Revamping the Metaphysics of Ethnobiological Classification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barking up the Same Tree: a Comparison of Ethnomedicine and Canine Ethnoveterinary Medicine Among the Aguaruna Kevin a Jernigan

Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine BioMed Central Research Open Access Barking up the same tree: a comparison of ethnomedicine and canine ethnoveterinary medicine among the Aguaruna Kevin A Jernigan Address: COPIAAN (Comité de Productores Indígenas Awajún de Alto Nieva), Bajo Cachiaco, Peru Email: Kevin A Jernigan - [email protected] Published: 10 November 2009 Received: 9 July 2009 Accepted: 10 November 2009 Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2009, 5:33 doi:10.1186/1746-4269-5-33 This article is available from: http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/5/1/33 © 2009 Jernigan; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: This work focuses on plant-based preparations that the Aguaruna Jivaro of Peru give to hunting dogs. Many plants are considered to improve dogs' sense of smell or stimulate them to hunt better, while others treat common illnesses that prevent dogs from hunting. This work places canine ethnoveterinary medicine within the larger context of Aguaruna ethnomedicine, by testing the following hypotheses: H1 -- Plants that the Aguaruna use to treat dogs will be the same plants that they use to treat people and H2 -- Plants that are used to treat both people and dogs will be used for the same illnesses in both cases. Methods: Structured interviews with nine key informants were carried out in 2007, in Aguaruna communities in the Peruvian department of Amazonas. -

A Comparative Study of Ethnobotanical Taxonomies: Swahili and Digo

A Comparative Study of Ethnobotanical Taxonomies: Swahili and Digo Steve Nicolle This paper explores how members of two East African language groups, with similar languages and cultures, classify the plant world. Differences primarily concern which parameters (e.g., size, uses, and longevity) determine how plant species are categorized. I show how linguistically similar classifications can obscure significant differences in folk botanical taxonomies. Introduction The early classic studies from which the present paper has developed began with the seminal ethnoscience work of the cognitive anthropologists Harold Conklin (1954, 1962), Charles Frake (1969), and Ward Goodenough (1957). Later influential ethnobiological taxonomic studies were done by Cecil Brown (1977, 1979), Terence Hays (1976), and especially by Brent Berlin and his co-authors (e.g., Berlin, Breedlove and Raven 1968, 1969, 1973, etc.) and peaking with Berlin's magnum opus (1992). Early methodologies for eliciting ethnobotanical folk taxonomies, now used as a standard, are found in Black (1969) and in Werner and Fenton's "card sorting" (1973); both methods were used in the present study. Later critics refined the endeavor of folk botanical classification as they encountered problems in "intra-cultural variability" among neighbors in the same speech community (e.g., Gal 1973, Pelto and Pelto 1975, Gardner 1976, Headland 1981, 1983, and several other papers in a special 1975 issue of American Ethnologist vol. 2, no. 1, titled "Intra-cultural Variability"). The present author found some of these problems of disagreements between informants as well. This brief study looks at the way plants are classified by speakers of two Northeast Coast Bantu languages, Swahili and Digo. -

Namechange Latinamericanca

University Council Athens, Georgia 30602 December 1, 2005 UN [VERSITY CURRICULUM COMMITTEE - 2005-2006 Dr. William Vencill, Chaii- Agricultural and Environmental Sciences - Dr. Amy B. Batal Arts and Sciences - Dr. Noel Fallows (Arts) Dr. lrwin S. Bel~istein(Sciences) Business - Dr. Stephen P. Baginslci Education - Dr. Elizabeth A. St. Pielre Envil-onnient and Design - Mr. Scott S. Weinlxrg Faniily and Cons~~nierSciences - Dr. Jan M. Hatlicote Foi-est Resources - Dr. David H. Newman Journalisn~and Mass Comm~mication- Dr. C. Ann Hollifield Law -Mr. David E. Shipley Pharmacy - Dr. Keith N. Herist Public and I~~ternatioiialAffairs - Dr. A~noldP. Fleischmann Public Health - Dr. Stuart Feldman Social Worlc - Dr. Patricia M. Reeves Veterinary Medicine - Dr. Scott A. Brown Graduate School - Dr. Richard E. Siegesmuiid Undei-graduate Student Representative - Ms. Amanila Sundal Grad~~ateStndent Representative - Mr. Todd Hawley Dear Collea,wes: The attached proposal from the Center for Latin A~nericanand Caribbean St~tdiesw~ll be all agentla item for the December 9, 2005, Full University Curriculuni Colnlnittee meetlng Proposal to Change the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies to a Latin Anicl-ican and Caribbean Studies Instit~~te Sincerely, Dr, William K. Vencill, Chair Unive~-sityCurriculum Committee cc: Dr. Arnett C. Mace, Jr Dl-. Delmer D. Dunu Executive Committee, Committee on Facilities, Committee on Intercollegiate Athletics, Committee on Statutes, Bylaws, and Committees, Committee on Student Affairs, Curriculum Committee, Educational -

