Original Contributions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cranial Nerve Palsy

Cranial Nerve Palsy What is a cranial nerve? Cranial nerves are nerves that lead directly from the brain to parts of our head, face, and trunk. There are 12 pairs of cranial nerves and some are involved in special senses (sight, smell, hearing, taste, feeling) while others control muscles and glands. Which cranial nerves pertain to the eyes? The second cranial nerve is called the optic nerve. It sends visual information from the eye to the brain. The third cranial nerve is called the oculomotor nerve. It is involved with eye movement, eyelid movement, and the function of the pupil and lens inside the eye. The fourth cranial nerve is called the trochlear nerve and the sixth cranial nerve is called the abducens nerve. They each innervate an eye muscle involved in eye movement. The fifth cranial nerve is called the trigeminal nerve. It provides facial touch sensation (including sensation on the eye). What is a cranial nerve palsy? A palsy is a lack of function of a nerve. A cranial nerve palsy may cause a complete or partial weakness or paralysis of the areas served by the affected nerve. In the case of a cranial nerve that has multiple functions (such as the oculomotor nerve), it is possible for a palsy to affect all of the various functions or only some of the functions of that nerve. What are some causes of a cranial nerve palsy? A cranial nerve palsy can occur due to a variety of causes. It can be congenital (present at birth), traumatic, or due to blood vessel disease (hypertension, diabetes, strokes, aneurysms, etc). -

Cerebellar Ataxia

CEREBELLAR ATAXIA Dr. Waqar Saeed Ziauddin Medical University, Karachi, Pakistan What is Ataxia? ■ Derived from a Greek word, ‘A’ : not, ‘Taxis’ : orderly Ataxia is defined as an inability to maintain normal posture and smoothness of movement. Types of Ataxia ■ Cerebellar Ataxia ■ Sensory Ataxia ■ Vestibular Ataxia Cerebellar Ataxia Cerebrocerebellum Spinocerebellum Vestibulocerebellum Vermis Planning and Equilibrium balance Posture, limb and initiating and posture eye movements movements Limb position, touch and pressure sensation Limb ataxia, Eye movement dysdiadochokinesia, disorders, Truncal and gait Dysmetria dysarthria nystagmus, VOR, ataxia hypotonia postural and gait. Gait ataxia Types of Cerebellar Ataxia • Vascular Acute Ataxia • Medications and toxins • Infectious etiologies • Atypical Infectious agents • Autoimmune disorders • Primary or metastatic tumors Subacute Ataxia • Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration • Alcohol abuse and Vitamin deficiencies • Systemic disorders • Autosomal Dominant Chronic • Autosomal recessive Progressive • X linked ataxias • Mitochondrial • Sporadic neurodegenerative diseases Vascular Ataxia ▪ Benedikt Syndrome It is a rare form of posterior circulation stroke of the brain. A lesion within the tegmentum of the midbrain can produce Benedikt Syndrome. Disease is characterized by ipsilateral third nerve palsy with contralateral hemitremor. Superior cerebellar peduncle and/or red nucleus damage in Benedikt Syndrome can further lead in to contralateral cerebellar hemiataxia. ▪ Wallenberg Syndrome In -

Congenital Oculomotor Palsy: Associated Neurological and Ophthalmological Findings

