'You're Gonna Need Someone on Your Side': Morrissey's Latino/A And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sidvd504 Musicspectr

Music Spectrum Page 5 of 23 death: “Dear God, take him, take them, take anyone, the stillborn, the newborn, the NorthernBlue infirm, take anyone, take people from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, just spare me.” Most of us 95North Reco wouldn’t say it out loud, but Morrissey outs our true sinister thoughts that pass through Or Music our brains. Palm Pictures Parasol Planetary Gro The Smiths: Under Review, An Provident Lab Independent Critical Analysis Righteous Ba The traditional topics in any Smiths Rhino biography are all covered here: the band Rough Trade name, traditional four piece lineup, Runway Netw ambiguous nature of Morrissey’s Ryko Music sexuality, being a household name in the Salt Lady Re UK (but not the U.S.), “Suffer Little Sanctuary Re Children” (Moors murders), album sleeves, singles slump, role of Mike Joyce Sounds Fami and Andy Rourke, reluctance to do videos Special Ops M in MTV era, Craig Gannon, and the split. Team Clermo However, while some of the information Theory 8 Rec may not be new, because The Smiths: Telarc Under Review, An Independent Critical Analysis is a video documentary, it is a comforting Transmit Sou companion for any Smiths fan or seeker. TVT Records Unschooled Having never attended a Smiths Convention http://www.musicconventions.com/, and Vanguard Re having very few close friends who are Smiths fans, sitting and watching so many writers, Wampus Rec musicians, and people in the circle discuss what the Smiths meant and mean is like Warp Record discovering that you’re not alone. Others have also spent hours thinking about why this Wind-up Rec band affected them so much. -

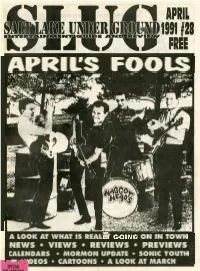

April's Fools

APRIL'S FOOLS ' A LOOK AT WHAT IS REAL f ( i ON IN. TOWN NEWS VIEWS . REVIEWS PREVIEWS CALENDARS MORMON UPDATE SONIC YOUTH -"'DEOS CARTOONS A LOOK AT MARCH frlday, april5 $7 NOMEANSNO, vlcnms FAMILYI POWERSLAVI saturday, april 6 $5 an 1 1 piece ska bcnd from cdlfomb SPECKS witb SWlM HERSCHEL SWIM & sunday,aprll7 $5 from washln on d.c. m JAWBO%, THE STENCH wednesday, aprl10 KRWTOR, BLITZPEER, MMGOTH tMets $10raunch, hemmetal shoD I SUNDAY. APRIL 7 I INgTtD, REALITY, S- saturday. aprll $5 -1 - from bs aqdes, califomla HARUM SCAIUM, MAG&EADS,;~ monday. aprlll5 free 4-8. MAtERldl ISSUE, IDAHO SYNDROME wedn apri 17 $5 DO^ MEAN MAYBE, SPOT fiday. am 19 $4 STILL UFEI ALCOHOL DEATH saturday, april20 $4 SHADOWPLAY gooah TBA mday, 26 Ih. rlrdwuhr tour from a land N~AWDEATH, ~O~LESH;NOCTURNUS tickets $10 heavy metal shop, raunch MATERIAL ISSUE I -PRIL 15 I comina in mayP8 TFL, TREE PEOPLE, SLaM SUZANNE, ALL, UFT INSANE WARLOCK PINCHERS, MORE MONDAY, APRIL 29 I DEAR DICKHEADS k My fellow Americans, though:~eopledo jump around and just as innowtiwe, do your thing let and CLIJG ~~t of a to NW slam like they're at a punk show. otherf do theirs, you sounded almost as ENTEIWAINMENT man for hispoeitivereviewof SWIM Unfortunately in Utah, people seem kd as L.L. "Cwl Guy" Smith. If you. GUIIBE ANIB HERSCHELSWIMsdebutecassette. to think that if the music is fast, you are that serious, I imagine we will see I'mnotamemberofthebancljustan have to slam, but we're doing our you and your clan at The Specks on IMVIEW avid ska fan, and it's nice to know best to teach the kids to skank cor- Sahcr+nightgiwingskrmkin'Jessom. -

