1968, Tendenza and Education in Aldo Rossi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Friedrichstrasse in Berlin and Central Street in Harbin As Examples1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE HISTORICAL URBAN FABRIC provided by Siberian Federal University Digital Repository UDC 711 Wang Haoyu, Li Zhenyu College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University, China, Shanghai, Yangpu District, Siping Road 1239, 200092 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] COMPARISON STUDY OF TYPICAL HISTORICAL STREET SPACE BETWEEN CHINA AND GERMANY: FRIEDRICHSTRASSE IN BERLIN AND CENTRAL STREET IN HARBIN AS EXAMPLES1 Abstract: The article analyses the similarities and the differences of typical historical street space and urban fabric in China and Germany, taking Friedrichstrasse in Berlin and Central Street in Harbin as examples. The analysis mainly starts from four aspects: geographical environment, developing history, urban space fabric and building style. The two cities have similar geographical latitudes but different climate. Both of the two cities have a long history of development. As historical streets, both of the two streets are the main shopping street in the two cities respectively. The Berlin one is a famous luxury-shopping street while the Harbin one is a famous shopping destination for both citizens and tourists. As for the urban fabric, both streets have fishbone-like spatial structure but with different densities; both streets are pedestrian-friendly but with different scales; both have courtyards space structure but in different forms. Friedrichstrasse was divided into two parts during the World War II and it was partly ruined. It was rebuilt in IBA in the 1980s and many architectural masterpieces were designed by such world-known architects like O.M. -

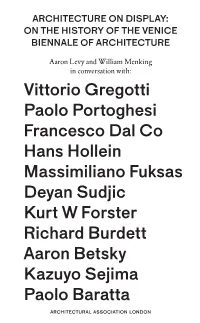

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

“Shall We Compete?”

5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall We Compete?” Pedro Guilherme 35 5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall we compete?” Author Pedro Miguel Hernandez Salvador Guilherme1 CHAIA (Centre for Art History and Artistic Research), Universidade de Évora, Portugal http://uevora.academia.edu/PedroGuilherme (+351) 962556435 [email protected] Abstract Following previous research on competitions from Portuguese architects abroad we propose to show a risomatic string of politic, economic and sociologic events that show why competitions are so much appealing. We will follow Álvaro Siza Vieira and Eduardo Souto de Moura as the former opens the first doors to competitions and the latter follows the master with renewed strength and research vigour. The European convergence provides the opportunity to develop and confirm other architects whose competences and aesthetics are internationally known and recognized. Competitions become an opportunity to other work, different scales and strategies. By 2000, the downfall of the golden initial European years makes competitions not only an opportunity but the only opportunity for young architects. From the early tentative, explorative years of Siza’s firs competitions to the current massive participation of Portuguese architects in foreign competitions there is a long, cumulative effort of competence and visibility that gives international competitions a symbolic, unquestioned value. Keywords International Architectural Competitions, Portugal, Souto de Moura, Siza Vieira, research, decision making Introduction Architects have for long been competing among themselves in competitions. They have done so because they believed competitions are worth it, despite all its negative aspects. There are immense resources allocated in competitions: human labour, time, competences, stamina, expertizes, costs, energy and materials. -

Mauro Marzo Lotus. the First Thirty Years of an Architectural Magazine

DOI: 10.1283/fam/issn2039-0491/n43-2018/142 Mauro Marzo Lotus. The first thirty years of an architectural magazine Abstract Imagined more as an annual dedicated to the best works of architectu- re, urban and industrial design, during the first seven issues, the maga- zine «Lotus» shifts the axis of its purpose from that of information and professional updating to one of a critical examination of the key issues intrinsic to the architectural project. This article identifies some themes, which pervaded the first thirty years of «Lotus» life, from 1964 to 1994, re- emerging, with variations, in many successive issues. If the monographic approach set a characteristic of the editorial line that endures over time, helping to strengthen the magazine’s identity, the change in the themes dealt with over the course of the decades is considered as a litmus test of the continuous evolution of the theoretical-design issues at the core of the architectural debate. Keywords Lotus International — Architectural annual — Little Magazine — Pier- luigi Nicolin — Bruno Alfieri The year 1963 was a memorable one for the British racing driver Jim Clark. At the helm of his Lotus 25 custom-made for him by Colin Chapman, he had won seven of the ten races scheduled for that year. The fastest lap at the Italian Grand Prix held at Monza on 8 September 1963 had allowed him and his team to win the drivers’ title and the Constructors’ Cup,1 with three races to go before the end of the championship. That same day, Chap- man did “the lap of honour astride the hood of his Lotus 25”.2 This car, and its success story, inspired the name chosen for what was initially imagined more as an annual dedicated to the best works of archi- tecture, urban and industrial design, rather than a traditional magazine. -

