BONY-AMC.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Questions to Russian Archives – Short

The Raoul Wallenberg Research Initiative RWI-70 Formal Request to the Russian Government and Archival Authorities on the Raoul Wallenberg Case Pending Questions about Documentation on the 1 Raoul Wallenberg Case in the Russian Archives Photo Credit: Raoul Wallenberg’s photo on a visa application he filed in June 1943 with the Hungarian Legation, Stockholm. Source: The Hungarian National Archives, Budapest. 1 This text is authored by Dr. Vadim Birstein and Susanne Berger. It is based on the paper by V. Birstein and S. Berger, entitled “Das Schicksal Raoul Wallenbergs – Die Wissenslücken.” Auf den Spuren Wallenbergs, Stefan Karner (Hg.). Innsbruck: StudienVerlag, 2015. S. 117-141; the English version of the paper with the title “The Fate of Raoul Wallenberg: Gaps in Our Current Knowledge” is available at http://www.vbirstein.com. Previously many of the questions cited in this document were raised in some form by various experts and researchers. Some have received partial answers, but not to the degree that they could be removed from this list of open questions. 1 I. FSB (Russian Federal Security Service) Archival Materials 1. Interrogation Registers and “Prisoner no. 7”2 1) The key question is: What happened to Raoul Wallenberg after his last known presence in Lubyanka Prison (also known as Inner Prison – the main investigation prison of the Soviet State Security Ministry, MGB, in Moscow) allegedly on March 11, 1947? At the time, Wallenberg was investigated by the 4th Department of the 3rd MGB Main Directorate (military counterintelligence); -

The Russia You Never Met

The Russia You Never Met MATT BIVENS AND JONAS BERNSTEIN fter staggering to reelection in summer 1996, President Boris Yeltsin A announced what had long been obvious: that he had a bad heart and needed surgery. Then he disappeared from view, leaving his prime minister, Viktor Cher- nomyrdin, and his chief of staff, Anatoly Chubais, to mind the Kremlin. For the next few months, Russians would tune in the morning news to learn if the presi- dent was still alive. Evenings they would tune in Chubais and Chernomyrdin to hear about a national emergency—no one was paying their taxes. Summer turned to autumn, but as Yeltsin’s by-pass operation approached, strange things began to happen. Chubais and Chernomyrdin suddenly announced the creation of a new body, the Cheka, to help the government collect taxes. In Lenin’s day, the Cheka was the secret police force—the forerunner of the KGB— that, among other things, forcibly wrested food and money from the peasantry and drove some of them into collective farms or concentration camps. Chubais made no apologies, saying that he had chosen such a historically weighted name to communicate the seriousness of the tax emergency.1 Western governments nod- ded their collective heads in solemn agreement. The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank both confirmed that Russia was experiencing a tax collec- tion emergency and insisted that serious steps be taken.2 Never mind that the Russian government had been granting enormous tax breaks to the politically connected, including billions to Chernomyrdin’s favorite, Gazprom, the natural gas monopoly,3 and around $1 billion to Chubais’s favorite, Uneximbank,4 never mind the horrendous corruption that had been bleeding the treasury dry for years, or the nihilistic and pointless (and expensive) destruction of Chechnya. -

La Russie De 1991 À Nos Jours

La Russie de 1991 à nos jours Contenu : Introduction : L’indépendance de la Fédération de Russie ..................................................................... 1 I- La Russie d’Eltsine : des débuts difficiles ............................................................................................. 2 A) L’échec de la thérapie de choc et du virage libéral ........................................................................ 2 B) Un repli sur ses propres conflits internes ....................................................................................... 3 C) Un niveau de vie en baisse manifeste ............................................................................................. 4 II- Sous Poutine, vers un nouveau départ ?............................................................................................. 5 A) Une expansion économique remarquable ..................................................................................... 5 B) Un retour sur la scène internationale, mais tensions persistantes au sein de l’ex-URSS ............... 6 C) Un Etat-providence limité et une démocratie remise en cause : la Russie, Etat non-occidental ... 7 III- Un retour en force sur la scène internationale .................................................................................. 8 A) Une politique d’expansion à nouveau clairement visible ............................................................... 8 B) Un nouveau statut sur la scène internationale et la construction d’un bloc eurasiatique ............. 9 C) -