An Ethnobotanical Anomaly: the Dearth of Binomial Specifics in a Folk Taxonomy of a Negrito Hunter-Gatherer Society in the Philippines

]. Ethnobiol. 3(2):109-120 December 1983 AN ETHNOBOTANICAL ANOMALY: THE DEARTH OF BINOMIAL SPECIFICS IN A FOLK TAXONOMY OF A NEGRITO HUNTER-GATHERER SOCIETY IN THE PHILIPPINES THOMAS N. HEADLAND Summer Institute of Linguistics Box 2270, Manila, Philippines ABSTRACT.-The Agta are a Negrito hunter-gatherer group in the Philippines. After a brief description of their culture, language, natural environment, and folk plant taxonomy, a comparison is made between that taxonomy and the universal model proposed by Brent Berlin. While the Agta data substantiate the Berlin model in most aspects, there is one salient area of conflict. The model proposes that specific biological taxa in any language are composed of binomials. It is argued here that the Agta case is an anomaly, in that their specific plant taxa are monomials. Four hypotheses are proposed as possible explanations for this anomaly. INTRODUCTION Certain cognitive anthropologists, particularly Brent Berlin and his associates, argue that in any ethnobiological taxonomy the specific taxa (those found at the third level of a taxonomy) are almost always binomial "secondary" lexemes.1 The suggestion is that this "binomiality principle" (Berlin 1978:20) may be a human universaL Most of the evidence published to date substantiates this hypothesis. Data gathered by the present author and his wife in the 1970s, however, provide a startling exception to the hypothesis. An analysis of an ethnobotanical taxonomy of the Agta Negritos found that of the sample of 143 specific taxa elicited from Agta infor mants, only five were binomials, and none of these were secondary lexemes. Further more, to the author's knowledge, no secondary biological lexemes were found to occur in the Agta language, except for the two varietal taxa mentioned in Note 3. -

How Folk Classification Interacts with Ethnoecological Knowledge: a Case Study from Chiapas, Mexico Aaron M

Journal of Ecological Anthropology Volume 14 Article 3 Issue 1 Volume 14, Issue 1 (2010) 2010 How Folk Classification Interacts with Ethnoecological Knowledge: A Case Study from Chiapas, Mexico Aaron M. Lampman Washington College Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jea Recommended Citation Lampman, Aaron M.. "How Folk Classification Interacts with Ethnoecological Knowledge: A Case Study from Chiapas, Mexico." Journal of Ecological Anthropology 14, no. 1 (2010): 39-51. Available at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jea/vol14/iss1/3 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Ecological Anthropology by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lampman / Tzeltal Ethnoecology How Folk Classification Interacts with Ethnoecological Knowledge: A Case Study from Chiapas, Mexico Aaron M. Lampman ABSTRACT Folk taxonomies play a role in expanding or contracting the larger domain of ethnoecological knowledge that influences when and how cultural groups use living things. This paper demonstrates that ethnomycological clas- sification is limited by utilitarian concerns and examines how Tzeltal Maya ethnoecological knowledge, although detailed and sophisticated, is heavily influenced by the structure of the folk classification system. Data were col- lected through 12 months of semi-structured and structured interviews, including freelists (n=100), mushroom collection with collaborators (n=5), open-ended interviewing (n=50), structured responses to photos (n=30), structured responses to mushroom specimens (n=15), and sentence frame substitutions (n=20). These interviews were focused on Tzeltal perceptions of mushroom ecology. -