The Reality of the Imaginary—Architec- and Today, by Integrating the Latest Digital Ima- Ture and the Digital Image

The Reality of the techniques. Although they developed very distinct methods of analysis, they all proceeded from the Imaginary assumption that images are more than just repre- sentations. There is the typological approach of Aldo Rossi; there is the design method of O. M. Architecture and the Digital Image Ungers, which draws on metaphors and visual ana- logies; there is James Stirling’s postmodern collage technique—to name just a few. Others we might Jörg H. Gleiter mention include mvrdv’s diagrammatic and perfor- mative design processes and the de- and recon- struction technique employed by Peter Eisenman and Bernhard Tschumi. As a matter of fact, right from the discovery of perspective in the 15th century and the invention of Cartesian space, the imaging techniques used by I am honored to welcome you all to the 10th Inter- architects have always been more than just techni- national Bauhaus Colloquium. More than 30 years ques of representation. Friedrich Nietzsche once have passed since the 1st Bauhaus Colloquium was said that all our writing tools also work on our held in 1976. The first conference was held in thoughts. How true this is also for the field of archi- honour of the historical Bauhaus in Dessau and its tecture! Drawing on different imaging techniques— 50th anniversary. Since then, the focus of the collo- whether pencil, watercolor or the click of a quium has shifted from history to theory, and mouse—design processes transcribe a certain cultu- towards contemporary architecture and its critical ral logic onto the body of architecture, be it Carte- reassessment. -

9054 MAM MNM Gallery Notes

Museums for a New Millennium Concepts Projects Buildings October 3, 2003 – January 18, 2004 MUSEUMS FOR A NEW MILLENNIUM DOCUMENTS THE REMARKABLE SURGE IN MUSEUM BUILDING AND DEVELOPMENT AT THE TURN OF THE NEW MILLENNIUM. THROUGH MODELS, DRAWINGS, AND PHOTOGRAPHS, IT PRESENTS TWENTY-FIVE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT MUSEUM BUILDING PROJECTS FROM THE PAST TEN YEARS. THE FEATURED PROJECTS — ALL KEY WORKS BY RENOWNED ARCHITECTS — OFFER A PANORAMA OF INTERNATIONAL MUSEUM ARCHITECTURE AT THE OPENING OF THE 21ST CENTURY. Thanks to broad-based public support, MAM is currently in the initial planning phase of its own expansion with Museum Park, the City of Miami’s official urban redesign vision for Bicentennial Park. MAM’s expansion will provide Miami with a 21st-century art museum that will serve as a gathering place for cultural exchange, as well as an educational resource for the community, and a symbol of Miami’s role as a 21st-century city. In the last decade, Miami has quickly become known as the Gateway of the Americas. Despite this unique cultural and economic status, Miami remains the only major city in the United States without a world-class art museum. The Museum Park project realizes a key goal set by the community when MAM was established in 1996. Santiago Calatrava, Milwaukee Art Museum, 1994-2002, Milwaukee, At that time, MAM emerged with a mandate to create Wisconsin. View from the southwest. Photo: Jim Brozek a freestanding landmark building and sculpture park in a premiere, waterfront location. the former kings of France was opened to the public, the Louvre was a direct outcome of the French Revolution. -

Italian Experimentalism and the Contemporary City

Discorsi per Immagini: Of Political and Architectural Experimentation Amit Wolf Queste proposte di lavoro comprendono anche una possibilità di impiego culturale degli architetti al di fuori della professione integrata nel capitale. Attraverso la partecipazione al movimento di classe questi trovano il loro campo di ricerca: l’architettura dal punto di vista operaio, la progettazione delle nuove Karl-Marx-Hof in cui la struttura dell’abitazione collettiva è lo strumento di battaglia. Claudio Greppi and Alberto Pedrolli, “Produzione e programmazione territoriale”1 Of primary interest to us, however, is the question of why, until now, Marxist oriented culture has…denied or concealed the simple truth that, just as there can be no such thing as a political economics of class, but only a class critique of political economics, likewise there can never be an aesthetics, art or architecture of class, but only a class critique of aesthetic, art, architecture and the city. Manfredo Tafuri, “Toward a Critique of Architectural Ideology”2 No account of recent trends in American architecture should fail to mention Manfredo Tafuri’s “Toward a Critique of Architectural Ideology.” This text played a vital role in the distancing of ideas from things in the intellectual conceptualization of the profession; indeed, it set the ground for what is now referred to as “criticality.” The above quotation closes the Roman critic’s essay for the New Left’s first issue of Contropiano. Its final adage follows Tafuri’s dismissal of the possibility of an architectural experimentation that might nudge and expand the field’s stale professionalism in the years around 1968. -

