State of Internet Freedom in Cameroon 2019 Mapping Trends in Government Internet Controls, 1999-2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voting for the Devil You Know: Understanding Electoral Behavior in Authoritarian Regimes

VOTING FOR THE DEVIL YOU KNOW: UNDERSTANDING ELECTORAL BEHAVIOR IN AUTHORITARIAN REGIMES A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Natalie Wenzell Letsa August 2017 © Natalie Wenzell Letsa 2017 VOTING FOR THE DEVIL YOU KNOW: UNDERSTANDING ELECTORAL BEHVAIOR IN AUTHORITARIAN REGIMES Natalie Wenzell Letsa, Ph. D. Cornell University 2017 In countries where elections are not free or fair, and one political party consistently dominates elections, why do citizens bother to vote? If voting cannot substantively affect the balance of power, why do millions of citizens continue to vote in these elections? Until now, most answers to this question have used macro-level spending and demographic data to argue that people vote because they expect a material reward, such as patronage or a direct transfer via vote-buying. This dissertation argues, however, that autocratic regimes have social and political cleavages that give rise to variation in partisanship, which in turn create different non-economic motivations for voting behavior. Citizens with higher levels of socioeconomic status have the resources to engage more actively in politics, and are thus more likely to associate with political parties, while citizens with lower levels of socioeconomic status are more likely to be nonpartisans. Partisans, however, are further split by their political proclivities; those that support the regime are more likely to be ruling party partisans, while partisans who mistrust the regime are more likely to support opposition parties. In turn, these three groups of citizens have different expressive and social reasons for voting. -

![Download Article [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1016/download-article-pdf-821016.webp)

Download Article [PDF]

60 JOURNAL OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS ELECTION MANAGEMENT IN CAMEROON Progress, Problems And Prospects Thaddeus Menang Thaddeus Menang is Advisor at the National Elections Observatory P O Box 13506, Yaoundé, Cameroon Tel.: + 237 771 55 71 e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Judged by internationally accepted norms and standards election management in Cameroon stands out as peculiar in more than one respect. Firstly, election management tasks are performed by a multiplicity of bodies and institutions, making it difficult to determine who is really responsible at each stage of the process. Secondly, the conduct of elections is governed by a battery of cross-referencing laws which election stakeholders often find hard to interpret and apply. The problems arising from this situation need to be and are, presently, being addressed within the framework of reforms that target, on the one hand, the adoption of a single, updated and enforceable electoral law and, on the other, the setting up of a viable election management body and the introduction of modern management methods. INTRODUCTION Whereas in the older and better-established democracies of the world election management has become a routine that, more often than not, produces satisfactory results, most of the budding democracies of the Third World are still grappling with the problem of determining which election management procedures are best suited to their specific national contexts. The older democracies themselves tend to differ one from the other, not only in terms of the electoral systems they have put in place but also as regards the specific election management procedures they have adopted. These variations raise the question of whether the management of elections in a democratic context can be said to be governed by a set of internationally accepted norms and standards. -

“These Killings Can Be Stopped” RIGHTS Government and Separatist Groups Abuses in Cameroon’S WATCH Anglophone Regions

HUMAN “These Killings Can Be Stopped” RIGHTS Government and Separatist Groups Abuses in Cameroon’s WATCH Anglophone Regions “These Killings Can Be Stopped” Abuses by Government and Separatist Groups in Cameroon’s Anglophone Regions Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36352 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36352 “These Killings Can Be Stopped” Abuses by Government and Separatist Groups in Cameroon’s Anglophone Regions Map .................................................................................................................................... i Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ............................................................................................................. -

Journal 3.1 Osaghae

74 JOURNAL OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS INDEPENDENT CANDIDATURE AND THE ELECTORAL PROCESS IN AFRICA Churchill Ewumbue-Monono Dr Churchill Ewumbue-Monono is Minister-Counsellor in the Cameroon Embassy in Russia UI Povarskaya, 40, PO Box 136, International Post, Moscow, Russian Federation Tel: +290 65 49/2900063; Fax: +290 6116 e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT This study reviews the participation of independent, non-partisan candidates in Africa. It examines the development of competitive elections on the continent between 1945 and 2005, a period which includes both decolonisation and democratic transition elections. It also focuses on the participation of independent candidates in these elections at both legislative and presidential levels. It further analyses the place of independent candidature in the continent’s future electoral processes. INTRODUCTION The concept of political independence, whether it refers to voters or to candidates, describes an individual’s non-attachment to and non-identification with a political party. Generally, voter-centred political independence takes the form of independent voters who, when registering to vote, do not declare their affiliation to a political party. There are also swing or floating voters, who vote independently for personalities or issues not for parties, and switch voters, who are registered voters with a history of crossing party lines. Furthermore, candidate-centred political independence may take the form of apolitical, independent, non-partisan candidates, as well as official and unofficial party candidates (Safire 1968, p 658). The recognition of political independence as a feature of the electoral process has led to the involvement of ‘independent personalities’ in managing election institutions. Examples are ‘independent judiciaries’, ‘independent electoral commissions’, and ‘independent election observers’. -

