The World's Most Poisonous Mushroom, Amanita Phalloides, Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Four Patients with Amanita Phalloides Poisoning CASE SERIE

CASE SERIE 353 Four patients with Amanita Phalloides poisoning S. Vanooteghem1, J. Arts2, S. Decock2, P. Pieraerts3, W. Meersseman4, C. Verslype1, Ph. Van Hootegem2 (1) Department of hepatology, UZ Leuven ; (2) Department of gastroenterology, AZ St-Lucas, Brugge ; (3) General Practitioner, Zedelgem ; (4) Department of internal medicine, UZ Leuven. Abstract because they developed stage 2 hepatic encephalopathy. With maximal supportive therapy, all patients gradually Mushroom poisoning by Amanita phalloides is a rare but poten- improved from day 3 and recovered without the need for tially fatal disease. The initial symptoms of nausea, vomiting, ab- dominal pain and diarrhea, which are typical for the intoxication, liver transplantation. They were discharged from the can be interpreted as a common gastro-enteritis. The intoxication hospital between 6 to 10 days after admission. can progress to acute liver and renal failure and eventually death. Recognizing the clinical syndrome is extremely important. In this case report, 4 patients with amatoxin intoxication who showed the Discussion typical clinical syndrome are described. The current therapy of amatoxin intoxication is based on small case series, and no ran- Among mushroom intoxications, amatoxin intoxica- domised controlled trials are available. The therapy of amatoxin intoxication consists of supportive care and medical therapy with tion accounts for 90% of all fatalities. Amatoxin poison- silibinin and N-acetylcysteine. Patients who develop acute liver fail- ing is caused by mushroom species belonging to the gen- ure should be considered for liver transplantation. (Acta gastro- era Amanita, Galerina and Lepiota. Amanita phalloides, enterol. belg., 2014, 77, 353-356). commonly known as the “death cap”, causes the majority Key words : amanita phalloides, mushroom poisoning, acute liver of fatal cases. -

Bur¯Aq Depicted As Amanita Muscaria in a 15Th Century Timurid-Illuminated Manuscript?

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Journal of Psychedelic Studies 3(2), pp. 133–141 (2019) DOI: 10.1556/2054.2019.023 First published online September 24, 2019 Bur¯aq depicted as Amanita muscaria in a 15th century Timurid-illuminated manuscript? ALAN PIPER* Independent Scholar, Newham, London, UK (Received: May 8, 2019; accepted: August 2, 2019) A series of illustrations in a 15th century Timurid manuscript record the mi’raj, the ascent through the seven heavens by Mohammed, the Prophet of Islam. Several of the illustrations depict Bur¯aq, the fabulous creature by means of which Mohammed achieves his ascent, with distinctive features of the Amanita muscaria mushroom. A. muscaria or “fly agaric” is a psychoactive mushroom used by Siberian shamans to enter the spirit world for the purposes of conversing with spirits or diagnosing and curing disease. Using an interdisciplinary approach, the author explores the routes by which Bur¯aq could have come to be depicted in this manuscript with the characteristics of a psychoactive fungus, when any suggestion that the Prophet might have had recourse to a drug to accomplish his spirit journey would be anathema to orthodox Islam. There is no suggestion that Mohammad’s night journey (isra) or ascent (mi’raj) was accomplished under the influence of a psychoactive mushroom or plant. Keywords: Mi’raj, Timurid, Central Asia, shamanism, Siberia, Amanita muscaria CULTURAL CONTEXT Bur¯aq depicted as Amanita muscaria in the mi’raj manscript The mi’raj manuscript In the Muslim tradition, the mi’raj was preceded by the isra or “Night Journey” during which Mohammed traveled An illustrated manuscript depicting, in a series of miniatures, overnight from Mecca to Jerusalem by means of a fabulous thesuccessivestagesofthemi’raj, the miraculous ascent of beast called Bur¯aq. -

Field Guide to Common Macrofungi in Eastern Forests and Their Ecosystem Functions

