Peter Carolin, Born 1936

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The British Library

PUBLIC SPACE AND THE ROLE OF THE ARCHITECT London Modernist Case Study Briefing (c. 2016 FABE Research Team, University of Westminster) THE BRITISH LIBRARY CONTENTS SUMMARY………………………………………………... .......... 3 1. BUILDING CHRONOLOGY……………………………......... 4 2. POLICY AND IDEOLOGY………………………………........ 7 3. AGENTS……………………………………………………….. 12 4. BRIEF…………………………………………………….......... 14 5. DESIGN…………………………………………………………16 6. MATERIALS/CONSTRUCTION/ENVIRONMENT 22 7. RECEPTION…………………………………………….......... 22 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………….……… 26 PROJECT INFORMATION Case Study: The British Library, 96 Euston Rd, London NW1 2DB Dates: 1962 - 1998 (final plan 1977, build 1982-1999, staggered opening November 1997- June 1999) Architects: Colin St John Wilson with M.J. Long, John Collier, John Honer, Douglas Lanham, Peter Carolin Client: The British Museum, then The British Library (following Act of Parliament 1972) Contractors: Phase 1A, Laing Management Contracting Ltd. Completion phase, McAlpine/Haden Joint Venture Financing: National government Site area: 112,643 m2 (building footprint is 3.1 hectares, on a site of 5 hectares) Tender price: £511 million. Budget overrun: £350 million 2 SUMMARY The British Library, the United Kingdom’s national library and one of six statutory legal depositories for published material, was designed and constructed over a 30-year period. It was designed by Colin St John Wilson (1922 – 2007) with his partner M J Long (1939 – ), and opened to the public in 1997. As well as a functioning research library, conference centre and exhibition space, the British Library is a national monument, listed Grade I in 2015. Brian Lang, Chief Executive of the British Library during the 1990s, described it as “the memory of the nation’, there to ‘serve education and learning, research, economic development and cultural enrichment.’1 The nucleus of what is now known as the British Library was, until 1972, known as the British Museum Library. -

St Cross Building, 612/24/10029 University of Oxford

St. Cross Building Conservation Plan May 2012 St. Cross Building, Oxford Conservation Plan, May 2012 1 Building No. 228 Oxford University Estates Services First draft March 2011 This draft May 2012 St. Cross Building, Oxford Conservation Plan, May 2012 2 THE ST. CROSS BUILDING, OXFORD CONSERVATION PLAN CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 7 1.1 Purpose of the Conservation Plan 7 1.2 Scope of the Conservation Plan 8 1.3 Existing Information 9 1.4 Methodology 9 1.5 Constraints 9 2 UNDERSTANDING THE SITE 13 2.1 History of the Site and University 13 2.2 Design, Construction, and Subsequent History of the St. Cross 14 Building 3 SIGNIFICANCE OF THE ST. CROSS BUILDING 21 3.1 Significance as part of the Holywell suburb, and the Central (City 21 and University) Conservation Area 3.2 Architectural Significance 24 3.3 Archaeological Significance 26 3.4 Significance as a major library and work space 27 3.5 Historical Significance 27 4 VULNERABILITIES 31 4.1 Access 31 4.2 Legibility 32 4.3 Maintenance 34 St. Cross Building, Oxford Conservation Plan, May 2012 3 4.4 Health and Safety 40 5 CONSERVATION POLICY 43 6 BIBLIOGRAPHY 51 7 APPENDICES 55 Appendix 1: Listed Building Description 55 Appendix 2: Conservation Area Description 57 Appendix 3: Chronology of the St. Cross Building 61 Appendix 4: Checklist of Significant Features 63 Appendix 5: Floor Plans 65 St. Cross Building, Oxford Conservation Plan, May 2012 4 St. Cross Building, Oxford Conservation Plan, May 2012 5 THIS PAGE HAS BEEN LEFT BLANK St. Cross Building, Oxford Conservation Plan, May 2012 6 1 INTRODUCTION The St. -