2018 EISA Annual Report

EISA ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Annual Report 2018 Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa i Annual Report 2018 iii EISA ANNUAL REPORT 2018 about eisa TYPE OF ORGANISATION EISA is an independent, non-profit non-partisan non- governmental organisation whose focus is elections, OUR VISION democracy and governance in Africa. AN AFRICAN CONTINENT WHERE DATE OF ESTABLISHMENT DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE, July 1996. HUMAN RIGHTS AND CITIZEN OUR PARTNERS PARTICIPATION ARE UPHELD IN A Electoral management bodies, political parties, civil society PEACEFUL ENVIRONMENT. organisations, local government structures, parliaments, and national, Pan-African organisations, Regional OUR MISSION Economic Communities and donors. EISA STRIVES FOR EXCELLENCE OUR APPROACH IN THE PROMOTION OF Through innovative and trust-based partnerships throughout the African continent and beyond, EISA CREDIBLE ELECTIONS, CITIZEN engages in mutually beneficial capacity reinforcement PARTICIPATION, AND THE activities aimed at enhancing all partners’ interventions in STRENGTHENING OF POLITICAL the areas of elections, democracy and governance. INSTITUTIONS FOR SUSTAINABLE OUR STRUCTURE DEMOCRACY IN AFRICA. EISA consists of a Board of Directors comprised of stakeholders from the African continent and beyond. The Board provides strategic leadership and upholds financial accountability and oversight. EISA has as its patron Sir Ketumile Masire, the former President of Botswana. The Executive Director is supported by an Operations Director and Finance and Administration Department. EISA's focused programmes include: Elections and Political Processes Balloting and Electoral Services Governance Institutions and Processes Supporting Transitions and Electoral Processes Programme In 2018 EISA had 7 field offices, namely, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Madagascar, Mali, Mozambique, Somalia, and Zimbabwe and a Central Africa regional office (Gabon). -

Post-Conflict Elections”

POST-CONFLICT ELECTION TIMING PROJECT† ELECTION SOURCEBOOK Dawn Brancati Washington University in St. Louis Jack L. Snyder Columbia University †Data are used in: “Time To Kill: The Impact of Election Timing on Post-Conflict Stability”; “Rushing to the Polls: The Causes of Early Post-conflict Elections” 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. ELECTION CODING RULES 01 II. ELECTION DATA RELIABILITY NOTES 04 III. NATIONAL ELECTION CODING SOURCES 05 IV. SUBNATIONAL ELECTION CODING SOURCES 59 Alternative End Dates 103 References 107 3 ELECTION CODING RULES ALL ELECTIONS (1) Countries for which the civil war has resulted into two or more states that do not participate in joint elections are excluded. A country is considered a state when two major powers recognize it. Major powers are those countries that have a veto power on the Security Council: China, France, USSR/Russia, United Kingdom and the United States. As a result, the following countries, which experienced civil wars, are excluded from the analysis [The separate, internationally recognized states resulting from the war are in brackets]: • Cameroon (1960-1961) [France and French Cameroon]: British Cameroon gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1961, after the French controlled areas in 1960. • China (1946-1949): [People’s Republic of China and the Republic of China (Taiwan)] At the time, Taiwan was recognized by at least two major powers: United States (until the 1970s) and United Kingdom (until 1950), as was China. • Ethiopia (1974-1991) [Ethiopia and Eritrea] • France (1960-1961) [France -

The Democratic Challenge in Africa

The Democratic Challenge in Africa The Carter Center The Carter Center May, 1994 Introduction On May 13-14, 1994, a group of 32 scholars and practitioners took part in a seminar on Democratization in Africa at The Carter Center. This consultation was a sequel to two similar meetings held in February 1989 and March 1990. Discussion papers from those seminars have been published under the titles, Beyond Autocracy in Africa and African Governance in the 1990s. During the period 1990-94, the African Governance Program of The Carter Center moved from discussions and reflections to active involvement in the complex processes of renewed democratization in several African countries. These developments throughout Africa were also monitored and assessed in the publication, Africa Demos. The letter of invitation to the 1994 seminar called attention to the need for a new period of collective reflection because of "the severe difficulties encountered by several of these transitions." "The overriding concern," it was further stated, "will be to identify what could be done to help strengthen the pluralist democracies that have emerged during the past five years and what strategies may be needed to overcome the many obstacles that are now evident." A list of 12 questions was sent to each of the participants with a request that they identify which ones they wished to address in their discussion papers. As it turned out, the choice of topics could be conveniently grouped in six panels. Following the seminar, 19 of the participants revised their papers for publication in this volume, while an additional four scholars (John Harbeson, Goran Hyden, Timothy Longman, and Donald Rothchild), who had been unable to attend the meeting, still submitted papers for discussion and publication. -

