Toxicological and Pharmacological Profile of Amanita Muscaria (L.) Lam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tetrodotoxin

Niharika Mandal et al. / Journal of Pharmacy Research 2012,5(7),3567-3570 Review Article Available online through ISSN: 0974-6943 http://jprsolutions.info Tetrodotoxin: An intriguing molecule Niharika Mandal*, Samanta Sekhar Khora, Kanagaraj Mohanapriya, and Soumya Jal School of Biosciences and Technology, VIT University, Vellore-632013 Tamil Nadu, India Received on:07-04-2012; Revised on: 12-05-2012; Accepted on:16-06-2012 ABSTRACT Tetrodotoxin (TTX) is one of the most potent neurotoxin of biological origin. It was first isolated from puffer fish and it has been discovered in various arrays of organism since then. Its origin is still unclear though some reports indicate towards microbial origin. TTX selectively blocks the sodium channel, inhibiting action potential thereby, leading to respiratory paralysis. TTX toxicity is mainly caused due to consumption of puffer fish. No Known antidote for TTX exists. Treatment is symptomatic. The present review is therefore, an effort to give an idea about the distribution, origin, structure, pharmacol- ogy, toxicity, symptoms, treatment, resistance and application of TTX. Key words: Tetrodotoxin, Neurotoxin, Puffer fish. INTRODUCTION One of the most intriguing biotoxins isolated and described in the twentieth cantly more toxic than TTX. Palytoxin and maitotoxin have potencies nearly century is the neurotoxin, Tetrodotoxin (TTX, CAS Number [4368-28-9]). 100 times that of TTX and Saxitoxin, and all four toxins are unusual in being A neurotoxin is a toxin that acts specifically on neurons usually by interact- non-proteins. Interestingly, there is also some evidence for a bacterial bio- ing with membrane proteins and ion channels mostly resulting in paralysis. -

Mushrooms Russia and History

MUSHROOMS RUSSIA AND HISTORY BY VALENTINA PAVLOVNA WASSON AND R.GORDON WASSON VOLUME I PANTHEON BOOKS • NEW YORK COPYRIGHT © 1957 BY R. GORDON WASSON MANUFACTURED IN ITALY FOR THE AUTHORS AND PANTHEON BOOKS INC. 333, SIXTH AVENUE, NEW YORK 14, N. Y. www.NewAlexandria.org/ archive CONTENTS LIST OF PLATES VII LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE TEXT XIII PREFACE XVII VOLUME I I. MUSHROOMS AND THE RUSSIANS 3 II. MUSHROOMS AND THE ENGLISH 19 III. MUSHROOMS AND HISTORY 37 IV. MUSHROOMS FOR MURDERERS 47 V. THE RIDDLE OF THE TOAD AND OTHER SECRETS MUSHROOMIC 65 1. The Venomous Toad 66 2. Basques and Slovaks 77 3. The Cripple, the Toad, and the Devil's Bread 80 4. The 'Pogge Cluster 92 5. Puff balls, Filth, and Vermin 97 6. The Sponge Cluster 105 7. Punk, Fire, and Love 112 8. The Gourd Cluster 127 9. From 'Panggo' to 'Pupik' 138 10. Mucus, Mushrooms, and Love 145 11. The Secrets of the Truffle 166 12. 'Gripau' and 'Crib' 185 13. The Flies in the Amanita 190 v CONTENTS VOLUME II V. THE RIDDLE OF THE TOAD AND OTHER SECRETS MUSHROOMIC (CONTINUED) 14. Teo-Nandcatl: the Sacred Mushrooms of the Nahua 215 15. Teo-Nandcatl: the Mushroom Agape 287 16. The Divine Mushroom: Archeological Clues in the Valley of Mexico 322 17. 'Gama no Koshikake and 'Hegba Mboddo' 330 18. The Anatomy of Mycophobia 335 19. Mushrooms in Art 351 20. Unscientific Nomenclature 364 Vale 374 BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTES AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 381 APPENDIX I: Mushrooms in Tolstoy's 'Anna Karenina 391 APPENDIX II: Aksakov's 'Remarks and Observations of a Mushroom Hunter' 394 APPENDIX III: Leuba's 'Hymn to the Morel' 400 APPENDIX IV: Hallucinogenic Mushrooms: Early Mexican Sources 404 INDEX OF FUNGAL METAPHORS AND SEMANTIC ASSOCIATIONS 411 INDEX OF MUSHROOM NAMES 414 INDEX OF PERSONS AND PLACES 421 VI LIST OF PLATES VOLUME I JEAN-HENRI FABRE. -

