'Words Which Could Only Be Your Own': the Crossroad Between Lyrics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Call out Miutia in Pennsy Strike Pledges Continue To

VOL. U L, NO. 256. Philaddphia Strikere Picket Hosiery Mills PLEDGES CONTINUE CALL OUT MIUTIA n m F A T A L IN PENNSY STRIKE TO COME IN FROM TO H0]D DRIVER ALL OVER NATION Martial Law to Be Pro- ARREST THIRD MAN Yondi ffit by (^r Dmeu by daoM d ia Fayette Connty IN SYLLA MURDER RockriDe Wonian Tester- M EHCAN BEATEN Officials Busy Explaining ?A ere 15,000 Miners day Passes Away at Hos BY SrA M SB COPS Various Pbases ef die Have Defied Authorities. Stanley Kenefic Also Comes pital This Momiug. Program— Coal and Ante* from Stamford — Police Raymond Judd Stoutnar, 17, son Pl^debpbia Man (Sves Ifis mobiles Next to Be Taken lUrrlsburf, Pa., July 29—(AP)— of Mr. and Mrs. John Stoatnar of Governor Plnchot told early today Seek Fourth Suspect. 851 Tolland Turnpike died at 7:30 m Up— Monday Sled h r jna-tlal law will be proclaimed in Side of His Arrest this morning at the Manchester Me Fayette county, heart of the turbu strike there. morial hospital from injuries re dnstry WiD Disenss Code. lent coal strike area, with the ar New York, July 29.—(AP)— A Barcelona. ceived early yesterday afternoon rival of National Guard troops now third man from Stamford, Conn., enroute. when thrown from his bicycle when Three hundred state soldiers, was booked on a homicide charge to MAY REQUEST LOAN hit by an automobile driven by Mrs. New York, July 29—(AP) — The Washington, July 29.—(AP)— eoulpped with automatic rifles, day In the slaying of Dr. -

Sidvd504 Musicspectr

Music Spectrum Page 5 of 23 death: “Dear God, take him, take them, take anyone, the stillborn, the newborn, the NorthernBlue infirm, take anyone, take people from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, just spare me.” Most of us 95North Reco wouldn’t say it out loud, but Morrissey outs our true sinister thoughts that pass through Or Music our brains. Palm Pictures Parasol Planetary Gro The Smiths: Under Review, An Provident Lab Independent Critical Analysis Righteous Ba The traditional topics in any Smiths Rhino biography are all covered here: the band Rough Trade name, traditional four piece lineup, Runway Netw ambiguous nature of Morrissey’s Ryko Music sexuality, being a household name in the Salt Lady Re UK (but not the U.S.), “Suffer Little Sanctuary Re Children” (Moors murders), album sleeves, singles slump, role of Mike Joyce Sounds Fami and Andy Rourke, reluctance to do videos Special Ops M in MTV era, Craig Gannon, and the split. Team Clermo However, while some of the information Theory 8 Rec may not be new, because The Smiths: Telarc Under Review, An Independent Critical Analysis is a video documentary, it is a comforting Transmit Sou companion for any Smiths fan or seeker. TVT Records Unschooled Having never attended a Smiths Convention http://www.musicconventions.com/, and Vanguard Re having very few close friends who are Smiths fans, sitting and watching so many writers, Wampus Rec musicians, and people in the circle discuss what the Smiths meant and mean is like Warp Record discovering that you’re not alone. Others have also spent hours thinking about why this Wind-up Rec band affected them so much. -

