Daniel Libeskind and Turkish Architects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Introduction to Architectural Theory Is the First Critical History of a Ma Architectural Thought Over the Last Forty Years

a ND M a LLGR G OOD An Introduction to Architectural Theory is the first critical history of a ma architectural thought over the last forty years. Beginning with the VE cataclysmic social and political events of 1968, the authors survey N the criticisms of high modernism and its abiding evolution, the AN INTRODUCT rise of postmodern and poststructural theory, traditionalism, New Urbanism, critical regionalism, deconstruction, parametric design, minimalism, phenomenology, sustainability, and the implications of AN INTRODUCTiON TO new technologies for design. With a sharp and lively text, Mallgrave and Goodman explore issues in depth but not to the extent that they become inaccessible to beginning students. ARCHITECTURaL THEORY i HaRRY FRaNCiS MaLLGRaVE is a professor of architecture at Illinois Institute of ON TO 1968 TO THE PRESENT Technology, and has enjoyed a distinguished career as an award-winning scholar, translator, and editor. His most recent publications include Modern Architectural HaRRY FRaNCiS MaLLGRaVE aND DaViD GOODmaN Theory: A Historical Survey, 1673–1968 (2005), the two volumes of Architectural ARCHITECTUR Theory: An Anthology from Vitruvius to 2005 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2005–8, volume 2 with co-editor Christina Contandriopoulos), and The Architect’s Brain: Neuroscience, Creativity, and Architecture (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010). DaViD GOODmaN is Studio Associate Professor of Architecture at Illinois Institute of Technology and is co-principal of R+D Studio. He has also taught architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design and at Boston Architectural College. His work has appeared in the journal Log, in the anthology Chicago Architecture: Histories, Revisions, Alternatives, and in the Northwestern University Press publication Walter Netsch: A Critical Appreciation and Sourcebook. -

CS Global Shortlist 2011

SHORTLISTED NOMINEES FOR 2011 COMMERCIAL / MIXED USE BUILT COMMERCIAL / MIXED USE FUTURE Capital Gate - RMJM- Robert Matthew, Johnson-Marshall & Partners Fusionopolis 4 - Andrew Bromberg of Aedas Ltd Globevill Marketing - Office architectureRED Pazhou Exhibition Complex - Andrew Bromberg of Aedas Ltd Al Bidda Tower - GHD Global Pty Ltd King Abdullah Financial District Project 5.05 - Sudhir Jambhekar, FXFOWLE Rolex Tower - Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP Future of The Past - Md. Rafiq Azam, SHATOTTO architecture for green living Asmacati Shopping and Meeting Point - Melkan Gürsel & Murat Tabanlioglu Shijiazhuang International Convention & Exhibition Center - Nik Karalis, Woods Bagot COMMUNITY BUILT COMMUNITY FUTURE International Management Institute - Abin Chaudhuri - ABIN DESIGN STUDIO Sanjay Puri - Sanjay Puri Architects Pvt Ltd Run Run Shaw Creative Media Centre - Leigh & Orange Limited The Red Sea Institute for Cinematic Arts - Khalid Nahhas - Symbiosis Designs Ltd. Sipopo Congress Center - Melkan Gürsel & Murat Tabanlioglu - Tabanlıoğlu Architects Federal National Council Building Jason Burnside / Ehrlich Architects GAJ Utilisation of Leftover Space underneath a Flyover - BARRIE HO Architecture Interiors Ltd. Dubai Mosque - Fariborz Hatam of Aedas Ltd Ankara Arena Multi Functional Sports Hall - Kerem Yazgan , Yazgan Design Architecture Diplomatic Quarter, Celebration Hall - Godwin Austen Johnson LEISURE BUILT LEISURE FUTURE Al Shaqab Equestrian Academy - Leigh & Orange Limited Eastern Mangrove - Hyder Consulting Middle East Limited -

Vitra Worldwide References

WOR LDWIDE REFERENCES Building Products Propelled by a vision of smart and sustainable living for people of every age, ability and cultural background, the Eczacıbaşı Building Products Division is supported by its multi- brand, multiple manufacturing site and multi-market growth strategy. Pioneer of modern, high quality and healthy living Production Power In addition to five production facilities in Turkey, the Building Products Division has seven The Eczacıbaşı Group manufacturing sites located in major international markets including France, Germany Founded in 1942, Eczacıbaşı is a leading Turkish industrial group with 39 companies, over and Russia. The Division is the majority shareholder of V&B Fliesen GmbH, the former 11,600 employees and a combined net turnover in 2018 of TL 8.8 billion. tile division of Villeroy & Boch AG and Burgbad AG, the leader of the European luxury bathroom furniture market. Core Sectors Eczacıbaşı’s core sectors are building products, consumer products and healthcare. The Group is also active in information technology, natural resources and property development. Sustainable Approach The Eczacıbaşı Group embraces a holistic approach to sustainability that aims to achieve a balance between the needs of the business world and society – both in the present and future – and the sustainability of natural resources. Eczacıbaşı group has developed a road Social Responsibility map that takes into account not only the UN Sustainable Development Goals and global The Eczacıbaşı Group has founded and continuously supported numerous initiatives to risk, but also the challanges unique to Turkey. advance culture and the arts, scientific and public policy research, high quality education, and women in sports. -

