SKOPAS PART 1-2 017-318 New Layout 1 10/02/2014 01:03 Μμ Page 19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Medici Aphrodite Angel D

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite Angel D. Arvello Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Arvello, Angel D., "A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 2015. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2015 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A HELLENISTIC MASTERPIECE: THE MEDICI APRHODITE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Angel D. Arvello B. A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 1996 May 2005 In Memory of Marcel “Butch” Romagosa, Jr. (10 December 1948 - 31 August 1998) ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge the support of my parents, Paul and Daisy Arvello, the love and support of my husband, Kevin Hunter, and the guidance and inspiration of Professor Patricia Lawrence in addition to access to numerous photographs of hers and her coin collection. I would also like to thank Doug Smith both for his extensive website which was invaluable in writing chapter four and for his permission to reproduce the coin in his private collection. -

SEAT of the WORLD of Beautiful and Gentle Tales Are Discovered and Followed Through Their Development

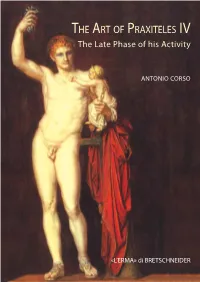

The book is focused on the late production of the 4th c. BC Athenian sculptor Praxiteles and in particular 190 on his oeuvre from around 355 to around 340 BC. HE RT OF RAXITELES The most important works of this master considered in this essay are his sculptures for the Mausoleum of T A P IV Halicarnassus, the Apollo Sauroctonus, the Eros of Parium, the Artemis Brauronia, Peitho and Paregoros, his Aphrodite from Corinth, the group of Apollo and Poseidon, the Apollinean triad of Mantinea, the The Late Phase of his Activity Dionysus of Elis, the Hermes of Olympia and the Aphrodite Pseliumene. Complete lists of ancient copies and variations derived from the masterpieces studied here are also provided. The creation by the artist of an art of pleasure and his visual definition of a remote and mythical Arcadia SEAT OF THE WORLD of beautiful and gentle tales are discovered and followed through their development. ANTONIO CORSO Antonio Corso attended his curriculum of studies in classics and archaeology in Padua, Athens, Frank- The Palatine of Ancient Rome furt and London. He published more than 100 scientific essays (articles and books) in well refereed peri- ate Phase of his Activity Phase ate odicals and series of books. The most important areas covered by his studies are the ancient art criticism L and the knowledge of classical Greek artists. In particular he collected in three books all the written tes- The The timonia on Praxiteles and in other three books he reconstructed the career of this sculptor from around 375 to around 355 BC. -

Paria Lithos and Its Employment in Sculpture, Architecture and Epigraphy from Antiquity Till the 19Th C

IIEPIEXOMENA - CONTENTS Eioaycoytj 13 Foreword 19 i'sg -Abbreviations 22 MEPOE 1 - PART 1 AATOMEIA KAI EPrASTHPIA TAYnTIKHZ TH2 ITAPOY QUARRIES AND MARBLE WORKSHOPS OF PAROS 1. Norman Herz The Classical Marble Quarries of Paros: Paros-1, Paros-2 and Paros-3 27 2. Demetrius Schilardi Observations on the Quarries of Spilies, Lakkoi and Thapsana on Paros 35 3. MavwXris Kogge; Yiroyeia Aaxoneia trig ndoou 61 4. Povoetog Aeißaödgog xai KoivatavTiva Todiuov Nea STOIXEICI yia TT]V Yjioyeia EKnetd^Xeuari xov AUXVITT] crtr|v ridgo 83 5. Matthias Bruno The Results of a Field Survey on Paros 91 6. Matthias Bruno, Lorenzo Lazzarini, Michele Soligo, Bruno Turi, Myrsine Varti-Matarangas The Ancient Quarry at Karavos (Paros) and the Characterization of its Marble 95 7. KXaigrt Evatgatiov EpyacrtriQia Y\VKIVWC\C, axx\v naooixi'a üäoou 105 8. ÄyyeXos MatGaiov VpognöAeeoq 113 9. Kenneth Sheedy Archaic Parian Coinage and Parian Marble 117 MEPOE 2 - PART 2 H nAPIA AI0O2 KAI H XPHZH THZ 2THN TAYIITIKH, APXITEKTONIKH KAI EnirPAd>IKH AnO THN APXAIOTHTA MEXPI TON 19° AI. M.X. PARIA LITHOS AND ITS EMPLOYMENT IN SCULPTURE, ARCHITECTURE AND EPIGRAPHY FROM ANTIQUITY TILL THE 19TH C. A.D. 10. Gottfried Gruben Marmor und Architektur 125 11. Richard Tomlinson Towards a Distribution Pattern for Parian Marble in the Architecture of the 6th c. B.C 139 12. Georgia Kokkorou-AIevras The Use and Distribution of Parian Marble during the Archaic Period 143 13. Kategiva Mauoaydvi] napaniQTio£i5 oxr\v AQxaioTEgr] Tc«ptXT] STTJXT] XOV Mouoei'ou Tldgov 155 14. AimtJTgtig Exi^aovu ta TOV 2T]UEic6aeig Y Hniepyo KOQIAO ABXTITTJ xr]g nctQOD 163 15. -

Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art 7-1-2000 Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures] J.L. Benson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Benson, J.L., "Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures]" (2000). Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements. 1. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cover design by Jeff Belizaire About this book This is one part of the first comprehensive study of the development of Greek sculpture and painting with the aim of enriching the usual stylistic-sociological approaches through a serious, disciplined consideration of the basic Greek scientific orientation to the world. This world view, known as the Four Elements Theory, came to specific formulation at the same time as the perfected contrapposto of Polykleitos and a concern with the four root colors in painting (Polygnotos). All these factors are found to be intimately intertwined, for, at this stage of human culture, the spheres of science and art were not so drastically differentiated as in our era. The world of the four elements involved the concepts of polarity and complementarism at every level. -

NEW EOT-English:Layout 1

TOUR OF ATHENS, stage 10 FROM OMONIA SQUARE TO KYPSELI Tour of Athens, Stage 10: Papadiamantis Square), former- umental staircases lead to the 107. Bell-shaped FROM MONIA QUARE ly a garden city (with villas, Ionian style four-column propy- idol with O S two-storey blocks of flats, laea of the ground floor, a copy movable legs TO K YPSELI densely vegetated) devel- of the northern hall of the from Thebes, oped in the 1920’s - the Erechteion ( page 13). Boeotia (early 7th century suburban style has been B.C.), a model preserved notwithstanding 1.2 ¢ “Acropol Palace” of the mascot of subsequent development. Hotel (1925-1926) the Athens 2004 Olympic Games A five-story building (In the photo designed by the archi- THE SIGHTS: an exact copy tect I. Mayiasis, the of the idol. You may purchase 1.1 ¢Polytechnic Acropol Palace is a dis- tinctive example of one at the shops School (National Athens Art Nouveau ar- of the Metsovio Polytechnic) Archaeological chitecture. Designed by the ar- Resources Fund – T.A.P.). chitect L. Kaftan - 1.3 tzoglou, the ¢Tositsa Str Polytechnic was built A wide pedestrian zone, from 1861-1876. It is an flanked by the National archetype of the urban tra- Metsovio Polytechnic dition of Athens. It compris- and the garden of the 72 es of a central building and T- National Archaeological 73 shaped wings facing Patision Museum, with a row of trees in Str. It has two floors and the the middle, Tositsa Str is a development, entrance is elevated. Two mon- place to relax and stroll. -

THE APOXYOMENOS of LYSIPPUS. in the Hellenic Journal for 1903

THE APOXYOMENOS OF LYSIPPUS. IN the Hellenic Journal for 1903, while publishing some heads of Apollo, I took occasion to express my doubts as to the expediency of hereafter taking the Apoxyomenos as the norm of the works of Lysippus. These views, how- ever, were not expressed in any detail, and occurring at the end of a paper devoted to other matters, have not attracted much attention from archaeolo- gists. The subject is of great importance, since if my contention be justified, much of the history of Greek sculpture in the fourth century will have to be reconsidered. Being still convinced of the justice of the view which I took two years ago, I feel bound to bring it forward in more detail and with a fuller statement of reasons. Our knowledge of many of the sculptors of the fourth century, Praxiteles, Scopas, Bryaxis, Timotheus, and others, has been enormously enlarged during the last thirty years through our discovery of works proved by documentary evidence to have been either actually executed by them, or at least made under their direction. But in the case of Lysippus no such discovery was made until the very important identification of the Agias at Delphi as a copy of a statue by this master. Hitherto we had been content to take the Apoxyomenos as the best indication of Lysippic style ; and apparently few archaeologists realized how slender was the evidence on which its assignment to Lysippus was based. That assignment took place many years ago, when archaeological method was lax ; and it has not been subjected to sufficiently searching criticism. -