Suez 1956 24 Planning the Intervention 26 During the Intervention 35 After the Intervention 43 Musketeer Learning 55

Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd i 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iiii 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East Louise Kettle 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iiiiii 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Louise Kettle, 2018 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road, 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry, Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/1 3 Adobe Sabon by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain. A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 3795 0 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 3797 4 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 3798 1 (epub) The right of Louise Kettle to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iivv 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Contents Acknowledgements vii 1. Learning from History 1 Learning from History in Whitehall 3 Politicians Learning from History 8 Learning from the History of Military Interventions 9 How Do We Learn? 13 What is Learning from History? 15 Who Learns from History? 16 The Learning Process 18 Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East 21 2. -

DAW 2018 Brochure

DAW_2018_BROCHURE_COVER [3]_Layout 1 14/03/2018 15:49 Page 1 DORSET ART WEEKS 2018 DORSET ART FREE GUIDE OPEN STUDIOS, EXHIBITIONS, EVENTS 26 MAY –26 MAY 10 JUNE 26 MAY – 10 JUNE 2018 26 MAY – 10 JUNE 2018 OPEN STUDIOS, EXHIBITIONS, EVENTS DORSET VISUAL ARTS DORSET COTTAGES DORSET VISUAL ARTS DAW_2018_BROCHURE_COVER [3]_Layout 1 14/03/2018 15:49 Page 2 DORSET VISUAL ARTS DVA is a not for profit organisation and registered charity. It has a membership of some 300 artists, designers and makers living and practising in the county, some with national and international reputations. We are currently developing a number of opportunities for our members working across the spectrum of the visual arts with a focus on creative and professional development. Making Dorset www.dorsetvisualarts.org The driving ambition behind this grouping is to bring high quality design and making to new markets within and beyond Dorset. We aim to develop the group’s identity further to become recognised nationally and Dorset Art Weeks internationally. Membership of the OPEN STUDIOS group is by selection. EXHIBITIONS EVENTS DORSET DAW is an open studio event open to all artists practising in Dorset, regardless of DVA membership. VISUAL Produced by DVA, it is its biennial, Membership Groups flagship event. Reputedly the largest biennial open studios event in the ARTS INTERROGATING PROJECTS country. The event attracts around For those wanting to benefit from 125,000 studio visits. Visitors are interaction with other artists. The focus fascinated by seeing how artists work of group sessions is on creative and and the varied types of environment professional development. -

Plantlife—Annual Review 2013

Plantlife in numbers Patron: HRH The Prince of Wales Plantlife HQ targeted for meadow 14 Rollestone Street restoration under Salisbury SP1 1DX our new Save 01722 342730 [email protected] Our Magnificent Plantlife Scotland, Stirling Meadows scheme 01786 478509 [email protected] by Plantlife staff Plantlife Cymru, Cardiff and volunteers 02920 376193 [email protected] running the Virgin London Marathon www.plantlife.org.uk attended Plantlife created or restored as part of Scotland’s workshops, our Coronation Meadows project events, demonstration days, walks and talks We are Plantlife doing amazing Plantlife is the organisation that is speaking up for our wild flowers, work for Plantlife plants and fungi. From the open spaces of our nature reserves Plantlife is a charitable to the corridors of government, we’re here to raise their profile, company limited by guarantee, to celebrate their beauty, and to protect their future. aged from four to 90, company no. 3166339 Registered in England and Wales, Wild flowers and plants play a fundamental role for wildlife, and have contributed their own patchwork charity no. 1059559 their colour and character light up our landscapes. But without our to our Patchwork Meadow exhibition, Registered in Scotland, help, this priceless natural heritage is in danger of being lost. charity no. SC038951 which is touring Europe Join us in enjoying the very best that nature ISBN 978-1-910212-09-7 has to offer. September 2014 banned from sale designbyStudioAde.com after campaigning by Printed using -