Intro Matter

Journal of Ecological Anthropology Volume 5 Article 2 Issue 1 Volume 5, Issue 1 (2001) 1-1-2001 Intro Matter Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jea Recommended Citation . "Intro Matter." Journal of Ecological Anthropology 5, no. 1 (2001): 1-4. Available at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jea/vol5/iss1/2 This Front Matter is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Ecological Anthropology by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Ecological Anthropology VOLUME 5, 2001 SPECIAL ISSUE 2 Journal of Ecological Anthropology Vol. 5 2001 Editor’s Note This year’s special issue of the Journal of Ecological Anthropology is devoted to an exploratory essay on developing theoretical methodology in the study of human ecosystems. Its authors are aware of the fantastic hubris implied by this attempt. Luckily, such an ambitious project is necessarily a group effort and many have been involved from its inception. We now solicit our reader’s participation in the effort to develop methodology in ecological anthropology. A coherent theory of human ecosys- tems will only emerge out of public communication of ideas, creative contributions and critical exchange. This journal was created as a forum for advancing theory and practice in ecological anthro- pology by both conventional and unconventional means. We ask our readers to participate by communicating comments, critique and contributing ideas you may have for the essay “Method for Theory: A Prelude to Human Ecosystems.” Letters, emails, cartoons or graphic models will be published as Letters to the Editor in upcoming volumes of the JEA. -

Eugene S. Hunn Bibliography Anthropology Books and Museum

1 Eugene S. Hunn Bibliography Anthropology Books and Museum Catalogs Hunn, Eugene S. 1977. Tzeltal Folk Zoology: The Classification of Discontinuities in Nature. Academic Press, New York. Hunn, Eugene, with Constance Baltuck. 1981. A Photocopy Collection of Native Plants of Washington, 1981. Seattle: Thomas Burke Memorial Washington State Museum. Hunn, Eugene S. 1982. Birding in Seattle and King County. Seattle Audubon Society, Seattle, Washington. Williams, Nancy M., and Eugene S. Hunn, eds. 1982. Resource Managers: North American and Australian Hunter-Gatherers. American Association for the Advancement of Science Selected Symposia Series. Westview Press. Boulder, Colorado. Paperback edition published by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, Australia, 1986. Hunn, Eugene S. 1990. Nch'i-Wana, “The Big River”: Mid-Columbia Indians and Their Land. University of Washington Press, Seattle, Washington. Paperback edition, 1991. Governor's Writers Award, 1992. Second printing, 1995. Hunn, Eugene S., Darryll R. Johnson, Priscilla N. Russell, and Thomas F. Thornton. 2004. The Huna Tlingit People’s Traditional Use of gull Eggs and the Establishment of Glacier Bay National Park. Technical Report NPS D-121. Seattle, WA: National Park Service. Hunn, Eugene S. 2008. A Zapotec Natural History: Trees, Herbs, and Flowers, Birds, Beasts, and Bugs in the Life of San Juan Gbëë, with CD Rom. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. Association of American Publishers Prose Award for excellence in Archaeology & Anthropology, 2008. Johnson, Leslie Main, and Eugene S. Hunn, eds. 2010. Landscape Ethnoecology: Concepts of Biotic and Physical Space. Volume 14, Studies in Environmental Anthropology and Ethnobiology. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books. E. N. Anderson, Deborah M. -