Africa Update Leading the News

ML Strategies Update David Leiter, [email protected] Georgette Spanjich, [email protected] Katherine Fox, [email protected] ML Strategies, LLC Sarah Mamula, [email protected] 701 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, DC 20004 USA 202 296 3622 202 434 7400 fax FOLLOW US ON TWITTER: @MLStrategies www.mlstrategies.com JANUARY 15, 2015 Africa Update Leading the News West Africa Ebola Outbreak On January 8th, the United Nations (U.N.) World Health Organization (WHO) announced the most advanced Ebola vaccine candidate will enter Phase III clinical trials in West Africa in January and February 2015. If proven effective, the vaccine will be available for deployment just a few months later. Details on the announcement can be read here. On January 8th, the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) provided an update on Operation United Assistance, which has cost $385 million to date. The Pentagon announced that 450 U.S. military personnel are in the process of returning from deployments to West Africa to contain the Ebola virus. U.S. service members returning from Ebola-affected countries in Africa are currently in quarantine at the Army base in Baumholder, Germany, Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington, Joint Base Langley- Eustis, Virginia, and at Fort Hood and Fort Bliss in Texas. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) General Martin Dempsey will brief Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel later this month on recommendations related to the continuation of the quarantine policy. More information can be found here. On January 8th, the Department of State announced the U.S. Government has contributed $1 million to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) for a new project that will improve and streamline efforts to diagnose the Ebola virus in Africa. -

The Pseudo-Democrat's Dilemma: Why Election Observation Became an International Norm

THE PSEUDO- DEMOCRAT’S DILEMMA THE PSEUDO- DEMOCRAT’S DILEMMA WHY ELECTION OBSERVATION BECAME AN INTERNATIONAL NORM Susan D. Hyde CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS ITHACA AND LONDON Cornell University Press gratefully acknowledges receipt of a grant from the Whitney and Betty MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies at Yale University, which helped in the publication of this book. The book was also published with the assistance of the Frederick W. Hilles Publication Fund of Yale University. Copyright © 2011 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2011 by Cornell University Press Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hyde, Susan D. The pseudo-democrat’s dilemma : why election observation became an international norm / Susan D. Hyde. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-4966-6 (alk. paper) 1. Election monitoring. 2. Elections—Corrupt practices. 3. Democratization. 4. International relations. I. Title. JF1001.H93 2011 324.6'5—dc22 2010049865 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fi bers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. -

Introductory Statement

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON Paix –Travail – Patrie Peace – Work – Fatherland ---------- ----------- PRESS CONFERENCE INTRODUCTORY STATEMENT BY Mr. LAURENT ESSO MINISTER OF STATE, MINISTER OF JUSTICE, KEEPER OF THE SEALS ON CLAIMS BY ANGLOPHONE LAWYERS YAOUNDE, 30 MARCH 2017 Good afternoon, Dear Journalists, Friends of mine. Before beginning our discussion, let me introduce the personalities who are accompanying the Minister of Justice. - Pr Jacques FAME NDONGO, Minister of Higher Education whom you know very well; - Mr Michel Ange ANGOUING, Minister of Public Service and Administrative Reform; - Mr. Michel Ange ANGOUING is a Super scale Legal Officer; - Mr Alamine Ousmane MEY, Minister of Finance; - Mr Jean Pierre FOGUI, Minister Delegate to the Minister of Justice, Chairman of the Ad Hoc Committee in charge of examining and proposing solutions to the concerns relating to the functioning of the judiciary; - Mr George GWANMESIA, Secretary General of the Ministry of Justice, Member of the Ad Hoc Committee; - Madam Florence ARREY, Director of Judicial Professions in the Ministry of Justice; And of course your all time Friend - Mr Issa TCHIROMA BAKARY, Minister of Communication; Our discussion will focus on measures that the President of the Republic has instructed the Government to take in order to provide answers to the claims presented by some Lawyers regarding the functioning of the Judiciary. I would like to present my communication to you in French, the English version is available. At the end of the presentations, we will take 3 or 4 questions for those who would like to complete the information that we have provided you with. Ladies and Gentlemen, Dear Journalists, Friends of mine, In October 2016, some Anglophone lawyers took to the streets of the jurisdictions of the Courts of Appeal of the North West and South West Regions. -

