Agnes Martin, Textiles, and the Linear Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weaverswaver00stocrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Fiber Arts Oral History Series Kay Sekimachi THE WEAVER'S WEAVER: EXPLORATIONS IN MULTIPLE LAYERS AND THREE-DIMENSIONAL FIBER ART With an Introduction by Signe Mayfield Interviews Conducted by Harriet Nathan in 1993 Copyright 1996 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Kay Sekimachi dated April 16, 1995. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Oral History Interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12

Oral history interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12 Funding for this interview was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Ann Wilson on 2009 April 19-2010 July 12. The interview took place at Wilson's home in Valatie, New York, and was conducted by Jonathan Katz for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview ANN WILSON: [In progress] "—happened as if it didn't come out of himself and his fixation but merged. It came to itself and is for this moment without him or her, not brought about by him or her but is itself and in this sudden seeing of itself, we make the final choice. What if it has come to be without external to us and what we read it to be then and heighten it toward that reading? If we were to leave it alone at this point of itself, our eyes aging would no longer be able to see it. External and forget the internal ordering that brought it about and without the final decision of what that ordering was about and our emphasis of it, other eyes would miss the chosen point and feel the lack of emphasis. -

THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM of ART ANNUAL REPORT 2002 1 0-Cover.P65 the CLEVELAND MUSEUM of ART

ANNUAL REPORT 2002 THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART REPORT 2002 ANNUAL 0-Cover.p65 1 6/10/2003, 4:08 PM THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART ANNUAL REPORT 2002 1-Welcome-A.p65 1 6/10/2003, 4:16 PM Feathered Panel. Peru, The Cleveland Narrative: Gregory Photography credits: Brichford: pp. 7 (left, Far South Coast, Pampa Museum of Art M. Donley Works of art in the both), 9 (top), 11 Ocoña; AD 600–900; 11150 East Boulevard Editing: Barbara J. collection were photo- (bottom), 34 (left), 39 Cleveland, Ohio Bradley and graphed by museum (top), 61, 63, 64, 68, Papagayo macaw feathers 44106–1797 photographers 79, 88 (left), 92; knotted onto string and Kathleen Mills Copyright © 2003 Howard Agriesti and Rodney L. Brown: p. stitched to cotton plain- Design: Thomas H. Gary Kirchenbauer 82 (left) © 2002; Philip The Cleveland Barnard III weave cloth, camelid fiber Museum of Art and are copyright Brutz: pp. 9 (left), 88 Production: Charles by the Cleveland (top), 89 (all), 96; plain-weave upper tape; All rights reserved. 81.3 x 223.5 cm; Andrew R. Szabla Museum of Art. The Gregory M. Donley: No portion of this works of art them- front cover, pp. 4, 6 and Martha Holden Jennings publication may be Printing: Great Lakes Lithograph selves may also be (both), 7 (bottom), 8 Fund 2002.93 reproduced in any protected by copy- (bottom), 13 (both), form whatsoever The type is Adobe Front cover and frontispiece: right in the United 31, 32, 34 (bottom), 36 without the prior Palatino and States of America or (bottom), 41, 45 (top), As the sun went down, the written permission Bitstream Futura abroad and may not 60, 62, 71, 77, 83 (left), lights came up: on of the Cleveland adapted for this be reproduced in any 85 (right, center), 91; September 11, the facade Museum of Art. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 29:2 — Fall 2017 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Fall 2017 Textile Society of America Newsletter 29:2 — Fall 2017 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Industrial and Product Design Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, and the Metal and Jewelry Arts Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 29:2 — Fall 2017" (2017). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 80. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/80 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 29. NUMBER 2. FALL 2017 Photo Credit: Tourism Vancouver See story on page 6 Newsletter Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS Editor-in-Chief: Wendy Weiss (TSA Board Member/Director of Communications) Designer: Meredith Affleck Vita Plume Member News Editor: Caroline Charuk (TSA General Manager) President [email protected] Editorial Assistance: Natasha Thoreson and Sarah Molina Lisa Kriner Vice President/President Elect Our Mission [email protected] Roxane Shaughnessy The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for Past President the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, [email protected] political, social, and technical perspectives. Established in 1987, TSA is governed by a Board of Directors from museums and universities in North America. -

