Fiberartoral00lakyrich.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weaverswaver00stocrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Fiber Arts Oral History Series Kay Sekimachi THE WEAVER'S WEAVER: EXPLORATIONS IN MULTIPLE LAYERS AND THREE-DIMENSIONAL FIBER ART With an Introduction by Signe Mayfield Interviews Conducted by Harriet Nathan in 1993 Copyright 1996 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Kay Sekimachi dated April 16, 1995. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 29:2 — Fall 2017 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Fall 2017 Textile Society of America Newsletter 29:2 — Fall 2017 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Industrial and Product Design Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, and the Metal and Jewelry Arts Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 29:2 — Fall 2017" (2017). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 80. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/80 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 29. NUMBER 2. FALL 2017 Photo Credit: Tourism Vancouver See story on page 6 Newsletter Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS Editor-in-Chief: Wendy Weiss (TSA Board Member/Director of Communications) Designer: Meredith Affleck Vita Plume Member News Editor: Caroline Charuk (TSA General Manager) President [email protected] Editorial Assistance: Natasha Thoreson and Sarah Molina Lisa Kriner Vice President/President Elect Our Mission [email protected] Roxane Shaughnessy The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for Past President the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, [email protected] political, social, and technical perspectives. Established in 1987, TSA is governed by a Board of Directors from museums and universities in North America. -

Keynote Addressâ•Flsummary Notes

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2004 Keynote Address—Summary Notes Jack Lenor Larsen Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Larsen, Jack Lenor, "Keynote Address—Summary Notes" (2004). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 494. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/494 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Keynote Address—Summary Notes San Francisco Bay as the Fountainhead and Wellspring Jack Lenor Larsen Jack Lenor Larsen led off the 9th Biennial Symposium of the Textile Society of America in Oakland, California, with a plenary session directed to TSA members and conference participants. He congratulated us, even while proposing a larger and more inclusive vision of our field, and exhorting us to a more comprehensive approach to fiber. His plenary remarks were spoken extemporaneously from notes and not recorded. We recognize that their inestimable value deserves to be shared more broadly; Jack has kindly provided us with his rough notes for this keynote address. The breadth of his vision, and his insightful comments regarding fiber and art, are worthy of thoughtful consideration by all who concern themselves with human creativity. On the Textile Society of America Larsen proffered congratulations on the Textile Society of America, now fifteen years old. -

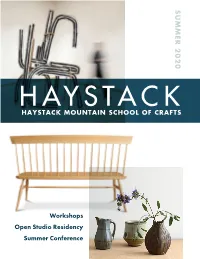

Workshops Open Studio Residency Summer Conference

SUMMER 2020 HAYSTACK MOUNTAIN SCHOOL OF CRAFTS Workshops Open Studio Residency Summer Conference Schedule at a Glance 4 SUMMER 2020 Life at Haystack 6 Open Studio Residency 8 Session One 10 Welcome Session Two This year will mark the 70th anniversary of the 14 Haystack Mountain School of Crafts. The decision to start a school is a radical idea in and Session Three 18 of itself, and is also an act of profound generosity, which hinges on the belief that there exists something Session Four 22 so important it needs to be shared with others. When Haystack was founded in 1950, it was truly an experiment in education and community, with no News & Updates 26 permanent faculty or full-time students, a school that awarded no certificates or degrees. And while the school has grown in ways that could never have been Session Five 28 imagined, the core of our work and the ideas we adhere to have stayed very much the same. Session Six 32 You will notice that our long-running summer conference will take a pause this season, but please know that it will return again in 2021. In lieu of a Summer Workshop 36 public conference, this time will be used to hold Information a symposium for the Haystack board and staff, focusing on equity and racial justice. We believe this is vital Summer Workshop work for us to be involved with and hope it can help 39 make us a more inclusive organization while Application broadening access to the field. As we have looked back to the founding years of the Fellowships 41 school, together we are writing the next chapter in & Scholarships Haystack’s history. -

Design Competition Brief

Design Competition Brief The Museum of the 20th Century Berlin, June 2016 Publishing data Design competition brief compiled by: ARGE WBW-M20 Schindler Friede Architekten, Salomon Schindler a:dks mainz berlin, Marc Steinmetz On behalf of: Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz (SPK) Von-der-Heydt-Straße 16-18 10785 Berlin Date / as of: 24/06/2016 Design Competition Brief The Museum of the 20th Century Part A Competition procedure ..............................................................................5 A.1 Occasion and objective .......................................................................................... 6 A.2 Parties involved in the procedure ........................................................................... 8 A.3 Competition procedure .......................................................................................... 9 A.4 Eligibility ............................................................................................................... 11 A.5 Jury, appraisers, preliminary review ...................................................................... 15 A.6 Competition documents ....................................................................................... 17 A.7 Submission requirements ...................................................................................... 18 A.8 Queries ................................................................................................................. 20 A.9 Submission of competition entries and preliminary review ................................. -