Amnestic Concentrations of Sevoflurane Inhibit Synaptic

Anesthesiology 2008; 108:447–56 Copyright © 2008, the American Society of Anesthesiologists, Inc. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. Amnestic Concentrations of Sevoflurane Inhibit Synaptic Plasticity of Hippocampal CA1 Neurons through ␥-Aminobutyric Acid–mediated Mechanisms Junko Ishizeki, M.D.,* Koichi Nishikawa, M.D., Ph.D.,† Kazuhiro Kubo, M.D.,‡ Shigeru Saito, M.D., Ph.D.,§ Fumio Goto, M.D., Ph.D. Background: The cellular mechanisms of anesthetic-induced for surgical procedures do not have recollection of ac- amnesia are still poorly understood. The current study exam- tually being awake despite being awake and cooperative ined sevoflurane at various concentrations in the CA1 region of during the procedure.1 Galinkin et al.2 compared sub- rat hippocampal slices for effects on excitatory synaptic trans- Downloaded from http://pubs.asahq.org/anesthesiology/article-pdf/108/3/447/366512/0000542-200803000-00017.pdf by guest on 29 September 2021 mission and on long-term potentiation (LTP), as a possible jective, psychomotor, cognitive, and analgesic effects of mechanism contributing to anesthetic-induced loss of recall. sevoflurane (0.3% and 0.6%) with those of nitrous oxide Methods: Population spikes and field excitatory postsynaptic at equal minimum alveolar concentrations (MACs) in potentials were recorded using extracellular electrodes after healthy volunteers. They found that sevoflurane pro- electrical stimulation of Schaffer-collateral-commissural fiber inputs. Paired pulse facilitation was used as a measure of pre- duced a greater degree of amnesia and psychomotor synaptic effects of the anesthetic. LTP was induced using tetanic impairment than did an equal MAC of nitrous oxide but stimulation (100 Hz, 1 s). Sevoflurane at concentrations from had no analgesic actions. -

Picrotoxin-Like Channel Blockers of GABAA Receptors

COMMENTARY Picrotoxin-like channel blockers of GABAA receptors Richard W. Olsen* Department of Molecular and Medical Pharmacology, Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1735 icrotoxin (PTX) is the prototypic vous system. Instead of an acetylcholine antagonist of GABAA receptors (ACh) target, the cage convulsants are (GABARs), the primary media- noncompetitive GABAR antagonists act- tors of inhibitory neurotransmis- ing at the PTX site: they inhibit GABAR Psion (rapid and tonic) in the nervous currents and synapses in mammalian neu- system. Picrotoxinin (Fig. 1A), the active rons and inhibit [3H]dihydropicrotoxinin ingredient in this plant convulsant, struc- binding to GABAR sites in brain mem- turally does not resemble GABA, a sim- branes (7, 9). A potent example, t-butyl ple, small amino acid, but it is a polycylic bicyclophosphorothionate, is a major re- compound with no nitrogen atom. The search tool used to assay GABARs by compound somehow prevents ion flow radio-ligand binding (10). through the chloride channel activated by This drug target appears to be the site GABA in the GABAR, a member of the of action of the experimental convulsant cys-loop, ligand-gated ion channel super- pentylenetetrazol (1, 4) and numerous family. Unlike the competitive GABAR polychlorinated hydrocarbon insecticides, antagonist bicuculline, PTX is clearly a including dieldrin, lindane, and fipronil, noncompetitive antagonist (NCA), acting compounds that have been applied in not at the GABA recognition site but per- huge amounts to the environment with haps within the ion channel. Thus PTX major agricultural economic impact (2). ͞ appears to be an excellent example of al- Some of the other potent toxicants insec- losteric modulation, which is extremely ticides were also radiolabeled and used to important in protein function in general characterize receptor action, allowing and especially for GABAR (1). -

