Parting Ways

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justice Jackson and the Second Flag-Salute Case: Reason and Passion in Opinion Writing

University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2011 Justice Jackson and the Second Flag-Salute Case: Reason and Passion in Opinion Writing Douglas E. Abrams University of Missouri School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/facpubs Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Douglas E. Abrams, Justice Jackson and the Second Flag-Salute Case: Reason and Passion in Opinion Writing, 36 Journal of Supreme Court History 30 (2011). Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/facpubs/890 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Legal Studies Research Paper Series Research Paper No. 2015-01 Justice Jackson and the Second Flag-Salute Case: Reason and Passion in Opinion Writing Douglas E. Abrams 36 JOURNAL OF SUPREME COURT HISTORY 30 (2011) This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Sciences Research Network Electronic Paper Collection at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2547781 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2547781 Justice Jackson and the Second Flag-Salute Case: Reason and Passion In Opinion Writing by Douglas E. Abrams University of Missouri School of Law (36 JOURNAL OF SUPREME COURT HISTORY 30 (2011)) Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2547781 Justice Jackson and the Second Flag-Salute Case: Reason and Passion In Judicial Opinion Writing I. -

Der Imagewandel Von Helmut Kohl, Gerhard Schröder Und Angela Merkel Vom Kanzlerkandidaten Zum Kanzler - Ein Schauspiel in Zwei Akten

Forschungsgsgruppe Deutschland Februar 2008 Working Paper Sybille Klormann, Britta Udelhoven Der Imagewandel von Helmut Kohl, Gerhard Schröder und Angela Merkel Vom Kanzlerkandidaten zum Kanzler - Ein Schauspiel in zwei Akten Inszenierung und Management von Machtwechseln in Deutschland 02/2008 Diese Veröffentlichung entstand im Rahmen eines Lehrforschungsprojektes des Geschwister-Scholl-Instituts für Politische Wissenschaft unter Leitung von Dr. Manuela Glaab, Forschungsgruppe Deutschland am Centrum für angewandte Politikforschung. Weitere Informationen unter: www.forschungsgruppe-deutschland.de Inhaltsverzeichnis: 1. Die Bedeutung und Bewertung von Politiker – Images 3 2. Helmut Kohl: „Ich werde einmal der erste Mann in diesem Lande!“ 7 2.1 Gut Ding will Weile haben. Der „Lange“ Weg ins Kanzleramt 7 2.2 Groß und stolz: Ein Pfälzer erschüttert die Bonner Bühne 11 2.3 Der richtige Mann zur richtigen Zeit: Der Mann der deutschen Mitte 13 2.4 Der Bauherr der Macht 14 2.5 Kohl: Keine Richtung, keine Linie, keine Kompetenz 16 3. Gerhard Schröder: „Ich will hier rein!“ 18 3.1 „Hoppla, jetzt komm ich!“ Schröders Weg ins Bundeskanzleramt 18 3.2 „Wetten ... dass?“ – Regieren macht Spass 22 3.3 Robin Hood oder Genosse der Bosse? Wofür steht Schröder? 24 3.4 Wo ist Schröder? Vom „Gernekanzler“ zum „Chaoskanzler“ 26 3.5 Von Saumagen, Viel-Sagen und Reformvorhaben 28 4. Angela Merkel: „Ich will Deutschland dienen.“ 29 4.1 Fremd, unscheinbar und unterschätzt – Merkels leiser Aufstieg 29 4.2 Die drei P’s der Merkel: Physikerin, Politikerin und doch Phantom 33 4.3 Zwischen Darwin und Deutschland, Kanzleramt und Küche 35 4.4 „Angela Bangbüx“ : Versetzung akut gefährdet 37 4.5 Brutto: Aus einem Guss – Netto: Zuckerguss 39 5. -

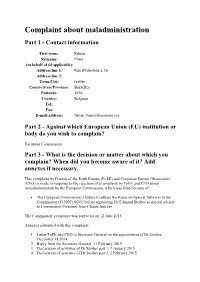

Complaint About Maladministration Part 1 - Contact Information

Complaint about maladministration Part 1 - Contact information First name: Fabian Surname: Flues On behalf of (if applicable): Address line 1: Rue d'Edimbourg 26 Address line 2: Town/City: Ixelles County/State/Province: Bruxelles Postcode: 1050 Country: Belgium Tel.: Fax: E-mail address: [email protected] Part 2 - Against which European Union (EU) institution or body do you wish to complain? European Commission Part 3 - What is the decision or matter about which you complain? When did you become aware of it? Add annexes if necessary. This complaint by Friends of the Earth Europe (FoEE) and Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO) is made in response to the rejection of a complaint by FoEE and CEO about maladministration by the European Commission, which was filed because of: The European Commission’s failure to adhere the Rules on Special Advisers to the Commission (C(2007) 6655) before appointing Dr Edmund Stoiber as special adviser to Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker The Commission’s response was sent to us on 12 June 2015. Annexes submitted with this complaint: 1. Letter FoEE and CEO to Secretary General on the appointment of Dr Stoiber, December 18 2014 2. Reply from the Secretary General, 11 February 2015 3. Declaration of activities of Dr Stoiber part 1, 7 January 2015 4. Declaration of activities of Dr Stoiber part 2, 2 February 2015 5. Declaration of honour of Dr Stoiber 7 January 2015 6. Response Secretary General to FoEE and CEO questions, 16 February 2015 7. Letter FoEE and CEO to Secretary General requesting reconsideration, 25 May 2015 8. -