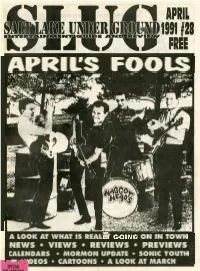

April's Fools

APRIL'S FOOLS ' A LOOK AT WHAT IS REAL f ( i ON IN. TOWN NEWS VIEWS . REVIEWS PREVIEWS CALENDARS MORMON UPDATE SONIC YOUTH -"'DEOS CARTOONS A LOOK AT MARCH frlday, april5 $7 NOMEANSNO, vlcnms FAMILYI POWERSLAVI saturday, april 6 $5 an 1 1 piece ska bcnd from cdlfomb SPECKS witb SWlM HERSCHEL SWIM & sunday,aprll7 $5 from washln on d.c. m JAWBO%, THE STENCH wednesday, aprl10 KRWTOR, BLITZPEER, MMGOTH tMets $10raunch, hemmetal shoD I SUNDAY. APRIL 7 I INgTtD, REALITY, S- saturday. aprll $5 -1 - from bs aqdes, califomla HARUM SCAIUM, MAG&EADS,;~ monday. aprlll5 free 4-8. MAtERldl ISSUE, IDAHO SYNDROME wedn apri 17 $5 DO^ MEAN MAYBE, SPOT fiday. am 19 $4 STILL UFEI ALCOHOL DEATH saturday, april20 $4 SHADOWPLAY gooah TBA mday, 26 Ih. rlrdwuhr tour from a land N~AWDEATH, ~O~LESH;NOCTURNUS tickets $10 heavy metal shop, raunch MATERIAL ISSUE I -PRIL 15 I comina in mayP8 TFL, TREE PEOPLE, SLaM SUZANNE, ALL, UFT INSANE WARLOCK PINCHERS, MORE MONDAY, APRIL 29 I DEAR DICKHEADS k My fellow Americans, though:~eopledo jump around and just as innowtiwe, do your thing let and CLIJG ~~t of a to NW slam like they're at a punk show. otherf do theirs, you sounded almost as ENTEIWAINMENT man for hispoeitivereviewof SWIM Unfortunately in Utah, people seem kd as L.L. "Cwl Guy" Smith. If you. GUIIBE ANIB HERSCHELSWIMsdebutecassette. to think that if the music is fast, you are that serious, I imagine we will see I'mnotamemberofthebancljustan have to slam, but we're doing our you and your clan at The Specks on IMVIEW avid ska fan, and it's nice to know best to teach the kids to skank cor- Sahcr+nightgiwingskrmkin'Jessom. -

Jeremyt Morrissey, Johnny Marr and the Smiths in London 1. Home to A

Author: JeremyT Morrissey, Johnny Marr and The Smiths in London 1. Home to a Mozzer, Regent's Park Terrace, Camden Mozzer lived on this street in the 90s... but which number? Notes: 2. Morrissey & Marr call time, 2 Farmer Street, London Johnny Marr called a Smiths meeting here to leave the band Notes: 3. Pop Video Morrissey Style, Lyndhurst Hall, Warden Road Sing Your Life was filmed here with help from Chrissie Hynde Notes: 4. Ridgeway House's Musical History, Runwick Lane, Farnham, Surrey Former recording studio of choice to the stars. Notes: 5. The Beeb rocks Out!, 2-22 Portland Place Home to legendary performances from the likes of Moz Notes: 6. Morrissey Lived Here..., Campden Hill Road, Kensington He did indeed, on this road, but can you tell us the number? Notes: 7. Moz and the Suedehead House, 32 Chester Square Mozzer seen here sometime in 1987/88 recording a superb video Notes: 8. A Post made famous by Morrissey, Tench Street / Reardon Street Mozzer and Post can be seen on the 'Bona Drag' album artwork Notes: www.shadyoldlady.com Page 1/2 9. Geoff Travis calls Johnny Marr, Blenheim Crescent, Marr & Rourke blagged their way in get The Smiths signed Notes: 10. Mary Poppins author lived here, 50 Smith Street, Chelsea The home and inspiration behind Mary Poppins. Notes: 11. Dirk Bogarde does Chelsea, 30 Royal Avenue, off King's Road Home to 'The Servant' starring Dirk Bogarde back in 1963 Notes: 12. Brixton Academy & The Smiths, 211 Stockwell Road The Smiths last ever gig took place here in 1986 Notes: www.shadyoldlady.com Page 2/2. -

America's Last Hope?