Zetekitoxin AB

Zetekitoxin AB Kate Wilkin Laura Graham Background of Zetekitoxin AB Potent water-soluble guanidinium toxin extracted from the skin of the Panamanian golden frog, Atelopus zeteki. Identified by Harry S. Mosher and colleagues at Stanford University, 1969. Originally named 1,2- atelopidtoxin. Progression 1975 – found chiriquitoxin in a Costa Rican Atelopus frog. 1977 – Mosher isolated 2 components of 1,2-atelopidtoxin. AB major component, more toxic C minor component, less toxic 1986 – purified from skin extracts by Daly and Kim. 1990 – the major component was renamed after the frog species zeteki. Classification Structural Identification Structural Identification - IR -1 Cm Functional Groups 1268 OSO3H 1700 Carbamate 1051 – 1022 C – N Structural Identification – MS Structural Identification – 13C Carbon Number Ppm Assignment 2 ~ 159 C = NH 4 ~ 85 Quaternary Carbon 5 ~ 59 Tertiary Carbon 6 ~ 54 Tertiary Carbon 8 ~ 158 C = NH Structural Identification – 13C Carbon Number Ppm Assignment 10 55 / 43 C H2 - more subst. on ZTX 11 89 / 33 Ring and OSO3H on ZTX 12 ~ 98 Carbon attached to 2 OH groups 19 / 13 70 / 64 ZTX: C – N STX: C – C 20 / 14 ~ 157 Carbamate Structural Identification – 13C Carbon Number Ppm Assignment 13 156 Amide 14 34 CH2 15 54 C – N 16 47 Tertiary Carbon 17 69 C – O – N 18 62 C – OH Structural Identification - 1H Synthesis Synthesis O. Iwamoto and Dr. K. Nagasawa Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology. October 10th, 2007 “Further work to synthesize natural STXs and various derivatives is in progress with the aim of developing isoform-selective sodium-channel inhibitors” Therapeutic Applications Possible anesthetic, but has poor therapeutic index. -

Bur¯Aq Depicted As Amanita Muscaria in a 15Th Century Timurid-Illuminated Manuscript?

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Journal of Psychedelic Studies 3(2), pp. 133–141 (2019) DOI: 10.1556/2054.2019.023 First published online September 24, 2019 Bur¯aq depicted as Amanita muscaria in a 15th century Timurid-illuminated manuscript? ALAN PIPER* Independent Scholar, Newham, London, UK (Received: May 8, 2019; accepted: August 2, 2019) A series of illustrations in a 15th century Timurid manuscript record the mi’raj, the ascent through the seven heavens by Mohammed, the Prophet of Islam. Several of the illustrations depict Bur¯aq, the fabulous creature by means of which Mohammed achieves his ascent, with distinctive features of the Amanita muscaria mushroom. A. muscaria or “fly agaric” is a psychoactive mushroom used by Siberian shamans to enter the spirit world for the purposes of conversing with spirits or diagnosing and curing disease. Using an interdisciplinary approach, the author explores the routes by which Bur¯aq could have come to be depicted in this manuscript with the characteristics of a psychoactive fungus, when any suggestion that the Prophet might have had recourse to a drug to accomplish his spirit journey would be anathema to orthodox Islam. There is no suggestion that Mohammad’s night journey (isra) or ascent (mi’raj) was accomplished under the influence of a psychoactive mushroom or plant. Keywords: Mi’raj, Timurid, Central Asia, shamanism, Siberia, Amanita muscaria CULTURAL CONTEXT Bur¯aq depicted as Amanita muscaria in the mi’raj manscript The mi’raj manuscript In the Muslim tradition, the mi’raj was preceded by the isra or “Night Journey” during which Mohammed traveled An illustrated manuscript depicting, in a series of miniatures, overnight from Mecca to Jerusalem by means of a fabulous thesuccessivestagesofthemi’raj, the miraculous ascent of beast called Bur¯aq. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2013/0034530 A1 Fantz (43) Pub