Temptation to Control

PrESS frEEDOM IN UKRAINE : TEMPTATION TO CONTROL ////////////////// REPORT BY JEAN-FRANÇOIS JULLIARD AND ELSA VIDAL ////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// AUGUST 2010 /////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// PRESS FREEDOM: REPORT OF FACT-FINDING VISIT TO UKRAINE ///////////////////////////////////////////////////////// 2 Natalia Negrey / public action at Mykhaylivska Square in Kiev in November of 2009 Many journalists, free speech organisations and opposition parliamentarians are concerned to see the government becoming more and more remote and impenetrable. During a public meeting on 20 July between Reporters Without Borders and members of the Ukrainian parliament’s Committee of Enquiry into Freedom of Expression, parliamentarian Andrei Shevchenko deplored not only the increase in press freedom violations but also, and above all, the disturbing and challenging lack of reaction from the government. The data gathered by the organisation in the course of its monitoring of Ukraine confirms that there has been a significant increase in reports of press freedom violations since Viktor Yanukovych’s election as president in February. LEGISlaTIVE ISSUES The government’s desire to control journalists is reflected in the legislative domain. Reporters Without Borders visited Ukraine from 19 to 21 July in order to accomplish The Commission for Establishing Freedom the first part of an evaluation of the press freedom situation. of Expression, which was attached to the presi- It met national and local media representatives, members of press freedom dent’s office, was dissolved without explanation NGOs (Stop Censorship, Telekritika, SNUJ and IMI), ruling party and opposition parliamentarians and representatives of the prosecutor-general’s office. on 2 April by a decree posted on the president’s At the end of this initial visit, Reporters Without Borders gave a news conference website on 9 April. -

Respondent Motion to Dismiss Petition to Confirm Award

Case 1:14-cv-01996-ABJ Document 24 Filed 10/20/15 Page 1 of 55 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) HULLEY ENTERPRISES LTD., ) YUKOS UNIVERSAL LTD., and ) VETERAN PETROLEUM LTD., ) ) Petitioners, ) ) Case No. 1:14-cv-01996-ABJ v. ) ) THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION ) ) Respondent. ) ) RESPONDENT’S MOTION TO DISMISS THE PETITION TO CONFIRM ARBITRATION AWARDS FOR LACK OF SUBJECT MATTER JURISDICTION Pursuant to Rule 12(b)(1) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and the Court’s Minute Orders of August 4, 2015 and October 19, 2015, Respondent, the Russian Federation, respectfully submits this motion to dismiss the Petitioners’ Petition to Confirm Arbitration Awards, in its entirety, for lack of subject matter jurisdiction. Pursuant to Rule 7(a) of the Civil Rules of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, Respondent submits herewith a Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of its Motion to Dismiss. Respondent also submits the following documents, with exhibits, in further support of its Motion to Dismiss: 1. The Declaration of Gitas Povilo Anilionis, dated October 16, 2015, describing the control structure of SP Russian Trust and Trade (“RTT”) and its role in the acquisition and subsequent transfers of the Yukos shares; Case 1:14-cv-01996-ABJ Document 24 Filed 10/20/15 Page 2 of 55 2. The Declaration of Arkady Vitalyevich Zakharov, dated October 14, 2015, describing the control structure of Menatep Group and IF Menatep and its role, along with RTT, in the acquisition and subsequent transfers of the Yukos shares; 3. The Declaration of Colonel of Justice Sergey A. -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