Keynote Addressâ•Flsummary Notes

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2004 Keynote Address—Summary Notes Jack Lenor Larsen Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Larsen, Jack Lenor, "Keynote Address—Summary Notes" (2004). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 494. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/494 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Keynote Address—Summary Notes San Francisco Bay as the Fountainhead and Wellspring Jack Lenor Larsen Jack Lenor Larsen led off the 9th Biennial Symposium of the Textile Society of America in Oakland, California, with a plenary session directed to TSA members and conference participants. He congratulated us, even while proposing a larger and more inclusive vision of our field, and exhorting us to a more comprehensive approach to fiber. His plenary remarks were spoken extemporaneously from notes and not recorded. We recognize that their inestimable value deserves to be shared more broadly; Jack has kindly provided us with his rough notes for this keynote address. The breadth of his vision, and his insightful comments regarding fiber and art, are worthy of thoughtful consideration by all who concern themselves with human creativity. On the Textile Society of America Larsen proffered congratulations on the Textile Society of America, now fifteen years old. -

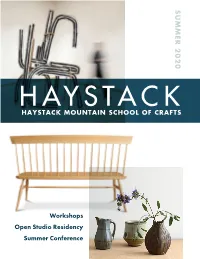

Workshops Open Studio Residency Summer Conference

SUMMER 2020 HAYSTACK MOUNTAIN SCHOOL OF CRAFTS Workshops Open Studio Residency Summer Conference Schedule at a Glance 4 SUMMER 2020 Life at Haystack 6 Open Studio Residency 8 Session One 10 Welcome Session Two This year will mark the 70th anniversary of the 14 Haystack Mountain School of Crafts. The decision to start a school is a radical idea in and Session Three 18 of itself, and is also an act of profound generosity, which hinges on the belief that there exists something Session Four 22 so important it needs to be shared with others. When Haystack was founded in 1950, it was truly an experiment in education and community, with no News & Updates 26 permanent faculty or full-time students, a school that awarded no certificates or degrees. And while the school has grown in ways that could never have been Session Five 28 imagined, the core of our work and the ideas we adhere to have stayed very much the same. Session Six 32 You will notice that our long-running summer conference will take a pause this season, but please know that it will return again in 2021. In lieu of a Summer Workshop 36 public conference, this time will be used to hold Information a symposium for the Haystack board and staff, focusing on equity and racial justice. We believe this is vital Summer Workshop work for us to be involved with and hope it can help 39 make us a more inclusive organization while Application broadening access to the field. As we have looked back to the founding years of the Fellowships 41 school, together we are writing the next chapter in & Scholarships Haystack’s history. -

Working Checklist 00

Taking a Thread for a Walk The Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 21, 2019 - June 01, 2020 WORKING CHECKLIST 00 - Introduction ANNI ALBERS (American, born Germany. 1899–1994) Untitled from Connections 1983 One from a portfolio of nine screenprints composition: 17 3/4 × 13 3/4" (45.1 × 34.9 cm); sheet: 27 3/8 × 19 1/2" (69.5 × 49.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in memory of Joseph Fearer Weber/Danilowitz 74 Wall, framed. Located next to projection in elevator bank ANNI ALBERS (American, born Germany. 1899–1994) Study for Nylon Rug from Connections 1983 One from a portfolio of nine screenprints composition: 20 5/8 × 15 1/8" (52.4 × 38.4 cm); sheet: 27 3/8 × 19 1/2" (69.5 × 49.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in memory of Joseph Fearer Weber/Danilowitz 75 Wall, framed. Located next to projection in elevator bank ANNI ALBERS (American, born Germany. 1899–1994) With Verticals from Connections 1983 One from a portfolio of nine screenprints composition: 19 3/8 × 14 1/4" (49.2 × 36.2 cm); sheet: 27 3/8 × 19 1/2" (69.5 × 49.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in memory of Joseph Fearer Weber/Danilowitz 73 Wall, framed. Located next to projection in elevator bank ANNI ALBERS (American, born Germany. 1899–1994) Orchestra III from Connections 1983 One from a portfolio of nine screenprints composition: 26 5/8 × 18 7/8" (67.6 × 47.9 cm); sheet: 27 3/8 × 19 1/2" (69.5 × 49.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. -