US 2013 0034530A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2013/0034530 A1 Fantz (43) Pub. Date: Feb. 7, 2013 (54) DIETARY SUPPLEMENT COGNITIVE (52) U.S. Cl. ....................................... 424/94.2; 424/643 SUPPORT SYSTEM (57) ABSTRACT (75) Inventor: David Robert Fantz, Denver, CO (US) The present invention relates to a nutritional Supplement composition, comprising a therapeutically effective amounts of Vitamin C, Vitamin D3. Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vita (73) Assignee: David R. Fantz, Denver, CO (US) min B6, Folic acid, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic acid, Calcium, Magnesium, Zinc, Chromium, Sugar, Protein, Acetyl-L-Car (21) Appl. No.: 13/456,287 nitine, Dimethylaminoethanol complex, Phosphatidylserine complex, L-Glutamine, N-Acetyl-L-Tyrosine, L-Phenylala nine, Taurine, Methionine, Valine, Isoleucine, 5 Hydrox (22) Filed: Apr. 26, 2012 ytryptophan, L-Taurine, N-Acetyl-Tyrosine, N-Acetyl-L- Cysteine, Alpha Lipoic Acid, Alpha Related U.S. Application Data Glycerylphosphoricholine complex, Bacopa Monnieri extract, Gingko Biloba extract, Passion flower, Lemon Balm, (60) Provisional application No. 61/480.372, filed on Apr. Gotu Kola, Ashwagandha, Choline Bitartrate complex, Panax 29, 2011. Ginseng extract, Turmeric, Organic freeze dried fruit juice blends (concord grape, red raspberry, pineapple, cranberry, Publication Classification acai, pomegranate, acerola cherry, bilberry, lingonberry, black currant, aronia, Sour cherry, black raspberry), Organic (51) Int. Cl. freeze dried greens blends (barley grass, broccoli, beet, car A6 IK33/30 (2006.01) rot, alfalfa, oat), and Protein digestive enzyme blends (Pro A6IP3/02 (2006.01) tease 4.5, peptidase, bromelain, protease 6.0, protease 3.0, L A6IP 25/00 (2006.01) planatrum, B bifidum) in a mixture to provide optimal cog A6 IK38/54 (2006.01) nitive function. -

Field Guide to Common Macrofungi in Eastern Forests and Their Ecosystem Functions

United States Department of Field Guide to Agriculture Common Macrofungi Forest Service in Eastern Forests Northern Research Station and Their Ecosystem General Technical Report NRS-79 Functions Michael E. Ostry Neil A. Anderson Joseph G. O’Brien Cover Photos Front: Morel, Morchella esculenta. Photo by Neil A. Anderson, University of Minnesota. Back: Bear’s Head Tooth, Hericium coralloides. Photo by Michael E. Ostry, U.S. Forest Service. The Authors MICHAEL E. OSTRY, research plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station, St. Paul, MN NEIL A. ANDERSON, professor emeritus, University of Minnesota, Department of Plant Pathology, St. Paul, MN JOSEPH G. O’BRIEN, plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, St. Paul, MN Manuscript received for publication 23 April 2010 Published by: For additional copies: U.S. FOREST SERVICE U.S. Forest Service 11 CAMPUS BLVD SUITE 200 Publications Distribution NEWTOWN SQUARE PA 19073 359 Main Road Delaware, OH 43015-8640 April 2011 Fax: (740)368-0152 Visit our homepage at: http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/ CONTENTS Introduction: About this Guide 1 Mushroom Basics 2 Aspen-Birch Ecosystem Mycorrhizal On the ground associated with tree roots Fly Agaric Amanita muscaria 8 Destroying Angel Amanita virosa, A. verna, A. bisporigera 9 The Omnipresent Laccaria Laccaria bicolor 10 Aspen Bolete Leccinum aurantiacum, L. insigne 11 Birch Bolete Leccinum scabrum 12 Saprophytic Litter and Wood Decay On wood Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus populinus (P. ostreatus) 13 Artist’s Conk Ganoderma applanatum -

