Militancy and the Social Structure Development in Pashtun Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mountstuart Elphinstone: an Anthropologist Before Anthropology

Mountstuart Elphinstone Mountstuart Elphinstone in South Asia: Pioneer of British Colonial Rule Shah Mahmoud Hanifi Print publication date: 2019 Print ISBN-13: 9780190914400 Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: September 2019 DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190914400.001.0001 Mountstuart Elphinstone An Anthropologist Before Anthropology M. Jamil Hanifi DOI:10.1093/oso/9780190914400.003.0003 Abstract and Keywords During 1809, Mountstuart Elphinstone and his team of researchers visited the Persianate "Kingdom of Caubul" in Peshawar in order to sign a defense treaty with the ruler of the kingdom, Shah Shuja, and to collect information for use by the British colonial government of India. During his four-month stay in Peshawar, and subsequent two years research in Poona, India, Elphinstone collected a vast amount of ethnographic information from his Persian-speaking informants, as well as historical texts about the ethnology of Afghanistan. Some of this information provided the material for his 1815 (1819, 1839, 1842) encyclopaedic "An Account of the Kingdom of Caubul" (AKC), which became the ethnographic bible for Euro-American writings about Afghanistan. Elphinstone's competence in Farsi, his subscription to the ideology of Scottish Enlightenment, the collaborative methodology of his ethnographic research, and the integrity of the ethnographic texts in his AKC, qualify him as a pioneer anthropologist—a century prior to the birth of the discipline of anthropology in Europe. Virtually all Euro-American academic and political writings about Afghanistan during the last two-hundred years are informed and influenced by Elphinstone's AKC. This essay engages several aspects of the ethnological legacy of AKC. Keywords: Afghanistan, Collaborative Research, Ethnography, Ethnology, National Character For centuries the space marked ‘Afghanistan’ in academic, political, and popular discourse existed as a buffer between and in the periphery of the Persian and Persianate Moghol empires. -

The Haqqani Network in Kurram the Regional Implications of a Growing Insurgency

May 2011 The haQQani NetworK in KURR AM THE REGIONAL IMPLICATIONS OF A GROWING INSURGENCY Jeffrey Dressler & Reza Jan All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ©2011 by the Institute for the Study of War and AEI’s Critical Threats Project Cover image courtesy of Dr. Mohammad Taqi. the haqqani network in kurram The Regional Implications of a Growing Insurgency Jeffrey Dressler & Reza Jan A Report by the Institute for the Study of War and AEI’s Critical Threats Project ACKNOWLEDGEMENts This report would not have been possible without the help and hard work of numerous individuals. The authors would like to thank Alex Della Rocchetta and David Witter for their diligent research and critical support in the production of the report, Maggie Rackl for her patience and technical skill with graphics and design, and Marisa Sullivan and Maseh Zarif for their keen insight and editorial assistance. The authors would also like to thank Kim and Fred Kagan for their necessary inspiration and guidance. As always, credit belongs to many, but the contents of this report represent the views of the authors alone. taBLE OF CONTENts Introduction.....................................................................................1 Brief History of Kurram Agency............................................................1 The Mujahideen Years & Operation Enduring Freedom .............................. 2 Surge of Sectarianism in Kurram ...........................................................4 North Waziristan & The Search for New Sanctuary.....................................7 -

Afghan Internationalism and the Question of Afghanistan's Political Legitimacy

This is a repository copy of Afghan internationalism and the question of Afghanistan's political legitimacy. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/126847/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Leake, E orcid.org/0000-0003-1277-580X (2018) Afghan internationalism and the question of Afghanistan's political legitimacy. Afghanistan, 1 (1). pp. 68-94. ISSN 2399-357X https://doi.org/10.3366/afg.2018.0006 This article is protected by copyright. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Edinburgh University Press on behalf of the American Institute of Afghanistan Studies in "Afghanistan". Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Afghan internationalism and the question of Afghanistan’s political legitimacy1 Abstract This article uses Afghan engagement with twentieth-century international politics to reflect on the fluctuating nature of Afghan statehood and citizenship, with a particular focus on Afghanistan’s political ‘revolutions’ in 1973 and 1978. -