Wars on Christians Not Hitler’s Pope Empire or Umpire? Food Rights Fight ANDREW DORAN JOHN RODDEN & JOHN ROSSI ANDREW J. BACEVICH MARK NUGENT JULY/AUGUST 2013 ì ì#ììeìì ì ì # America’s Last Hope? ììeì ì ìeì ì ìì #ì ìeì ìì ! $9.99 US/Canada theamericanconservative.com Visit alphapub.com for FREE eBooks and Natural-law Essays We read that researchers have used new technology to fi nd proof behind biblical stories such as the Parting of the Red Sea and the Burning Bush. Our writing uses a biblical story with a deadly result that is still happening today. This biblical event is the creator’s command to Adam: “Of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat or you “Just found your site. will surely die.” Adam and Eve did eat the fruit of that tree, and for I was quite impressed disobeying the creator, they suffered much trouble and fi nally died. and look forward to Experience tells us that people worldwide are still acting on hours of enjoyment their judgments of good and evil. Now, consider what happens to and learning. Thanks.” millions of them every day? They die! It would follow that those - Frank whose behavior is based on their defi nitions of good and evil be- come subject to the creator’s warning, “or you will surely die.” We know that when people conform to creation’s laws of physics, right action always results. Children learn to walk and run by con- forming to all applicable natural laws. -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

Nibbler by Ken Urban

NIBBLER BY KEN URBAN DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. NIBBLER Copyright © 2017, Ken Urban All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of NIB- BLER is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation profes- sional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, elec- tronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for NIBBLER are controlled exclusively by Dra- matists Play Service, Inc., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No profes- sional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of Dramatists Play Service, Inc., and paying the requi- site fee. Inquiries concerning all other rights should be addressed to Abrams Artists Agency, 275 Seventh Avenue, 26th Floor, New York, NY 10001. -

19-267 Our Lady of Guadalupe School V. Morrissey-Berru (07/08/2020)

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2019 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus OUR LADY OF GUADALUPE SCHOOL v. MORRISSEY- BERRU CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT No. 19–267. Argued May 11, 2020—Decided July 8, 2020* The First Amendment protects the right of religious institutions “to de- cide for themselves, free from state interference, matters of church government as well as those of faith and doctrine.” Kedroff v. Saint Nicholas Cathedral of Russian Orthodox Church in North America, 344 U. S. 94, 116. Applying this principle, this Court held in Hosanna- Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. EEOC, 565 U. S. 171, that the First Amendment barred a court from entertaining an employment discrimination claim brought by an elementary school teacher, Cheryl Perich, against the religious school where she taught. Adopting the so-called “ministerial exception” to laws governing the employment relationship between a religious institution and certain key employees, the Court found relevant Perich’s title as a “Minister of Religion, Commissioned,” her educational training, and her respon- sibility to teach religion and participate with students in religious ac- tivities. Id., at 190–191. -

Reconstructing the Farm: Life Stories of Dutch Female Farmers

Student Anthropologist, Volume. 3, Number 1 Reconstructing the Farm: Life Stories of Dutch Female Farmers Marisa Turesky Brandeis University Abstract My research asks: what are the lived experiences of female farmers in a Dutch agricultural community like the Netherlands? Although popular culture portrays most female farmers as uneducated individuals of lower socioeconomic status, the six women who I interviewed in the Netherlands over the course of a short ethnographic research study present life stories that complicate this stereotype. In my conversations with female farm owners in the Netherlands, it emerged that a patriarchal paradigm appears to persist in industrial, conventional agriculture, seeming to encourage larger numbers of women to own more small-scale farms. While there is substantial existing research on rural women’s historical roles in farming, I add additional layers to this work, through my analysis of the personal experiences of a small sample of women farmers in the contemporary Netherlands. These women, who consider farming their lifestyle, discuss their inspiration, challenges, successes, and passion for their chosen occupation. In attempting to balance traditional roles of labor versus domesticity, these women actively challenge the gender binary through experiences in motherhood and business ownership. Keywords: Agriculture, Gender, Eco-feminism Introduction ! The role of Dutch women working on farms has shifted through the generations. Historically, Dutch women were key business partners in their husbands’ farming enterprises, but their roles and efforts were largely undervalued and under-recognized. Currently, women engaged in farming have responsibilities ranging from balancing work in the field with domestic duties inside of the home as part of a farming partnership, to complete ownership of the farm. -