To Revel in God's Sunshine

To Revel in God’s Sunshine The Story of RSM J C Lord MVO MBE Compiled by Richard Alford and Colleagues of RSM J C Lord © R ALFORD 1981 First Edition Published in 1981 Second Edition Published Electronically in 2013 Cover Pictures Front - Regimental Sergeant Major J C Lord in front of the Grand Entrance to the Old Building, Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. Rear - Army Core Values To Revel in God’s Sunshine The Story of the Army Career of the late Academy Sergeant Major J.C. Lord MVO MBE As related by former Recruits, Cadets, Comrades and Friends Compiled by Richard Alford (2nd Edition - Edited by Maj P.E. Fensome R IRISH and Lt Col (Retd) A.M.F. Jelf) John Lord firmly believed the words of Emerson: “Trust men and they will be true to you. Treat them greatly and they will show themselves great.” Dedicated to SOLDIERS SOLDIERS WHO TRAIN SOLDIERS SOLDIERS WHO LEAD SOLDIERS The circumstances of many contributors to this book will have changed during the course of research and publication, and apologies are extended for any out of date information given in relation to rank and appointment. i John Lord when Regimental Sergeant Major The Parachute Regiment Infantry Training Centre ii CONTENTS 2ND EDITION Introduction General Sir Peter Wall KCB CBE ADC Gen – CGS v Foreword WO1 A.J. Stokes COLDM GDS – AcSM R M A Sandhurst vi Editor’s Note Major P.E Fensome R IRISH vii To Revel in God’s Sunshine Introduction The Royal British Legion Annual Parade at R.M.A Sandhurst viii Chapter 1 The Grenadier Guards, Brighton Police Force 1 Chapter 2 Royal Military College, Sandhurst. -

THE PRINCE of WALES and the DUCHESS of CORNWALL Background Information for Media

THE PRINCE OF WALES AND THE DUCHESS OF CORNWALL Background Information for Media May 2019 Contents Biography .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Seventy Facts for Seventy Years ...................................................................................................... 4 Charities and Patronages ................................................................................................................. 7 Military Affiliations .......................................................................................................................... 8 The Duchess of Cornwall ............................................................................................................ 10 Biography ........................................................................................................................................ 10 Charities and Patronages ............................................................................................................... 10 Military Affiliations ........................................................................................................................ 13 A speech by HRH The Prince of Wales at the "Our Planet" premiere, Natural History Museum, London ...................................................................................................................................... 14 Address by HRH The Prince of Wales at a service to celebrate the contribution -

Zanussi, L'ultima Scommessa Visti in Libano E Somalia Loi E I Suoi Parà

18COM01A1806 18COM04A1806 FLOWPAGE ZALLCALL 11 21:26:01 06/17/97 ICOMMENTI l’Unità 17 Mercoledì 18 giugno 1997 INDUSTRIA UN’IMMAGINE DA... L’INTERVENTO Zanussi, Visti in Libano e Somalia l’ultima Loi e i suoi parà non erano scommessa una banda di violentatori LUIGI MARIUCCI MAURO MONTALI UTTI i sistemi maturi di rela- LI EPISODI di violenza av- mesiinSomaliaemièsempre zioni industriali si reggonosu venuti in Somalia sono parso (ma questo, ovviamente, tre pilastri: conflitto, con- semplicemente disgustosi. non conta molto) che i nostri sol- T trattazione, partecipazione. G Orrendo, non saprei quale dati tenessero un comportamen- In Italia invece il sistema è zoppo, altra parola usare, è lo stupro sulla to estremamente corretto. Co- poiché il tema della partecipazione ragazza. Spero che la magistratura munque, ero a Mogadiscio duran- è del tutto assente dalla scena delle vadafinoinfondocosìcomeilmini- te il periodo più «caldo» quando, relazioni industriali. Delle diverse stero della Difesa: quella gente ha cioè, furono uccisi, a freddo, i tre sperimentazioni succedutesi in ma- infangato l’esercito e il paese e me- soldati italiani durante un rastrel- teria non è restato pressoché nulla. rita, pertanto, se verranno appura- lamento d’armi nel tristemente Con buona pace dei rituali dibattiti te le responsabilità, una punizione famoso quartiere del Pastificio. in materia di attuazione dell’art. 46 esemplare. Che per una settimana fu perso. della Costituzione non si va infatti al Credo, però, che la brigata para- In quel periodo si consumò la rot- di là delle modeste pratiche di eser- cadutisti Folgore,nelsuocomples- tura con gli americani e con l’am- cizio dei diritti di informazione e so, sia una cosa ben diversa da miraglio Howe, il quale, essendo consultazione previsti dai contratti come è stata rappresentata in a capo della missione «Restore nazionali di categoria. -

