Thesis Addressing the Cause: an Analysis of Suicide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Haqqani Network in Kurram the Regional Implications of a Growing Insurgency

May 2011 The haQQani NetworK in KURR AM THE REGIONAL IMPLICATIONS OF A GROWING INSURGENCY Jeffrey Dressler & Reza Jan All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ©2011 by the Institute for the Study of War and AEI’s Critical Threats Project Cover image courtesy of Dr. Mohammad Taqi. the haqqani network in kurram The Regional Implications of a Growing Insurgency Jeffrey Dressler & Reza Jan A Report by the Institute for the Study of War and AEI’s Critical Threats Project ACKNOWLEDGEMENts This report would not have been possible without the help and hard work of numerous individuals. The authors would like to thank Alex Della Rocchetta and David Witter for their diligent research and critical support in the production of the report, Maggie Rackl for her patience and technical skill with graphics and design, and Marisa Sullivan and Maseh Zarif for their keen insight and editorial assistance. The authors would also like to thank Kim and Fred Kagan for their necessary inspiration and guidance. As always, credit belongs to many, but the contents of this report represent the views of the authors alone. taBLE OF CONTENts Introduction.....................................................................................1 Brief History of Kurram Agency............................................................1 The Mujahideen Years & Operation Enduring Freedom .............................. 2 Surge of Sectarianism in Kurram ...........................................................4 North Waziristan & The Search for New Sanctuary.....................................7 -

Afghan Opiate Trade 2009.Indb

ADDICTION, CRIME AND INSURGENCY The transnational threat of Afghan opium UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna ADDICTION, CRIME AND INSURGENCY The transnational threat of Afghan opium Copyright © United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), October 2009 Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the UNODC Studies and Threat Analysis Section (STAS), in the framework of the UNODC Trends Monitoring and Analysis Programme/Afghan Opiate Trade sub-Programme, and with the collaboration of the UNODC Country Office in Afghanistan and the UNODC Regional Office for Central Asia. UNODC field offices for East Asia and the Pacific, the Middle East and North Africa, Pakistan, the Russian Federation, Southern Africa, South Asia and South Eastern Europe also provided feedback and support. A number of UNODC colleagues gave valuable inputs and comments, including, in particular, Thomas Pietschmann (Statistics and Surveys Section) who reviewed all the opiate statistics and flow estimates presented in this report. UNODC is grateful to the national and international institutions which shared their knowledge and data with the report team, including, in particular, the Anti Narcotics Force of Pakistan, the Afghan Border Police, the Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan and the World Customs Organization. Thanks also go to the staff of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan and of the United Nations Department of Safety and Security, Afghanistan. Report Team Research and report preparation: Hakan Demirbüken (Lead researcher, Afghan -

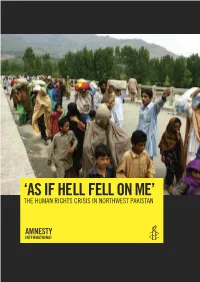

'As If Hell Fell On

‘a s if h ell fel l on m e’ THE HUmAn rIgHTS CrISIS In norTHWEST PAKISTAn amnesty international is a global movement of 2.8 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universal Declaration of human rights and other international human rights standards. we are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. amnesty international Publications first published in 2010 by amnesty international Publications international secretariat Peter Benenson house 1 easton street london wc1X 0Dw united kingdom www.amnesty.org © amnesty international Publications 2010 index: asa 33/004/2010 original language: english Printed by amnesty international, international secretariat, united kingdom all rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. for copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. Front and back cover photo s: families flee fighting between the Taleban and Pakistani government forces in the maidan region of lower Dir, northwest -

Pakistan Response Towards Terrorism: a Case Study of Musharraf Regime

PAKISTAN RESPONSE TOWARDS TERRORISM: A CASE STUDY OF MUSHARRAF REGIME By: SHABANA FAYYAZ A thesis Submitted to the University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Political Science and International Studies The University of Birmingham May 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The ranging course of terrorism banishing peace and security prospects of today’s Pakistan is seen as a domestic effluent of its own flawed policies, bad governance, and lack of social justice and rule of law in society and widening gulf of trust between the rulers and the ruled. The study focused on policies and performance of the Musharraf government since assuming the mantle of front ranking ally of the United States in its so called ‘war on terror’. The causes of reversal of pre nine-eleven position on Afghanistan and support of its Taliban’s rulers are examined in the light of the geo-strategic compulsions of that crucial time and the structural weakness of military rule that needed external props for legitimacy. The flaws of the response to the terrorist challenges are traced to its total dependence on the hard option to the total neglect of the human factor from which the thesis develops its argument for a holistic approach to security in which the people occupy a central position. -

