Deconstructing Toxic Masculinity in Michael Flatley's Lord

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rokdim-Nirkoda” #99 Is Before You in the Customary Printed Format

Dear Readers, “Rokdim-Nirkoda” #99 is before you in the customary printed format. We are making great strides in our efforts to transition to digital media while simultaneously working to obtain the funding מגזין לריקודי עם ומחול .to continue publishing printed issues With all due respect to the internet age – there is still a cultural and historical value to publishing a printed edition and having the presence of a printed publication in libraries and on your shelves. עמותת ארגון המדריכים Yaron Meishar We are grateful to those individuals who have donated funds to enable והיוצרים לריקודי עם financial the encourage We editions. printed recent of publication the support of our readers to help ensure the printing of future issues. This summer there will be two major dance festivals taking place Magazine No. 99 | July 2018 | 30 NIS in Israel: the Karmiel Festival and the Ashdod Festival. For both, we wish and hope for their great success, cooperation and mutual YOAV ASHRIEL: Rebellious, Innovative, enrichment. Breaks New Ground Thank you Avi Levy and the Ashdod Festival for your cooperation 44 David Ben-Asher and your use of “Rokdim-Nirkoda” as a platform to reach you – the Translation: readers. Thank you very much! Ruth Schoenberg and Shani Karni Aduculesi Ruth Goodman Israeli folk dances are danced all over the world; it is important for us to know and read about what is happening in this field in every The Light Within DanCE place and country and we are inviting you, the readers and instructors, 39 The “Hora Or” Group to submit articles about the background, past and present, of Israeli folk Eti Arieli dance as it is reflected in the city and country in which you are active. -

1St Annual Dreams Come True Feis Hosted by Central Florida Irish Dance Sunday August 8Th, 2021

1st Annual Dreams Come True Feis Hosted by Central Florida Irish Dance Sunday August 8th, 2021 Musician – Sean Warren, Florida. Adjudicator’s – Maura McGowan ADCRG, Belfast Arlene McLaughlin Allen ADCRG - Scotland Hosted by - Sarah Costello TCRG and Central Florida Irish Dance Embassy Suites Orlando - Lake Buena Vista South $119.00 plus tax Call - 407-597-4000 Registered with An Chomhdhail Na Muinteoiri Le Rinci Gaelacha Cuideachta Faoi Theorainn Rathaiochta (An Chomhdhail) www.irishdancingorg.com Charity Treble Reel for Orange County Animal Services A progressive animal-welfare focused organization that enforces the Orange County Code to protect both citizens and animals. Entry Fees: Pre Bun Grad A, Bun Grad A, B, C, $10.00 per competition Pre-Open & Open Solo Rounds $10.00 per competition Traditional Set & Treble Reel Specials $15.00 per competition Cup Award Solo Dances $15.00 per competition Open Championships $55.00 (2 solos are included in your entry) Championship change fee - $10 Facility Fee $30 per family Feisweb Fee $6 Open Platform Fee $20 Late Fee $30 The maximum fee per family is $225 plus facility fee and any applicable late, change or other fees. There will be no refund of any entry fees for any reason. Submit all entries online at https://FeisWeb.com Competitors Cards are available on FeisWeb. All registrations must be paid via PayPal Competitors are highly encouraged to print their own number prior to attending to avoid congestion at the registration table due to COVID. For those who cannot, competitor cards may be picked up at the venue. For questions contact us at our email: [email protected] or Sarah Costello TCRG on 321-200-3598 Special Needs: 1 step, any dance. -