Public Notice

Public notice Consolidation and Review of Traffic Management Orders for ‘Map-based’ Schedule Format The London Borough of Southwark (Charged-For Parking Places) (Map-based) Order 202* The London Borough of Southwark (Free Parking Places, Loading Places and Waiting, Loading and Stopping Restrictions) (Map-based) Order 202* 1. Southwark Council hereby GIVES NOTICE that it proposes to make the above Orders under sections 6, 45, 46, 49, 63 and 124 of and Part IV of Schedule 9 to the Road Traffic Regulation Act 19841, as amended. 2. The general effect of the Orders would be: (a) to consolidate the provisions of all existing Orders designating on-street charged-for parking places, free parking places, loading places and waiting, loading and stopping restrictions on streets in the London Borough of Southwark; (b) to update the terms and conditions for the use of on-street free parking places, loading places and waiting, loading and stopping restrictions as well as all on-street charged-for parking places set by those Orders. These would reflect the Council’s current parking policy in terms of eligibility for permits and applicable fees and charges, and any applicable exemptions; and (c) to provide for the use of a ‘map-based’ schedule, to be read in conjunction with the Orders, describing the location, type of the restriction, class of vehicle, the hours of operation and where applicable, the Controlled Parking Zone in which the parking places are located (and thereby the permit types to be displayed on or indicated in relation to vehicles left in parking places). NOTE: there would be no change to the existing layout, type or amount of provision of on- street charged-for parking places, on-street free parking places, loading places and waiting, loading and stopping restrictions, other than as detailed above, to the terms of use thereof (and any applicable fees and charges) as is currently published online by the Council, as a result of the making of these Orders. -

Pallant House Gallery

__ The Economic Contribution of Pallant House Gallery 16 June 2016 Contents 5. Economic Model ............................................................................... 20 5.1 Additionality Analysis .......................................................................... 21 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................... 3 5.2 Economic Multipliers ........................................................................... 23 1.1 Growing Organisation ........................................................................... 3 5.3 GVA and FTE Conversion .................................................................. 23 1.2 Dedicated Audience ............................................................................. 3 5.4 Economic Modelling Results ............................................................... 24 1.3 Overall Economic Impact ..................................................................... 3 5.4.1 Audience Analysis ............................................................................... 24 1.4 Expansion since 2008 .......................................................................... 4 5.4.2 Organisation Analysis ......................................................................... 25 2. Introduction ........................................................................................ 5 5.4.3 Overall Assessment ............................................................................ 25 2.1 Methodological Overview .................................................................... -