Masteroppgave.Guro.Pdf (671.5Kb)

“Please Help The Cause Against Loneliness” The Importance of being a Morrissey fan Guro Flinterud Master Thesis in History of Culture Program for Culture and Ideas Studies Spring 2007 Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages, University of Oslo 2 Contents Chapter 1: Theorising Morrissey-fans……………………………………………………….5 Introduction..................................................................................................................................5 Who are The Smiths and Morrissey?...........................................................................................8 Overview of the field of fan studies……………………………………………………………11 Fans as source material………………………………………………………………………...14 Selected themes and how to reach them……………………………………………………….18 Speech genres and cultural spheres…………………………………………………………….23 Emotion and the expression of personal significance………………………………………….26 Narcissism, gender and individuality…………………………………………………………..29 Chapter 2: Fandom and love…………………………………………………………………35 The Fan and narcissism………………………………………………………………………...35 Self-reflection and the “new sort of hero”………………………………………………..........41 “Oh, I can’t help quoting you”; Morrissey in Odda……………………………………............45 The emotional dimension of music…………………………………………………………….50 Chapter 3: “I had never considered myself a normal teenager” Emotion, gender and outsiderness…………………………………………………………...56 The indie scene and masculinity………………………………………………………………..58 Morrissey fans contesting hegemonic masculinity……………………………………………..61 Non-gendered identification -

Maladjusted BC/Alberta Tour (Plus Vancouver) Final Report

maladjusted BC/Alberta Tour (plus Vancouver) Final Report David Diamond, Artistic/Managing Director Micheala Hiltergerke and Pierre Leichner in maladjusted. Photo: David Cooper “I just got home from seeing maladjusted. Thank you for making real theatre – theatre about and by people personally involved in large-impact, under-discussed, systematic experiences within our culture. Thank you for doing the impossible – for catalyzing deep and important conversation between strangers.” Kathryn Binnersley “maladjusted was a life changing performance!!’ Jenny Chen “maladjusted was so touching and well performed. 10 thumbs up!” Micha Souaid "I attended maladjusted and am forever changed." Kay Robinson “Thanks to Theatre for Living’s innovative and radical approach to the subject, maladjusted yields cheers along with tears.” Stuart Dreyden, Province Newspaper © Theatre for Living Society 323-350 East 2nd Ave Vancouver, BC Coast Salish Territory Canada V5T 4R8 [email protected] 2 The short version ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Theatre for Living Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 The evolution of and Forum Theatre ......................................................................................................... 4 Ticket Sales, the Voucher Program -

Adult Fiction

Adult Fiction Heroes of the Frontier The Woman in Cabin 10 Dave Eggers Ruth Ware When travel journalist Lo Blacklock is Josie is on the run with her invited on a boutique luxury cruise children. She's left her husband, around the Norwegian fjords, it seems her failing dental practice, and the like a dream job. But the trip takes a rest of her Ohio town to explore nightmarish turn when she wakes in Alaska in a rickety RV. the middle of the night to hear a body being thrown overboard. With his trademark insight, humor, and pathos, Dave Eggers explores Brit Ruth Ware has crafted her second this woman's truly heroic gripping, dark thriller in the Christie adventure, all the while exploring tradition. This page-turner toys with the concept of heroism in general. the classic plot of "the woman no one Brilliant, unpretentious, and highly would believe" with incredible language readable. and fun twists. Also a terrific, ~Alan’s and Leslie’s pick unabridged audiobook. ~Alan’s pick They May Not Mean To, But Barkskins They Do Annie Proulx Cathleen Schine Spanning hundreds of years, this When Joy Bergman's husband dies, ambitious work tells the often brutal her children are shocked that she story of the Canadian and New doesn't agree with their ideas for England lumber industry and all her. The book's title is from a those whom it enriched or displaced. Philip Larkin poem, and this funny and compassionate look at the Annie Proulx’s writing never ceases Bergman family brings Larkin's to thrill me.