Winfried Kretschmann – Grüne Bodenhaftung Schmunzelt Sich Ins Schwarz-Gelbe Revier … Lambertz Kalender 2018 „LIFE IS a DANCE“

Ausgabe 14 Journal 11. Jahrgang · Session 2018 2018 Der Zentis Kinder karne- vals preis geht 2018 gleich an zwei Vereine für ihre tolle Nachwuchsarbeit 55 Objekte erzählen A achens Geschichte: Neu erschienenes Buch der Sammlung Crous Mitreißend: Prinz Mike I. und sein Hofstaat bieten anrühren des Prinzenspiel Unser 69. Ritter WIDER DEN TIERISCHEN ERNST: Winfried Kretschmann – grüne Bodenhaftung schmunzelt sich ins schwarz-gelbe Revier … Lambertz Kalender 2018 „LIFE IS A DANCE“ www.lambertz.de Editorial Journal 14 | 2018 3 Liebe Freunde des Öcher Fastelovvends und des , Neben einem großartigen Sessions tischen Bühne hier beim Tierischen auftakt am 11.11.2017 in den Casino Ernst h aben wird. Als ehemaliger Räumen der AachenMünchener er Öcher Prinz und AKV Präsident hat lebte der neue Aachener Prinz Mike I. unser Verein ihm viel zu verdanken. gemeinsam mit seinem Hof staat und Wir danken für die Jahre, in denen er einem restlos begeisterten Publi die Verkörperung des Lennet Kann auf kum eine ebenso grandiose Prinzen den Aachener Bühnen war. pro klamatio n, die wiederum über f acebook und – ganz neu – auch über Abschied genommen haben wir im YouTube live übertragen wurde. Die letzten Jahr unter anderem von unse positive Resonanz hat uns begeistert. rem langjährigen Ordenskanzler Danke hierfür an alle Sponsoren und C onstantin Freiherr Heereman von Unterstützer des AKV! Zuydtwyck, unserem Ritter Heiner Geißler und unserem Senator Karl Freuen können wir uns auch auf un Schumacher. Wir halten sie und alle seren neuen Ritter 2018. Winfried anderen in bleibender Erinnerung Kretschmann ist ein völlig atypischer und gedenken ihrer auch durch un Politiker: ein Grüner, der seinen Daim ser sozia les Engagement, getreu dem ler liebt, ein aufrechter Pazifist, der Motto: „Durch Frohsinn zur Wohltä Das Wahljahr 2017 war vorüber und Mitglied im örtlichen Schützenver tigkeit“. -

National Security Council Eisenhower Executive Office Building, Washington, DC 20504 Phone, 202–456–1414

92 U.S. GOVERNMENT MANUAL For further information, contact the Information Office, Council on Environmental Quality, 722 Jackson Place NW., Washington, DC 20503. Phone, 202–395–5750. Fax, 202–456–2710. Internet, www.whitehouse.gov/ceq. National Security Council Eisenhower Executive Office Building, Washington, DC 20504 Phone, 202–456–1414 Members: The President GEORGE W. BUSH The Vice President DICK CHENEY The Secretary of State CONDOLEEZZA RICE The Secretary of Defense ROBERT M. GATES Statutory Advisers: Director of National Intelligence MIKE MCCONNELL Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff ADM. MICHAEL G. MULLEN, USN Standing Participants: The Secretary of the Treasury HENRY M. PAULSON, JR. Chief of Staff to the President JOSHUA B. BOLTEN Counsel to the President FRED FIELDING Assistant to the President for National Security STEPHEN J. HADLEY Affairs Assistant to the President for Economic Policy KEITH HENNESSEY Officials: Assistant to the President for National Security STEPHEN J. HADLEY Affairs Assistant to the President for National Security JAMES F. JEFFREY Affairs and Deputy National Security Adviser Executive Secretary JOHN I. PRAY, JR. The National Security Council was Nations, the Assistant to the President for established by the National Security Act National Security Affairs, the Assistant to of 1947, as amended (50 U.S.C. 402). the President for Economic Policy, and The Council was placed in the Executive the Chief of Staff to the President are Office of the President by Reorganization invited to all meetings of the Council. Plan No. 4 of 1949 (5 U.S.C. app.). The Attorney General and the Director The National Security Council is of National Drug Control Policy are chaired by the President. -

The Aspen Institute Germany ANNUAL REPORT 2007 2008 the Aspen Institute 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2007 2008 the Aspen Institute ANNUAL REPORT 2007 3 2008