CONGENITAL OCULOMOTOR PALSY: ASSOCIATED NEUROLOGICAL AND OPHTHALMOLOGICAL FINDINGS M. D. TSALOUMAS1 and H. E. WILLSHA W2 Birmingham SUMMARY In our group of patients we found a high incidence Congenital fourth and sixth nerve palsies are rarely of neurological abnormalities, in some cases asso associated with other evidence of neurological ahnor ciated with abnormal findings on CT scanning. mality, but there have been conflicting reports in the Aberrant regeneration, preferential fixation with literature on the associations of congenital third nerve the paretic eye, amblyopia of the non-involved eye palsy. In order to clarify the situation we report a series and asymmetric nystagmus have all been reported as 1 3 7 of 14 consecutive cases presenting to a paediatric associated ophthalmic findings. - , -9 However, we tertiary referral service over the last 12 years. In this describe for the first time a phenomenon of digital lid series of children, 5 had associated neurological elevation to allow fixation with the affected eye. Two abnormalities, lending support to the view that con children demonstrated this phenomenon and in each genital third nerve palsy is commonly a manifestation of case the accompanying neurological defect was widespread neurological damage. We also describe for profound. the first time a phenomenon of digital lid elevation to allow fixation with the affected eye. Two children demonstrated this phenomenon and in each case the PATIENTS AND METHODS accompanying neurological defect was profound. The Fourteen children (8 boys, 6 girls) with a diagnosis of frequency and severity of associated deficits is analysed, congenital oculomotor palsy presented to our paed and the mechanism of fixation with the affected eye is iatric tertiary referral centre over the 12 years from discussed. -

Canine Red Eye Elizabeth Barfield Laminack, DVM; Kathern Myrna, DVM, MS; and Phillip Anthony Moore, DVM, Diplomate ACVO

PEER REVIEWED Clinical Approach to the CANINE RED EYE Elizabeth Barfield Laminack, DVM; Kathern Myrna, DVM, MS; and Phillip Anthony Moore, DVM, Diplomate ACVO he acute red eye is a common clinical challenge for tion of the deep episcleral vessels, and is characterized general practitioners. Redness is the hallmark of by straight and immobile episcleral vessels, which run Tocular inflammation; it is a nonspecific sign related 90° to the limbus. Episcleral injection is an external to a number of underlying diseases and degree of redness sign of intraocular disease, such as anterior uveitis and may not reflect the severity of the ocular problem. glaucoma (Figures 3 and 4). Occasionally, episcleral Proper evaluation of the red eye depends on effective injection may occur in diseases of the sclera, such as and efficient diagnosis of the underlying ocular disease in episcleritis or scleritis.1 order to save the eye’s vision and the eye itself.1,2 • Corneal Neovascularization » Superficial: Long, branching corneal vessels; may be SOURCE OF REDNESS seen with superficial ulcerative (Figure 5) or nonul- The conjunctiva has small, fine, tortuous and movable vessels cerative keratitis (Figure 6) that help distinguish conjunctival inflammation from deeper » Focal deep: Straight, nonbranching corneal vessels; inflammation (see Ocular Redness algorithm, page 16). indicates a deep corneal keratitis • Conjunctival hyperemia presents with redness and » 360° deep: Corneal vessels in a 360° pattern around congestion of the conjunctival blood vessels, making the limbus; should arouse concern that glaucoma or them appear more prominent, and is associated with uveitis (Figure 4) is present1,2 extraocular disease, such as conjunctivitis (Figure 1). -

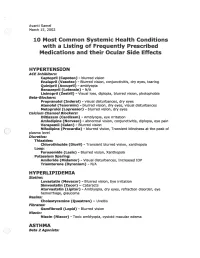

2002 Samel 10 Most Common Systemic Health Conditions with A

Avanti Samel / March 15, 2002 10 Most Common Systemic Health Conditions with a Listing of Frequently Prescribed Medications and their Ocular Side Effects HYPERTENSION ACE Inhibitors: Captopril (Capoten}- blurred vision Enalapril (Vasotec) - Blurred vision, conjunctivitis, dry eyes, tearing Quinipril (Accupril)- amblyopia Benazepril (Lotensin)- N/A Lisinopril (Zestril) - Visual loss, diplopia, blurred vision, photophobia Beta-Blockers: Propranolol (Inderal)- visual disturbances, dry eyes Atenolol (Tenormin)- blurred vision, dry eyes, visual disturbances Metoprolol (Lopressor) - blurred vision, dry eyes calcium Channel Blockers: Diltiazem (Cardizem)- Amblyopia, eye irritation Amlodipine (Norvasc)- abnormal vision, conjunctivitis, diplopia, eye pain Verapamil (Calan)- Blurred vision Nifedipine (Procardia) - blurred vision, Transient blindness at the peak of plasma level · Diuretics: Thiazides: Chlorothiazide (Diuril) - Transient blurred vision, xanthopsia Loop: Furosemide (Lasix) - Blurred vision, Xanthopsia Potassium Sparing: Amiloride (Midamor) - Visual disturbances, Increased lOP Triamterene (Dyrenium)- N/A HYPERLIPIDEMIA Statins: Lovastatin (Mevacor) - Blurred vision, Eye irritation Simvastatin (Zocor)- Cataracts Atorvastatin (Lipitor)- Amblyopia, dry eyes, refraction disorder, eye hemorrhage, glaucoma Resins: Cholestyramine (Questran)- Uveitis Fibrates: Gemfibrozil (Lopid)- Blurred vision Niacin: Niacin (Niacor) - Toxic amblyopia, cystoid macular edema ASTHMA ( ) Beta 2 Agonists: Albuterol (Proventil) - N/A ( Salmeterol (Serevent)- -