Iconography of the Gorgons on Temple Decoration in Sicily and Western Greece

ICONOGRAPHY OF THE GORGONS ON TEMPLE DECORATION IN SICILY AND WESTERN GREECE By Katrina Marie Heller Submitted to the Faculty of The Archaeological Studies Program Department of Sociology and Archaeology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science University of Wisconsin-La Crosse 2010 Copyright 2010 by Katrina Marie Heller All Rights Reserved ii ICONOGRAPHY OF THE GORGONS ON TEMPLE DECORATION IN SICILY AND WESTERN GREECE Katrina Marie Heller, B.S. University of Wisconsin - La Crosse, 2010 This paper provides a concise analysis of the Gorgon image as it has been featured on temples throughout the Greek world. The Gorgons, also known as Medusa and her two sisters, were common decorative motifs on temples beginning in the eighth century B.C. and reaching their peak of popularity in the sixth century B.C. Their image has been found to decorate various parts of the temple across Sicily, Southern Italy, Crete, and the Greek mainland. By analyzing the city in which the image was found, where on the temple the Gorgon was depicted, as well as stylistic variations, significant differences in these images were identified. While many of the Gorgon icons were used simply as decoration, others, such as those used as antefixes or in pediments may have been utilized as apotropaic devices to ward off evil. iii Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my family and friends for all of their encouragement throughout this project. A special thanks to my parents, Kathy and Gary Heller, who constantly support me in all I do. I need to thank Dr Jim Theler and Dr Christine Hippert for all of the assistance they have provided over the past year, not only for this project but also for their help and interest in my academic future. -

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period Ryan

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period by Ryan Anthony Boehm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emily Mackil, Chair Professor Erich Gruen Professor Mark Griffith Spring 2011 Copyright © Ryan Anthony Boehm, 2011 ABSTRACT SYNOIKISM, URBANIZATION, AND EMPIRE IN THE EARLY HELLENISTIC PERIOD by Ryan Anthony Boehm Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology University of California, Berkeley Professor Emily Mackil, Chair This dissertation, entitled “Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period,” seeks to present a new approach to understanding the dynamic interaction between imperial powers and cities following the Macedonian conquest of Greece and Asia Minor. Rather than constructing a political narrative of the period, I focus on the role of reshaping urban centers and regional landscapes in the creation of empire in Greece and western Asia Minor. This period was marked by the rapid creation of new cities, major settlement and demographic shifts, and the reorganization, consolidation, or destruction of existing settlements and the urbanization of previously under- exploited regions. I analyze the complexities of this phenomenon across four frameworks: shifting settlement patterns, the regional and royal economy, civic religion, and the articulation of a new order in architectural and urban space. The introduction poses the central problem of the interrelationship between urbanization and imperial control and sets out the methodology of my dissertation. After briefly reviewing and critiquing previous approaches to this topic, which have focused mainly on creating catalogues, I point to the gains that can be made by shifting the focus to social and economic structures and asking more specific interpretive questions. -

The Impact of EU Structural Funds on Greece Liargovas, Panagiotis (Ed.); Petropoulos, Sotiris (Ed.); Tzifakis, Nikolaos (Ed.); Huliaras, Asteris (Ed.)

www.ssoar.info Beyond "Absorption": the Impact of EU Structural Funds on Greece Liargovas, Panagiotis (Ed.); Petropoulos, Sotiris (Ed.); Tzifakis, Nikolaos (Ed.); Huliaras, Asteris (Ed.) Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Sammelwerk / collection Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Liargovas, P., Petropoulos, S., Tzifakis, N., & Huliaras, A. (Eds.). (2015). Beyond "Absorption": the Impact of EU Structural Funds on Greece. Sankt Augustin: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168- ssoar-456316 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-NC Licence Nicht-kommerziell) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu (Attribution-NonCommercial). For more Information see: den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/deed.de Hellenic University Association Auslandsbüro Griechenland for European Studies Αντιπροσωπεία στην Ελλάδα Beyond "Absorption": The Impact of EU Structural Funds on Greece Panagiotis Liargovas, Sotiris Petropoulos, Nikolaos Tzifakis and Asteris Huliaras www.kas.de/greece Published by the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. © 2015, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin/Berlin All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanically, without written permission of the publisher. ISBN 978-3-95721-182-8 This research has been co-financed by the European Union (European Social Fund – ESF) and Greek national funds through the Operational Program “Education and Lifelong Learning” of the National Strategic Reference Framework (NSRF) - Research Funding Program: EXCELLENCE (ARISTEIA) – Re-Considering the Political Impact of the Structural Funds on Greece. -