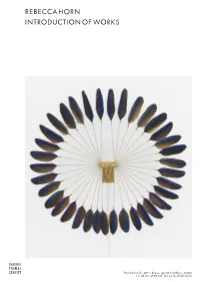

Rebecca Horn Introduction of Works

REBECCA HORN INTRODUCTION OF WORKS • Parrot Circle, 2011, brass, parrot feathers, motor t = 28 cm, Ø 67 cm | d = 11 in, Ø 26 1/3 in Since the early 1970s, Rebecca Horn (born 1944 in Michelstadt, Germany) has developed an autonomous, internationally renowned position beyond all conceptual, minimalist trends. Her work ranges from sculptural en- vironments, installations and drawings to video and performance and manifests abundance, theatricality, sensuality, poetry, feminism and body art. While she mainly explored the relationship between body and space in her early performances, that she explored the relationship between body and space, the human body was replaced by kinetic sculptures in her later work. The element of physical danger is a lasting topic that pervades the artist’s entire oeuvre. Thus, her Peacock Machine—the artist’s contribu- tion to documenta 7 in 1982—has been called a martial work of art. The monumental wheel expands slowly, but instead of feathers, its metal keels are adorned with weapon-like arrowheads. Having studied in Hamburg and London, Rebecca Horn herself taught at the University of the Arts in Berlin for almost two decades beginning in 1989. In 1972 she was the youngest artist to be invited by curator Harald Szeemann to present her work in documenta 5. Her work was later also included in documenta 6 (1977), 7 (1982) and 9 (1992) as well as in the Venice Biennale (1980; 1986; 1997), the Sydney Biennale (1982; 1988) and as part of Skulptur Projekte Münster (1997). Throughout her career she has received numerous awards, including Kunstpreis der Böttcherstraße (1979), Arnold-Bode-Preis (1986), Carnegie Prize (1988), Kaiserring der Stadt Goslar (1992), ZKM Karlsruhe Medienkunstpreis (1992), Praemium Imperiale Tokyo (2010), Pour le Mérite for Sciences and the Arts (2016) and, most recently, the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize (2017). -

Suburbanization Historic Context and Survey Methodology

INTRODUCTION The geographical area for this project is Maryland’s 42-mile section of the I-95/I- 495 Capital Beltway. The historic context was developed for applicability in the broad area encompassed within the Beltway. The survey of historic resources was applied to a more limited corridor along I-495, where resources abutting the Beltway ranged from neighborhoods of simple Cape Cods to large-scale Colonial Revival neighborhoods. The process of preparing this Suburbanization Context consisted of: • conducting an initial reconnaissance survey to establish the extant resources in the project area; • developing a history of suburbanization, including a study of community design in the suburbs and building patterns within them; • defining and delineating anticipated suburban property types; • developing a framework for evaluating their significance; • proposing a survey methodology tailored to these property types; • and conducting a survey and National Register evaluation of resources within the limited corridor along I-495. The historic context was planned and executed according to the following goals: • to briefly cover the trends which influenced suburbanization throughout the United States and to illustrate examples which highlight the trends; • to present more detail in statewide trends, which focused on Baltimore as the primary area of earliest and typical suburban growth within the state; • and, to focus at a more detailed level on the local suburbanization development trends in the Washington, D.C. suburbs, particularly the Maryland counties of Montgomery and Prince George’s. Although related to transportation routes such as railroad lines, trolley lines, and highways and freeways, the location and layout of Washington’s suburbs were influenced by the special nature of the Capital city and its dependence on a growing bureaucracy and not the typical urban industrial base. -

The Evolution of Architecture Faculty Organizational Culture at the University of Michigan Linda Mills