The Frothy Band at Imminent Brewery, Northfield Minnesota on April 7Th, 7- 10 Pm

April Irish Music & 2018 Márt Dance Association Márta The mission of the Irish Music and Dance Association is to support and promote Irish music, dance, and other cultural traditions to insure their continuation. Inside this issue: IMDA Recognizes Dancers 2 Educational Grants Available Thanks You 6 For Irish Music and Dance Students Open Mic Night 7 The Irish Music and Dance Association (IMDA) would like to lend a hand to students of Irish music, dance or cultural pursuits. We’re looking for students who have already made a significant commitment to their studies, and who could use some help to get to the next level. It may be that students are ready to improve their skills (like fiddler and teacher Mary Vanorny who used her grant to study Sligo-style fiddling with Brian Conway at the Portal Irish Music Week) or it may be a student who wants to attend a special class (like Irish dancer Annie Wier who traveled to Boston for the Riverdance Academy). These are examples of great reasons to apply for an IMDA Educational Grant – as these students did in 2017. 2018 will be the twelfth year of this program, with help extended to 43 musicians, dancers, language students and artists over the years. The applicant may use the grant in any way that furthers his or her study – help with the purchase of an instrument, tuition to a workshop or class, travel expenses – the options are endless. Previous grant recipients have included musicians, dancers, Irish language students and a costume designer, but the program is open to students of other traditional Irish arts as well. -

Annual Report Tuarascáil Bhliantúil 2017 Annual Report 2017 Tuarascáil Bhliantúil 2017 ISBN: 978-1-904291-57-2

annual report tuarascáil bhliantúil 2017 Annual Report 2017 Tuarascáil Bhliantúil 2017 ISBN: 978-1-904291-57-2 The Arts Council t +353 1 618 0200 70 Merrion Square, f +353 1 676 1302 Dublin 2, D02 NY52 Ireland Callsave 1890 392 492 An Chomhairle Ealaíon www.facebook.com/artscouncilireland 70 Cearnóg Mhuirfean, twitter.com/artscouncil_ie Baile Átha Cliath 2, D02 NY52 Éire www.artscouncil.ie Trophy part-exhibition, part-performance at Barnardo Square, Dublin Fringe Festival. September 2017. Photographer: Tamara Him. taispeántas ealaíne Trophy, taibhiú páirte ag Barnardo Square, Féile Imeallach Bhaile Átha Cliath. Meán Fómhair 2017. Grianghrafadóir: Tamara Him. Body Language, David Bolger & Christopher Ash, CoisCéim Dance Theatre at RHA Gallery. November/December 2017 Photographer: Christopher Ash. Body Language, David Bolger & Christopher Ash, Amharclann Rince CoisCéim ag Gailearaí an Acadaimh Ibeirnigh Ríoga. Samhain/Nollaig 2017 Grianghrafadóir: Christopher Ash. The Arts Council An Chomhairle Ealaíon Who we are and what we do Ár ról agus ár gcuid oibre The Arts Council is the Irish government agency for Is í an Chomhairle Ealaíon an ghníomhaireacht a cheap developing the arts. We work in partnership with artists, Rialtas na hÉireann chun na healaíona a fhorbairt. arts organisations, public policy makers and others to build Oibrímid i gcomhpháirt le healaíontóirí, le heagraíochtaí a central place for the arts in Irish life. ealaíon, le lucht déanta beartas poiblí agus le daoine eile chun áit lárnach a chruthú do na healaíona i saol na We provide financial assistance to artists, arts organisations, hÉireann. local authorities and others for artistic purposes. We offer assistance and information on the arts to government and Tugaimid cúnamh airgeadais d'ealaíontóirí, d'eagraíochtaí to a wide range of individuals and organisations. -

Folklore Revival.Indb

Folklore Revival Movements in Europe post 1950 Shifting Contexts and Perspectives Edited by Daniela Stavělová and Theresa Jill Buckland 1 2 Folklore Revival Movements in Europe post 1950 Shifting Contexts and Perspectives Edited by Daniela Stavělová and Theresa Jill Buckland Institute of Ethnology of the Czech Academy of Sciences Prague 2018 3 Published as a part of the project „Tíha a beztíže folkloru. Folklorní hnutí druhé poloviny 20. století v českých zemích / Weight and Weightlessness of the Folklore. The Folklore Movement of the Second Half of the 20th Century in Czech Lands,“ supported by Czech Science Foundation GA17-26672S. Edited volume based on the results of the International Symposium Folklore revival movement of the second half of the 20th century in shifting cultural, social and political contexts organ- ized by the Institute of Ethnology in cooperation with the Academy of Performing Arts, Prague, October 18.-19., 2017. Peer review: Prof. PaedDr. Bernard Garaj, CSc. Prof. Andriy Nahachewsky, PhD. Editorial Board: PhDr. Barbora Gergelová PhDr. Jana Pospíšilová, Ph.D. PhDr. Jarmila Procházková, Ph.D. Doc. Mgr. Daniela Stavělová, CSc. PhDr. Jiří Woitsch, Ph.D. (Chair) Translations: David Mraček, Ph.D. Proofreading: Zita Skořepová, Ph.D. © Institute of Ethnology of the Czech Academy of Sciences, 2018 ISBN 978-80-88081-22-7 (Etnologický ústav AV ČR, v. v. i., Praha) 4 Table of contents: Preface . 7 Part 1 Politicizing Folklore On the Legal and Political Framework of the Folk Dance Revival Movement in Hungary in the Second Half of the Twentieth Century Lázsló Felföldi . 21 The Power of Tradition(?): Folk Revival Groups as Bearers of Folk Culture Martina Pavlicová. -