REVUE QUOTIDIENNE DE LA PRESSE Édition Du 25/02/16

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON Paix – Travail – Patrie Peace – Work – Fatherland ********** ********** MINISTERE DU TRAVAIL MINISTRY OF LABOUR ET DE LA SECURITE SOCIALE AND SOCIAL SECURITY ********** ********** SECRETARIAT GENERAL SECRETARIAT GENERAL ********** ********** CELLULE DE LA COMMUNICATION COMMUNICATION UNIT ********** ********* N°_____________/MINTSS/SG/CC/CEA1/CEA2 Yaoundé, le_____________ REVUE QUOTIDIENNE DE LA PRESSE Édition du 25/02/16 « Bonjour Augustes Lecteurs ! » QUELQUES UNES DES JOURNAUX PARUS CE MATIN APPELS A LA CANDIDATURE DE PAUL BIYA : L’UNDP, le MDR, l’ANDP et le FSNC DANS L’EMBARRAS (L’œil du Sahel). CHEFS TRADITIONNELS, SYNDICALISTES, DIPLÔMES DE L’ENAM…LES APPELS INSOLITES (Le Jour). RDPC : ILS ONT TENU TÊTE A PAUL BIYA (Mutations). ASSEMBLEE GENERALE DES AVOCATS : LE DOSSIER BRÛLANT DES ANGLOPHONES (La Nouvelle Expression). PORT AUTONOME DE DOUALA : LA LISTE DES 10 HAUTS CADRES CONVOQUÉS AU CONSUPE (Quotidien Emergence). OPERATION EPERVIER : GERVAIS MENDO ZE RECLAME 23 MILLIONS A LA CRTV (Le Quotidien de l’Economie). OPERATION EPERVIER : NKOTTO EMANE AVALE 9 MILLIARDS EN 5 ANS (La Météo). FERMETURE DE L’AEROPORT DE DOUALA : NSIMALEN PREND LE RELAIS (Cameroon Tribune). IBRAHIM MBOMBO NJOYA : LE MONARQUE QUI DEFIE LE PRINCE (Le Messager). COMMERCE INTRA-REGIONAL : L’AFRIQUE CENTRALE AU BAS DE L’ECHELLE (Le Quotidien de L’Economie). CACAO : TELCAR COCOA ET OLAM DOMINENT LES EXPORTATIONS (La Voix du Paysan). ELECTION A LA PRESIDENCE DE LA FIFA : TOMBI A ROKO SIDIKI ELECTEUR (Le Messager). DEVELOPPEMENT DE QUELQUES TITRES : POLITIQUE : APPELS À LA CANDIDATURE DE PAUL BIYA : L’UNDP, LE MDR, L’ANDP ET LE FSNC DANS L’EMBARRAS L’ŒIL DU SAHEL : Depuis quelques semaines, des motions et autres déclarations invitant le chef de l’Etat, par ailleurs président national du Rassemblement démocratique du peuple camerounais (RDPC), à se présenter lors du prochain scrutin présidentiel fusent de toutes parts à travers la République. -

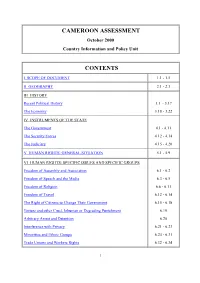

Cameroon Version 4 Clean#2

CAMEROON ASSESSMENT October 2000 Country Information and Policy Unit CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 II GEOGRAPHY 2.1 - 2.3 III HISTORY Recent Political History 3.1 - 3.17 The Economy 3.18 - 3.22 IV INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE The Government 4.1 - 4.11 The Security Forces 4.12 - 4.14 The Judiciary 4.15 - 4.20 V HUMAN RIGHTS: GENERAL SITUATION 5.1 - 5.9 VI HUMAN RIGHTS: SPECIFIC ISSUES AND SPECIFIC GROUPS Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.1 - 6.2 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.3 - 6.5 Freedom of Religion 6.6 - 6.11 Freedom of Travel 6.12 - 6.14 The Right of Citizens to Change Their Government 6.15 - 6.18 Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Punishment 6.19 Arbitrary Arrest and Detention 6.20 Interference with Privacy 6.21 - 6.23 Minorities and Ethnic Groups 6.24 - 6.31 Trade Unions and Workers Rights 6.32 - 6.34 1 Human Rights Groups 6.35 - 6.36 Women 6.36 - 6.41 Children 6.42 - 6.45 Treatment of Refugees 6.46 - 6.48 ANNEX A: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS Pages 19 - 22 ANNEX B: PROMINENT PEOPLE Page 23 ANNEX C: CHRONOLOGY Pages 24 - 27 ANNEX D: BIBLIOGRAPHY Pages 28 - 29 I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a variety of sources. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum determination process.