GABA Receptors

D Reviews • BIOTREND Reviews • BIOTREND Reviews • BIOTREND Reviews • BIOTREND Reviews Review No.7 / 1-2011 GABA receptors Wolfgang Froestl , CNS & Chemistry Expert, AC Immune SA, PSE Building B - EPFL, CH-1015 Lausanne, Phone: +41 21 693 91 43, FAX: +41 21 693 91 20, E-mail: [email protected] GABA Activation of the GABA A receptor leads to an influx of chloride GABA ( -aminobutyric acid; Figure 1) is the most important and ions and to a hyperpolarization of the membrane. 16 subunits with γ most abundant inhibitory neurotransmitter in the mammalian molecular weights between 50 and 65 kD have been identified brain 1,2 , where it was first discovered in 1950 3-5 . It is a small achiral so far, 6 subunits, 3 subunits, 3 subunits, and the , , α β γ δ ε θ molecule with molecular weight of 103 g/mol and high water solu - and subunits 8,9 . π bility. At 25°C one gram of water can dissolve 1.3 grams of GABA. 2 Such a hydrophilic molecule (log P = -2.13, PSA = 63.3 Å ) cannot In the meantime all GABA A receptor binding sites have been eluci - cross the blood brain barrier. It is produced in the brain by decarb- dated in great detail. The GABA site is located at the interface oxylation of L-glutamic acid by the enzyme glutamic acid decarb- between and subunits. Benzodiazepines interact with subunit α β oxylase (GAD, EC 4.1.1.15). It is a neutral amino acid with pK = combinations ( ) ( ) , which is the most abundant combi - 1 α1 2 β2 2 γ2 4.23 and pK = 10.43. -

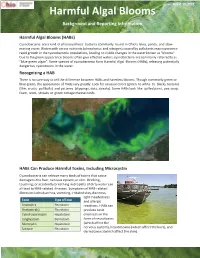

Harmful Algal Blooms Background and Reporting Information

Rev 8-12-2019 Harmful Algal Blooms Background and Reporting Information Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) Cyanobacteria are a kind of photosynthetic bacteria commonly found in Ohio’s lakes, ponds, and slow- moving rivers. Waters with excess nutrients (phosphorus and nitrogen) caused by pollutants may experience rapid growth in the cyanobacteria populations, leading to visible changes in the water known as “blooms”. Due to the green appearance blooms often give effected waters, cyanobacteria are commonly referred to as “blue-green algae”. Some species of cyanobacteria form Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs), releasing potentially dangerous cyanotoxins in the water. Recognizing a HAB There is no sure way to tell the difference between HABs and harmless blooms. Though commonly green or blue-green, the appearance of HABs vary greatly. Look for unusual colors (green to white to black), textures (film, crusts, puffballs) and patterns (clippings, dots, streaks). Some HABs look like spilled paint, pea soup, foam, wool, streaks or green cottage cheese curds. HABs Can Produce Harmful Toxins, Including Microcystin Cyanobacteria can release many kinds of toxins that cause damage to the liver, nervous system, or skin. Drinking, touching, or accidently breathing in droplets of dirty water can all lead to HAB-related illnesses. Symptoms of HAB-related illness includes diarrhea, vomiting, irritated skin, dizziness, light-headedness Toxin Type of Toxin and allergic Anatoxin-a Neurotoxin reactions. HABs can Anatoxin-a(s) Neurotoxin produce toxic Cylindrospermopsin Hepatotoxin chemicals in the Lyngbyatoxin Dermatoxin form of neurotoxins Microcystin Hepatotoxin (which affect the Saxitoxin Neurotoxin nervous system), hepatotoxins (which affect the liver), and dermatoxins (which affect the skin). -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110449 A1 Lorber Et Al