The Pashtun Behavior Economy an Analysis of Decision Making in Tribal Society

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis and Dissertation Collection 2011-06 The Pashtun behavior economy an analysis of decision making in tribal society Holton, Jeremy W. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/5687 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS THE PASHTUN BEHAVIOR ECONOMY: AN ANALYSIS OF DECISION MAKING IN TRIBAL SOCIETY by Jeremy W. Holton June 2011 Thesis Advisor: Thomas H. Johnson Second Reader: Robert McNab Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 2011 Master‘s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE The Pashtun Behavior Economy: An Analysis of 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Decision Making in Tribal Society 6. AUTHOR(S) Jeremy W. Holton 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School REPORT NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943-5000 9. SPONSORING /MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

'Pashtunistan': the Challenge to Pakistan and Afghanistan

Area: Security & Defence - ARI 37/2008 Date: 2/4/2008 ‘Pashtunistan’: The Challenge to Pakistan and Afghanistan Selig S. Harrison * Theme: The increasing co-operation between Pashtun nationalist and Islamist forces against Punjabi domination could lead to the break-up of Pakistan and Afghanistan and the emergence of a new national entity: an ‘Islamic Pashtunistan’. Summary: The alarming growth of al-Qaeda and the Taliban in the Pashtun tribal region of north-western Pakistan and southern Afghanistan is usually attributed to the popularity of their messianic brand of Islam and to covert help from Pakistani intelligence agencies. But another, more ominous, reason also explains their success: their symbiotic relationship with a simmering Pashtun separatist movement that could lead to the unification of the estimated 41 million Pashtuns on both sides of the border, the break-up of Pakistan and Afghanistan, and the emergence of a new national entity, an ‘Islamic Pashtunistan’. This ARI examines the Pashtun claim for an independent territory, the historical and political roots of the Pashtun identity, the implications for the NATO- or Pakistani-led military operations in the area, the increasing co-operation between Pashtun nationalist and Islamist forces against Punjabi domination and the reasons why the Pashtunistan movement, long dormant, is slowly coming to life. Analysis: The alarming growth of al-Qaeda and the Taliban in the Pashtun tribal region of north-western Pakistan and southern Afghanistan is usually attributed to the popularity of their messianic brand of Islam and to covert help from Pakistani intelligence agencies. But another, more ominous reason also explains their success: their symbiotic relationship with a simmering Pashtun separatist movement that could lead to the unification of the estimated 41 million Pashtuns on both sides of the border, the break-up of Pakistan and Afghanistan, and the emergence of a new national entity, ‘Pashtunistan,’ under radical Islamist leadership. -

Afghan Opiate Trade 2009.Indb

ADDICTION, CRIME AND INSURGENCY The transnational threat of Afghan opium UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna ADDICTION, CRIME AND INSURGENCY The transnational threat of Afghan opium Copyright © United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), October 2009 Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the UNODC Studies and Threat Analysis Section (STAS), in the framework of the UNODC Trends Monitoring and Analysis Programme/Afghan Opiate Trade sub-Programme, and with the collaboration of the UNODC Country Office in Afghanistan and the UNODC Regional Office for Central Asia. UNODC field offices for East Asia and the Pacific, the Middle East and North Africa, Pakistan, the Russian Federation, Southern Africa, South Asia and South Eastern Europe also provided feedback and support. A number of UNODC colleagues gave valuable inputs and comments, including, in particular, Thomas Pietschmann (Statistics and Surveys Section) who reviewed all the opiate statistics and flow estimates presented in this report. UNODC is grateful to the national and international institutions which shared their knowledge and data with the report team, including, in particular, the Anti Narcotics Force of Pakistan, the Afghan Border Police, the Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan and the World Customs Organization. Thanks also go to the staff of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan and of the United Nations Department of Safety and Security, Afghanistan. Report Team Research and report preparation: Hakan Demirbüken (Lead researcher, Afghan -

'As If Hell Fell On

‘a s if h ell fel l on m e’ THE HUmAn rIgHTS CrISIS In norTHWEST PAKISTAn amnesty international is a global movement of 2.8 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universal Declaration of human rights and other international human rights standards. we are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. amnesty international Publications first published in 2010 by amnesty international Publications international secretariat Peter Benenson house 1 easton street london wc1X 0Dw united kingdom www.amnesty.org © amnesty international Publications 2010 index: asa 33/004/2010 original language: english Printed by amnesty international, international secretariat, united kingdom all rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. for copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. Front and back cover photo s: families flee fighting between the Taleban and Pakistani government forces in the maidan region of lower Dir, northwest -