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations Graduate Capstone Projects 2018 The evolution of architecture faculty organizational culture at the University of Michigan Linda Mills Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.emich.edu/theses Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, and the Higher Education Administration Commons Recommended Citation Mills, Linda, "The ve olution of architecture faculty organizational culture at the University of Michigan" (2018). Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations. 933. https://commons.emich.edu/theses/933 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Graduate Capstone Projects at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: ARCHITECTURE FACULTY ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE The Evolution of Architecture Faculty Organizational Culture at the University of Michigan by Linda Mills Dissertation Eastern Michigan University Submitted to the Department of Leadership and Counseling Eastern Michigan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Educational Leadership Dissertation Committee: Ronald Flowers, Ed.D. Chair Jaclynn Tracy, Ph.D. Raul Leon, Ph.D. Russell Olwell, Ph.D. September 27, 2018 Ypsilanti, Michigan ARCHITECTURE FACULTY ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE ii Dedication This research is dedicated to all of the non-academic staff at the University of Michigan, at-will employees, who are working to support the work of faculty who operate with different norms, values and operating paradigms, protected by tenure, and unaware of the cognitive dissonance that exists between their operating worlds and ours. -

1968, Tendenza and Education in Aldo Rossi

1 Histories of PostWar Architecture 2 | 2018 | 1 Monument in Revolution: 1968, Tendenza and Education in Aldo Rossi Kenta Matsui PhD Candidate, The University of Tokyo (Japan), Department of Architecture, Graduate School of Engineering [email protected] MA Degree in History of Architecture at the Graduate school of the University of Tokyo. Research Fellowship for Young Scientists supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (2016-2018). His research focuses on the architectural theories of Aldo Rossi and other contemporary Italian architects in relation to the contexts of postwar Italy. ABSTRACT In the 1960’s, as Italian architectural schools faced student protests and forceful occupation attempts, Aldo Rossi tried to reform the schools through the idea of ‘tendency school’ shared with Carlo Aymonino, and to reconstruct architecture as discipline and theory. His theory has two aspects: urban analysis and architectural project. The former presents a dynamic conception of the temporal evolution of the city, as if echoing the restless social situation of the time; the latter centers on the logicality of architecture represented by monuments. This study explores the meaning of this dualism between urban analysis and architectural project as an intent for revolution, and in light of this, investigates the idea of ‘monument in revolution’. This study was supported by a research fund from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI, Grant Number JP16J05298). I would like to thank Bébio Amaro (Assistant Professor at Tianjin University, School of Architecture) for his aid in checking and revising the English text. Additionally, I would like to kindly acknowledge the many helpful suggestions and remarks provided by the anonymous reviewers, which have greatly contributed towards improving the overall quality and readability of this paper. -

Historic Context and Survey of Post-World War II Residential Architecture Boulder, Colorado FINAL

Historic Context and Survey of Post-World War II Residential Architecture Boulder, Colorado FINAL Prepared for the City of Boulder, Colorado In association with the State Historical Fund Colorado Historical Society By Jennifer Bryant and Carrie Schomig TEC Inc. April 2010 Historic Context and Survey of Post-World War II Residential Architecture, Boulder, Colorado FUNDING AND PARTICIPANTS Prepared for the Funded by State Historic Fund Grant City of Boulder Project #08-01-007 Community Planning and Sustainability Department Historic Preservation Program The Colorado Historical Society’s State Boulder, CO 80306 Historical Fund (SHF) was created by the 1990 James Hewat, Historic Preservation Planner Colorado constitutional amendment allowing 303-441-3207 limited gaming in the towns of Cripple Creek, Central City, and Black Hawk. The amendment Prepared by directs that a portion of the gaming tax Jennifer Bryant, M.A., Historian revenues be used to promote historic Carrie Schomig, M.Arh., Architectural Historian preservation throughout the state. Funds are TEC Inc. distributed through a competitive grant 1658 Cole Boulevard, Suite 190 process, and all projects must demonstrate Golden, Colorado 80401 strong public benefit and community support. The City of Boulder, Historic Preservation State Historical Fund Coordinator Program has been awarded a SHF grant to Elizabeth Blackwell develop a historic context related to the theme Historic Preservation Specialist of post-World War II residential architecture in State Historical Fund the City of Boulder. Colorado Historical Society State Survey Project Coordinator Mary Therese Anstey Historical and Architectural Survey Coordinator Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation Colorado Historical Society 225 East 16th Avenue, Suite 950 Denver, CO 80203 Cover: This circa (ca.) 1953-1956 photograph shows the Edgewood subdivision in north-central Boulder, looking northwest. -