Case 1:14-cv-01996-ABJ Document 24-1 Filed 10/20/15 Page 1 of 39 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) HULLEY ENTERPRISES LTD., ) YUKOS UNIVERSAL LTD., and ) VETERAN PETROLEUM LTD., ) ) Petitioners, ) ) v. ) Case No. 1:14-cv-01996-ABJ ) ) THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION, ) ) Respondent. ) ) DECLARATION OF GITAS POVILO ANILIONIS I, Gitas Povilo Anilionis, declare and state as follows: 1. I was born in 1953 in the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic. I have lived in Moscow since 1976 and I am a Russian citizen. Since 2002, I have been the general director of a company called OOO Lion XXI, which provides financial consulting and market research services for business clients. 2. I completed high school in 1971 and from 1971 to 1974 I studied at the Department of Mathematics and Mechanics of Vilnius State University with a specialization in applied mathematics. From 1974 until 1976, I served in the Soviet army. In 1976, I came to live in Moscow and studied economics at the University of the Friendship of Nations named after Patrice Lumumba. I graduated in 1982, and worked until 1986 in Nigeria on the construction of metallurgical plant in Ajaokuta, which was an economic-development effort supported by the Case 1:14-cv-01996-ABJ Document 24-1 Filed 10/20/15 Page 2 of 39 Soviet Union. I then returned from Nigeria to Moscow in 1986 and worked until November 1990 in a cooperative known as Geology Abroad (Ɂɚɪɭɛɟɠɝɟɨɥɨɝɢɹ) in the economic planning department. 3. At Geology Abroad, my supervisor was Mr. Platon Leonidovich Lebedev. -

Berezovsky-Judgment.Pdf

Neutral Citation Number: [2012] EWHC 2463 (Comm) Royal Courts of Justice Rolls Building, 7 Rolls Buildings, London EC4A 1NL Date: 31st August 2012 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE Case No: 2007 Folio 942 QUEEN’S BENCH DIVISION COMMERCIAL COURT IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE Claim Nos: HC08C03549; HC09C00494; CHANCERY DIVISION HC09C00711 Before: MRS JUSTICE GLOSTER, DBE - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between: Boris Abramovich Berezovsky Claimant - and - Roman Arkadievich Abramovich Defendant Boris Abramovich Berezovsky Claimant - and - Hine & Others Defendants - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Laurence Rabinowitz Esq, QC, Richard Gillis Esq, QC, Roger Masefield Esq, Simon Colton Esq, Henry Forbes-Smith Esq, Sebastian Isaac Esq, Alexander Milner Esq, and Ms. Nehali Shah (instructed by Addleshaw Goddard LLP) for the Claimant Jonathan Sumption Esq, QC, Miss Helen Davies QC, Daniel Jowell Esq, QC, Andrew Henshaw Esq, Richard Eschwege Esq, Edward Harrison Esq and Craig Morrison Esq (instructed by Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP) for the Defendant Ali Malek Esq, QC, Ms. Sonia Tolaney QC, and Ms. Anne Jeavons (instructed by Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer LLP) appeared for the Anisimov Defendants to the Chancery Actions David Mumford Esq (instructed by Macfarlanes LLP) appeared for the Salford Defendants to the Chancery Actions Jonathan Adkin Esq and Watson Pringle Esq (instructed by Signature Litigation LLP) appeared for the Family Defendants to the Chancery Actions Hearing dates: 3rd – 7th October 2011; 10th – 13th October 2011; 17th – 19th October 2011; 24th & 28th October 2011; 31st October – 4th November 2011; 7th – 10th November 2011; 14th - 18th November 2011; 21st – 23 November 2011; 28th November – 2nd December 2011; 5th December 2011; 19th & 20th December 2011; 17th – 19th January 2012. -

Wiira No Me Mar.Pdf (2.061Mb)

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL PAULISTA “JÚLIO DE MESQUITA FILHO” FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS NAYARA DE OLIVEIRA WIIRA UMA ANÁLISE DA ESTRUTURAÇÃO DO CAPITALISMO RUSSO ATRAVÉS DA PRIVATIZAÇÃO NO GOVERNO YELTSIN (1991-1999). MARÍLIA 2020 NAYARA DE OLIVEIRA WIIRA UMA ANÁLISE DA ESTRUTURAÇÃO DO CAPITALISMO RUSSO ATRAVÉS DA PRIVATIZAÇÃO NO GOVERNO YELTSIN (1991-1999). Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Sociais da Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências, da Universidade Estadual Paulista – UNESP – Campus de Marília, para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências Sociais. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Francisco Luiz Corsi MARÍLIA 2020 Wiira, Nayara de Oliveira W662a Uma análise da estruturação do capitalismo russo através da privatização no governo Yeltsin (1991-1999) / Nayara de Oliveira Wiira. -- Marília, 2020 280 f. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Estadual Paulista (Unesp), Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências, Marília Orientador: Francisco Luiz Corsi 1. História econômica. 2. História econômica russa. 3. Privatização. 4. Capitalismo. I. Título. Sistema de geração automática de fichas catalográficas da Unesp. Biblioteca da Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências, Marília. Dados fornecidos pelo autor(a). Essa ficha não pode ser modificada. NAYARA DE OLIVEIRA WIIRA UMA ANÁLISE DA ESTRUTURAÇÃO DO CAPITALISMO RUSSO ATRAVÉS DA PRIVATIZAÇÃO NO GOVERNO YELTSIN (1991-1999). Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Sociais da Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências, da Universidade Estadual Paulista – UNESP – Campus de Marília, para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências Sociais. Linha de pesquisa 4: Relações Internacionais e Desenvolvimento BANCA EXAMINADORA ________________________________________ Orientador: Prof. Dr. Francisco Luiz Corsi Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências ________________________________________ Prof. -