United States Department of Field Guide to Agriculture Common Macrofungi Forest Service in Eastern Forests Northern Research Station and Their Ecosystem General Technical Report NRS-79 Functions Michael E. Ostry Neil A. Anderson Joseph G. O’Brien Cover Photos Front: Morel, Morchella esculenta. Photo by Neil A. Anderson, University of Minnesota. Back: Bear’s Head Tooth, Hericium coralloides. Photo by Michael E. Ostry, U.S. Forest Service. The Authors MICHAEL E. OSTRY, research plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station, St. Paul, MN NEIL A. ANDERSON, professor emeritus, University of Minnesota, Department of Plant Pathology, St. Paul, MN JOSEPH G. O’BRIEN, plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, St. Paul, MN Manuscript received for publication 23 April 2010 Published by: For additional copies: U.S. FOREST SERVICE U.S. Forest Service 11 CAMPUS BLVD SUITE 200 Publications Distribution NEWTOWN SQUARE PA 19073 359 Main Road Delaware, OH 43015-8640 April 2011 Fax: (740)368-0152 Visit our homepage at: http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/ CONTENTS Introduction: About this Guide 1 Mushroom Basics 2 Aspen-Birch Ecosystem Mycorrhizal On the ground associated with tree roots Fly Agaric Amanita muscaria 8 Destroying Angel Amanita virosa, A. verna, A. bisporigera 9 The Omnipresent Laccaria Laccaria bicolor 10 Aspen Bolete Leccinum aurantiacum, L. insigne 11 Birch Bolete Leccinum scabrum 12 Saprophytic Litter and Wood Decay On wood Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus populinus (P. ostreatus) 13 Artist’s Conk Ganoderma applanatum -

Advances in Anticancer Antibody-Drug Conjugates and Immunotoxins

Send Orders for Reprints to [email protected] Recent Patents on Anti-Cancer Drug Discovery, 2014, 9, 35-65 35 Advances in Anticancer Antibody-Drug Conjugates and Immunotoxins Franco Dosio1,*, Barbara Stella1, Sofia Cerioni1, Daniela Gastaldi2 and Silvia Arpicco1 1Dipartimento di Scienza e Tecnologia del Farmaco, University of Torino, Torino, I-10125, Italy; 2Dipartimento di Bio- tecnologie Molecolari e Scienze per la Salute, University of Torino, Torino, I-10125, Italy Received: December 13, 2012; Accepted: February 21, 2013; Revised: March 7, 2013 Abstract: Antibody-delivered drugs and toxins are poised to become important classes of cancer therapeutics. These bio- pharmaceuticals have potential in this field, as they can selectively direct highly potent cytotoxic agents to cancer cells that present tumor-associated surface markers, thereby minimizing systemic toxicity. The activity of some conjugates is of particular interest receiving increasing attention, thanks to very promising clinical trial results in hematologic cancers. Over twenty antibody-drug conjugates and eight immunotoxins in clinical trials as well as some recently approved drugs, support the maturity of this approach. This review focuses on recent advances in the development of these two classes of biopharmaceuticals: conventional toxins and anticancer drugs, together with their mechanisms of action. The processes of conjugation and purification, as reported in the literature and in several patents, are discussed and the most relevant results in clinical trials are listed. Innovative technologies and preliminary results on novel drugs and toxins, as reported in the literature and in recently-published patents (up to February 2013) are lastly examined. Keywords: Antibody drug conjugate, anticancer agents, auristatins immunotoxin, calicheamicins, cross-linkers, duocarmycins, maytansinoids. -

AMATOXIN MUSHROOM POISONING in NORTH AMERICA 2015-2016 by Michael W

VOLUME 57: 4 JULY-AUGUST 2017 www.namyco.org AMATOXIN MUSHROOM POISONING IN NORTH AMERICA 2015-2016 By Michael W. Beug: Chair, NAMA Toxicology Committee Assessing the degree of amatoxin mushroom poisoning in North America is very challenging. Understanding the potential for various treatment practices is even more daunting. Although I have been studying mushroom poisoning for 45 years now, my own views on potential best treatment practices are still evolving. While my training in enzyme kinetics helps me understand the literature about amatoxin poisoning treatments, my lack of medical training limits me. Fortunately, critical comments from six different medical doctors have been incorporated in this article. All six, each concerned about different aspects in early drafts, returned me to the peer reviewed scientific literature for additional reading. There remains no known specific antidote for amatoxin poisoning. There have not been any gold standard double-blind placebo controlled studies. There never can be. When dealing with a potentially deadly poisoning (where in many non-western countries the amatoxin fatality rate exceeds 50%) treating of half of all poisoning patients with a placebo would be unethical. Using amatoxins on large animals to test new treatments (theoretically a great alternative) has ethical constraints on the experimental design that would most likely obscure the answers researchers sought. We must thus make our best judgement based on analysis of past cases. Although that number is now large enough that we can make some good assumptions, differences of interpretation will continue. Nonetheless, we may be on the cusp of reaching some agreement. Towards that end, I have contacted several Poison Centers and NAMA will be working with the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). -