Into the Woods Is Presented Through Special Arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI)

PREMIER SPONSOR ASSOCIATE SPONSOR MEDIA SPONSOR Music and Lyrics by Book by Stephen Sondheim James Lapine June 28-July 13, 2019 Originally Directed on Broadway by James Lapine Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Original Broadyway production by Heidi Landesman Rocco Landesman Rick Steiner M. Anthony Fisher Frederic H. Mayerson Jujamcyn Theatres Originally produced by the Old Globe Theater, San Diego, CA. Scenic Design Costume Design Shoko Kambara† Megan Rutherford Lighting Design Puppetry Consultant Miriam Nilofa Crowe† Peter Fekete Sound Design Casting Director INTO The Jacqueline Herter Michael Cassara, CSA Woods Musical Director Choreographer/Associate Director Daniel Lincoln^ Andrea Leigh-Smith Production Stage Manager Production Manager Myles C. Hatch* Adam Zonder Director Michael Barakiva+ Into the Woods is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.MTIShows.com Music and Lyrics by Book by STEPHEN JAMES Directed by SONDHEIM LAPINE MICHAEL * Member of Actor’s Equity Association, † USA - Member of Originally directed on Broadway by James LapineBARAKIVA the Union of Professional Actors and United Scenic Artists Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Stage Managers in the United States. Local 829. ^ Member of American Federation of Musicians, + Local 802 or 380. CAST NARRATOR ............................................................................................................................................HERNDON LACKEY* CINDERELLA -

2014–2015 Season Sponsors

2014–2015 SEASON SPONSORS The City of Cerritos gratefully thanks our 2014–2015 Season Sponsors for their generous support of the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts. YOUR FAVORITE ENTERTAINERS, YOUR FAVORITE THEATER If your company would like to become a Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts sponsor, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at 562-916-8510. THE CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (CCPA) thanks the following current CCPA Associates donors who have contributed to the CCPA’s Endowment Fund. The Endowment Fund was established in 1994 under the visionary leadership of the Cerritos City Council to ensure that the CCPA would remain a welcoming, accessible, and affordable venue where patrons can experience the joy of entertainment and cultural enrichment. For more information about the Endowment Fund or to make a contribution, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. MARQUEE Sandra and Bruce Dickinson Diana and Rick Needham Eleanor and David St. Clair Mr. and Mrs. Curtis R. Eakin A.J. Neiman Judy and Robert Fisher Wendy and Mike Nelson Sharon Kei Frank Jill and Michael Nishida ENCORE Eugenie Gargiulo Margene and Chuck Norton The Gettys Family Gayle Garrity In Memory of Michael Garrity Ann and Clarence Ohara Art Segal In Memory Of Marilynn Segal Franz Gerich Bonnie Jo Panagos Triangle Distributing Company Margarita and Robert Gomez Minna and Frank Patterson Yamaha Corporation of America Raejean C. Goodrich Carl B. Pearlston Beryl and Graham Gosling Marilyn and Jim Peters HEADLINER Timothy Gower Gwen and Gerry Pruitt Nancy and Nick Baker Alvena and Richard Graham Mr. -