Topical Diagnosis in Neurology

V Preface In 2005 we publishedacomplete revision of Duus’ Although the book will be useful to advanced textbook of topical diagnosis in neurology,the first students, also physicians or neurobiologists inter- newedition since the death of its original author, estedinenriching their knowledge of neu- Professor PeterDuus, in 1994.Feedbackfromread- roanatomywith basic information in neurology,oR ers wasextremelypositive and the book wastrans- for revision of the basics of neuroanatomywill lated intonumerous languages, proving that the benefit even morefromit. conceptofthis book wasasuccessful one: combin- This book does notpretend to be atextbook of ing an integrated presentation of basic neu- clinical neurology.That would go beyond the scope roanatomywith the subject of neurological syn- of the book and also contradict the basic concept dromes, including modern imaging techniques. In described above.Firstand foremostwewant to de- this regard we thank our neuroradiology col- monstratehow,onthe basis of theoretical ana- leagues, and especiallyDr. Kueker,for providing us tomical knowledge and agood neurological exami- with images of very high quality. nation, it is possible to localize alesion in the In this fifthedition of “Duus,” we have preserved nervous system and come to adecision on further the remarkablyeffective didactic conceptofthe diagnostic steps. The cause of alesion is initially book,whichparticularly meets the needs of medi- irrelevant for the primarytopical diagnosis, and cal students. Modern medical curricula requirein- elucidation of the etiology takes place in asecond tegrative knowledge,and medical studentsshould stage. Our book contains acursoryoverviewofthe be taught howtoapplytheoretical knowledge in a major neurologicaldisorders, and it is notintended clinical settingand, on the other hand, to recognize to replace the systematic and comprehensive clinical symptoms by delving intotheir basic coverage offeredbystandardneurological text- knowledge of neuroanatomyand neurophysiology. -

THE SYNDROMES of the ARTERIES of the BRAIN and SPINAL CORD Part 1 by LESLIE G

65 Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.29.328.65 on 1 February 1953. Downloaded from THE SYNDROMES OF THE ARTERIES OF THE BRAIN AND SPINAL CORD Part 1 By LESLIE G. KILOH, M.D., M.R.C.P., D.P.M. First Assistant in the Joint Department of Psychological Medicine, Royal Victoria Infirmary and University of Durham Introduction general circulatory efficiency at the time of the Little interest is shown at present in the syn- catastrophe is of the greatest importance. An dromes of the arteries of the brain and spinal cord, occlusion, producing little effect in the presence of and this perhaps is related to the tendency to a normal blood pressure, may cause widespread minimize the importance of cerebral localization. pathological changes if hypotension co-exists. Yet these syndromes are far from being fully A marked discrepancy has been noted between elucidated and understood. It must be admitted the effects of ligation and of spontaneous throm- that in many cases precise localization is often of bosis of an artery. The former seldom produces little more than academic interest and ill effects whilst the latter frequently determines provides Protected by copyright. nothing but a measure of personal satisfaction to infarction. This is probably due to the tendency the physician. But it is worth recalling that the of a spontaneous thrombus to extend along the detailed study of the distribution of the bronchi affected vessel, sealing its branches and blocking and of the pathological anatomy of congenital its collateral circulation, and to the fact that the abnormalities of the heart, was similarly neglected arterial disease is so often generalized. -