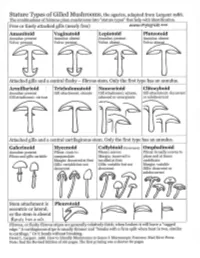

Agarics-Stature-Types.Pdf

Gilled Mushroom Genera of Chicago Region, by stature type and spore print color. Patrick Leacock – June 2016 Pale spores = white, buff, cream, pale green to Pinkish spores Brown spores = orange, Dark spores = dark olive, pale lilac, pale pink, yellow to pale = salmon, yellowish brown, rust purplish brown, orange pinkish brown brown, cinnamon, clay chocolate brown, Stature Type brown smoky, black Amanitoid Amanita [Agaricus] Vaginatoid Amanita Volvariella, [Agaricus, Coprinus+] Volvopluteus Lepiotoid Amanita, Lepiota+, Limacella Agaricus, Coprinus+ Pluteotoid [Amanita, Lepiota+] Limacella Pluteus, Bolbitius [Agaricus], Coprinus+ [Volvariella] Armillarioid [Amanita], Armillaria, Hygrophorus, Limacella, Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Coprinus+, Hypholoma, Neolentinus, Pleurotus, Tricholoma Cyclocybe, Gymnopilus Lacrymaria, Stropharia Hebeloma, Hemipholiota, Hemistropharia, Inocybe, Pholiota Tricholomatoid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Laccaria, Lactarius, Entoloma Cortinarius, Hebeloma, Lyophyllum, Megacollybia, Melanoleuca, Inocybe, Pholiota Russula, Tricholoma, Tricholomopsis Naucorioid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Hypsizygus, Laccaria, Entoloma Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Hypholoma Lactarius, Rhodocollybia, Rugosomyces, Hebeloma, Gymnopilus, Russula, Tricholoma Pholiota, Simocybe Clitocyboid Ampulloclitocybe, Armillaria, Cantharellus, Clitopilus Paxillus, [Pholiota], Clitocybe, Hygrophoropsis, Hygrophorus, Phylloporus, Tapinella Laccaria, Lactarius, Lactifluus, Lentinus, Leucopaxillus, Lyophyllum, Omphalotus, Panus, Russula Galerinoid Galerina, Pholiotina, Coprinus+, -

Toxicological and Pharmacological Profile of Amanita Muscaria (L.) Lam

Pharmacia 67(4): 317–323 DOI 10.3897/pharmacia.67.e56112 Review Article Toxicological and pharmacological profile of Amanita muscaria (L.) Lam. – a new rising opportunity for biomedicine Maria Voynova1, Aleksandar Shkondrov2, Magdalena Kondeva-Burdina1, Ilina Krasteva2 1 Laboratory of Drug metabolism and drug toxicity, Department “Pharmacology, Pharmacotherapy and Toxicology”, Faculty of Pharmacy, Medical University of Sofia, Bulgaria 2 Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Medical University of Sofia, Bulgaria Corresponding author: Magdalena Kondeva-Burdina ([email protected]) Received 2 July 2020 ♦ Accepted 19 August 2020 ♦ Published 26 November 2020 Citation: Voynova M, Shkondrov A, Kondeva-Burdina M, Krasteva I (2020) Toxicological and pharmacological profile of Amanita muscaria (L.) Lam. – a new rising opportunity for biomedicine. Pharmacia 67(4): 317–323. https://doi.org/10.3897/pharmacia.67. e56112 Abstract Amanita muscaria, commonly known as fly agaric, is a basidiomycete. Its main psychoactive constituents are ibotenic acid and mus- cimol, both involved in ‘pantherina-muscaria’ poisoning syndrome. The rising pharmacological and toxicological interest based on lots of contradictive opinions concerning the use of Amanita muscaria extracts’ neuroprotective role against some neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, its potent role in the treatment of cerebral ischaemia and other socially significant health conditions gave the basis for this review. Facts about Amanita muscaria’s morphology, chemical content, toxicological and pharmacological characteristics and usage from ancient times to present-day’s opportunities in modern medicine are presented. Keywords Amanita muscaria, muscimol, ibotenic acid Introduction rica, the genus had an ancestral origin in the Siberian-Be- ringian region in the Tertiary period (Geml et al. -

