Johnson's Grid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3. Face and Screen: Toward a Genealogy of the Media Façade

3. Face and Screen: Toward a Genealogy of the Media Façade Craig Buckley Abstract Craig Buckley questions the tendency to see the multi-media façade as paradigmatic of recent developments in illumination and display technologies by reconsidering a longer history of the conflicting urban roles in which façades, as media have been cast. Over the course of the nineteenth century, façades underwent an optical redefinition parallel to that which defined the transformation of the screen. Buildings that sought to do away with a classical conception of the façade also emerged as key sites of experimentation with illuminated screening technologies. Long before the advent of the technical systems animating contemporary media envelopes, the façades of storefronts, cinemas, newspaper offices, union headquarters, and information centres were conceived as media surfaces whose ability to operate on and intervene in their surroundings became more important than the duty to express the building’s interior. Keywords: Urban Screens, Architecture, Space, Physiognomy, Glass, Projection, Billboard Introduction One no longer need travel very far to encounter façades that pulse and move like electronic screens. Media façades have spread far beyond the dense com- mercial nodes with which they were once synonymous—New York’s Times Square, London’s Piccadilly Circus, Berlin’s Alexanderplatz, or Tokyo’s Shibuya. Some of the most ambitious media façades are today realized in places such as Birmingham, Graz, Tallinn, and Jeddah; Abu Dhabi, Tripoli, Montreal, and San Jose; Lima, Melbourne, Seoul, and Ningbo. Within the darkness of Buckley, C., R. Campe, F. Casetti (eds.), Screen Genealogies. From Optical Device to Environmental Medium. -

Oral History Interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12

Oral history interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12 Funding for this interview was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Ann Wilson on 2009 April 19-2010 July 12. The interview took place at Wilson's home in Valatie, New York, and was conducted by Jonathan Katz for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview ANN WILSON: [In progress] "—happened as if it didn't come out of himself and his fixation but merged. It came to itself and is for this moment without him or her, not brought about by him or her but is itself and in this sudden seeing of itself, we make the final choice. What if it has come to be without external to us and what we read it to be then and heighten it toward that reading? If we were to leave it alone at this point of itself, our eyes aging would no longer be able to see it. External and forget the internal ordering that brought it about and without the final decision of what that ordering was about and our emphasis of it, other eyes would miss the chosen point and feel the lack of emphasis. -

Remembering Robert Venturi, a Modern Mannerist

The Plan Journal 4 (1): 253-259, 2019 doi: 10.15274/tpj.2019.04.01.1 Remembering Robert Venturi, a Modern Mannerist In Memoriam / THEORY Maurizio Sabini After the generation of the “founders” of the Modern Movement, very few architects had the same impact that Robert Venturi had on architecture and the way we understand it in our post-modern era. Aptly so and with a virtually universal consensus, Vincent Scully called Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966) “probably the most important writing on the making of architecture since Le Corbusier’s Vers une architecture, of 1923.” 1 And I would submit that no other book has had an equally consequential impact ever since, even though Learning from Las Vegas (published by Venturi with Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour in 1972) has come quite close. As Aaron Betsky has observed: Like the Modernism that Venturi sought to nuance and enrich, many of the elements for which he argued were present in even the most reduced forms of high Modernism. Venturi was trying to save Modernism from its own pronouncements more than from its practices. To a large extent, he won, to the point now that we cannot think of architecture since 1966 without reference to Robert Venturi.2 253 The Plan Journal 4 (1): 253-259, 2019 - doi: 10.15274/tpj.2019.04.01.1 www.theplanjournal.com Figure 1. Robert Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (London: The Architectural Press, with the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1977; or. ed., New York: The Museum of Art, 1966). -

Allen Memorial Art Museum Teacher Resource Packet - AMAM 1977 Addition

Allen Memorial Art Museum Teacher Resource Packet - AMAM 1977 Addition Robert Venturi (American, 1925 – 2018) Allen Memorial Art Museum Addition¸ 1977 Sandstone façade, glass, brick. Robert Venturi was an American architect born in 1925. Best known for being an innovator of postmodern architecture, he and his wife Denise Scott Brown worked on a number of notable museum projects including the 1977 Oberlin addition, the Seattle Museum of Art, and the Sainsbury addition to the National Gallery in London. His architecture is characterized by a sensitive and thoughtful attempt to reconcile the work to its surroundings and function. Biography Robert Venturi was born in 1925 in Philadelphia, PA, and was considered to be one of the foremost postmodern architects of his time. He attended Princeton University in the 1940s, graduating in 1950 summa cum laude. His early experiences were under Eero Saarinen, who designed the famous Gateway Arch in St. Louis, and Louis Kahn, famous for his museum design at the Kimbell Art Museum in Texas and at Yale University. The AMAM addition represents one of Venturi’s first forays into museum design, and was intended to serve as a functional addition to increase gallery and classroom space. Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College For Educational Use Only 1 Venturi was also very well known for his theoretical work in architecture, including Complexity and Contradictions in Architecture (1966), and Learning from Las Vegas (1972). The second book presented the idea of the “decorated shed” and the “duck” as opposing forms of architecture. The Vanna Venturi house was designed for Venturi’s mother in Philadelphia, and is considered one of his masterworks. -