GAZE and AUTONOMIC INNERVATION DISORDERS Eye64 (1)

GAZE AND AUTONOMIC INNERVATION DISORDERS Eye64 (1) Gaze and Autonomic Innervation Disorders Last updated: May 9, 2019 PUPILLARY SYNDROMES ......................................................................................................................... 1 ANISOCORIA .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Benign / Non-neurologic Anisocoria ............................................................................................... 1 Ocular Parasympathetic Syndrome, Preganglionic .......................................................................... 1 Ocular Parasympathetic Syndrome, Postganglionic ........................................................................ 2 Horner Syndrome ............................................................................................................................. 2 Etiology of Horner syndrome ................................................................................................ 2 Localizing Tests .................................................................................................................... 2 Diagnosis ............................................................................................................................... 3 Flow diagram for workup of anisocoria ........................................................................................... 3 LIGHT-NEAR DISSOCIATION ................................................................................................................. -

Anatomy of the Extraneural Blood Supply to the Intracranial

British Journal of Ophthalmology 1996; 80: 177-181 177 the extraneural blood to the Anatomy of supply Br J Ophthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.80.2.177 on 1 February 1996. Downloaded from intracranial oculomotor nerve Mark Cahill, John Bannigan, Peter Eustace Abstract have since been classified as extraneural vessels Aims-An anatomical study was under- as they arise from outside the nerve and ramify taken to determine the extraneural blood on the surface ofthe nerve. In 1965, Parkinson supply to the intracranial oculomotor attempted to demonstrate and name the nerve. branches of the intracavernous internal carotid Methods-Human tissue blocks contain- artery.3 One of these branches, the newly titled ing brainstem, cranial nerves II-VI, body meningohypophyseal trunk was seen to pro- of sphenoid, and associated cavernous vide a nutrient arteriole to the oculomotor sinuses were obtained, injected with con- nerve in the majority of dissections. The infe- trast material, and dissected using a rior hypophyseal artery was also seen to arise stereoscopic microscope. from the meningohypophyseal trunk. Seven Results-Eleven oculomotor nerves were years earlier McConnell had demonstrated dissected, the intracranial part being that this vessel provided a large portion of the divided into proximal, middle, and distal pituitary blood supply.4 (intracavernous) parts. The proximal part Asbury and colleagues provided further of the intracranial oculomotor nerve anatomical detail in 1970.5 They set out to received extraneural nutrient arterioles explain the clinical findings of diabetic oph- from thalamoperforating arteries in all thalmoplegia on a pathological basis. Using a specimens and in six nerves this blood serial section technique, they demonstrated an supply was supplemented by branches intraneural network of small arterioles within from other brainstem vessels. -

Intermittent Mydriasis Associated with Carotid Vascular Occlusion

Eye (2018) 32, 457–459 © 2018 Macmillan Publishers Limited, part of Springer Nature. All rights reserved 0950-222X/18 www.nature.com/eye 1,2 2 2 Intermittent mydriasis PD Chamberlain , A Sadaka , S Berry CASE SERIES 1,2,3,4,5,6 associated with carotid and AG Lee vascular occlusion Abstract the literature as benign episodic pupillary dilation or BEUM. We report two patients with Purpose To describe two cases of 1 stereotyped, intermittent, neurologically acquired occlusive disease of the ipsilateral ICA Department of Ophthalmology, Blanton isolated, unilateral mydriasis in patients who developed multiple, stereotyped, neurologically isolated, transient episodes of Eye Institute, Houston with a history of acquired internal carotid Methodist Hospital, artery (ICA) occlusive disease on the mydriasis consistent with BEUM. We discuss the Houston, TX, USA ipsilateral side. possible mechanisms, differential diagnosis and 2 Patients Two patients with intermittent recommended evaluation for atypical cases for Department of episodic mydriasis. Ophthalmology, Baylor mydriasis. College of Medicine, Methods Case Series. Houston, TX, USA Results Case one: A 78-year-old man Case one 3 experienced 10 episodes of intermittent, Departments of Ophthalmology, Neurology, unilateral, and painless mydriasis in the left A 78-year-old man presented with 10 episodes of and Neurosurgery, Weill stereotyped, intermittent, unilateral, painless eye and had 100% occlusion of the left ICA Cornell Medical College, artery due to atherosclerotic disease. Case two: pupillary dilation of the left eye (OS) lasting New York, NY, USA A 26-year-old woman with history of migraine minutes to hours at a time without diplopia or fi 4Department of developed new painless, intermittent episodes ptosis. -