Amanita Muscaria (Fly Agaric)

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2018; 48: 85–91 | doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2018.119 PAPER Amanita muscaria (fly agaric): from a shamanistic hallucinogen to the search for acetylcholine HistoryMR Lee1, E Dukan2, I Milne3 & Humanities The mushroom Amanita muscaria (fly agaric) is widely distributed Correspondence to: throughout continental Europe and the UK. Its common name suggests MR Lee Abstract that it had been used to kill flies, until superseded by arsenic. The bioactive 112 Polwarth Terrace compounds occurring in the mushroom remained a mystery for long Merchiston periods of time, but eventually four hallucinogens were isolated from the Edinburgh EH11 1NN fungus: muscarine, muscimol, muscazone and ibotenic acid. UK The shamans of Eastern Siberia used the mushroom as an inebriant and a hallucinogen. In 1912, Henry Dale suggested that muscarine (or a closely related substance) was the transmitter at the parasympathetic nerve endings, where it would produce lacrimation, salivation, sweating, bronchoconstriction and increased intestinal motility. He and Otto Loewi eventually isolated the transmitter and showed that it was not muscarine but acetylcholine. The receptor is now known variously as cholinergic or muscarinic. From this basic knowledge, drugs such as pilocarpine (cholinergic) and ipratropium (anticholinergic) have been shown to be of value in glaucoma and diseases of the lungs, respectively. Keywords acetylcholine, atropine, choline, Dale, hyoscine, ipratropium, Loewi, muscarine, pilocarpine, physostigmine Declaration of interests No conflicts of interest declared Introduction recorded by the Swedish-American ethnologist Waldemar Jochelson, who lived with the tribes in the early part of the Amanita muscaria is probably the most easily recognised 20th century. His version of the tale reads as follows: mushroom in the British Isles with its scarlet cap spotted 1 with conical white fl eecy scales. -

Forest Fungi in Ireland

FOREST FUNGI IN IRELAND PAUL DOWDING and LOUIS SMITH COFORD, National Council for Forest Research and Development Arena House Arena Road Sandyford Dublin 18 Ireland Tel: + 353 1 2130725 Fax: + 353 1 2130611 © COFORD 2008 First published in 2008 by COFORD, National Council for Forest Research and Development, Dublin, Ireland. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from COFORD. All photographs and illustrations are the copyright of the authors unless otherwise indicated. ISBN 1 902696 62 X Title: Forest fungi in Ireland. Authors: Paul Dowding and Louis Smith Citation: Dowding, P. and Smith, L. 2008. Forest fungi in Ireland. COFORD, Dublin. The views and opinions expressed in this publication belong to the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of COFORD. i CONTENTS Foreword..................................................................................................................v Réamhfhocal...........................................................................................................vi Preface ....................................................................................................................vii Réamhrá................................................................................................................viii Acknowledgements...............................................................................................ix -

The Ectomycorrhizal Fungus Amanita Phalloides Was Introduced and Is

Molecular Ecology (2009) doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.04030.x TheBlackwell Publishing Ltd ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America ANNE PRINGLE,* RACHEL I. ADAMS,† HUGH B. CROSS* and THOMAS D. BRUNS‡ *Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Biological Laboratories, 16 Divinity Avenue, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA, †Department of Biological Sciences, Gilbert Hall, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305-5020, USA, ‡Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, 111 Koshland Hall, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA Abstract The deadly poisonous Amanita phalloides is common along the west coast of North America. Death cap mushrooms are especially abundant in habitats around the San Francisco Bay, California, but the species grows as far south as Los Angeles County and north to Vancouver Island, Canada. At different times, various authors have considered the species as either native or introduced, and the question of whether A. phalloides is an invasive species remains unanswered. We developed four novel loci and used these in combination with the EF1α and IGS loci to explore the phylogeography of the species. The data provide strong evidence for a European origin of North American populations. Genetic diversity is generally greater in European vs. North American populations, suggestive of a genetic bottleneck; polymorphic sites of at least two loci are only polymorphic within Europe although the number of individuals sampled from Europe was half the number sampled from North America. Endemic alleles are not a feature of North American populations, although alleles unique to different parts of Europe were common and were discovered in Scandinavian, mainland French, and Corsican individuals. -