Aldo Rossi a Scientific Autobiography OPPOSITIONS BOOKS Postscript by Vincent Scully Translation by Lawrence Venuti

OPPOSITIONS BOOKS Poatscript by Vincent ScuDy Tranatotion by Lawrence Venutl Aldo Rossi A Scientific Autobiography OPPOSITIONS BOOKS Postscript by Vincent Scully Translation by Lawrence Venuti Aldo Rossi A Scientific Autobiography Published for The Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, Chicago, Illinois. and The Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, New York, New York, by The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England 1981 Copyright @ 1981 by Other Titles in the OPPOSITIONS OPPOSITIONS BOOKS Contents A Scientific Autobiography, 1 The Institute for Architecture and BOOKS series; Drawings,Summerl980, 85 Urban Studies and Editors Postscript: Ideology in Form by Vineent Scully, 111 The Massachusetts Institute of Essays in Architectural Criticism: Peter Eisenman FigureOedits, 118 Technotogy Modern Architecture and Kenneth Frampton Biographical Note, 119 Historical Change All rights reserved. No part of this Alan Colquhoun Managing Editor book may be reproduced in any form Preface by Kenneth Frampton Lindsay Stamm Shapiro or by any means, eleetronic or mechanical, including photocopying, The Architecture ofthe City Assistant Managing Editor recording, or by any information Aldo Rossi Christopher Sweet storage and retrieval system, Introduction by Peter Eisenman without permission in writing from Translation by Diane Ghirardo and Copyeditor the publisher. Joan Ockman Joan Ockman Library ofCongress Catalogning in Designer Pnblieatian Data Massimo Vignelli Rossi, Aldo, 1931- A scientific autobiography. Coordinator "Published for the Graham Abigail Moseley Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine arta, Chieago, Illinois, and ' Production the Institute for Architecture and Larz F. Anderson II Urban Studies, New York, New York." Trustees of the Institute 1. Rossi, Aldo, 1931-. for Architecture and L'rban Studies 2. -

Azu Etd Mr 2015 0128 Sip1 M.Pdf

The Nostalgic Subject and the Reactionary Figure: Italian Architecture in 1972 Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Hayt, Andrew Carlton Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 08:52:49 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/579263 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS This thesis considers the works of two divergent architectural movements in Italy in 1972, the Neo-Rationalist Tendenza and the revolutionary Architettura Radicale, and examines their treatment of the human figure as a means of understanding the strikingly different built environments that were created during the period. The rapidly shifting political, cultural, and socio-psychological milieu in Italy during the years following World War II transformed the meaning of the family unit and the significance of the individual and deeply affected the manner in which architects sought to address the needs of those who inhabited their structures. In Florence the group Superstudio envisioned radical environments that eschewed dominant architectural methodologies in favor of a reductive form of architecture that sought to push capitalistic trends toward their logical and inevitable conclusion. In Milan the architects Aldo Rossi and Carlo Aymonino were constructing the Monte Amiata housing project in the Gallaratese quarter, a series of structures rooted in the architectonic principles of the past, within which the role of the human figure is a more nebulous concept. -

