Pinochet Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Policy Toward Chile During the Cold War Centered on Maintaining Chile’S Economic and Political Stability

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses 2013 An Analysis Of U.S.- Economic Policy Toward Chile During The oldC War Frasier Esty Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Recommended Citation Esty, Frasier, "An Analysis Of U.S.- Economic Policy Toward Chile During The oC ld War" (2013). Honors Theses. 153. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/153 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. iv Acknowledgements I could not have finished this Thesis without the help of a variety of people. First and foremost, my advisor, Professor William Michael Schmidli proved to be an invaluable asset for me throughout the planning, writing, and revising processes. In addition, I could not have been able to complete the Honors Thesis project without the love and support of my family. Specifically, I dedicate this Thesis to my grandmother, Sally Murphy McDermott. Your consistent love and encouragement helped me throughout this process and I simply could not have done it without you. Thank you. -Frasier Esty v Table of Contents 1. Thesis Abstract 2. Introduction 3. Chapter 1: American Economic Policy Toward Chile Resulting In The Rise and Fall of Salvador Allende 4. Chapter 2: Pinochet’s Neoliberal Experiment 5. Chapter 3: The Reagan Years: A Changing Policy Toward Chile 6. Conclusion 7. Bibliography vi Abstract This examination of U.S. -

La Vía Chilena Al Socialismo. 50 Años Después. Tomo I: Historia

La vía chilena al socialismo 50 años después Tomo I. Historia Austin Henry, Robert. La vía chilena al socialismo: 50 años después / Robert Austin Henry; Joana Salém Vasconcelos; Viviana Canibilo Ramírez; compilado por Austin Henry, Robert; Joana Salém Vasconcelos; Viviana Canibilo Ramírez. - 1a ed. - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires: CLACSO, 2020. Libro digital, PDF Archivo Digital: descarga ISBN 978-987-722-769-7 1. Historia. 2. Historia de Chile. I. Salém Vasconcelos, Joana. II. Canibilo Ramírez, Viviana. III. Título. CDD 983 La vía chilena al socialismo: 50 años después Vol. I / Kemy Oyarzún V. ... [et al.]; compilado por Robert Austin Henry; Joana Salém Vasconcelos; Viviana Canibilo Ramírez; prefacio de Faride Zerán; Marcelo Arredondo. - 1a ed. - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires : CLACSO, 2020. Libro digital, PDF Archivo Digital: descarga ISBN 978-987-722-770-3 1. Historia. 2. Historia de Chile. I. Oyarzún V., Kemy. II. Austin Henry, Robert, comp. III. Salém Vasconcelos, Joa- na, comp. IV. Canibilo Ramírez, Viviana, comp. V. Zerán, Faride, pref. VI. Arredondo, Marcelo, pref. CDD 983 Diseño y diagramación: Eleonora Silva Arte de tapa: Villy La vía chilena al socialismo 50 años después Tomo I. Historia Robert Austin Henry, Joana Salém Vasconcelos y Viviana Canibilo Ramírez (compilación) CLACSO Secretaría Ejecutiva Karina Batthyány - Secretaria Ejecutiva Nicolás Arata - Director de Formación y Producción Editorial Equipo Editorial María Fernanda Pampín - Directora Adjunta de Publicaciones Lucas Sablich - Coordinador Editorial María Leguizamón - Gestión Editorial Nicolás Sticotti - Fondo Editorial LIBRERÍA LATINOAMERICANA Y CARIBEÑA DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES CONOCIMIENTO ABIERTO, CONOCIMIENTO LIBRE Los libros de CLACSO pueden descargarse libremente en formato digital o adquirirse en versión impresa desde cualquier lugar del mundo ingresando a www.clacso.org.ar/libreria-latinoamericana VolveremosLa vía chilena y seremos al socialismo. -

Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty Of

Writing the Opposition: Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Brad T. Eidahl December 2017 © 2017 Brad T. Eidahl. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Writing the Opposition: Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile by BRAD T. EIDAHL has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Patrick M. Barr-Melej Professor of History Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT EIDAHL, BRAD T., Ph.D., December 2017, History Writing the Opposition: Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile Director of Dissertation: Patrick M. Barr-Melej This dissertation examines the struggle between Chile’s opposition press and the dictatorial regime of Augusto Pinochet Ugarte (1973-1990). It argues that due to Chile’s tradition of a pluralistic press and other factors, and in bids to strengthen the regime’s legitimacy, Pinochet and his top officials periodically demonstrated considerable flexibility in terms of the opposition media’s ability to publish and distribute its products. However, the regime, when sensing that its grip on power was slipping, reverted to repressive measures in its dealings with opposition-media outlets. Meanwhile, opposition journalists challenged the very legitimacy Pinochet sought and further widened the scope of acceptable opposition under difficult circumstances. Ultimately, such resistance contributed to Pinochet’s defeat in the 1988 plebiscite, initiating the return of democracy. -