Nimroz Rapid Drought Assessment Zaranj, Kang and Chakhansoor Districts Conducted August 21St-22Nd 2013

Nimroz Rapid Drought Assessment Zaranj, Kang and Chakhansoor Districts Conducted August 21st-22nd 2013 Figure 1 Dead livestock in Kang district Figure 2 Nimroz district map Relief International in Nimroz Relief International (RI) is a humanitarian, non‐profit, non‐sectarian agency that provides emergency relief, rehabilitation, and development interventions throughout the world. Since 2001, RI has supported a wide array of relief and development interventions throughout Afghanistan. RI programs focus on community participation, ensuring sustainability and helping communities establish a sense of ownership over all stages of the project cycle. Relief International has been working in Nimroz province since 2007, when RI took over implementation of the National Solidarity Program, as well as staff and offices, from Ockenden International. Through more than five years of work in partnership with Nimroz communities, RI has formed deep connections with communities, government, and other stakeholders such as UN agencies. RI has offices and is currently working in all districts of Nimroz, except for the newly added Delaram district (formerly belonging to Farah Province). RI has recently completed an ECHO WASH and shelter program and a DFID funded local governance program , and is currently implementing the National Solidarity Program and a food security and livelihoods program in the province. Nimroz General Information related to Drought Nimroz province is the most South Westerly Province of Afghanistan bordering Iran and Pakistan. The provincial capital is Zaranj, located in the west on the Iranian border. The population is estimated at 350,000 although, as for the rest of Afghanistan, no exact demographic data exists.1 There has been a flow of returnees from Iran over the last years, and the provincial capital has also grown due to internal migration. -

Länderinformationen Afghanistan Country

Staatendokumentation Country of Origin Information Afghanistan Country Report Security Situation (EN) from the COI-CMS Country of Origin Information – Content Management System Compiled on: 17.12.2020, version 3 This project was co-financed by the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund Disclaimer This product of the Country of Origin Information Department of the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum was prepared in conformity with the standards adopted by the Advisory Council of the COI Department and the methodology developed by the COI Department. A Country of Origin Information - Content Management System (COI-CMS) entry is a COI product drawn up in conformity with COI standards to satisfy the requirements of immigration and asylum procedures (regional directorates, initial reception centres, Federal Administrative Court) based on research of existing, credible and primarily publicly accessible information. The content of the COI-CMS provides a general view of the situation with respect to relevant facts in countries of origin or in EU Member States, independent of any given individual case. The content of the COI-CMS includes working translations of foreign-language sources. The content of the COI-CMS is intended for use by the target audience in the institutions tasked with asylum and immigration matters. Section 5, para 5, last sentence of the Act on the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum (BFA-G) applies to them, i.e. it is as such not part of the country of origin information accessible to the general public. However, it becomes accessible to the party in question by being used in proceedings (party’s right to be heard, use in the decision letter) and to the general public by being used in the decision. -