ORNAMENT 30.3.2007 30.3 TOC 2.FIN 3/18/07 12:39 PM Page 2

30.3 COVERs 3/18/07 2:03 PM Page 1 992-994_30.3_ADS 3/18/07 1:16 PM Page 992 01-011_30.3_ADS 3/16/07 5:18 PM Page 1 JACQUES CARCANAGUES, INC. LEEKAN DESIGNS 21 Greene Street New York, NY 10013 BEADS AND ASIAN FOLKART Jewelry, Textiles, Clothing and Baskets Furniture, Religious and Domestic Artifacts from more than twenty countries. WHOLESALE Retail Gallery 11:30 AM-7:00 PM every day & RETAIL (212) 925-8110 (212) 925-8112 fax Wholesale Showroom by appointment only 93 MERCER STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10012 (212) 431-3116 (212) 274-8780 fax 212.226.7226 fax: 212.226.3419 [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] WHOLESALE CATALOG $5 & TAX I.D. Warehouse 1761 Walnut Street El Cerrito, CA 94530 Office 510.965.9956 Pema & Thupten Fax 510.965.9937 By appointment only Cell 510.812.4241 Call 510.812.4241 [email protected] www.tibetanbeads.com 1 ORNAMENT 30.3.2007 30.3 TOC 2.FIN 3/18/07 12:39 PM Page 2 volumecontents 30 no. 3 Ornament features 34 2007 smithsonian craft show by Carl Little 38 candiss cole. Reaching for the Exceptional by Leslie Clark 42 yazzie johnson and gail bird. Aesthetic Companions by Diana Pardue 48 Biba Schutz 48 biba schutz. Haunting Beauties by Robin Updike Candiss Cole 38 52 mariska karasz. Modern Threads by Ashley Callahan 56 tutankhamun’s beadwork by Jolanda Bos-Seldenthuis 60 carol sauvion’s craft in america by Carolyn L.E. Benesh 64 kristina logan. Master Class in Glass Beadmaking by Jill DeDominicis Cover: BUTTERFLY PINS by Yazzie Johnson and Gail Bir d, from top to bottom: Morenci tur quoise and tufa-cast eighteen karat gold, 7.0 centimeters wide, 2005; Morenci turquoise, lapis, azurite and fourteen karat gold, 5.1 centimeters wide, 1987; Morenci turquoise and tufa-cast eighteen karat gold, 5.7 centimeters wide, 2005; Tyrone turquoise, coral and tufa- cast eighteen karat gold, 7.6 centimeters wide, 2006; Laguna agates and silver, 7.6 centimeters wide, 1986. -

Oral History Interview with Anne Wilson, 2012 July 6-7

Oral history interview with Anne Wilson, 2012 July 6-7 Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Transcription of this oral history interview was made possible by a grant from the Smithsonian Women's Committee. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Anne Wilson on July 6 and 7, 2012. The interview took place in the artist's studio in Evanston, Illinois, and was conducted by Mija Riedel for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Anne Wilson and Mija Riedel have reviewed the transcript. Their heavy corrections and emendations appear below in brackets with initials. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview MIJA RIEDEL: This is Mija Riedel with Anne Wilson at the artist's studio in Evanston, Illinois, on July 6, 2012, for the Smithsonian Institution's Archives of American Art. This is disc number one. So, Anne, let's just take care of some of the early biographical information first. You were born in Detroit in 1949? ANNE WILSON: I was. MS. RIEDEL: Okay. And would you tell me your parents' names? MS. -