Pakistan Response Towards Terrorism: a Case Study of Musharraf Regime

PAKISTAN RESPONSE TOWARDS TERRORISM: A CASE STUDY OF MUSHARRAF REGIME By: SHABANA FAYYAZ A thesis Submitted to the University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Political Science and International Studies The University of Birmingham May 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The ranging course of terrorism banishing peace and security prospects of today’s Pakistan is seen as a domestic effluent of its own flawed policies, bad governance, and lack of social justice and rule of law in society and widening gulf of trust between the rulers and the ruled. The study focused on policies and performance of the Musharraf government since assuming the mantle of front ranking ally of the United States in its so called ‘war on terror’. The causes of reversal of pre nine-eleven position on Afghanistan and support of its Taliban’s rulers are examined in the light of the geo-strategic compulsions of that crucial time and the structural weakness of military rule that needed external props for legitimacy. The flaws of the response to the terrorist challenges are traced to its total dependence on the hard option to the total neglect of the human factor from which the thesis develops its argument for a holistic approach to security in which the people occupy a central position. -

Representation of Pashtun Culture in Pashto Films Posters: a Semiotic Analysis

DOI: 10.31703/glr.2020(V-I).29 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/glr.2020(V-I).29 Citation: Mukhtar, Y., Iqbal, L., & Rehman, F. (2020). Representation of Pashtun Culture in Pashto Films Posters: A Semiotic Analysis. Global Language Review, V(I), 281-292. doi:10.31703/glr.2020(V-I).29 Yusra Mukhtar* Liaqat Iqbal† Faiza Rehman‡ p-ISSN: 2663-3299 e-ISSN: 2663-3841 L-ISSN: 2663-3299 Vol. V, No. I (Winter 2020) Pages: 281- 292 Representation of Pashtun Culture in Pashto Films Posters: A Semiotic Analysis Abstract: Introduction The purpose of the research is to investigate It is in the nature of human beings to infer meaning out of every the representation or misrepresentation of word they hear, every object they see and every act they observe. Pashtun culture through the study of It is because whatever we hear, see or observe may suggest different signs and to inspect that how these deeper and broader interpretation than its explicit signs relate to Pashtun culture by employing representation. All of these can be taken as distinct signs, semiotics as a tool. To achieve the goal, which is anything that indicates or is referred to as something twelve distinct Pashto film posters that were other than itself. Signs hold the meaning and convey it to the published during 2011-2017 were selected and categorized under poster design, interpreter for inferring meaning out of it; for example, the dressing, props and titles, as these aspects traffic lights direct the traffic without using verbal means of act as signs for depicting cultural insights. -

Mapping Pakistan's Internal Dynamics

the national bureau of asian research nbr special report #55 | february 2016 mapping pakistan’s internal dynamics Implications for State Stability and Regional Security By Mumtaz Ahmad, Dipankar Banerjee, Aryaman Bhatnagar, C. Christine Fair, Vanda Felbab-Brown, Husain Haqqani, Mahin Karim, Tariq A. Karim, Vivek Katju, C. Raja Mohan, Matthew J. Nelson, and Jayadeva Ranade cover 2 NBR Board of Directors Charles W. Brady George Davidson Tom Robertson (Chairman) Vice Chairman, M&A, Asia-Pacific Vice President and Chairman Emeritus HSBC Holdings plc Deputy General Counsel Invesco LLC Microsoft Corporation Norman D. Dicks John V. Rindlaub Senior Policy Advisor Gordon Smith (Vice Chairman and Treasurer) Van Ness Feldman LLP Chief Operating Officer President, Asia Pacific Exact Staff, Inc. Wells Fargo Richard J. Ellings President Scott Stoll George F. Russell Jr. NBR Partner (Chairman Emeritus) Ernst & Young LLP Chairman Emeritus R. Michael Gadbaw Russell Investments Distinguished Visiting Fellow David K.Y. Tang Institute of International Economic Law, Managing Partner, Asia Karan Bhatia Georgetown University Law Center K&L Gates LLP Vice President & Senior Counsel International Law & Policy Ryo Kubota Tadataka Yamada General Electric Chairman, President, and CEO Venture Partner Acucela Inc. Frazier Healthcare Dennis Blair Chairman Melody Meyer President Sasakawa Peace Foundation USA Honorary Directors U.S. Navy (Ret.) Chevron Asia Pacific Exploration and Production Company Maria Livanos Cattaui Chevron Corporation Lawrence W. Clarkson Secretary General (Ret.) Senior Vice President International Chamber of Commerce Pamela S. Passman The Boeing Company (Ret.) President and CEO William M. Colton Center for Responsible Enterprise Thomas E. Fisher Vice President and Trade (CREATe) Senior Vice President Corporate Strategic Planning Unocal Corporation (Ret.) Exxon Mobil Corporation C. -