The Patterns of Architecture/T3xture

THE PATTERNS OF ARCHITECTURE NIKOS A. SALINGAROS Published in Lynda Burke, Randy Sovich, and Craig Purcell, Editors: T3XTURE No. 3, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2016, pages 7-24. EDITORS’ INTRODUCTION Pattern theory has not as yet transformed architectural practice—despite the acclaim for A Pattern Language, 1 Christopher Alexander’s book, which introduced and substantiated the theory. However, it has generated a great amount of far-ranging, supportive scholarship. In this essay Nikos Salingaros expands the scope of the pattern types under consideration, and explicates some of the mathematical, scientific and humanistic justification for the pattern approach. The author also argues for the manifest superiority of the pattern approach to design over Modernist and contemporary theories of the last one hundred years. To a great extent Dr. Salingaros’s conviction rests on the process and goals of the pattern language method which have as their basis the fundamental realities of the natural world: the mathematics of nature (many that have been studied since the beginning of human history); the process of organic development; and the ideal structural environment for human activity. For Salingaros, Alexander, et al. aesthetics in Architecture derive from these principles rather than from notions of style or artistic inspiration. AUTHOR’S INTRODUCTION — KEY PATTERN CONCEPTS Pattern. A pattern is a discovered organization of space, and also a coherent merging of geometry with human actions. In common usage “pattern” has an expansive definition. In Architecture “pattern” often equates with “solution”. In any discussion of architectural pattern theory the word “pattern” itself is used repeatedly, often with reference to somewhat different concepts. -

Bbc Two Winter Highlights 2005 Bbc Two Winter Highlights 2005

BBC TWO WINTER HIGHLIGHTS 2005 BBC TWO WINTER HIGHLIGHTS 2005 COPYRIGHT NOTICE The material contained in this Press Pack bulletin is protected by copyright which is owned by the BBC and may not be reproduced or used other than in respect to BBC programmes. The Picture in this Press Pack bulletin may not be used without proir permission from the BBC. © BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION 2004 THE ROTTERS’ CLUB Adapted in four parts by Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais from Jonathan Coe’s novel,The Rotters’ Club is the story of three Birmingham families set against a backdrop of the class conflict and strike action – not to mention Blue Nun and prog-rock – that made up the socio-political landscape of Seventies Britain. The ensemble cast features new talent including Geoff Breton, Nicholas Shaw and Rasmus Hardiker, alongside established names Sarah Lancashire, Hugo Speer, Mark Williams and Kevin Doyle. Ben, Doug and Philip attend King William’s School, a middle-class institution that’s set to give them a start in life that their parents never had.Aspiring writer Ben lusts after “posh” Cicely Boyd, Doug flies the flag for socialism and prog-rock lover Philip is desperate to start his own band. Ben’s dad Colin is in middle management at Leyland’s Longbridge works, while Doug’s shop-steward father Bill is a dedicated trade union man. Philip’s bus driver dad Sam and housewife mum Barbara seem happy, but does Barbara want more from life? The Rotters’ Club is a tragi-comic blend of the personal and the political, taking in everything from strike action to the delights of first love.A tale not just of individuals but of an entire era, it is enriched by a real sense of life in the Seventies. -

9054 MAM MNM Gallery Notes

Museums for a New Millennium Concepts Projects Buildings October 3, 2003 – January 18, 2004 MUSEUMS FOR A NEW MILLENNIUM DOCUMENTS THE REMARKABLE SURGE IN MUSEUM BUILDING AND DEVELOPMENT AT THE TURN OF THE NEW MILLENNIUM. THROUGH MODELS, DRAWINGS, AND PHOTOGRAPHS, IT PRESENTS TWENTY-FIVE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT MUSEUM BUILDING PROJECTS FROM THE PAST TEN YEARS. THE FEATURED PROJECTS — ALL KEY WORKS BY RENOWNED ARCHITECTS — OFFER A PANORAMA OF INTERNATIONAL MUSEUM ARCHITECTURE AT THE OPENING OF THE 21ST CENTURY. Thanks to broad-based public support, MAM is currently in the initial planning phase of its own expansion with Museum Park, the City of Miami’s official urban redesign vision for Bicentennial Park. MAM’s expansion will provide Miami with a 21st-century art museum that will serve as a gathering place for cultural exchange, as well as an educational resource for the community, and a symbol of Miami’s role as a 21st-century city. In the last decade, Miami has quickly become known as the Gateway of the Americas. Despite this unique cultural and economic status, Miami remains the only major city in the United States without a world-class art museum. The Museum Park project realizes a key goal set by the community when MAM was established in 1996. Santiago Calatrava, Milwaukee Art Museum, 1994-2002, Milwaukee, At that time, MAM emerged with a mandate to create Wisconsin. View from the southwest. Photo: Jim Brozek a freestanding landmark building and sculpture park in a premiere, waterfront location. the former kings of France was opened to the public, the Louvre was a direct outcome of the French Revolution. -

Architecture and the Genius of Place Context

PRIMERS Context PRIMERS Context Architecture and the Genius of Place ERIC PARRY To A. A. P. and I. M. P. © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Registered office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www. wiley.com. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on- demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose.