Janus and Minerva

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Journey in Pictures Through Roman Religion

A Journey in Pictures through Roman Religion By Ursula Kampmann, © MoneyMuseum What is god? As far as the Romans are concerned we think we know that all too well from our unloved Latin lessons: Jupiter, Juno, Minerva, the Roman Triad as well as the usual gods of the ancient world, the same as the Greek gods in name and effect. In fact, however, the roots of Roman religion lie much earlier, much deeper, in dark, prehistoric times ... 1 von 20 www.sunflower.ch How is god experienced? – In the way nature works A bust of the goddess Flora (= flowering), behind it blossom. A denarius of the Roman mint master C. Clodius Vestalis, 41 BC Roman religion emerged from the magical world of the simple farmer, who was speechless when faced with the miracles of nature. Who gave the seemingly withered trees new blossom after the winter? Which power made the grain of corn in the earth grow up to produce new grain every year? Which god prevented the black rust and ensured that the weather was fine just in time for the harvest? Who guaranteed safe storage? And which power was responsible for making it possible to divide up the corn so that it sufficed until the following year? Each individual procedure in a farmer's life was broken down into many small constituent parts whose success was influenced by a divine power. This divine power had to be invoked by a magic ritual in order to grant its help for the action. Thus as late as the imperial period, i.e. -

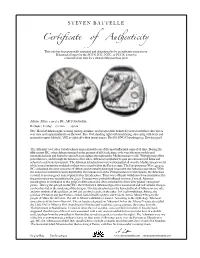

Ceificate of Auenticity

S T E V E N B A T T E L L E Ce!ificate of Au"enticity This coin has been personally inspected and determined to be an authentic ancient coin . If deemed a forgery by the ACCS, IGC, NGC, or PCGS, it may be returned at any time for a refund of the purchase price. Athens, Attica, 449-404 BC, AR Tetradrachm B076961 / U02697 17.1 Gm 25 mm Obv: Head of Athena right, wearing earring, necklace, and crested Attic helmet decorated with three olive leaves over visor and a spiral palmette on the bowl. Rev: Owl standing right with head facing, olive sprig with berry and crescent in upper left field, AOE to right; all within incuse square. Kroll 8; SNG Copenhagen 31; Dewing 1591-8 The Athenian “owl” silver tetradrachm is unquestionably one of the most influential coins of all time. During the fifth century BC, when Athens emerged as the greatest of all Greek cities, owls were the most widely used international coin and helped to spread Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean world. With the help of her powerful navy, and through the taxation of her allies, Athens accomplished to gain pre-eminance in Hellas and achieved a celebrated prosperity. The Athenian tetradrachms were well-accepted all over the Mediterranean world, while several imitations modeled on them were issued within the Persian state. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) exhausted the silver resources of Athens and eventually destroyed irreparably the Athenian supremacy. With the mines lost and their treasury depleted by the ruinous cost of the Pelloponesian war with Sparta, the Athenians resorted to an emergency issue of plated silver tetradrachms. -

Ovid, Fasti 1.63-294 (Translated By, and Adapted Notes From, A

Ovid, Fasti 1.63-294 (translated by, and adapted notes from, A. S. Kline) [Latin text; 8 CE] Book I: January 1: Kalends See how Janus1 appears first in my song To announce a happy year for you, Germanicus.2 Two-headed Janus, source of the silently gliding year, The only god who is able to see behind him, Be favourable to the leaders, whose labours win Peace for the fertile earth, peace for the seas: Be favourable to the senate and Roman people, And with a nod unbar the shining temples. A prosperous day dawns: favour our thoughts and speech! Let auspicious words be said on this auspicious day. Let our ears be free of lawsuits then, and banish Mad disputes now: you, malicious tongues, cease wagging! See how the air shines with fragrant fire, And Cilician3 grains crackle on lit hearths! The flame beats brightly on the temple’s gold, And spreads a flickering light on the shrine’s roof. Spotless garments make their way to Tarpeian Heights,4 And the crowd wear the colours of the festival: Now the new rods and axes lead, new purple glows, And the distinctive ivory chair feels fresh weight. Heifers that grazed the grass on Faliscan plains,5 Unbroken to the yoke, bow their necks to the axe. When Jupiter watches the whole world from his hill, Everything that he sees belongs to Rome. Hail, day of joy, and return forever, happier still, Worthy to be cherished by a race that rules the world. But two-formed Janus what god shall I say you are, Since Greece has no divinity to compare with you? Tell me the reason, too, why you alone of all the gods Look both at what’s behind you and what’s in front. -

Paper Information: Title: the Realm of Janus: Doorways in the Roman

Paper Information: Title: The Realm of Janus: Doorways in the Roman World Author: Ardle Mac Mahon Pages: 58–73 DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/TRAC2002_58_73 Publication Date: 03 April 2003 Volume Information: Carr, G., Swift, E., and Weekes, J. (eds.) (2003) TRAC 2002: Proceedings of the Twelfth Annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference, Canterbury 2002. Oxford: Oxbow Books. Copyright and Hardcopy Editions: The following paper was originally published in print format by Oxbow Books for TRAC. Hard copy editions of this volume may still be available, and can be purchased direct from Oxbow at http://www.oxbowbooks.com. TRAC has now made this paper available as Open Access through an agreement with the publisher. Copyright remains with TRAC and the individual author(s), and all use or quotation of this paper and/or its contents must be acknowledged. This paper was released in digital Open Access format in April 2013. The Realm of Janus: Doorways in the Roman World Ardle Mac Mahon For the Romans, the doorways into their dwellings had tremendous symbolic and spiritual significance and this aspect was enshrined around the uniquely Latin god Janus. The importance of principal entrance doorways was made obvious by the architectural embell ishments used to decorate doors and door surrounds that helped to create an atmosphere of sacred and ritual eminence. The threshold was not only an area of physical transition but also of symbolic change intimately connected to the lives of the inhabitants of the dwelling. This paper will explore the meaning of the architectural symbolism of the portal and the role of doorways in ritual within the Roman empire by an examination of the architectural remains and the literary sources. -

Triangular Numbers in Henry Peacham's Minerva Britanna

Brief Chronicles IV (2012-13) 89 Triangular Numbers in Henry Peacham’s Minerva Britanna: A Study in Jacobean Literary Form Roger Stritmatter his article investigates the presence of a concealed and previously undetected numerical symbolism in a Stuart-era emblem book, Henry TPeacham’s Minerva Britanna (1611). Although alien to modern conceptions of art, emblem books constitute one of the most widely published and popular genres in early modern book production. Drawing from an eclectic tradition of literary, religious, and iconological traditions, the emblem book combined words and images into complex patterns of signification, often of a markedly didactic character. Popular in all the European vernaculars, it appealed to a wide range of Renaissance readers, from the nearly illiterate (by virtue of its illustrated nature) to the most erudite (by virtue of its reputation for dazzling displays of intellectual and aesthetic virtuosity). By convention the emblem was divided into three parts: superscriptio, pictura, and subscriptio: the superscriptio was the short legend or motto that typically appeared at the top of the page; below it appeared the pictura – the emblem per se – followed by the subscriptio, a longer responsive analysis, usually written in verse, which completed the design. While emblem book scholars still debate the exact relationship between the three parts – and no doubt individual emblem writers themselves sometimes conceived of it in different ways, Deitrich Walter Jöns’ definition constitutes a useful and standard point -