Contents the Royal Front Cover: Caption Highland Fusiliers to Come

The Journal of Contents The Royal Front Cover: caption Highland Fusiliers to come Battle Honours . 2 The Colonel of the Regiment’s Address . 3 Royal Regiment of Scotland Information Note – Issues 2-4 . 4 Editorial . 5 Calendar of Events . 6 Location of Serving Officers . 7 Location of Serving Volunteer Officers . 8 Letters to the Editor . 8 Book Reviews . 10 Obituaries . .12 Regimental Miscellany . 21 Associations and Clubs . 28 1st Battalion Notes . 31 Colour Section . 33 2006 Edition 52nd Lowland Regiment Notes . 76 Volume 30 The Army School of Bagpipe Music and Highland Drumming . 80 Editor: Army Cadet Force . 83 Major A L Mack Regimental Headquarters . 88 Assistant Editor: Regimental Recruiting Team . 89 Captain K Gurung MBE Location of Warrant Officers and Sergeants . 91 Regimental Headquarters Articles . 92 The Royal Highland Fusiliers 518 Sauchiehall Street Glasgow G2 3LW Telephone: 0141 332 5639/0961 Colonel-in-Chief HRH Prince Andrew, The Duke of York KCVO ADC Fax: 0141 353 1493 Colonel of the Regiment Major General W E B Loudon CBE E-mail: [email protected] Printed in Scotland by: Regular Units IAIN M. CROSBIE PRINTERS RHQ 518 Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow G2 3LW Beechfield Road, Willowyard Depot Infantry Training Centre Catterick Industrial Estate, Beith, Ayrshire 1st Battalion Salamanca Barracks, Cyprus, BFPO 53 KA15 1LN Editorial Matter and Illustrations: Territorial Army Units The 52nd Lowland Regiment, Walcheren Barracks, Crown Copyright 2006 122 Hotspur Street, Glasgow G20 8LQ The opinions expressed in the articles Allied Regiments Prince Alfred’s Guard (CF), PO Box 463, Port Elizabeth, of this Journal are those of the South Africa authors, and do not necessarily reflect the policy and views, official or The Royal Highland Fusiliers of Canada, Cambridge, otherwise, of the Regiment or the Ontario MoD. -

Manoscritti E Autografi

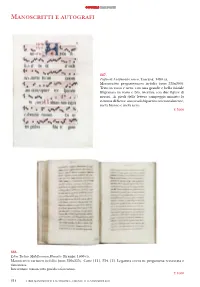

GONNELLI CASA D’ASTE GONNELLI CASA D’ASTE Manoscritti e autografi 887. Foglio di Antifonario senese. Toscana: 1480 ca. Manoscritto pergamenaceo in-folio (mm 535x390). Testo in rosso e nero, con una grande e bella iniziale filigranata in rosso e blu, istoriata con due figure di musici. Ai piedi della lettera campeggia miniato lo stemma di Siena: uno scudo bipartito orizzontalmente, metà bianco e metà nero. € 3600 888. Liber Tertius Maleficiorum Florentie. Firenze: 1600 ca. Manoscritto cartaceo in-folio (mm 320x225). Carte [11], 334, [2]. Legatura coeva in pergamena restaurata e rimontata. Interessante manoscritto giuridico fiorentino. € 1600 314 LIBRI, MANOSCRITTI E AUTOGRAFI ~ FIRENZE 11-13 NOVEMBRE 2011 TUTTI I LOTTI SONO RIPRODOTTI IN PIÙ IMMAGINI NEL SITO WWW.GONNELLI.IT GONNELLI CASA D’ASTE GONNELLI CASA D’ASTE In bella legatura coeva alle armi 889. Conferma del titolo di Marchese alla famiglia Bertoldo. Firenze: 1613. Manoscritto pergamenaceo in-4° (mm 280x190). Carte [12] con testo inquadrato da duplice cornice in oro, firma autografa di CosimoII , di Niccolò dell’Antella e di Lorenzo Usimbardi a c. [11]. Bellissima legatura coeva in marocchino rosso alle armi della famiglia Bertoldo, dipinte al centro dei piatti entro elaborata bordura floreale in oro, legacci in seta perfettamente conservati, minimi difetti al dorso. € 2000 890. Testo di solmisazione e mutazione. Prima metà del XVII secolo. Manoscritto a inchiostro nero. Carte [49], scritte recto e verso. Note quadrate scritte su tetragrammi. Alla carta 2r timbro di famiglia nobiliare estinta. Carta proveniente da una cartiera piacentina che terminò la produzione nel 1667. Cartonatura coeva. Dimensioni: mm 415x300. Il manoscritto contiene: carta 1r: «Mano / di Don Guido / Aretino» e di seguito lo schema per praticare la solmisazione.