The United States, Eduardo Frei's Revolution in Liberty and The

The Gathering Storm: The United States, Eduardo Frei's Revolution in Liberty and the Polarization of Chilean Politics, 1964-1970 A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Sebastian Hurtado-Torres December 2016 © 2016 Sebastian Hurtado-Torres. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled The Gathering Storm: The United States, Eduardo Frei's Revolution in Liberty, and the Polarization of Chilean Politics, 1964-1970 by SEBASTIAN HURTADO-TORRES has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Patrick Barr-Melej Associate Professor of History Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT HURTADO-TORRES, SEBASTIAN, Ph.D., December 2016, History The Gathering Storm: The United States, Eduardo Frei’s Revolution in Liberty, and the Polarization of Chilean Politics, 1964-1970 Director of Dissertation: Patrick Barr-Melej This dissertation explores the involvement of the United States in Chilean politics between the presidential campaign of 1964 and Salvador Allende’s accession to the presidency in 1970. The main argument of this work is that the partnership between the Christian Democratic Party of Chile (PDC) and the United States in this period played a significant role in shaping Chilean politics and thus contributed to its growing polarization. The alliance between the PDC and the United States was based as much on their common views on communism as on their shared ideas about modernization and economic development. Furthermore, the U.S. Embassy in Santiago, headed by men strongly committed to the success of the Christian Democratic project, involved itself heavily in the inner workings of Chilean politics as an informal actor, unable to dictate terms but capable of exerting influence on local actors whose interests converged with those of the United States. -

Ciudadanos Imaginados: Historia Y Ficción En Las Narrativas Televisadas Durante El Bicentenario De La

Ciudadanos imaginados: historia y ficción en las narrativas televisadas durante el Bicentenario de la Independencia en Colombia, Chile y Argentina Mary Yaneth Oviedo Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures McGill University, Montreal November 2017 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Mary Yaneth Oviedo 2017 2 Tabla de contenido RESUMEN…............................................................................................................................................... 4 ABSTRACT………. .................................................................................................................................... 6 SOMMAIRE........ ........................................................................................................................................ 8 Agradecimientos.. ...................................................................................................................................... 10 Introducción……. ..................................................................................................................................... 11 Televisión, historia y ficción .................................................................................................................. 15 Televisión y melodrama ......................................................................................................................... 17 Capítulo 1. La Pola: La historia nacional hecha telenovela ........................................................... -

57C6d431037c3-Andres Aylwin Azocar V. Chile.Pdf

REPORT Nº 137/99 CASE 11,863 * ANDRES AYLWIN AZOCAR ET AL. CHILE December 27, 1999 I. SUMMA RY 1. On January 9, 1998, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (hereinafter the "Commission") received a petition against the Republic of Chile (hereinafter "the State," "the Chilean State," or "Chile") alleging violations of human rights set forth in the American Convention on Human Rights (hereinafter "the American Convention"), in particular political rights (Article 23) and the right to equal protection (Article 24), to the detriment of Chilean society, and in particular of the following persons identified as victims and petitioners in this case: Andrés Aylwin Azócar, Jaime Castillo Velasco, Roberto Garretón Merino, Alejandro González Poblete, Alejandro Hales Jamarne, Jorge Mera Figueroa, Hernán Montealegre Klenner, Manuel Sanhueza Cruz, Eugenio Velasco Letelier, Adolfo Veloso Figueroa, and Martita Woerner Tapia (hereinafter "the petitioners"). 2. The petitioners allege that the provision on senator-for-life (General Augusto Pinochet) and designated senators, found at Article 45 of the Chilean Constitution, thwarts the expression of popular sovereignty, implying that elections are no longer "genuine" in the terms required by Article 23(1)(b) of the American Convention, and that for the same reasons it violates the essence of the institutional framework of representative democracy, which is the basis and foundation for the entire human rights system now in force. Petitioners also allege that the designation of senators in the manner provided for under the new constitutional order in Chile constitutes an institution that violates the right to equality in voting, is inimical to popular sovereignty, and represents an obstacle making it practically impossible to change the non-democratic institutions established in the Chilean Constitution. -