US 200601 10449A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110449 A1 LOrber et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 25, 2006 (54) PHARMACEUTICAL COMPOSITION Publication Classification (76) Inventors: Richard R. Lorber, Scotch Plains, NJ (US); Heribert W. Staudinger, Union, (51) Int. Cl. NJ (US); Robert E. Ward, Summit, NJ A6II 3/473 (2006.01) (US) A6II 3L/24 (2006.01) Correspondence Address: A6IR 9/20 (2006.01) SCHERING-PLOUGH CORPORATION (52) U.S. Cl. ........................... 424/464; 514/290: 514/540 PATENT DEPARTMENT (K-6-1, 1990) 2000 GALLOPNG HILL ROAD KENILWORTH, NJ 07033-0530 (US) (57) ABSTRACT (21) Appl. No.: 11/257,348 (22) Filed: Oct. 24, 2005 The present invention relates to formulations useful for Related U.S. Application Data treating respiratory disorders associated with the production of mucus glycoprotein, skin disorders, and allergic conjunc (60) Provisional application No. 60/622,507, filed on Oct. tivitis while substantially reducing adverse effects associ 27, 2004. Provisional application No. 60/621,783, ated with the administration of non-selective anti-cholin filed on Oct. 25, 2004. ergic agents and methods of use thereof. US 2006/01 10449 A1 May 25, 2006 PHARMACEUTICAL COMPOSITION example, Weinstein and Weinstein (U.S. Pat. No. 6,086,914) describe methods of treating allergic rhinitis using an anti CROSS REFERENCE TO RELATED cholinergic agent with a limited capacity to pass across lipid APPLICATION membranes, such as the blood-brain barrier, in combination with an antihistamine that is limited in both sedating and 0001. This application claims benefit of priority to U.S. -

Optimal Foods

Optimal Foods 1. Almonds: high in monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, with 20% of calories coming from protein and dietary fiber. Nutrients include potassium, magnesium, calcium, iron, zinc, vitamin E and an antioxidant flavonoid called amygdlin also known as laetrile. 2. Barley: Like oat bran it is high in beta-glucan fiber which helps to lower cholesterol. Nutrients include copper, magnesium, phosphorous and niacin. 3. Berries : The darker the berry the higher in anti-oxidants. Nutritionally they are an excellent source of flavonoids, especially anthocyanidins, vitamin C and both soluble and insoluble fiber. 4. Brussels Sprouts : Similar to broccoli, and a member of the cabbage family, it contains cancer fighting glucosinolates. Nutritionally it is an excellent source of vitamin C and K, the B vitamins, beta-carotene, potassium and dietary fiber. 5. Carrots: It contains the highest source of proviatamin A carotenes as well as vitamin K, biotin, vitamin C, B6, potassium, thiamine and fiber. 6. Dark Chocolate: It is rich in the flavonoids, similar to those found in berries and apples, that are more easily absorbed than in other foods. It also provides an amino acid called arginine that helps blood vessels to dilate hence regulating blood flow and helping to lower blood pressure. Choose high-quality semisweet dark chocolate with the highest cocoa content that appeals to your taste buds. 7. Dark leafy greens : Kale, arugula, spinach, mustard greens, chard, collards, etc: low calorie, anti-oxidant dense food with carotenes, vitamin C, folic acid, manganese, copper, vitamin E, copper, vitamin B6, potassium, calcium, iron and dietary fiber. Kale is a particularly excellent bioavailable source of calcium while spinach is not.