Mapping Pakistan's Internal Dynamics

the national bureau of asian research nbr special report #55 | february 2016 mapping pakistan’s internal dynamics Implications for State Stability and Regional Security By Mumtaz Ahmad, Dipankar Banerjee, Aryaman Bhatnagar, C. Christine Fair, Vanda Felbab-Brown, Husain Haqqani, Mahin Karim, Tariq A. Karim, Vivek Katju, C. Raja Mohan, Matthew J. Nelson, and Jayadeva Ranade cover 2 NBR Board of Directors Charles W. Brady George Davidson Tom Robertson (Chairman) Vice Chairman, M&A, Asia-Pacific Vice President and Chairman Emeritus HSBC Holdings plc Deputy General Counsel Invesco LLC Microsoft Corporation Norman D. Dicks John V. Rindlaub Senior Policy Advisor Gordon Smith (Vice Chairman and Treasurer) Van Ness Feldman LLP Chief Operating Officer President, Asia Pacific Exact Staff, Inc. Wells Fargo Richard J. Ellings President Scott Stoll George F. Russell Jr. NBR Partner (Chairman Emeritus) Ernst & Young LLP Chairman Emeritus R. Michael Gadbaw Russell Investments Distinguished Visiting Fellow David K.Y. Tang Institute of International Economic Law, Managing Partner, Asia Karan Bhatia Georgetown University Law Center K&L Gates LLP Vice President & Senior Counsel International Law & Policy Ryo Kubota Tadataka Yamada General Electric Chairman, President, and CEO Venture Partner Acucela Inc. Frazier Healthcare Dennis Blair Chairman Melody Meyer President Sasakawa Peace Foundation USA Honorary Directors U.S. Navy (Ret.) Chevron Asia Pacific Exploration and Production Company Maria Livanos Cattaui Chevron Corporation Lawrence W. Clarkson Secretary General (Ret.) Senior Vice President International Chamber of Commerce Pamela S. Passman The Boeing Company (Ret.) President and CEO William M. Colton Center for Responsible Enterprise Thomas E. Fisher Vice President and Trade (CREATe) Senior Vice President Corporate Strategic Planning Unocal Corporation (Ret.) Exxon Mobil Corporation C. -

For Official Use Only 304Th MI Bn OSINT Team

For Official Use Only 304th MI Bn OSINT Team U.S. Army Intelligence Center 304th Military Intelligence Roundup-Compilation of Posted Taliban Statements & Publications from Battalion Extremist Blog & Web Postings Fort Huachuca, AZ 85613 12/23/08-04/23/09 LTC Monnard, Commanding This 304th MI Bn open source compilation is derived from news media, extremist OPEDS, Blogs, and websites. The compilation is a sample of recent claimed Taliban and affiliate statements and WWW postings. The compilation is based on open source information and is not processed Open Source Intelligence. Comment: The items within the document are broken down by date from 04/23/09-12/23/08. A consistent trend throughout the compilation is that multiple documents show that the Taliban is trying to coerce its culture, rules, and law on Pakistan, in addition to an attempted re-establishment of power in Afghanistan. The compilation also shows that the Taliban power base in Pakistan (in addition to Taliban elements in Afghanistan) pose a clear security threat to U.S. military operating in the region and beyond. The following Taliban and affiliate names are mentioned, interviewed, and/or quoted in this document (some names have been highlighted throughout the document and some of the names may represent Kunyas and/or multiple variations of a name.) • Taliban and Possible Affiliated Names o Abu Abad commander o Allama Iqbal o Al-Mulawi Dastakir o Baitullah Mehsud o Dr. Israr Ahmed o Gul Bahadur o Hakimullah Mehsud o Inamur Rahman o Izzat Khan o Malik Mahmood o Maulana Faqir Mohammad o Maulana Khalil o Maulana Sufi Mohammad o Mohamad Rasul o Mulla Mohammad Omar o Molvi Iqbal o Mulla Nazeer Ahmad o Mullah Nazeer Ahmed o Muslim Khan o Omar Farooq o Qari Mohammad Yousuf o Sayd Mohammad o Shafirullah Khan o Shah Dauran o Sirajuddin Haqqani o Umer Khalid o Zabihullah Mujahid 1 For Official Use Only 304th MI Bn OSINT Team Table of Contents SAMPLE OF AFGHANISTAN & PAKISTAN TALIBAN QUOTES IN THE MEDIA ............................................... -

Counterinsurgency in Pakistan

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY institution that helps improve policy and POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY decisionmaking through research and SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY analysis. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND Support RAND INFRASTRUCTURE Purchase this document WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Counterinsurgency in Pakistan Seth G. Jones, C. Christine Fair NATIONAL SECURITY RESEARCH DIVISION Project supported by a RAND Investment in People and Ideas This monograph results from the RAND Corporation’s Investment in People and Ideas program. -

The Threat of Talibanisation of Pakistan : a Case Study of Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and North West Frontier Province (NWFP)