The Factory of Visual

ì I PICTURE THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE LINE OF PRODUCTS AND SERVICES "bey FOR THE JEWELRY CRAFTS Carrying IN THE UNITED STATES A Torch For You AND YOU HAVE A GOOD PICTURE OF It's the "Little Torch", featuring the new controllable, méf » SINCE 1923 needle point flame. The Little Torch is a preci- sion engineered, highly versatile instrument capa- devest inc. * ble of doing seemingly impossible tasks with ease. This accurate performer welds an unlimited range of materials (from less than .001" copper to 16 gauge steel, to plastics and ceramics and glass) with incomparable precision. It solders (hard or soft) with amazing versatility, maneuvering easily in the tightest places. The Little Torch brazes even the tiniest components with unsurpassed accuracy, making it ideal for pre- cision bonding of high temp, alloys. It heats any mate- rial to extraordinary temperatures (up to 6300° F.*) and offers an unlimited array of flame settings and sizes. And the Little Torch is safe to use. It's the big answer to any small job. As specialists in the soldering field, Abbey Materials also carries a full line of the most popular hard and soft solders and fluxes. Available to the consumer at manufacturers' low prices. Like we said, Abbey's carrying a torch for you. Little Torch in HANDY KIT - —STARTER SET—$59.95 7 « '.JBv STARTER SET WITH Swest, Inc. (Formerly Southwest Smelting & Refining REGULATORS—$149.95 " | jfc, Co., Inc.) is a major supplier to the jewelry and jewelry PRECISION REGULATORS: crafts fields of tools, supplies and equipment for casting, OXYGEN — $49.50 ^J¡¡r »Br GAS — $49.50 electroplating, soldering, grinding, polishing, cleaning, Complete melting and engraving. -

California and the Fiber Art Revolution

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2004 California and the Fiber Art Revolution Suzanne Baizerman Oakland Museum of California, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Baizerman, Suzanne, "California and the Fiber Art Revolution" (2004). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 449. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/449 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. California and the Fiber Art Revolution Suzanne Baizerman Imogene Gieling Curator of Crafts and Decorative Arts Oakland Museum of California Oakland, CA 510-238-3005 [email protected] In the 1960s and ‘70s, California artists participated in and influenced an international revolution in fiber art. The California Design (CD) exhibitions, a series held at the Pasadena Art Museum from 1955 to 1971 (and at another venue in 1976) captured the form and spirit of the transition from handwoven, designer textiles to two dimensional fiber art and sculpture.1 Initially, the California Design exhibits brought together manufactured and one-of-a kind hand-crafted objects, akin to the Good Design exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. -

Ar204 Art and Interpretation

AR204 ART AND INTERPRETATION Art and Aesthetics Module: Art Objects and Experience Fall 2019 Seminar Leader: Geoff Lehman Course Times: Wednesday, 9:00- 10:30 and Friday, 10:45-12:15 (9:00-12:15 for museum visits) Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesdays, 14:00-16:00 Course Description Describing a painting, the art historian Leo Steinberg wrote: “The picture conducts itself the way a vital presence behaves. It creates an encounter.” In this course, we will encounter works of art to explore the specific dialogue each creates with a viewer and the range of interpretive possibilities it offers. More specifically, the course will examine various interpretive approaches to art, including formal analysis, iconography, social and historical contextualism, aestheticism, phenomenology, and psychoanalysis. Most importantly, we will engage interpretation in ways that are significant both within art historical discourse and in addressing larger questions of human experience and (self- )knowledge, considering the dialogue with the artwork in its affective (emotional) as well as its intellectual aspects. The course will be guided throughout by sustained discussion of a small number of individual artworks, with a focus on pictorial representation (painting, drawing, photography), although sculpture and installation art will also be considered. We will look at works from a range of different cultural traditions, and among the artists we will focus on are Xia Gui, Giorgione, Bruegel, Mirza Ali, Velázquez, Hokusai, Manet, Picasso, Man Ray, Martin, and Sherman. Readings will focus on texts in art history and theory but also include philosophical and psychoanalytic texts (Pater, Wölfflin, Freud, Merleau-Ponty, Barthes, Clark, and Krauss, among others). -

Bay-Area-Clay-Exhibi

A Legacy of Social Consciousness Bay Area Clay Arts Benicia 991 Tyler Street, Suite 114 Benicia, CA 94510 Gallery Hours: Wednesday-Sunday, 12-5 pm 707.747.0131 artsbenicia.org October 14 - November 19, 2017 Bay Area Clay A Legacy of Social Consciousness Funding for Bay Area Clay - a Legacy of Social Consciousness is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency. A Legacy of Social Consciousness I want to thank every artist in this exhibition for their help and support, and for the powerful art that they create and share with the world. I am most grateful to Richard Notkin for sharing his personal narrative and philosophical insight on the history of Clay and Social Consciousness. –Lisa Reinertson Thank you to the individual artists and to these organizations for the loan of artwork for this exhibition: The Artists’ Legacy Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, NY for the loan of Viola Frey’s work Dolby Chadwick Gallery and the Estate of Stephen De Staebler The Estate of Robert Arneson and Sandra Shannonhouse The exhibition and catalog for Bay Area Clay – A Legacy of Social Consciousness were created and produced by the following: Lisa Reinertson, Curator Arts Benicia Staff: Celeste Smeland, Executive Director Mary Shaw, Exhibitions and Programs Manager Peg Jackson, Administrative Coordinator and Graphics Designer Jean Purnell, Development Associate We are deeply grateful to the following individuals and organizations for their support of this exhibition. National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency, -