Infographics in Booklet Format

SWITZERLAND CHINA 243 535 ITALY AUSTRALIA 170 183 State of Corporate pOWER 2012 Toyota Motor Exxon Mobil Wal-Mart Stores $ Royal Dutch Shell Barclays plc 60 USA Capital Group Companies 28 Japan 20 China Carlos Slim Helu Mexico telecom 15000 T 10000 op 25 global companies based ON revenues A FOssIL-FUELLED WORLD 5000 Wal-Mart Stores 3000 AUTO Toyota Motor retail Volkswagen Group 2000 General Motors Daimler 1000 Group 203 S AXA Ford Motor 168 422 136 REVENUES US$BILLION OR Royal C Group 131 OIL Dutch powerorporationsFUL THAN nationsMORE ING Shell 2010 GDP 41 OF THE World’S 100 L 129 EC ONOMIE Allianz Nation or Planet Earth Company 162 USA S ARE C China F Japan INANCIAL 149 A Germany ORP France ORatIONARS Corpor United Kingdom GE 143 Brazil st Mobil Exxon Italy Hathaway India Berkshire 369 Canada Russia Spain 136 Australia Bank of America Mexico 343 BP Korea Netherlands Turkey 134 Indonesia ate Switzerland BNP 297 Paribas Poland Oil and gas make Belgium up eight of the top Group Sweden 130 Sinopec Saudi Arabia ten largest global Taiwan REVENUES World US$BILLIONS 273 corporations. Wal-Mart Stores Norway Iran Royal Dutch Shell 240 China Austria Petro Argentina South Africa 190 Exxon Mobil Thailand Denmark 188 BP Chevron 176 131 127 134 150 125 Total Greece United Arab Emirates Venezuela Hewlett Colombia Packard other Samsung ENI Conoco Sinopec Group Electronics Phillips PetroChina E.ON Finland General Malaysia Electric Portugal State Grid Hong Kong SAR Singapore Toyota Motor http://www.minesandcommunities.org Egypt http://europeansforfinancialreform.org -

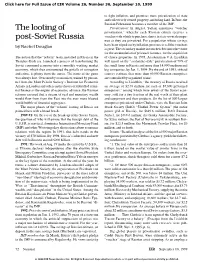

The Looting of Post-Soviet Russia

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 26, Number 36, September 10, 1999 to fight inflation, and promises mass privatization of state and collectively owned property, including land. In June, the Russian Federation becomes a member of the IMF. The looting of Privatization: In August, Yeltsin announces “voucher privatization,” whereby each Russian citizen receives a post-Soviet Russia voucher with which to purchase shares in state-owned compa- nies as they are privatized. For a population whose savings by Rachel Douglas have been wiped out by inflation, pressure to sell the vouchers is great. The secondary market in vouchers becomes the venue for the accumulation of privateer fortunes, for the acquisition The notion that the “reform” team, installed in Russia in the of choice properties. In 1995, Academician V.A. Lisichkin Thatcher-Bush era, launched a process of transforming the will report on the “avalanche-style” privatization of 70% of Soviet command economy into a smoothly working market the small firms in Russia and more than 14,000 medium and economy, which then encountered the pitfalls of corruption big companies, by Jan. 1, 1994. By the end of 1993, official and crime, is phony from the outset. The name of the game sources estimate that more than 60,000 Russian enterprises was always loot. Overseen by economists, trained by person- are controlled by organized crime. nel from the Mont Pelerin Society’s Institute for Economic According to Lisichkin, “the treasury of Russia received Affairs in London and others in the theory of unbridled crimi- an average of $2.48 million for each of 87,600 privatized nal finance as the engine of economic advance, the Russian enterprises,” among which were jewels of the Soviet econ- reforms ensured that a stream of real and monetary wealth omy, sold for a tiny fraction of the real worth of their plant would flow from from the East into the ever more bloated and equipment and their products. -

