, and Puquina (e.g., Bouysse-Cassagne 1975; Adelaar 2004). Since the late nineteenth century, however, several researchers (e.g., Posnansky 1938; Vellard 1967) have come across words in the Bolivian highlands for numbers that seem to belong to a different language: Lengua X, as it was called by Ibarra Grasso (1982:15, 97). This paper presents and discusses Lengua X numerical terms, addressing the question of their origin. Table 1 illustrates the first four numbers of Lengua X, together with their counterparts in Aymara, Chipaya (Uru-Chipayan), Bolivian Quechua, and Puquina. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 59305-BO PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED CREDIT Public Disclosure Authorized IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 69.65 MILLLION (US$ 109.5 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE PLURINATIONAL STATE OF BOLIVIA FOR THE NATIONAL ROADS AND AIRPORT INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized April 06, 2011 Sustainable Development Department Country Management Unit for Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela Latin America and the Caribbean Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective March 4, 2011) Currency Unit = Bolivian Bolivianos BOB7.01 = US$1 US$1.58 = SDR1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AASANA Administración de Aeropuertos y Servicios Auxiliares a la Navegación Aérea Airport and Aviation Services Administration ABC Administradora Boliviana de Carreteras National Road Agency ABT Autoridad de Bosques y Tierra Authority on Forest and Land ADT Average Daily Traffic CIPTA Consejo Indígena del Pueblo Tacana Counsel for the Indigeneous Tacana People DA Designated Account EA Environmental Assessment EIRR Economic Internal Rate of Return EMP Environmental Management Plan FM Financial Management GAC Governance and Anti-corruption GDP Gross Domestic Product GOB Government of Bolivia HDM-4 Highway -

I.V. V. Bolivia

I.V. v. Bolivia ABSTRACT1 This case is about the sterilization, by tubal ligation, of a woman without her prior consent. The Court found violations of both the American Convention and the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence Against Women (“Convention of Belém do Para”). It did not discuss, however, the violation of the Right to Health (Art. 26 of the Convention) implicated in the case. I. FACTS A. Chronology of Events 1982: I.V., a Peruvian citizen, gives birth to her first daughter.2 Late 1980’s–Early 1990s: I.V. is the victim of physical, sexual and psychological harassment perpetrated by the National Directorate Against Terrorism of Peru (DINCOTE).3 1989: I.V. meets J.E., and they begin a romantic relationship.4 1991: Their daughter N.V. is born.5 1993: J.E. migrates to La Paz, Bolivia, from Peru where he is granted refugee status.6 1. Sebastian Richards, Staffer; Edgar Navarette, Editor; Erin Gonzalez, Chief IACHR Editor; Cesare Romano, Faculty Advisor. 2. I.V. v. Bolivia, Preliminary Objections, Merits, Reparations and Costs, Judgment, Inter- Am. Ct. H.R. (ser. C) No. 336, ¶ 61 (Nov. 30, 2016). (Available only in Spanish). 3. Id. 4. Id. 5. Id. 6. Id. 1351 1352 Loy. L.A. Int‟l & Comp. L. Rev. Vol. 41:4 1994: N.V. and I.V. join him in La Paz in 1994 and receive refugee status two months later.7 While in La Paz, I.V. obtains a hotel administration degree.8 February 2000: I.V., now age 35, is pregnant with her third daughter.9 She applies for Bolivia’s universal maternal and child health insurance, and basic health insurance and begins to receive pre-natal health care from the La Paz Women’s Hospital.10 July 1, 2000: I.V. -

10 Políticas Del Municipio Colquencha

PLAN DE DESARROLLO MUNICIPAL Colquencha Plan de Desarrollo Municipal Colquencha ii ÍNDICE . 1 ASPECTOS POLITICOS ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 UBICACIÓN Y LONGITUD .................................................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Localización .................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1.2 Latitud y longitud .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1.3 Limites territoriales ...................................................................................................................... 1 1.1.4 Extensión ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 DIVISIÓN POLÍTICA ADMINISTRATIVA Y ORGANIZACIÓN SINDICAL ..................................................... 2 1.2.1 Distritos y cantones ....................................................................................................................... 2 1.2.2 Organización sindical ................................................................................................................... 3 1.3 MANEJO ESPECIAL ............................................................................................................................. 3 1.3.1 Uso y ocupación -

Ethnohistoire Du Piémont Bolivien D'apolobamba À Larecaja

RENAISSANCE OF THE LOST LECO: ETHNOHISTORY OF THE BOLIVIAN FOOTHILLS FROM APOLOBAMBA TO LARECAJA Francis Ferrié A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2014 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/4867 This item is protected by original copyright Renaissance of the Lost Leco: Ethnohistory of the Bolivian Foothills from Apolobamba to Larecaja Francis Ferrié A Thesis to be submitted to Université de Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense and University of St Andrews for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Social Anthropology School of Philosophical, Anthropological and Film Studies University of St Andrews A Join PhD with Université de Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense Ecole Doctorale Milieux, Cultures et Sociétés du Passé et du Présent 29th of January 2014 2 DECLARATIONS 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Francis Ferrié, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a candidate for the joint degree of PhD in Social Anthropology in September, 2008; the higher study of which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews and the Université de Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense between 2008 and 2013. Francis Ferrié, 15/05/2014 2.