Johnlydus-4-01-January – Final

JANUARY [63] 1. I have spoken sufficiently about the fact that the month of January was defined as the beginning of the priestly calendar by King Numa; in it, they would offer sacrifice to the [beings] above the moon, just as in February [they would offer sacrifice] to the [beings] below it. And so, I must speak about Janus—who he is and what idea of him the ancients had. Now then, Labeo says1 that he is called Janus Consivius, that is, "of the council / Senate" [boulaios]; Janus Cenulus and Cibullius, that is, "pertaining to feasting"—for the Romans called food cibus; Patricius, that is, "indigenous"; Clusivius, meaning "pertaining to journeys" [hodiaios]; Junonius, that is, "aerial"; Quirinus, meaning "champion / fighter in the front"; Patulcius and Clusius, that is, "of the door"; Curiatius, as "overseer of nobles"—for Curiatius and Horatius are names of [Roman] nobility. And some relate that he is double in form [64], at one time holding keys in his right hand like a door-keeper, at other times counting out 300 counters in his right hand and 65 in the other, just like [the number of days in] the year. From this,2 he is also [said to be] quadruple in form, from the four "turns" [i.e., the solstices and equinoxes]—and a statue of him of this type is said to be preserved even now in the Forum of Nerva.3 But Longinus vehemently tries to interpret him as Aeonarius, as being the father of Aeon, or that [he got his name because] the Greeks called the year4 enos, as Callimachus in the first book of the Aetia writes: Four-year-old [tetraenon] child of Damasus, Telestorides5.. -

Dream Goddess:Athena

Dream Goddess: Athena Goddess of Wisdom & War Women who embody the Athena archetype are not afraid of their power—in fact they thrive on it. They are achievement oriented, alpha “A- type” personalities. They tend to identify themselves with their work, projects, or creative endeavors, and thus are extremely driven. Contemporary Athena women in Western culture are natural leaders, who usually find themselves either working for themselves or climbing to the top of the corporate ladder. They don’t typically complain about the proverbial “glass ceiling” because they are too busy making strides, working hard, and focusing on the goal they are achieving than on how difficult it is to make it in a “man’s world.” Women ruled by Athena live in a world where they know if they work hard enough, they can create their own destiny. They can be competitive with men and women alike (anyone who stands in the way of her reaching the brass ring she is striving for). The cost of being overly “Athena” can be adrenal burn out, constantly feeling at war, and thus being criticized for being “ruthless” and a “bitch”. Being an extreme Athena archetype can be a lonely road since there’s only room at the top for one person— relationships can be opportunistic, conditional, thus not deep, long-lasting, and satisfying. 1 Athena women’s dreams are filled with wisdom and strategic guidance about how to get ahead in business and become more successful. If you’re not an Athena woman, you definitely want to be on her good side. -

The Statue of Janus Geminus and the Gates of War

The Hands of the Double God: The Statue of Janus Geminus and the Gates of War The bronze gates attached to the shrine of Janus Geminus in the Roman forum are well known, and many explanations have been proposed to explain the origin of the counter-intuitive tradition of closing the gates during peacetime and opening them during war. This project seeks to turn attention to another, less studied component of the cult: the bronze statue of Janus behind the gates. It is my intention to demonstrate that it was replaced at some point, almost certainly by Augustus. Ovid (Fasti 1.99) claims that Janus held a staff in his right hand and a key in his left. Pliny (Natural History 34.16.33; cf. Macrobius 1.9.10), on the other hand, claims that Janus was depicted with his fingers shaped so as to indicate the 365 days of the year. How exactly the statue’s fingers indicated the number 35 has been a matter of uncertainty; one recurrent explanation is that the statues fingers were contorted so as to suggest the letters of the Roman numerals for 365: the letters c, l, x, and v. In fact, no such grotesque explanation is necessary. The Romans possessed a tabulation system that used the fingers of both hands to count. The fullest account is preserved by the Venerable Bede in De Temporum Ratione. According to Bede, one would indicate the number 300 with the right hand; one would indicate 65 with the left hand; that this is what Pliny intends for us to understand has the position of Janus’ fingers is confirmed by John Lydus (1.4), who explicitly states that Janus indicated 300 with his right hand and 65 with his left hand. -

Ancient Rome

HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY Ancient Julius Caesar Rome Reader Caesar Augustus The Second Punic War Cleopatra THIS BOOK IS THE PROPERTY OF: STATE Book No. PROVINCE Enter information COUNTY in spaces to the left as PARISH instructed. SCHOOL DISTRICT OTHER CONDITION Year ISSUED TO Used ISSUED RETURNED PUPILS to whom this textbook is issued must not write on any page or mark any part of it in any way, consumable textbooks excepted. 1. Teachers should see that the pupil’s name is clearly written in ink in the spaces above in every book issued. 2. The following terms should be used in recording the condition of the book: New; Good; Fair; Poor; Bad. Ancient Rome Reader Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You are free: to Share—to copy, distribute, and transmit the work to Remix—to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution—You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation (www.coreknowledge.org) made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial—You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike—If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. -

The Agency of Prayers: the Legend of M

The Agency of Prayers: The Legend of M. Furius Camillus in Dionysius of Halicarnassus Beatrice Poletti N THIS PAPER, I examine the ‘curse’ that Camillus casts on his fellow citizens as they ban him from Rome on the accu- sations of mishandling the plunder from Veii and omitting I 1 to fulfill a vow to Apollo. Accounts of this episode (including Livy’s, Plutarch’s, and Appian’s) more or less explicitly recall, in their description of Camillus’ departure, the Homeric prece- dent of Achilles withdrawing from battle after his quarrel with Agamemnon, when he anticipates “longing” for him by the Achaean warriors. Dionysius of Halicarnassus appears to fol- low a different inspiration, in which literary topoi combine with prayer ritualism and popular magic. In his rendering, Camillus pleads to the gods for revenge and entreats them to inflict punishment on the Romans, so that they would be compelled to revoke their sentence. As I show, the terminology used in Dionysius’ reconstruction is reminiscent of formulas in defixi- 1 I.e., the affair of the praeda Veientana. Livy, followed by other sources, relates that before taking Veii Camillus had vowed a tenth of the plunder to Apollo. Because of his mismanagement, the vow could not be immediately fulfilled and, when the pontiffs proposed that the populace should discharge the religious obligation through their share of the plunder, Camillus faced general discontent and eventually a trial (Liv. 5.21.2, 5.23.8–11, 5.25.4–12, 5.32.8–9; cf. Plut. Cam. 7.5–8.2, 11.1–12.2; App. -

SUMMER 2016 HONORS LATIN III GRADE 11: Title: Roman Blood

SUMMER 2016 HONORS LATIN III GRADE 11: Title: Roman Blood: A Novel of Ancient Rome Author: Steven Saylor Publisher: St. Martin’s Minotaur Year: 2000 ISBN: 9780312972967 You will be creating a magazine based on this novel. Be creative. Everything about your magazine should be centered around the theme of the novel. Your magazine must contain the following: Cover Table of Contents One: Crossword puzzle OR Word search OR Cryptogram At least 6 (six) news articles which may consist of character interviews, background on the time period, slave/master relationship, Roman law, etc. It is not necessary to interview Saylor. One of the following: horoscopes (relevant to the novel), cartoons (relevant to the novel), recipes (relevant to the novel), want ads (relevant to the novel), general advertisements for products/services (relevant to the novel). There must be no “white/blank” space in the magazine. It must be laid out and must look like a magazine and not just pages stapled together. This must be typed and neatly done. Due date is first day of school in August. PLEASE NOTE: You will need $25 for membership in the Classical organizations and for participation in three national exams. Due date: September 1, 2016. Thank you. SUMMER 2016 LATIN II GRADE 10: Amsco Workbook: Work on the review sections after verbs, nouns and adjectives. Complete all mastery exercises on pp. 36-39, 59-61, 64-66, 92-95, 102-104. Please be sure to study all relevant vocab in these mastery exercises. Due date is first day of school in August. PLEASE NOTE: You will need $25 for membership in the Classical organizations and for participation in three national exams. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th.