SECOND OPEN LETTER to Arnold Harberger and Muton Friedman

SECOND OPEN LETTER to Arnold Harberger and MUton Friedman April 1976 II Milton Friedman and Arnold Harberger: You will recall that, following Harberger's first public visit to Chile after the military coup, I wrote you an open letter on August 6, 1974. After Harberger's second visit and the public announcement of Fried- man's intention to go to Chile as well, I wrote you a postscript on February 24, 1975. You will recall that in this open letter and postscript I began by reminis- cing about the genesis, during the mid-1950's, when I was your graduate student, of the "Chile program" in the Department of Economics at the University of Chicago, in which you trained the so-called "Chicago boys", who now inspire and execute the economic policy of the military Junta in Chile. I then went on to summarize the "rationale" of your and the Junta's policy by quoting Harberger's public declarations in Chile and by citing the Junta's official spokesmen and press. Finally, I examined with you the consequences, particularly for the people of Chile, of the applica- tion by military .force of this Chicago/Junta policy: political repression and torture, monopolization and sell-out to foreign capital, unemployment and starv- ation, declining health and increasing crime, all fos- tered by a calculated policy of political and economic genocide. 56 ECONOMIC GENOCIDE IN CHILE Since my last writing, worldwide condemnation of the Junta's policy has continued and increased, cul- minating with the condemnation of the Junta's violation of human rights by the United Nations General Assembly in a resolution approved by a vast majority including even the United States and with the Junta's condemnation even by the Human Rights Committee of the US-dominated reactionary Organiz- ation of American States. -

Víctor Osorio Reyes

Víctor Osorio Reyes 286 Ediciones Universidad Tecnológica Metropolitana Padre Felipe Gómez de Vidaurre (56-2) 787 77 50 Nº 1488, Santiago, Chile Metro La Moneda [email protected] Vicerrectoría de Transferencia Tecnológica y Extensión www.editorial.utem.cl www.utem.cl www.v!e.utem.cl Por las grandes Alamedas. Notas y crónicas políticas de Anibal Palma 1ra Edición, mayo de 2018 500 ejemplares © Ediciones Universidad Tecnológica Metropolitana ISBN: 978-956-9677-26-7 Editor y Compilador: © Víctor Osorio Reyes Colaboradora: Paulina Padilla Cerda Coordinadora y encargada de edición: Nicole Fuentes Soto Diseño, diagramación, portada y corrección de estilo: Ediciones Universidad Tecnológica Metropolitana Vicerrectoría de Transferencia Tecnológica y Extensión Fotografía página 204 extraída del libro “Salvador Allende Presidente de Chile. Discursos Escogidos 1970-1973” Está prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de este libro, su recopilación en un sistema informático y su transmisión en cualquier forma o medida (ya sea electrónica, mecánica, por fotocopia, registro o por otros medios) sin el previo permiso y por escrito de los titulares del copyright. Impresión: Imprex Santiago de Chile, mayo 2018 POR LAS GRANDES ALAMEDAS Reflexiones de Aníbal Palma Fourcade Víctor Osorio Reyes Editor y compilador Víctor Osorio Reyes ÍNDICE Presentación / 7 10. Nuevas farsas de la dictadura en Chile / 81 Prólogo / 9 11. No debe haber impunidad Introducción / 12 para los violadores de los Derechos Humano / 85 12. Carta al diario 1.Discurso frente a la La Tercera sobre dichos de Asamblea de la Organización Julio Durán / 90 de Estados Americanos / 22 13. De la Unidad Popular a la 2. Saludo del Ministro de lucha por el socialismo / 96 Educacion en el Día del Maestro / 33 14. -