Under New Management Judge Takes Running of Troubled Senior Residence from Owner

Yo u r Neighborhood — Yo u r News® BrooklynPaper.com • (718) 260–2500 • Brooklyn, NY • ©2015 Serving Brownstone Brooklyn, Williamsburg & Greenpoint AWP/16 pages • Vol. 38, No. 19 • May 8–14, 2015 • FREE ‘THEY FAILED ALL OF US’ Traffi c deaths deserve more attention from cops and prosecutors, says husband of victim By Noah Hurowitz The Brooklyn Paper Police need to do a better job investigating drivers who mow down pedestrians, says the hus- band of a woman who was killed by an unlicensed — and possi- bly drunk — driver on a Clinton Hill street in 2011. The widower lashed out at the cops who bun- gled the examination of his wife’s death so badly her alleged killer was never brought to trial. Jake Stevens damned police on Sunday during a memorial ser- vice for Clara Heyworth at the site of her death at the age of 28, calling them out for not ensuring the driver who killed ever saw a Stephan Keegan day behind bars. (Left) Jake Stevens, husband of the late Clara Heyworth, “F--- the police,” Stevens said watches as road safety activists paint a memorial near while standing at the corner of where a car fatally struck her at Dekalb and Vanderbilt av- Dekalb and Vanderbilt avenues, enues in 2011. where Heyworth was run down as he watched helplessly. “There has creased regulations to hold killer criticized as a lack of investiga- not been, and there will never be, drivers accountable for their ac- tion of such deaths. An orga- ever, any justice for Clara.” tions. Activists painted a pair of nizer said they have shifted to The widower called on cops rose-studded angel wings on the making memorials less confron- to do a better job investigating pavement. -

Partyman by Title

Partyman by Title #1 Crush (SCK) (Musical) Sound Of Music - Garbage - (Musical) Sound Of Music (SF) (I Called Her) Tennessee (PH) (Parody) Unknown (Doo Wop) - Tim Dugger - That Thing (UKN) 007 (Shanty Town) (MRE) Alan Jackson (Who Says) You - Can't Have It All (CB) Desmond Decker & The Aces - Blue Oyster Cult (Don't Fear) The - '03 Bonnie & Clyde (MM) Reaper (DK) Jay-Z & Beyonce - Bon Jovi (You Want To) Make A - '03 Bonnie And Clyde (THM) Memory (THM) Jay-Z Ft. Beyonce Knowles - Bryan Adams (Everything I Do) I - 1 2 3 (TZ) Do It For You (SCK) (Spanish) El Simbolo - Carpenters (They Long To Be) - 1 Thing (THM) Close To You (DK) Amerie - Celine Dion (If There Was) Any - Other Way (SCK) 1, 2 Step (SCK) Cher (This Is) A Song For The - Ciara & Missy Elliott - Lonely (THM) 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) (CB) Clarence 'Frogman' Henry (I - Plain White T's - Don't Know Why) But I Do (MM) 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New (SF) Cutting Crew (I Just) Died In - Coolio - Your Arms (SCK) 1,000 Faces (CB) Dierks Bentley -I Hold On (Ask) - Randy Montana - Dolly Parton- Together You And I - (CB) 1+1 (CB) Elvis Presley (Now & Then) - Beyonce' - There's A Fool Such As I (SF) 10 Days Late (SCK) Elvis Presley (You're So Square) - Third Eye Blind - Baby I Don't Care (SCK) 100 Kilos De Barro (TZ) Gloriana (Kissed You) Good - (Spanish) Enrique Guzman - Night (PH) 100 Years (THM) Human League (Keep Feeling) - Five For Fighting - Fascination (SCK) 100% Pure Love (NT) Johnny Cash (Ghost) Riders In - The Sky (SCK) Crystal Waters - K.D. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

James Dean from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Log in / create account Article Discussion Read Edit View history Search James Dean From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page This article is about the actor. For other uses, see James Dean (disambiguation). Contents James Byron Dean (February 8, 1931 – September 30, 1955) Featured content was an American film actor.[1] He is a cultural icon, best James Dean Current events embodied in the title of his most celebrated film, Rebel Without Random article a Cause (1955), in which he starred as troubled Los Angeles Donate to Wikipedia teenager Jim Stark. The other two roles that defined his stardom were as loner Cal Trask in East of Eden (1955), and Interaction as the surly farmer, Jett Rink, in Giant (1956). Dean's enduring Help fame and popularity rests on his performances in only these About Wikipedia three films, all leading roles. His premature death in a car Community portal crash cemented his legendary status.[2] Recent changes Contact Wikipedia Dean was the first actor to receive a posthumous Academy Award nomination for Best Actor and remains the only actor to Toolbox have had two posthumous acting nominations. In 1999, the Print/export American Film Institute ranked Dean the 18th best male movie star on their AFI's 100 Years...100 Stars list.[3] Languages Contents [hide] Dean in 1955 اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ Aragonés 1 Early life Born James Byron Dean Bosanski 2 Acting career February 8, 1931 Български Marion, Indiana, U.S. open in browser customize free license pdfcrowd.com Български 2.1 East of Eden Marion, Indiana, U.S. Català 2.2 Rebel Without a Cause Died September 30, 1955 (aged 24) Česky 2.3 Giant Cholame, California, U.S. -