From Ethical Codes to Ethics As Praxis: an Invitation

Perspectives Special Issue on Ethics in Ethnobiology From Ethical Codes to Ethics as Praxis: An Invitation Kelly Bannister1* 1POLIS Project on Ecological Governance, Centre for Global Studies, University of Victoria, Victoria, Canada. *[email protected] Abstract Ethical guidance for research involving Indigenous and traditional communities, cultural knowledge, and associated biological resources has evolved significantly over recent decades. Formal guidance for ethnobiological research has been thoughtfully articulated and codified in many helpful ways, including but by no means limited to the Code of Ethics of the International Society of Ethnobiology. We have witnessed a successful and necessary era of “research ethics codification” with ethical awareness raised, fora established for debate and policy development, and new tools evolving to assist us in treating one another as we agree we ought to within the research endeavor. Yet most of us still struggle with ethical dilemmas, conflicts, and differences that arise as part of the inevitable uncertainties and lived realities of our cross- cultural work. Is it time to ask what more (or what else) might we do, to lift the words on a page that describe how we should conduct ourselves, to connecting with the relational intention of those ethical principles and practices in concrete, meaningful ways? How might we discover ethics as relationship and practice while we necessarily aspire to follow adopted ethical codes as prescription? This paper brings together Willie Ermine’s concept of “ethical space” and Darrell Posey’s recognition of the spiritual values of biodiversity with a unique selection of insights from other fields of practice, such as intercultural communication, conflict resolution and martial arts, to invite a new conceptualization of research ethics in ethnobiology as ethical praxis. -

Nature and Society: Anthropological Perspectives

Nature and Society Nature and Society looks critically at the nature/society dichotomy—one of the central dogmas of western scholarship— and its place in human ecology and social theory. Rethinking the dualism means rethinking ecological anthropology and its notion of the relation between person and environment. The deeply entrenched biological and anthropological traditions which insist upon separating the two are challenged on both empirical and theoretical grounds. By focusing on a variety of perspectives, the contributors draw upon developments in social theory, biology, ethnobiology and sociology of science. They present an array of ethnographic case studies—from Amazonia, the Solomon Islands, Malaysia, the Moluccan Islands, rural communities in Japan and north-west Europe, urban Greece and laboratories of molecular biology and high-energy physics. The key focus of Nature and Society is the issue of the environment and its relations to humans. By inviting concern for sustainability, ethics, indigenous knowledge and the social context of science, this book will appeal to students of anthropology, human ecology and sociology. Philippe Descola is Directeur d’Etudes, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris, and member of the Laboratoire d’Anthropologie Sociale at the Collège de France. Gísli Pálsson is Professor of Anthropology at the University of Iceland, Reykjavik, and (formerly) Research Fellow at the Swedish Collegium for Advanced Study in the Social Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden. European Association of Social Anthropologists The European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA) was inaugurated in January 1989, in response to a widely felt need for a professional association which would represent social anthropologists in Europe and foster co-operation and interchange in teaching and research. -

Nahuatl Cultural Encyclopedia: Botany and Zoology, Balsas River, Guerrero

FAMSI © 2007: Jonathan D. Amith Nahuatl Cultural Encyclopedia: Botany and Zoology, Balsas River, Guerrero Research Year : 2004 Culture : Nahuatl Chronology : Colonial Location : Guerrero, México Site : Balsas River Valley Table of Contents Introduction Biological Inventory Textual Documentation: Audio and Transcription Collaborations Granting Agencies Scientific Institutions and Individual Academic Researchers Indigenous Communities, Associations, and Individuals Community Outreach Appendices List of Figures Sources Cited Submitted 03/07/2007 by: Jonathan D. Amith Director: México-North Program on Indigenous Languages Research Affiliate: Gettysburg College, Department of Sociology and Anthropology; Yale University; University of Chicago [email protected] Introduction Although extensive documentation of Aztec natural history was produced in the colonial period (e.g., de la Cruz, 1940; Hernández, 1959; Sahagún, 1963) there has been virtually no comprehensive research on modern Nahuatl ethnobiology. Attempts (dating to the nineteenth century) to identify in scientific nomenclature the plants described in the aforementioned colonial sources have relied on library studies, not fieldwork. There exists no comprehensive study of modern Nahuatl ethnozoology to shed light on the prehispanic culture in this domain. This situation can be compared to Mayan studies, which has been pioneering and intensive and has contributed greatly to our understanding of this culture, both before and after conquest (see Alcorn, 1984, Berlin and Berlin, 1996; Berlin, Breedlove, and Raven, 1974; Breedlove and Laughlin, 1993; Hunn, 1977; Orellana, 1987; Roys, 1931; to name but the most well known). The present FAMSI award was to begin to fill this lagunae in primary data and, in addition, for the production of an electronic and written corpus of Nahuatl language materials on the natural history (botany and zoology) of the Balsas River Valley in central México. -