Yukos Oil: a Corporate Governance Success Story?

Yukos Oil: A Corporate Governance Success Story? Diana Yousef-Martinek MBA/MIA ‘04 Raphael Minder Knight-Bagehot Fellow‘03 Rahim Rabimov MS ‘03 © 2003 by The Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York. All rights reserved. CHAZEN WEB JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS FALL 2003 www.gsb.columbia.edu/chazenjournal 1. Introduction In what would become post-Communist Russia’s largest takeover transaction, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the controversial 39-year old chief executive and controlling shareholder of the Russian oil company Yukos, announced last April that Yukos would buy Sibneft, the fastest growing Siberian oil corporation. The Yukos-Sibneft merger created the world's fourth-largest company in terms of oil production, dwarfed only by ExxonMobil, BP, and Royal Dutch Shell. The new company projected a daily output of 2.06 million barrels, more than 25 percent of Russia’s total, and it has total reserves of about 19.4 billion barrels. It was expected to generate $15 billion in revenues every year and boasted a market value of about $35 billion.1 How has Khodorkovsky, who only a few years ago was making newspaper headlines for his business practices, managed to become the champion of a new corporate Russia? Is the transformation for real or just short-term opportunism? This paper will examine the way in which Khodorkovsky moved from banking to the oil business, benefiting from the tumultuous changes in Russia, and how he slowly came to espouse a Western model of corporate governance and management. The paper will also discuss a number of external factors, such as the Russian legal system, which have helped Khodorkovsky in his rise while making it difficult for investors to assess Yukos’ performance and predict its future. -

Appendix 1 State’S Share in Oil Production, 1994–2006 (As % of Total Oil Production)

Appendix 1 State’s Share in Oil Production, 1994–2006 (as % of Total Oil Production) 90 80 70 60 50 % 40 30 20 10 0 1994 1995 19971996 1998 19992000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 All state-owned companies Companies owned by federation Companies owned by regional governments Source: Julia Kuzsnir and Heiko Pleines, ‘The Russian Oil Industry between Foreign Investment and Domestic Interests in Russian Analytical Digest, 18 September 2007, p. 14. 131 Appendix 2 Results of Loans-for-Shares Privatization in the Oil Industry Trust auctions, 1995 Collateral auctions, 1996–1997 Stake Min. Name under Loan Organizer sale of oil auction provided Auction for Auction price Auction Price Auction company (%) (US$m) date auction winner (US$m) date paid winner Surgut- 40.12 88.3 Nov 95 ONEKSIM bank Surgutneftegaz 74 Feb 97 78.8 Surgutfondinvest neftegaz pension fund (linked to 132 Surgutneftegaz) LUKoil 5 35.01 Dec 95 Imperial Bank LUKoil Imperial 43 Jun 97 43.6 LUKoil (LUKoil affiliate) Bank Reserve-Invest YUKOS 45 159 Dec 95 Menatep Bank Laguna (Menatep 160 Nov 96 160.1 Monblan (Menatep affiliate) affiliate) SIDANKO 51 130 Dec 95 ONEKSIM bank MFK (part of 129 Jan 97 129.8 Interros Oil ONEKSIM bank) (part of ONEKSIM bank group) Sibneft’ 51 100.1 Dec 95 Menatep Bank NFK, SBS 101 May 97 110 FNK (offshoot (linked to of NFK) Sibneft’) Sources: Valery Kryukov and Arild Moe. The Changing Role of Banks in the Russian Oil Sector. London: Royal Institute of International Affairs, 1998; Nat Moser and Peter Oppenheimer. ‘The Oil Industry: Structural Transformation and Corporate Governance’.