James Dean: Magnificent Failure

Gay San Francisco: Eyewitness Drummer 133 James Dean: Magnificent Failure Written in 1960 and revised in September 1961, this feature essay was published in Preview: The Family Entertainment Guide, June 1962. I. Author’s Eyewitness Historical-Context Introduction written July 29, 2007 II. The feature article as published in Preview: The Family Entertainment Guide, June 1962 III. Eyewitness Illustrations I. Author’s Eyewitness Historical-Context Introduction written July 29, 2007 Revealing the Iconography of Drummer: When James Dean Met Marlon Brando, Heath Ledger, and Jake Gyllenhaal Marlon Brando: “Stella!” James Dean: “You’re tearing me apart.” Jake Gyllenhaal to Heath Ledger: “I wish I knew how to quit you.” As soon as we teenagers invented and liberated our tortured selves in the pop culture of the deadly dull 1950s, my leather bomber jacket morphed in meaning from “play clothing” to teen symbol. I was swept up by the movie Blackboard Jungle (1955) and its theme song, Bill Haley’s “Rock around the Clock,” which was played every ten minutes on the radio because no other white rock-n-roll songs yet existed. At the same instant, I found my first lover in James Dean, in his jackets, his motorcycle, his face, his attitude, his verite. When he was killed at age twenty-four on September 30, 1955, I was sixteen, a junior in high school, and stricken with grief. Even though I was in the Catholic seminary and was a sexually pure boy, art and literature and movies cancelled my chances of being paro- chial. (In 2007, it is more difficult to come out as a progressive Catholic ©Jack Fritscher, Ph.D., All Rights Reserved—posted 05-05-2017 HOW TO LEGALLY QUOTE FROM THIS BOOK 134 Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. -

Merkitysten Verkko Faniuden Diskursseja Pop-Tähti Morrisseyta Käsittelevän Sivuston Keskusteluissa

Merkitysten verkko Faniuden diskursseja pop-tähti Morrisseyta käsittelevän sivuston keskusteluissa Antti Haavisto Musiikintutkimuksen pro gradu -tutkielma Viestintätieteiden tiedekunta Tampereen yliopisto Joulukuu 2017 TAMPEREEN YLIOPISTO Viestintätieteiden tiedekunta HAAVISTO, ANTTI: MERKITYSTEN VERKKO. Faniuden diskursseja pop-tähti Morrisseyta käsittelevän sivuston keskusteluissa. Pro gradu -tutkielma, 76 s. Musiikintutkimus Joulukuu 2017 Tarkastelen pro gradu -tutkielmassani pop-artisti Steven Morrisseyn faniyhteisön toimintaa tälle omistetulla fanisivustolla osoitteessa www.morrissey-solo.com. Pyrin selvittämään minkälaisia diskursseja sivuston keskustelufoorumilla käydyt keskustelut sisältävät ja millaisia faniuden kategorioita keskusteluissa on mahdollista havaita. Tämän lisäksi pohdin sitä, miten entistä interaktiivisemmaksi muuttuva mediaympäristö on vaikuttanut tähteyteen, fanien toimintaan ja faniuden käytäntöihin. Tutkimukseni pääasiallinen aineisto koostuu seitsemästä laajuudeltaan vaihtelevasta keskusteluketjusta fanisivuston keskustelufoorumilla. Olen kerännyt aineiston internet- etnografiana, jossa seurasin tämän faniyhteisön keskustelemisen tapoja ja käytänteitä osallistumatta kuitenkaan itse keskusteluun. Analysoin aineiston tekstipohjaisena diskurssianalyysina, erityisesti kategoria-analyysia työkaluna käyttäen. Tutkimani fanisivuston keskusteluissa on havaittavissa useita eri diskursseja ja faniuden kategorioita, jotka osittaisista päällekkäisyyksistä huolimatta poikkeavat toisistaan merkittävillä tavoilla. Erityisen -