Museum of Arts and Design

SPRING/SUMMER BULLETIN 2011 vimuseume of artsws and design Dear Friends, Board of Trustees Holly Hotchner LEWIS KRUGER Nanette L. Laitman Director Chairman What a whirlwind fall! Every event seemed in some way or another a new milestone for JEROME A. CHAZEN us all at 2 Columbus Circle. And it all started with a public program that you might have Chairman Emeritus thought would slip under the radar—Blood into Gold: The Cinematic Alchemy of Alejandro BARbaRA TOBER Chairman Emerita Jodorowsky. Rather than attracting a small band of cinéastes, this celebration of the Chilean- FRED KLEISNER born, Paris-based filmmaker turned into a major event: not only did the screenings sell Treasurer out, but the maestro’s master class packed our seventh-floor event space to fire-code LINDA E. JOHNSON Secretary capacity and elicited a write-up in the Wall Street Journal! And that’s not all, none other HOllY HOtcHNER than Debbie Harry introduced Jodorowsky’s most famous filmThe Holy Mountain to Director filmgoers, among whom were several downtown art stars, including Klaus Biesenbach, the director of MoMA PS1. A huge fan of this mystical renaissance man, Biesenbach was StaNLEY ARKIN DIEGO ARRIA so impressed by our series that beginning on May 22, MoMA PS1 will screen The Holy GEORGE BOURI Mountain continuously until June 30. And, he has graciously given credit to MAD and KAY BUckSbaUM Jake Yuzna, our manager of public programs, for inspiring the film installation. CECILY CARSON SIMONA CHAZEN MICHELE COHEN Jodorowsky wasn’t the only Chilean artist presented at MAD last fall. Several had works ERIC DObkIN featured in Think Again: New Latin American Jewelry. -

Deliberate Entanglements: the Impact of a Visionary Exhibition Emily Zaiden

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 9-2014 Deliberate Entanglements: The mpI act of a Visionary Exhibition Emily Zaiden [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Art Practice Commons Zaiden, Emily, "Deliberate Entanglements: The mpI act of a Visionary Exhibition" (2014). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 887. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/887 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Deliberate Entanglements: The Impact of a Visionary Exhibition Emily Zaiden Figure 1. Deliberate Entanglements exhibition announcement designed by Timothy Andersen, UCLA Art Galleries, 1971. Courtesy Craft in America Center Archives. In the trajectory of fiber art history, the 1971 UCLA Art Galleries exhibition, Deliberate Entanglements, was exceptional in that it had an active and direct influence on the artistic movement. It has been cited in numerous sources, by participating artists, and by others who simply visited and attended as having had a lasting impact on their careers. In this day and age, it is rare for exhibitions at institutions to play such a powerful role and have a lasting impact. The exhibition was curated by UCLA art professor and fiber program head, Bernard Kester. From his post at UCLA, Kester fostered fiber as a medium for contemporary art. -

The Wood Turning Center Is a Non-Profit Arts Institution Dedicated

Chronological List of Exhibitions & Publications The Center for Art in Wood 141 N. 3rd Street | Philadelphia, PA 19106 | 215-923-8000 Exhibitions in italics were accompanied by publications. Title of exhibition catalogue is listed with its details. 2013 Shadow of the Turning: The Art of Binh Pho, The Center for Art in Wood, October 25, 2013 – January 18, 2014. Organized by Binh Pho & Kevin Wallace Shadow of the Turning is a traveling exhibition focuses on art, philosophy and storytelling of artist Binh Pho. Blending the mythic worlds of fairy tale, fantasy, adventure and science fiction, this exhibit creates a bridge between literature, art world approaches to concept and narrative, craft traditions and mixed media approaches. The story is “illustrated” using an exciting new body of work by Binh Pho, which combines woodturning, sculpture, painting and art glass. Exhibited Artist: Binh Pho 2013 Hogbin on Woodturning: Pattern from Process, The Center for Art in Wood Museum Store, September 19 – October 21, 2013 The exhibition Pattern from Process presents objects created for the instructional publication titled Hogbin on Woodturning. The 14 objects by Stephen Hogbin in the publication are represented in the exhibition with related material. Reading about the projects included in the publication and seeing the object will help students, educators, and woodworkers develop a clearer understanding of the construction and final quality of their work. Exhibited Artist: Stephen Hogbin 2013 allTURNatives: Form + Spirit 2013, The Center for Art in Wood, August 2 – October 12, 2013 Celebrating the 18th year of the International Turning Exchange Residency (ITE) program, the Center is proud to host the international artists, photojournalist and scholar who worked together for 2 months at the UArts in Philadelphia and explored new directions in their work.