Maeu Behrensrepub 2010.Pdf

007 Carsten Krohn 07 Turit Fröbe 128 Sylvia Necker Einleitung: Stadtkonzepte im 20. Jahrhundert Marcel Breuer: Potsdamer Platz 1929 Hans und Wassili Luckhardt: 020 Regina Stephan 077 Michele Stavagna Rund um den Zoo 1948 Joseph Maria Olbrich: Pariser Platz 1907 Erich Mendelsohn: 131 Eva-Maria Barkhofen 023 Eva Maria Froschauer Hochhaus Friedrichstraße 1929 Sergius Ruegenberg: Hans Bernoulli: Pariser Platz 1907 080 Bernd Nicolai Flughafen am Bahnhof Zoo 1948 026 Wolfgang Sonne Hannes Meyer: Arbeiterbank des ADGB 1929 13 Eduard Kögel Bruno Schmitz: Groß-Berlin 1910 083 Manfred Speidel Richard Paulick: Stalinallee 1951 029 Harald Bodenschatz Bruno Taut: Reichstagserweiterung 1930 137 Florian Seidel Hermann Jansen: Tempelhofer Feld 1910 086 Jan R. Krause Ernst May: Siedlung Fennpfuhl 1957 032 Nikolaus Bernau Egon Eiermann und Fritz Jaenecke: 10 Bernd Bess Ludwig Hoffmann: Justizgebäude Moabit 1930 West-Berliner Senat: Stadtautobahn 1957 Straßenachse zur Museumsinsel 1913 089 Christian Wolsdorff 13 Carola Hein 035 Markus Jager Walter Gropius: Jørn Utzon: Hauptstadt Berlin 1958 Martin Mächler: Nord-Süd-Durchbruch 1920 Wannsee-Uferbebauung 1931 16 Kenneth Frampton 038 Holger Kleine 092 Karin Lelonek Arthur Korn und Stephen Rosenberg: Max Berg: Hochhaus Friedrichstraße 1921 Dominikus Böhm: Hauptstadt Berlin 1958 01 Beatriz Colomina Denkmal der nationalen Arbeit 1933 19 Karsten Schubert Ludwig Mies van der Rohe: 095 Georg Ebbing Walter Schwagenscheidt und Tassilo Sittmann: Hochhaus Friedrichstraße 1921 Otto Kohtz: Hochschulstadt 1937 Hauptstadt -

Carlo Aymonino, One of the Most Important Architects of the Second

In memory of Carlo Aymonino | Manuel de Solà-Morales www.dur.upc.edu 02-2011 Carlo Aymonino, one of the most important architects of the second and in Compte’s philosophical neopositivism—but unless we harken In memory of Carlo Aymonino half of the twentieth century, died in Rome, the city of his birth, on back to Durand or Semper and all that was swept away by the winds of July 3, 2010 at the age of 83. In his writings, seminars, and designs he functionalism, there has been no parallel to Aymonino in contemporary tackled the fundamental problems raised by the shift from the Modern European architectural thought. Movement to the engagement with complexity and the beauty of the His proposal that we recognize the study of the city as a discipline basic real-life, historical, and contemporary city. to all architecture has been simplistically labeled the “typological” At a moment marked by disciplinary fundamentalism and ill approach, and while that may not be a mislabeling, it is notably temperedness, Aymonino advanced, through early writings such as reductive. Drawing similar conclusions as the folks who based the Origini e sviluppo della città moderna (1965), Il significato della città idea of architecture on the progressive rationalization of the hut (1975), and Le città capitali (1975), a vision of city architecture that and identified the origin of composite geometry within the logic of brimmed with tenderness and curiosity. construction, Aymonino is among those who proclaim the city—which is to say agglomeration, hierarchy, and, more generally, the relationship He always approached the city more as an apprentice than a prophet, | Manuel de Solà-Morales and was constantly interweaving the abstract values of urban life with between multifarious forms—as the principle that underlies all an appreciation for the uniquely textured event. -

(1963-74). Three Basque Exercises on Linear Residential Blocks

ACE Architecture, City and Environment E-ISSN 1886-4805 Unités & Hybrids (1963-74). Three Basque exercises on linear residential blocks Lauren Etxepare Igiñiz 1 | Eneko Jokin Uranga Santamaria 2 | Iñigo Lizundia Uranga 3 | Maialen Sagarna Aranburu 4 Received: 2020-04-11 | In its last version: 2020-07-13 Abstract The final result of an architectural experiment, especially in terms of public collective housing, not only responds to the will and creativity of the architects, and to the adoption of canonic models, but it also depends on the specific circumstances of the place where the housing was built. This work examines three residential blocks, built along the Basque coast, which reflect the influence of the main discourses related to linear residential blocks that prevailed in Western Europe in the 60s of the twentieth century. The three cases show the way in which architects, agents and local administrations tried to apply the architectural type in a certain place, and under specific economic and sociopolitical conditions. The article provides an innovative vision, as the authors decided to adopt a geographical framework that transcends the political framework of the time, considering the entire Basque area, where the different architectural discourses were deposited. The original projects of the three case studies have been consulted, as well as general and specific literature relating to each case. Further, a series of interviews were held with the architects responsible for two of the cases. From studying all the publicity around linear blocks carried out between the early 60s and the oil crisis (1974), the authors have obtained the sequence of influences under which these projects were developed.