Crossed Brainstem Syndrome Revealing

Beucler et al. BMC Neurology (2021) 21:204 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-021-02223-7 CASE REPORT Open Access Crossed brainstem syndrome revealing bleeding brainstem cavernous malformation: an illustrative case Nathan Beucler1,2* , Sébastien Boissonneau1,3, Aurélia Ruf4, Stéphane Fuentes1, Romain Carron3,5 and Henry Dufour1,6 Abstract Background: Since the nineteenth century, a great variety of crossed brainstem syndromes (CBS) have been described in the medical literature. A CBS typically combines ipsilateral cranial nerves deficits to contralateral long tracts involvement such as hemiparesis or hemianesthesia. Classical CBS seem in fact not to be so clear-cut entities with up to 20% of patients showing different or unnamed combinations of crossed symptoms. In terms of etiologies, acute brainstem infarction predominates but CBS secondary to hemorrhage, neoplasm, abscess, and demyelination have been described. The aim of this study was to assess the proportion of CBS caused by a bleeding episode arising from a brainstem cavernous malformation (BCM) reported in the literature. Case presentation: We present the case of a typical Foville syndrome in a 65-year-old man that was caused by a pontine BCM with extralesional bleeding. Following the first bleeding episode, a conservative management was decided but the patient had eventually to be operated on soon after the second bleeding event. Discussion: A literature review was conducted focusing on the five most common CBS (Benedikt, Weber, Foville, Millard-Gubler, Wallenberg) on Medline database from inception to 2020. According to the literature, hemorrhagic BCM account for approximately 7 % of CBS. Microsurgical excision may be indicated after the second bleeding episode but needs to be carefully weighted up against the risks of the surgical procedure and openly discussed with the patient. -

High-Yield Neuroanatomy

LWBK110-3895G-FM[i-xviii].qxd 8/14/08 5:57 AM Page i Aptara Inc. High-Yield TM Neuroanatomy FOURTH EDITION LWBK110-3895G-FM[i-xviii].qxd 8/14/08 5:57 AM Page ii Aptara Inc. LWBK110-3895G-FM[i-xviii].qxd 8/14/08 5:57 AM Page iii Aptara Inc. High-Yield TM Neuroanatomy FOURTH EDITION James D. Fix, PhD Professor Emeritus of Anatomy Marshall University School of Medicine Huntington, West Virginia With Contributions by Jennifer K. Brueckner, PhD Associate Professor Assistant Dean for Student Affairs Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology University of Kentucky College of Medicine Lexington, Kentucky LWBK110-3895G-FM[i-xviii].qxd 8/14/08 5:57 AM Page iv Aptara Inc. Acquisitions Editor: Crystal Taylor Managing Editor: Kelley Squazzo Marketing Manager: Emilie Moyer Designer: Terry Mallon Compositor: Aptara Fourth Edition Copyright © 2009, 2005, 2000, 1995 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a Wolters Kluwer business. 351 West Camden Street 530 Walnut Street Baltimore, MD 21201 Philadelphia, PA 19106 Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including as photocopies or scanned-in or other electronic copies, or utilized by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the copyright owner, except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Materials appearing in this book prepared by individuals as part of their official duties as U.S. government employees are not covered by the above-mentioned copyright. To request permission, please contact Lippincott Williams & Wilkins at 530 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106, via email at [email protected], or via website at http://www.lww.com (products and services).