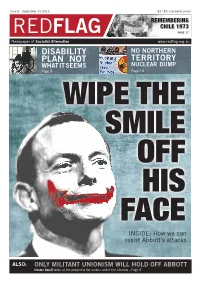

Red Flag Issue8 0.Pdf

Issue 8 - September 10 2013 $3 / $5 (solidarity price) REMEMBERING FLAG CHILE 1973 RED PAGE 17 Newspaper of Socialist Alternative www.redfl ag.org.au DISABILITY NO NORTHERN PLAN NOT TERRITORY WHAT IT SEEMS NUCLEAR DUMP Page 8 Page 13 WIPE THE SMILE OFF HIS FACE INSIDE: How we can resist Abbott’s attacks ALSO: ONLY MILITANT UNIONISM WILL HOLD OFF ABBOTT Jerome Small looks at the prospects for unions under the Liberals - Page 9 2 10 SEPTEMBER 2013 Newspaper of Socialist Alternative FLAG www.redfl ag.org.au RED CONTENTS EDITORIAL 3 How Labor let the bastards in Mick Armstrong analyses the election result. 4 Wipe the smile off Abbott’s face ALP wouldn’t stop Abbo , Diane Fieldes on what we need to do to fi ght back. now it’s up to the rest of us 5 The limits of the Greens’ leftism A lot of people woke up on Sunday leader (any leader) and wait for the 6 Where does real change come from? a er the election with a sore head. next election. Don’t reassess any And not just from drowning their policies, don’t look seriously about the Colleen Bolger makes the argument for getting organised. sorrows too determinedly the night deep crisis of Laborism that, having David confront a Goliath in yellow overalls before. The thought of Tony Abbo as developed for the last 30 years, is now prime minister is enough to make the at its most acute point. Jeremy Gibson reports on a community battling to keep McDonald’s soberest person’s head hurt. -

Narrow but Endlessly Deep: the Struggle for Memorialisation in Chile Since the Transition to Democracy

NARROW BUT ENDLESSLY DEEP THE STRUGGLE FOR MEMORIALISATION IN CHILE SINCE THE TRANSITION TO DEMOCRACY NARROW BUT ENDLESSLY DEEP THE STRUGGLE FOR MEMORIALISATION IN CHILE SINCE THE TRANSITION TO DEMOCRACY PETER READ & MARIVIC WYNDHAM Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Read, Peter, 1945- author. Title: Narrow but endlessly deep : the struggle for memorialisation in Chile since the transition to democracy / Peter Read ; Marivic Wyndham. ISBN: 9781760460211 (paperback) 9781760460228 (ebook) Subjects: Memorialization--Chile. Collective memory--Chile. Chile--Politics and government--1973-1988. Chile--Politics and government--1988- Chile--History--1988- Other Creators/Contributors: Wyndham, Marivic, author. Dewey Number: 983.066 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: The alarm clock, smashed at 14 minutes to 11, symbolises the anguish felt by Michele Drouilly Yurich over the unresolved disappearance of her sister Jacqueline in 1974. This edition © 2016 ANU Press I don’t care for adulation or so that strangers may weep. I sing for a far strip of country narrow but endlessly deep. No las lisonjas fugaces ni las famas extranjeras sino el canto de una lonja hasta el fondo de la tierra.1 1 Victor Jara, ‘Manifiesto’, tr. Bruce Springsteen,The Nation, 2013. -

Historia De La Ley N° 20.847

Historia de la Ley N° 20.847 Autoriza erigir un monumento en memoria del exministro, abogado y defensor de los Derechos Humanos señor Jaime Castillo Velasco en la comuna de Santiago Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile - www.bcn.cl/historiadelaley - documento generado el 30-Julio-2015 Nota Explicativa Esta Historia de Ley ha sido construida por la Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional a partir de la información disponible en sus archivos. Se han incluido los distintos documentos de la tramitación legislativa, ordenados conforme su ocurrencia en cada uno de los trámites del proceso de formación de la ley. Se han omitido documentos de mera o simple tramitación, que no proporcionan información relevante para efectos de la Historia de Ley. Para efectos de facilitar la revisión de la documentación de este archivo, se incorpora un índice. Al final del archivo se incorpora el texto de la norma aprobado conforme a la tramitación incluida en esta historia de ley. Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile - www.bcn.cl/historiadelaley - documento generado el 30-Julio-2015 ÍNDICE 1. Primer Trámite Constitucional: Cámara de Diputados .............................................................................. 3 1.1. Moción Parlamentaria ....................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2. Informe de Comisión de Cultura ........................................................................................................................ 6 1.3. Discusión en -

Friedrich Hayek and His Visits to Chile

Bruce Caldwell and Leonidas Montes Friedrich Hayek and his visits to Chile Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Caldwell, Bruce and Montes, Leonidas (2015) Friedrich Hayek and his visits to Chile. The Review of Austrian Economics, 28 (3). pp. 261-309. ISSN 0889-3047 DOI: 10.1007/s11138-014-0290-8 © 2014 Springer Science+Business Media New York This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/63318/ Available in LSE Research Online: August 2015 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Friedrich Hayek and his Visits to Chile By Bruce Caldwell, Duke University and Leonidas Montes, Adolfo Ibáñez University Abstract: F. A. Hayek took two trips to Chile, the first in 1977, the second in 1981. The visits were controversial. On the first trip he met with General Augusto Pinochet, who had led a coup that overthrew Salvador Allende in 1973.