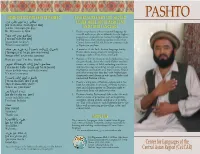

Pashto Five Reasons Why You Should Pashto Learn More About Pashtuns سالم

SOME USEFUL PHRASES IN PASHTO FIVE REASONS WHY YOU SHOULD PASHTO LEARN MORE ABOUT PASHTUNS سﻻم. زما نوم جان دئ. [saˈlɔːm zmɔː num ʤɔːn dǝɪ] Uzbeks are the most numerous Turkic /salām. zmā num jān dǝy./ AND THEIR LANGUAGE Hi. My name is John. 1. Pashto is spoken as a first or second language by people in Central Asia. They predomi- over 40 million people worldwide, but the highest nantly mostly live in Uzbekistan, a land- population of speakers are located in Afghanistan ستاسو نوم څه دئ؟ [ˈstɔːso num ʦǝ dǝɪ] and Pakistan, with smaller populations in other locked country of Central Asia that shares /stāso num ʦǝ dǝy?/ Central Asian and Middle Eastern countries such borders with Kazakhstan to the west and What is your name? as Tajikistan and Iran. north, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to the ,A member of the Indo-Iranian language family .2 تاسې څنګه یاست؟ زه ښه یم، مننه. [ˈʦǝŋgɒ jɔːst zǝ ʂɒ jǝm mɒˈnǝnɒ] Pashto shares many structural similarities to east, and Afghanistan and Turkmenistan /ʦǝnga yāst? zǝ ṣ̆ a yǝm, manǝna./ languages such as Dari, Farsi, and Tajiki. to the south. Many Uzbeks can also be How are you? I’m fine, thanks. 3. Because of US involvement with Afghanistan over found in Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, Kyr- the past decade, those who study Pashto can find careers in a variety of fields including translation gyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and the ستاسو دلیدو څخه خوشحاله شوم. [ˈstɔːso dǝˈliːdo ˈʦǝχa χoʃˈhɔːla ʃwǝm] and interpreting, consulting, foreign service and Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of /stāso dǝ-lido ʦǝxa xoš-hāla šwǝm./ intelligence, journalism, and many others. -

The Effects of Militancy and Military Operations on Pashtun Culture and Religion in FATA

ISSN: 2664-8148 (Online) LASSIJ Liberal Arts and Social Sciences International Journal Vol. 3, No. 1, (January-June) 2019, 73-82 Research Article www.lassij.org ___________________________________________________________________________ The Effects of Militancy and Military Operations on Pashtun Culture and Religion in FATA Surat Khan1*, Tayyab Wazir2 and Arif Khan3 1. Department of Political Science, Faculty of Social Sciences University of Peshawar, Pakistan. 2. Department of Defence & Strategic Studies, Quaid-e-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan. 3. Department of Political Science, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Buner, Pakistan. ………………………………………………………………………………………………… Abstract Two events in the last five decades proved to be disastrous for the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), now part of KP province: the USSR invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and ‘War on Terror' initiated by the US against militants in Afghanistan in 2001. After the incident of 9/11, FATA became the centre of global terrorism and emerged as the most dangerous place. Taliban’s rule was overthrown in Kabul, and they escaped and found refugees across the eastern border of Afghanistan with Pakistan. This paper aims at studying the emergence of Talibanization in FATA and its impacts on the local culture and religion. Furthermore, the research studies the effects of military operations on FATA’s cultural values and codes of life. Taliban, in FATA, while taking advantage of the local vulnerabilities and the state policy of appeasement, started expanding their roots and networks throughout the country. They conducted attacks on the civilians and security forces particularly when Pakistan joined the US ‘war on terror.’ Both the militancy and the military operations have left deep imprints thus affected the local culture, customs, values, and religious orientations in FATA.