EAAE News Sheet 59

Architecture, Design and Conservation Danish Portal for Artistic and Scientific Research Aarhus School of Architecture // Design School Kolding // Royal Danish Academy Editorial Toft, Anne Elisabeth Published in: EAAE news sheet Publication date: 2001 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for pulished version (APA): Toft, A. E. (2001). Editorial. EAAE news sheet, (59), 5-6. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 European Association for Architectural Education Association Européenne pour l’Enseignement de l’Architecture NEWS SHEET Secretariat AEEA-EAAE April/Avril 2001 Kasteel van Arenberg B-3001 Leuven Bulletin 1/2001 tel ++32/(0)16.321694 fax ++32/(0)16.321962 59 [email protected] http://www.eaae.be Announcements/Annonces Re-integrating Theory and Design in Architectural Education / Réintégration de la Théorie et de la Conception dans l’Enseignement Architectural 19th EAAE CONFERENCE, 23-26 May 2001 A Comment From Ankara and Gazi University on the Threshold of the 19th EAAE Conference Dr. -

Seven to Receive Honorary Degrees UM Sweeps CASE Awards

VERITAFor the Faculty and Staff of the University of Mi: March-April 1997 VolumSe 39 Number 6 Seven to receive honorary degrees oted architects Denise Scott sy-nthesis of nucleic acids. He is the Bethune-Cookman College and Florida affiliated with a number of the great Brown and Robert Venturi. a recipient of numerous other awards, Memorial College, chairman emeritus medical institutions in the United Nhusband-wife team, will be including the Max Berg Award for Pro of the United Protestant Appeal, and States, including Cornell Medical Col honored at this year's Commencement longing Human Life and the Scientific vice president of the Black Archives lege, the Mayo Clinic, and the Univer on May- 9, along with a host of famous Achievement Award of the American Research Foundation. Among his many- sity of Pittsburgh. His books and achievers including Sarah Caldwell; Medical Association. honors are the Greater Miami Urban teachings have influenced the way mil William H. Gray III; a\rthur Romberg; Garth C. Reeves, reporter, editor, League's Distinguished Service Award, lions of children were raised. Garth C. Reeves, Sr.; and Benjamin publisher, banker, entrepreneur, and the American Jew-ish Committee's Robert Venturi. a Philadelphia McLane Spock. In addition to receiving community activist, attended Dade Human Relations Award, the Boy- native, graduated from Princeton Uni an honorary- doctorate. Reeves will County Public Schools and received Scouts Silver Beaver award and the Sil versity. His firm. Venturi, Scott Brown deliver the Commencement address. his bachelor's degree from Florida ver Medallion of the National Confer and Associates, Inc., has made its mark Denise Scott Brow-n, a principal A&M College. -

Friedrichstrasse in Berlin and Central Street in Harbin As Examples1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE HISTORICAL URBAN FABRIC provided by Siberian Federal University Digital Repository UDC 711 Wang Haoyu, Li Zhenyu College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University, China, Shanghai, Yangpu District, Siping Road 1239, 200092 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] COMPARISON STUDY OF TYPICAL HISTORICAL STREET SPACE BETWEEN CHINA AND GERMANY: FRIEDRICHSTRASSE IN BERLIN AND CENTRAL STREET IN HARBIN AS EXAMPLES1 Abstract: The article analyses the similarities and the differences of typical historical street space and urban fabric in China and Germany, taking Friedrichstrasse in Berlin and Central Street in Harbin as examples. The analysis mainly starts from four aspects: geographical environment, developing history, urban space fabric and building style. The two cities have similar geographical latitudes but different climate. Both of the two cities have a long history of development. As historical streets, both of the two streets are the main shopping street in the two cities respectively. The Berlin one is a famous luxury-shopping street while the Harbin one is a famous shopping destination for both citizens and tourists. As for the urban fabric, both streets have fishbone-like spatial structure but with different densities; both streets are pedestrian-friendly but with different scales; both have courtyards space structure but in different forms. Friedrichstrasse was divided into two parts during the World War II and it was partly ruined. It was rebuilt in IBA in the 1980s and many architectural masterpieces were designed by such world-known architects like O.M. -

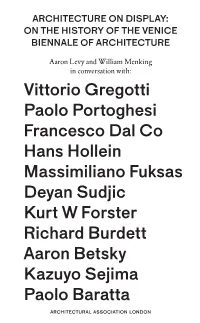

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

“Shall We Compete?”