Chicago the Musical Female Characters: VELMA KELLY: Female

Chicago the Musical Female Characters: VELMA KELLY: Female, 25-45 (Range: Alto, E3-D5) Vaudeville performer who is accused of murdering her sister and husband. Hardened by fame, she cares for no one but herself and her attempt to get away with murder. ROXIE HART: Female, 25-45 (Range: Mezzo-Soprano, F3-B4) Reads and keeps up with murder trials in Chicago, and follows suit by murdering her lover, Fred Casely. She stops at nothing to render a media storm with one goal: to get away with it. She wants to be a star. MATRON "MAMA" MORTON: Female, 30-50 (Range: Alto, F#3-Bb4) Leader of the prisoners of Cook County Jail. The total essence of corruption. Accepts bribes for favors from laundry service to making calls to lawyers. “When you’re good to Moma, Moma’s good to you.” MARY SUNSHINE: Female – TYPICALLY PLAYED BY A MAN IN DRAG, 25-60 (Range: Soprano, Bb3-Bb5) Sob sister reporter from the Evening Star. Believes there is a little bit of good in everyone and will believe anything she is fed that matches her beliefs. LIZ: Female, 18-45 (Range: Ensemble, A3-C#5) Prisoner at Cook County Jail. She is imprisoned after shooting two warning shots into her husband’s head. ANNIE: Female, 18-45 (Range: Ensemble, A3-C#5) Prisoner at the Cook County Jail. Murder’s her lover after finding out he already has six wives. “One of those Mormons, ya’ know.” JUNE: Female, 18-45 (Range: Ensemble, A3-C#5) Prisoner at Cook County Jail. After her husband accuses her of screwing the milk man, he mysteriously runs into her knife… ten times. -

Round Dances Scot Byars Started Dancing in 1965 in the San Francisco Bay Area

Syllabus of Dance Descriptions STOCKTON FOLK DANCE CAMP – 2016 – FINAL 7/31/2016 In Memoriam Floyd Davis 1927 – 2016 Floyd Davis was born and raised in Modesto. He started dancing in the Modesto/Turlock area in 1947, became one of the teachers for the Modesto Folk Dancers in 1955, and was eventually awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award for dance by the Stanislaus Arts Council. Floyd loved to bake and was famous for his Chocolate Kahlua cake, which he made every year to auction off at the Stockton Folk Dance Camp Wednesday auction. Floyd was tireless in promoting folk dancing and usually danced three times a week – with the Del Valle Folk Dancers in Livermore, the Modesto Folk Dancers and the Village Dancers. In his last years, Alzheimer’s disease robbed him of his extensive knowledge and memory of hundreds, if not thousands, of folk dances. A celebration for his 89th birthday was held at the Carnegie Arts Center in Turlock on January 29 and was attended by many of his well-wishers from all over northern California. Although Floyd could not attend, a DVD was made of the event and he was able to view it and he enjoyed seeing familiar faces from his dancing days. He died less than a month later. Floyd missed attending Stockton Folk Dance Camp only once between 1970 and 2013. Sidney Messer 1926 – 2015 Sidney Messer died in November, 2015, at the age of 89. Many California folk dancers will remember his name because theny sent checks for their Federation membership to him for nine years. -

The Nineteenth-Century Russian Gypsy Choir and the Performance of Otherness

The Nineteenth-Century Russian Gypsy Choir and the Performance of Otherness Erik R. Scott Summer 2008 Erik R. Scott is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History, at the University of California, Berkeley Acknowledgments I would like to thank Professor Victoria Frede and my fellow graduate students in her seminar on Imperial Russian History. Their careful reading and constructive comments were foremost in my mind as I conceptualized and wrote this paper, first for our seminar in spring 2006, now as a revised work for publication. Abstract: As Russia’s nineteenth-century Gypsy craze swept through Moscow and St. Petersburg, Gypsy musicians entertained, dined with, and in some cases married Russian noblemen, bureaucrats, poets, and artists. Because the Gypsies’ extraordinary musical abilities supposedly stemmed from their unique Gypsy nature, the effectiveness of their performance rested on the definition of their ethnic identity as separate and distinct from that of the Russian audience. Although it drew on themes deeply embedded in Russian— and European—culture, the Orientalist allure of Gypsy performance was in no small part self-created and self-perpetuated by members of Russia’s renowned Gypsy choirs. For it was only by performing their otherness that Gypsies were able to seize upon their specialized role as entertainers, which gave this group of outsiders temporary control over their elite Russian audiences even as the songs, dances, costumes, and gestures of their performance were shaped perhaps more by audience expectations than by Gypsy musical traditions. The very popularity of the Gypsy musical idiom and the way it intimately reflected the Russian host society would later bring about a crisis of authenticity that by the end of the nineteenth century threatened the magical potential of Gypsy song and dance by suggesting it was something less than the genuine article. -