AP Art History Greek Study Guide

AP Art History Greek Study Guide "I cannot teach anybody anything. I can only make them think." - Socrates (470-399 BCE) CH. 5 (p. 101 – 155) Textbook Timeline Geometric Archaic Early Classical High Classical Late Classical Hellenistic 900-700 600 BCE- 480 Severe 450 BCE-400 BCE 400-323 BCE 323 BCE-31 BCE BCE 480 BCE- 450 BCE BCE Artists: Phidias, Artists: Praxiteles, Artists: Pythokritos, Artists: ??? Polykleitos, Myron Scopas, Orientalizing Lysippus Polydorus, Artists: Kritios 700-600 Agesander, Artworks: Artworks: BCE Artworks: Athenodorus kouroi and Artworks: Riace warrior, Aphrodite of Knidos, korai Pedimental Zeus/Poseidon, Hermes & the Infant Artworks: sculpture of the Doryphoros, Dionysus, Dying Gaul, Temple of Diskobolos, Nike Apoxyomenos, Nike of Samothrace, Descriptions: Aphaia and the Adjusting her Farnes Herakles Barberini Faun, Idealization, Temple of Sandal Seated Boxer, Old Market Woman, Artemis, Descriptions: stylized, Laocoon & his Sons FRONTAL, Kritios boy Descriptions: NATURAL, humanized, rigid Idealization, relaxed, Descriptions: unemotional, elongation EMOTIONAL, Descriptions: PERFECTION, dramatic, Contrapposto, self-contained exaggeration, movement movement, individualistic Vocabulary 1. Acropolis 14. Frieze 27. Pediment 2. Agora 15. Gigantomachy 28. Peplos 3. Amphiprostyle 16. Isocephalism 29. Peristyle 4. Amphora 17. In Situ 30. Portico 5. Architrave 18. Ionic 31. Propylaeum 6. Athena 19. Kiln 32. Relief Sculpture 7. Canon 20. Kouros / Kore 33. Shaft 8. Caryatid / Atlantid 21. Krater 34. Stele 9. Contrapposto 22. Metope 35. Stoa 10. Corinthian 23. Mosaic 36. Tholos 11. Cornice 24. Nike 37. Triglyph 12. Doric 25. Niobe 38. Zeus 13. Entablature 26. Panatheonic Way To-do List: ● Know the key ideas, vocabulary, & dates ● Complete the notes pages / Study Guides / any flashcards you may want to add to your ongoing stack ● Visit Khan Academy Image Set Key Ideas *Athenian Agora ● Greeks are interested in the human figure the idea of Geometric perfection. -

Downloadable

EXPERT-LED PETER SOMMER ARCHAEOLOGICAL & CULTURAL TRAVELS TOURS & GULET CRUISES 2021 PB Peter Sommer Travels Peter Sommer Travels 1 WELCOME WHY TRAVEL WITH US? TO PETER SOMMER TR AVELS Writing this in autumn 2020, it is hard to know quite where to begin. I usually review the season just gone, the new tours that we ran, the preparatory recces we made, the new tours we are unveiling for the next year, the feedback we have received and our exciting plans for the future. However, as you well know, this year has been unlike any other in our collective memory. Our exciting plans for 2020 were thrown into disarray, just like many of yours. We were so disappointed that so many of you were unable to travel with us in 2020. Our greatest pleasure is to share the destinations we have grown to love so deeply with you our wonderful guests. I had the pleasure and privilege of speaking with many of you personally during the 2020 season. I was warmed and touched by your support, your understanding, your patience, and your generosity. All of us here at PST are extremely grateful and heartened by your enthusiasm and eagerness to travel with us when it becomes possible. PST is a small, flexible, and dynamic company. We have weathered countless downturns during the many years we have been operating. Elin, my wife, and I have always reinvested in the business with long term goals and are very used to surviving all manner of curve balls, although COVID-19 is certainly the biggest we have yet faced. -

Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: a Socio-Cultural Perspective

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective Nicholas D. Cross The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1479 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INTERSTATE ALLIANCES IN THE FOURTH-CENTURY BCE GREEK WORLD: A SOCIO-CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE by Nicholas D. Cross A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 Nicholas D. Cross All Rights Reserved ii Interstate Alliances in the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective by Nicholas D. Cross This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________ __________________________________________ Date Jennifer Roberts Chair of Examining Committee ______________ __________________________________________ Date Helena Rosenblatt Executive Officer Supervisory Committee Joel Allen Liv Yarrow THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective by Nicholas D. Cross Adviser: Professor Jennifer Roberts This dissertation offers a reassessment of interstate alliances (συµµαχία) in the fourth-century BCE Greek world from a socio-cultural perspective.