5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall We Compete?” Pedro Guilherme 35 5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall we compete?” Author Pedro Miguel Hernandez Salvador Guilherme1 CHAIA (Centre for Art History and Artistic Research), Universidade de Évora, Portugal http://uevora.academia.edu/PedroGuilherme (+351) 962556435 [email protected] Abstract Following previous research on competitions from Portuguese architects abroad we propose to show a risomatic string of politic, economic and sociologic events that show why competitions are so much appealing. We will follow Álvaro Siza Vieira and Eduardo Souto de Moura as the former opens the first doors to competitions and the latter follows the master with renewed strength and research vigour. The European convergence provides the opportunity to develop and confirm other architects whose competences and aesthetics are internationally known and recognized. Competitions become an opportunity to other work, different scales and strategies. By 2000, the downfall of the golden initial European years makes competitions not only an opportunity but the only opportunity for young architects. From the early tentative, explorative years of Siza’s firs competitions to the current massive participation of Portuguese architects in foreign competitions there is a long, cumulative effort of competence and visibility that gives international competitions a symbolic, unquestioned value. Keywords International Architectural Competitions, Portugal, Souto de Moura, Siza Vieira, research, decision making Introduction Architects have for long been competing among themselves in competitions. They have done so because they believed competitions are worth it, despite all its negative aspects. There are immense resources allocated in competitions: human labour, time, competences, stamina, expertizes, costs, energy and materials. -

Latin Books Published in Paris, 1501-1540

Latin Books Published in Paris, 1501-1540 Sophie Mullins This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 6 September 2013 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Sophie Anne Mullins hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 76,400 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2007 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2007; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between [2007] and 2013. (If you received assistance in writing from anyone other than your supervisor/s): I, …..., received assistance in the writing of this thesis in respect of [language, grammar, spelling or syntax], which was provided by …… Date 2/5/14 signature of candidate ……… 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. Date 2/5/14 signature of supervisor ……… 3. Permission for electronic publication: (to be signed by both candidate and supervisor) In submitting this thesis to the University of St Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. -

Secretaries of Defense

Secretaries of Defense 1947 - 2021 Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense Contents Historical Origins of the Secretary of Defense . iii Secretaries of Defense . 1 Secretaries of Defense Demographics . 28 History of the Positional Colors for the Office of the Secretary of Defense . 29 “The Secretary of Defense’s primary role is to ensure the national security . [and] it is one of the more difficult jobs anywhere in the world. He has to be a mini-Secretary of State, a procurement expert, a congressional relations expert. He has to understand the budget process. And he should have some operational knowledge.” Frank C. Carlucci former Secretary of Defense Prepared by Dr. Shannon E. Mohan, Historian Dr. Erin R. Mahan, Chief Historian Secretaries of Defense i Historical Origins of the Secretary of Defense The 1947 National Security Act (P.L. 80-253) created the position of Secretary of Defense with authority to establish general policies and programs for the National Military Establishment. Under the law, the Secretary of Defense served as the principal assistant to the President in all matters relating to national security. James V. Forrestal is sworn in as the first Secretary of Defense, September 1947. (OSD Historical Office) The 1949 National Security Act Amendments (P.L. 81- 216) redefined the Secretary of Defense’s role as the President’s principal assistant in all matters relating to the Department of Defense and gave him full direction, authority, and control over the Department. Under the 1947 law and the 1949 Amendments, the Secretary was appointed from civilian life provided he had not been on active duty as a commissioned officer within ten years of his nomination. -

Architectsnewspaper 11 6.22.2005

THE ARCHITECTSNEWSPAPER 11 6.22.2005 NEW YORK ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN WWW.ARCHPAPER.COM $3.95 GUGGENBUCKS, GUGGENDALES, CO GUGGENSOLES 07 MIAMI NICE LU ARTISTIC Z O GO HOME, LICENSING o DAMN YANKEES 12 Once again, the ever-expanding Guggenheim is moving to new frontiers. TOP OF THE A jury that included politicians, Frank CLASS Gehry and Thomas Krens has awarded 4 the design commission for the newest 17 museum in the Guggenheim orbitto VENTURI AND Enrique Norten for a 50-story structure on a cliff outside Guadalajara, Mexico's sec• SCOTT BROWN ond-largest city. The museum will cost BRITISH TEAM WINS VAN ALEN COMPETITION PROBE THE PAST the city about $250 million to build. 03 EAVESDROP But there is now a far less expensive 18 DIARY range of associations with the Guggenheim 20 PROTEST Coney Island Looks Up brand. The Guggenheim is actively 23 CLASSIFIEDS exploring the market for products that it On May 26 Sherida E. Paulsen, chair of the Fair to Coney Island in 1940, closed in 1968, can license, in the hope of Guggenheim- Van Alen Institute's board of trustees, and but the 250-foot-tall structure was land- ing tableware, jewelry, even paint. An Joshua J. Sirefman, CEO of the Coney marked in 1989. eyewear deal is imminent. Island Development Corporation (CIDC), Brooklyn-based Ramon Knoester and It's not the museum's first effort to announced the winners of the Parachute Eckart Graeve took the second place prize license products but it is its first planned Pavilion Design Competition at an event on of S5,000, and a team of five architects strategy to systematize licensing.