GYPSY CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS: • Momma Rose

GYPSY CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS: • Momma Rose (age from 35 - 50) The ultimate stage mother. Lives her life vicariously through her two daughters, whom she's put into show business. She is loud, brash, pushy and single- minded, but at times can be doting and charming. She is holding down demons of her own that she is afraid to face. Her voice is the ultimate powerful Broadway belt. Minimal dance but must move well. Comic timing a must. Strong Mezzo/Alto with good low notes and belt. • Baby June (age 9-10) is a Shirley Temple-like up-and-coming vaudeville star, and Madam Rose's youngest daughter. Her onstage demeanor is sugary-sweet, cute, precocious and adorable to the nth degree. Needs to be no taller than 3', 5". An adorable character - Mama Rose's shining star. Strong child singer, strong dancer. Mezzo. • Young Louise (about 12) She should look a couple years older than Baby June. She is Madam Rose's brow-beaten oldest daughter, and has always played second fiddle to her baby sister. She is shy, awkward, a little sad and subdued; she doesn't have the confidence of her sister. Strong acting skills needed. The character always dances slightly out of step but the actress playing this part must be able to dance. Mezzo singer. • Herbie (about 45) agent for Rose's children and Rose's boyfriend and a possible husband number 4. He has a heart of gold but also has the power to defend the people he loves with strength. Minimum dance. A Baritone, sings in one group number, two duets and trio with Rose and Louise. -

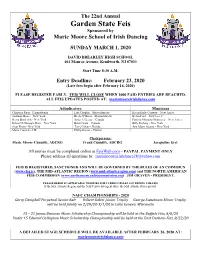

2020 Syllabus

The 22nd Annual Garden State Feis Sponsored by Marie Moore School of Irish Dancing SUNDAY MARCH 1, 2020 DAVID BREARLEY HIGH SCHOOL 401 Monroe Avenue, Kenilworth, NJ 07033 Start Time 8:30 A.M. Entry Deadline: February 23, 2020 (Late fees begin after February 16, 2020) PLEASE REGISTER EARLY. FEIS WILL CLOSE WHEN 1000 PAID ENTRIES ARE REACHED. ALL FEIS UPDATES POSTED AT: mariemooreirishdance.com Adjudicators Musicians Christina Ryan - Pennsylvania Lisa Chaplin – Massachusetts Karen Early-Conway – New Jersey Siobhan Moore - New York Breda O’Brien – Massachusetts Kevin Ford – New Jersey Kerry Broderick - New York Jackie O’Leary – Canada Patricia Moriarty-Morrissey – New Jersey Eileen McDonagh-Morr – New York Brian Grant – Canada Billy Furlong - New York Sean Flynn - New York Terry Gillan – Florida Ann Marie Acosta – New York Marie Connell – UK Philip Owens – Florida Chairpersons: Marie Moore-Cunniffe, ADCRG Frank Cunniffe, ADCRG Jacqueline Erel All entries must be completed online at FeisWeb.com – PAYPAL PAYMENT ONLY Please address all questions to: [email protected] FEIS IS REGISTERED, SANCTIONED AND WILL BE GOVERNED BY THE RULES OF AN COIMISIUN (www.clrg.ie), THE MID-ATLANTIC REGION (www.mid-atlanticregion.com) and THE NORTH AMERICAN FEIS COMMISSION (www.northamericanfeiscommission.org) JIM GRAVEN - PRESIDENT. PLEASE REFER TO APPLICABLE WEBSITES FOR CURRENT RULES GOVERNING THE FEIS If the Mid-Atlantic Region and the NAFC have divergent rules, the Mid-Atlantic Rules prevail. NAFC CHAMPIONSHIPS - 2020 Gerry Campbell Perpetual