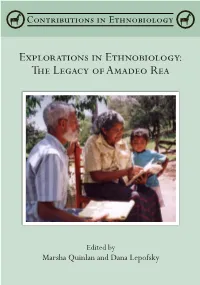

Explorations in Ethnobiology: the Legacy of Amadeo Rea

Explorations in Ethnobiology: The Legacy of Amadeo Rea Edited by Marsha Quinlan and Dana Lepofsky Explorations in Ethnobiology: The Legacy of Amadeo Rea Edited by Marsha Quinlan and Dana Lepofsky Copyright 2013 ISBN-10: 0988733013 ISBN-13: 978-0-9887330-1-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2012956081 Society of Ethnobiology Department of Geography University of North Texas 1155 Union Circle #305279 Denton, TX 76203-5017 Cover photo: Amadeo Rea discussing bird taxonomy with Mountain Pima Griselda Coronado Galaviz of El Encinal, Sonora, Mexico, July 2001. Photograph by Dr. Robert L. Nagell, used with permission. Contents Preface to Explorations in Ethnobiology: The Legacy of Amadeo Rea . i Dana Lepofsky and Marsha Quinlan 1 . Diversity and its Destruction: Comments on the Chapters . .1 Amadeo M. Rea 2 . Amadeo M . Rea and Ethnobiology in Arizona: Biography of Influences and Early Contributions of a Pioneering Ethnobiologist . .11 R. Roy Johnson and Kenneth J. Kingsley 3 . Ten Principles of Ethnobiology: An Interview with Amadeo Rea . .44 Dana Lepofsky and Kevin Feeney 4 . What Shapes Cognition? Traditional Sciences and Modern International Science . .60 E.N. Anderson 5 . Pre-Columbian Agaves: Living Plants Linking an Ancient Past in Arizona . .101 Wendy C. Hodgson 6 . The Paleobiolinguistics of Domesticated Squash (Cucurbita spp .) . .132 Cecil H. Brown, Eike Luedeling, Søren Wichmann, and Patience Epps 7 . The Wild, the Domesticated, and the Coyote-Tainted: The Trickster and the Tricked in Hunter-Gatherer versus Farmer Folklore . .162 Gary Paul Nabhan 8 . “Dog” as Life-Form . .178 Eugene S. Hunn 9 . The Kasaga’yu: An Ethno-Ornithology of the Cattail-Eater Northern Paiute People of Western Nevada . -

Careers in Ethnobotany

New Ethnoecology Position at University of Hawaii Notice sent in by Will McClatchey Dear SEB members, We are happy to announce that the University of Hawaii at Manoa is seeking to hire a new faculty member with expertise in the area of ethnoecology. The position is part of a larger effort to integrate the teaching and research activities of several departments into an ethnobiology program with certificates and degrees in ethnobotany, ethnobiology, ethnoecology, and ethnopharmacology. Current ethnobiology faculty include: Al Chock, Nina Etkin, Will McClatchey, Mark Merlin, and Lyndon Wester. Tentative closing date is September 15th, 2000. ETHNOECOLOGIST: The Department of Botany, College of Natural Sciences, invites applicants for an Assistant Professor, full-time, tenure track, nine-month position to begin January 3, 2001, pending position clearance and availability of funds. The department seeks an individual who will develop an outstanding research program and provide leadership in ethnoecology and related fields that emphasize studies of cultural interactions with botanical environments. Primary teaching responsibilities will include an introductory course in the undergraduate Ethnobiology curriculum, a lower division course in Botany or Biology, and an advanced course in the area of his/her research specialization. Secondarily, the individual will be expected to interact with the Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology program through teaching and/or research activities. Minimum qualifications are a Ph.D. in botany, an appropriate field of biological science or its equivalent; demonstrated teaching ability; demonstrated scholarly achievements. Desirable qualifications include postgraduate training and field-oriented research in Pacific or tropical ethnoecology, the ability to operate in a multi-cultural environment, and significant knowledge of, or interest in, traditional land use systems of the Pacific.