Nibbler by Ken Urban

NIBBLER BY KEN URBAN DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. NIBBLER Copyright © 2017, Ken Urban All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of NIB- BLER is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation profes- sional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, elec- tronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for NIBBLER are controlled exclusively by Dra- matists Play Service, Inc., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No profes- sional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of Dramatists Play Service, Inc., and paying the requi- site fee. Inquiries concerning all other rights should be addressed to Abrams Artists Agency, 275 Seventh Avenue, 26th Floor, New York, NY 10001. -

19-267 Our Lady of Guadalupe School V. Morrissey-Berru (07/08/2020)

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2019 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus OUR LADY OF GUADALUPE SCHOOL v. MORRISSEY- BERRU CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT No. 19–267. Argued May 11, 2020—Decided July 8, 2020* The First Amendment protects the right of religious institutions “to de- cide for themselves, free from state interference, matters of church government as well as those of faith and doctrine.” Kedroff v. Saint Nicholas Cathedral of Russian Orthodox Church in North America, 344 U. S. 94, 116. Applying this principle, this Court held in Hosanna- Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. EEOC, 565 U. S. 171, that the First Amendment barred a court from entertaining an employment discrimination claim brought by an elementary school teacher, Cheryl Perich, against the religious school where she taught. Adopting the so-called “ministerial exception” to laws governing the employment relationship between a religious institution and certain key employees, the Court found relevant Perich’s title as a “Minister of Religion, Commissioned,” her educational training, and her respon- sibility to teach religion and participate with students in religious ac- tivities. Id., at 190–191. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Nos(Otros), Los Textual

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Nos(Otros), Los Textual Poch@s: Understanding Notions of Chicanx/Latinx Identities through the Digital Art of Rio Yañez A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Chicana and Chicano Studies by María Daniela Z. Jiménez 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Nos(Otros), Los Textual Poch@s: Understanding Notions of Chicanx/Latinx Identities through the Digital Art of Rio Yañez by María Daniela Z. Jiménez Master of Arts in Chicana and Chicano Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor María C. Pons, Co-Chair Professor Charlene Villaseñor Black, Co-Chair This thesis presents the concept of textual poch@ through Bay Area-based artist, Rio Yañez’s artwork. The textual poch@ is an individual who experiences marginalization and/or has to justify themselves for deviating from their society’s dominant narratives and cultural tastes. Their deviation results in their own interpretation and reconfiguration of their culture (usually associated with aspects of their identity, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, class, physical abilities) through a rasquache framework – in terms of making do with what they have to create something new. Through visual and textual analyses, I focus on two of Yañez’s digital art collections, Morrissey-inspired artwork and Japanese-influence portraiture series, as my case studies. In doing so, I demonstrate how these two collections push against essentialism and unfix Chicanx/Latinx identity as it is tied to dominant Chicanx/Latinx cultural practices and tastes. ii The thesis of María Daniela Z. Jiménez is approved. Genevieve G. -

ADAM and the ANTS Adam and the Ants Were Formed in 1977 in London, England

ADAM AND THE ANTS Adam and the Ants were formed in 1977 in London, England. They existed in two incarnations. One of which lasted from 1977 until 1982 known as The Ants. This was considered their Punk era. The second incarnation known as Adam and the Ants also featured Adam Ant on vocals, but the rest of the band changed quite frequently. This would mark their shift to new wave/post-punk. They would release ten studio albums and twenty-five singles. Their hits include Stand and Deliver, Antmusic, Antrap, Prince Charming, and Kings of the Wild Frontier. A large part of their identity was the uniform Adam Ant wore on stage that consisted of blue and gold material as well as his sophisticated and dramatic stage presence. Click the band name above. ECHO AND THE BUNNYMEN Formed in Liverpool, England in 1978 post-punk/new wave band Echo and the Bunnymen consisted of Ian McCulloch (vocals, guitar), Will Sergeant (guitar), Les Pattinson (bass), and Pete de Freitas (drums). They produced thirteen studio albums and thirty singles. Their debut album Crocodiles would make it to the top twenty list in the UK. Some of their hits include Killing Moon, Bring on the Dancing Horses, The Cutter, Rescue, Back of Love, and Lips Like Sugar. A very large part of their identity was silohuettes. Their music videos and album covers often included silohuettes of the band. They also have somewhat dark undertones to their music that are conveyed through the design. Click the band name above. THE CLASH Formed in London, England in 1976, The Clash were a punk rock group consisting of Joe Strummer (vocals, guitar), Mick Jones (vocals, guitar), Paul Simonon (bass), and Topper Headon (drums).