Architectsnewspaper 11 6.22.2005

THE ARCHITECTSNEWSPAPER 11 6.22.2005 NEW YORK ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN WWW.ARCHPAPER.COM $3.95 GUGGENBUCKS, GUGGENDALES, CO GUGGENSOLES 07 MIAMI NICE LU ARTISTIC Z O GO HOME, LICENSING o DAMN YANKEES 12 Once again, the ever-expanding Guggenheim is moving to new frontiers. TOP OF THE A jury that included politicians, Frank CLASS Gehry and Thomas Krens has awarded 4 the design commission for the newest 17 museum in the Guggenheim orbitto VENTURI AND Enrique Norten for a 50-story structure on a cliff outside Guadalajara, Mexico's sec• SCOTT BROWN ond-largest city. The museum will cost BRITISH TEAM WINS VAN ALEN COMPETITION PROBE THE PAST the city about $250 million to build. 03 EAVESDROP But there is now a far less expensive 18 DIARY range of associations with the Guggenheim 20 PROTEST Coney Island Looks Up brand. The Guggenheim is actively 23 CLASSIFIEDS exploring the market for products that it On May 26 Sherida E. Paulsen, chair of the Fair to Coney Island in 1940, closed in 1968, can license, in the hope of Guggenheim- Van Alen Institute's board of trustees, and but the 250-foot-tall structure was land- ing tableware, jewelry, even paint. An Joshua J. Sirefman, CEO of the Coney marked in 1989. eyewear deal is imminent. Island Development Corporation (CIDC), Brooklyn-based Ramon Knoester and It's not the museum's first effort to announced the winners of the Parachute Eckart Graeve took the second place prize license products but it is its first planned Pavilion Design Competition at an event on of S5,000, and a team of five architects strategy to systematize licensing. -

Louise Bourgeois Turning Inwards

Turning Inwards Turning Louise Bourgeois Hauser & Wirth Somerset 2 October 2016 – 1 January 2017 Education Guide This resource has been produced to accompany the exhibition, ‘Louise Bourgeois. Turning Inwards’, at Hauser & Wirth Somerset. Hauser & Wirth Somerset is a pioneering world-class gallery and multi-purpose arts centre, which provides a destination for experiencing art, architecture and the remarkable Somerset landscape through new and innovative exhibitions of contemporary art. A landscaped garden, designed for the gallery by internationally renowned landscape architect Piet Oudolf and the Radić Pavilion (the Serpentine Gallery 2014 Pavilion), designed by Chilean architect Smiljan Radić, both sit behind the galleries. This publication is designed for teachers and students, to be used alongside their visit to the exhibition. It provides an introduction to the artist Louise Bourgeois, identifies the key themes of her work and makes reference to the historical and theoretical contexts in which her practice can be understood. It offers activities, which can be carried out during a visit to the gallery and topics for discussion and additional research. The exhibition features a body of painting, print, drawing and sculpture, most of which has been curated in relation to the existing farm buildings and new architecture at Hauser & Wirth Somerset, creating a new environment and experience of Louise Bourgeois’s work in Somerset. Oudolf Field, Hauser & Wirth Somerset 2016. Photo: Jason Ingram About Louise Bourgeois Louise Joséphine Bourgeois was born in Paris 1977 and 2002, Bourgeois was the recipient on Christmas Day in 1911. She was one of three of 7 Honorary Doctorates of Fine Arts from children; their parents ran an Aubusson tapestry institutions such as Yale University and the Art restoration business and a tapestry gallery in Paris. -

Selected Bibliography and Exhibition History

6/6/11 n11 Karlstrom_bib.doc: 163 Selected Bibliography and Exhibition History The following selected bibliography and exhibition history have been compiled by Jeff Gunderson, longtime librarian at the San Francisco Art Institute, the intended repository for the Peter Selz library. Gunderson worked closely with the author of this book, along with Selz himself, in setting up the guidelines for inclusion. For a full bibliography of articles, essays, books, and catalogues by Peter Selz, as well as a complete list of exhibitions for which he was curator, see www.ucpress.edu/go/peterselz. The lists presented here demonstrate Selz’s wide range of interests and expertise, as well as his advocacy for fine artists and his belief that art can be a fitting vehicle for social and political commentary. For the two bibliographic sections, “Books and Catalogues” and “Journal Articles and Essays,” the selection of titles was made on the basis of their significance and the contribution that they represent. Although Selz has been involved in and responsible for numerous exhibition-related publications, the extent of his involvement in these catalogues has varied widely. Those listed here (and indicated by an asterisk) are for the projects in which he took the lead authorial role, whatever his position in conceiving or producing the accompanying exhibition. Selz wrote a great number of magazine articles and reviews as well, many of them as West Coast correspondent for Art in America. With few exceptions, the regional exhibition reviews are not included. On the other hand, independent articles that represent the development and application of his thinking about modernist art are cited.