Amanita Muscaria: Ecology, Chemistry, Myths

Entry Amanita muscaria: Ecology, Chemistry, Myths Quentin Carboué * and Michel Lopez URD Agro-Biotechnologies Industrielles (ABI), CEBB, AgroParisTech, 51110 Pomacle, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Definition: Amanita muscaria is the most emblematic mushroom in the popular representation. It is an ectomycorrhizal fungus endemic to the cold ecosystems of the northern hemisphere. The basidiocarp contains isoxazoles compounds that have specific actions on the central nervous system, including hallucinations. For this reason, it is considered an important entheogenic mushroom in different cultures whose remnants are still visible in some modern-day European traditions. In Siberian civilizations, it has been consumed for religious and recreational purposes for millennia, as it was the only inebriant in this region. Keywords: Amanita muscaria; ibotenic acid; muscimol; muscarine; ethnomycology 1. Introduction Thanks to its peculiar red cap with white spots, Amanita muscaria (L.) Lam. is the most iconic mushroom in modern-day popular culture. In many languages, its vernacular names are fly agaric and fly amanita. Indeed, steeped in a bowl of milk, it was used to Citation: Carboué, Q.; Lopez, M. catch flies in houses for centuries in Europe due to its ability to attract and intoxicate flies. Amanita muscaria: Ecology, Chemistry, Although considered poisonous when ingested fresh, this mushroom has been consumed Myths. Encyclopedia 2021, 1, 905–914. as edible in many different places, such as Italy and Mexico [1]. Many traditional recipes https://doi.org/10.3390/ involving boiling the mushroom—the water containing most of the water-soluble toxic encyclopedia1030069 compounds is then discarded—are available. In Japan, the mushroom is dried, soaked in brine for 12 weeks, and rinsed in successive washings before being eaten [2]. -

615.9Barref.Pdf

INDEX Abortifacient, abortifacients bees, wasps, and ants ginkgo, 492 aconite, 737 epinephrine, 963 ginseng, 500 barbados nut, 829 blister beetles goldenseal blister beetles, 972 cantharidin, 974 berberine, 506 blue cohosh, 395 buckeye hawthorn, 512 camphor, 407, 408 ~-escin, 884 hypericum extract, 602-603 cantharides, 974 calamus inky cap and coprine toxicity cantharidin, 974 ~-asarone, 405 coprine, 295 colocynth, 443 camphor, 409-411 ethanol, 296 common oleander, 847, 850 cascara, 416-417 isoxazole-containing mushrooms dogbane, 849-850 catechols, 682 and pantherina syndrome, mistletoe, 794 castor bean 298-302 nutmeg, 67 ricin, 719, 721 jequirity bean and abrin, oduvan, 755 colchicine, 694-896, 698 730-731 pennyroyal, 563-565 clostridium perfringens, 115 jellyfish, 1088 pine thistle, 515 comfrey and other pyrrolizidine Jimsonweed and other belladonna rue, 579 containing plants alkaloids, 779, 781 slangkop, Burke's, red, Transvaal, pyrrolizidine alkaloids, 453 jin bu huan and 857 cyanogenic foods tetrahydropalmatine, 519 tansy, 614 amygdalin, 48 kaffir lily turpentine, 667 cyanogenic glycosides, 45 lycorine,711 yarrow, 624-625 prunasin, 48 kava, 528 yellow bird-of-paradise, 749 daffodils and other emetic bulbs Laetrile", 763 yellow oleander, 854 galanthamine, 704 lavender, 534 yew, 899 dogbane family and cardenolides licorice Abrin,729-731 common oleander, 849 glycyrrhetinic acid, 540 camphor yellow oleander, 855-856 limonene, 639 cinnamomin, 409 domoic acid, 214 rna huang ricin, 409, 723, 730 ephedra alkaloids, 547 ephedra alkaloids, 548 Absorption, xvii erythrosine, 29 ephedrine, 547, 549 aloe vera, 380 garlic mayapple amatoxin-containing mushrooms S-allyl cysteine, 473 podophyllotoxin, 789 amatoxin poisoning, 273-275, gastrointestinal viruses milk thistle 279 viral gastroenteritis, 205 silibinin, 555 aspartame, 24 ginger, 485 mistletoe, 793 Medical Toxicology ofNatural Substances, by Donald G.