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. The threat of talibanisation of Pakistan : a case study of federally administered tribal areas (FATA) and north west frontier province (NWFP) Syed Adnan Ali Shah Bukhari 2015 Syed Adnan Ali Shah Bukhari. (2015). The threat of talibanisation of Pakistan : a case study of federally administered tribal areas (FATA) and north west frontier province (NWFP). Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. http://hdl.handle.net/10356/65418 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/65418 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 15:33:34 SGT THE THREAT OF TALIBANISATION OF PAKISTAN: A CASE STUDY OF FEDERALLY ADMINISTERED TRIBAL AREAS (FATA) AND NORTH WEST FRONTIER PROVINCE (N.W.F.P.) SYED ADNAN ALI SHAH BUKHARI S. RAJARATNAM SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES Thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I want to extend my deepest gratitude to Professor Ahmed Saleh Hashim and Professor Rohan Gunaratna, who encouraged, guided and helped me through the course of this study. Without their guidance and supervision, I would not have been able to finish this study successfully. Professor Hashim deserves special thanks for helping me in laying out a theoretical foundation for the study. I take this opportunity to express my gratitude to Professor Ron Mathews, former Head of Studies at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), who was always instrumental and patient in motivating me to ensure my success. I would like to thank Arabinda Acharya, former Research Fellow, for guiding my research and helping me developing knowledge and understanding of the terrorism and counter-terrorism phenomenon. -

Tehrik-E-Taliban Pakistan

DIIS REPORT 2010:12 DIIS REPORT TEHRIK-E-TALIBAN PAKISTAN AN ATTEMPT TO DECONSTRUCT THE UMBRELLA ORGANIZATION AND THE REASONS FOR ITS GROWTH IN PAKISTAN’S NORTH-WEST Qandeel Siddique DIIS REPORT 2010:12 DIIS REPORT DIIS . DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 1 DIIS REPORT 2010:12 © Copenhagen 2010, Qandeel Siddique and DIIS Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover photo: Pakistani Taliban chief Hakimullah Mehsud promising future attacks on major U.S. cities and claiming responsibility for the attempted car bombing on Times Square, New York (AP Photo/IntelCenter) Cover: Anine Kristensen Layout: Allan Lind Jørgensen Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN 978-87-7605-419-9 Price: DKK 50.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk Hardcopies can be ordered at www.diis.dk Qandeel Siddique, MSc, Research Assistant, DIIS www.diis.dk/qsi 2 DIIS REPORT 2010:12 Contents Executive Summary 4 Acronyms 6 1. TTP Organization 7 2. TTP Background 14 3. TTP Ideology 20 4. Militant Map 29 4.1 The Waziristans 30 4.2 Bajaur 35 4.3 Mohmand Agency 36 4.4 Middle Agencies: Kurram, Khyber and Orakzai 36 4.5 Swat valley and Darra Adamkhel 39 4.6 Punjab and Sind 43 5. Child Recruitment, Media Propaganda 45 6. Financial Sources 52 7. Reasons for TTP Support and FATA and Swat 57 8. Conclusion 69 Appendix A. -

Afghanistan: Extremism & Terrorism

Afghanistan: Extremism & Terrorism On September 7, 2021, the Taliban officially announced the appointments within its caretaker government. At the helm of the movement is Haibatullah Akhundzada, who will serve as supreme leader. Mullah Muhammad Hassan was named the acting prime minister, with Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar and Mawlawi Abdul Salam Hanafi named deputy prime ministers. The top security post was given to Sirajuddin Haqqani, who will serve as acting minister of the interior, a role in which he will have extensive authority over policing and legal matters. Mawlawi Mohammad Yaqoob, who is the oldest son of Taliban founder Mullah Muhammad Omar, is named the acting defense minister. The government is exclusively male, with many positions filled with veterans from their hardline movement in the early nineties. (Sources: New York Times, Associated Press) The appointments came a month after the Taliban began its offensive against major Afghan cities on August 6, 2021. By August 16, the Taliban laid siege to the presidential palace and took complete control of Kabul, declaring the war in Afghanistan had ended. The last U.S. troops flew out of Kabul on August 30, ending a 20-year war that took the lives of 2,500 American troops and 240,000 Afghans and cost about $2 trillion. By the evening of August 30, 123,000 people were evacuated from Kabul. Before departing, U.S. troops destroyed more than 70 aircraft, dozens of armored vehicles, and disabled air defenses that were used to counteract jihadist attacks in the country. The final withdrawal of U.S. troops was not a celebration of a more secure Afghanistan, but marked the beginning of a new Taliban regime.