The Aspen Institute Germany ANNUAL REPORT 2007 2008 The Aspen Institute 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2007 2008 The Aspen Institute ANNUAL REPORT 2007 3 2008 Dear Friend of the Aspen Institute In the following pages you will find a report on the Aspen Institute Germany’s activities for the years 2007 and 2008. As you may know, the Aspen Institute Germany is a non-partisan, privately supported organization dedicated to values-based leadership in addressing the toughest policy challenges of the day. As you will see from the reports on the Aspen European Strategy Forum, Iran, Syria, Lebanon and the Balkans that follow, a significant part of Aspen’s current work is devoted to promoting dialogue between key stakeholders on the most important strategic issues and to building lasting ties and constructive exchanges between leaders in North America, Europe and the Near East. The reports on the various events that Aspen convened in 2007 and 2008 show how Aspen achieves this: by bringing together interdisciplinary groups of decision makers and experts from business, academia, politics and the arts that might otherwise not meet. These groups are convened in small-scale conferences, seminars and discussion groups to consider complex issues in depth, in the spirit of neutrality and open mindedness needed for a genuine search for common ground and viable solutions. The Aspen Institute organizes a program on leadership development. In the course of 2007 and 2008, this program brought leaders from Germany, Lebanon, the Balkans and the United States of America together to explore the importance of values-based leadership together with one another. -

Diplomacy for the 21St Century: Transformational Diplomacy

Order Code RL34141 Diplomacy for the 21st Century: Transformational Diplomacy August 23, 2007 Kennon H. Nakamura and Susan B. Epstein Foreign Policy Analysts Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Diplomacy for the 21st Century: Transformational Diplomacy Summary Many foreign affairs experts believe that the international system is undergoing a momentous transition affecting its very nature. Some, such as former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, compare the changes in the international system to those of a century ago. Secretary of State Rice relates the changes to the period following the Second World War and the start of the Cold War. At the same time, concerns are being raised about the need for major reform of the institutions and tools of American diplomacy to meet the coming challenges. At issue is how the United States adjusts its diplomacy to address foreign policy demands in the 21st Century. On January 18, 2006, in a speech at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., Secretary Rice outlined her vision for diplomacy changes that she referred to as “transformational diplomacy” to meet this 21st Century world. The new diplomacy elevates democracy-promotion activities inside countries. According to Secretary Rice in her February 14, 2006 testimony before Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the objective of transformational diplomacy is: “to work with our many partners around the world to build and sustain democratic, well-governed states that will respond to the needs of their people and conduct themselves responsibly in the international system.” Secretary Rice’s announcement included moving people and positions from Washington, D.C., and Europe to “strategic” countries; it also created a new position of Director of Foreign Assistance, modified the tools of diplomacy, and changed U.S. -

Bulletin of the Institute for Western Affairs, Ed. 25

BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE FOR WESTERN AFFAIRS 75 years of the CDU Piotr Kubiak, Martin Wycisk The Christian Democratic Union (CDU) celebrated its 75th anniversary on June 26, 2020. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the celebrations were subdued. Together with its sister party CSU, the CDU has become a fixture on the political landscape of the Federal Republic of Germany: from Adenauer to Merkel, no other German party has exerted bigger influence on the fates of its country. The most prominent achievements credited to the Christian democrats are to have strengthened democracy in Editorial Board: Germany and the country’s social market economy, and to have Radosław Grodzki contributed to cooperation with the West, the reunification of Karol Janoś (editor in chief) Germany and European integration. What is more, the CDU is Piotr Kubiak thought of as the party in power: for 51 out of 71 years of its Krzysztof Malinowski existence, the CDU was in the government. 5 out of 8 German chancellors came from among the ranks of the CDU as did 6 out of 12 of the country’s presidents. Christian Democratic parties have won 16 of the total of 19 Bundestag election. Is it there- fore fair to proclaim the success of the Christian Democrats as No. 25(445)/2020 being complete? Has the CDU not lost any of its appeal during 09.07.2020 its 75 years in existence? What are the challenges and problems ISSN 2450-5080 that the CDU is facing in 2020? What future looms ahead for the party as it faces the challenges of the modern world and the choice of new leadership? The Adenauer period The Bulletin is also available on: NEWSLETTER IZ The CDU emerged in the wake of the defeat of the Third Reich, FACEBOOK SCRIBD driven by the need to revive political life in occupied Germany. -

German Elections of 2002: Aftermath and Implications for the United States

Order Code RL31586 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web German Elections of 2002: Aftermath and Implications for the United States September 27, 2002 name redacted Specialist in International Relations Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress German Elections of 2002: Aftermath and Implications for the United States Summary The German parliamentary elections of September 22, 2002, returned Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder and his Red-Green coalition by the narrowest of margins. The Chancellor begins his second term weakened by the slimness of his coalition’s majority in parliament and the lack of a clear mandate from the voters. He must deal with serious economic problems left over from his first term. He also faces the challenge of overcoming tensions with the United States brought on by his sharp campaign statements condemning U.S. Iraq policy that may have won him the election. Many now wonder whether Schroeder will exercise fiscal discipline and take unpopular steps needed to restructure the economy. The EU is at a critical stage in its further evolution and needs Germany’s very active leadership to meet the challenges of enlargement and continued progress as an economic and political entity. Here, Germany’s economic stagnation and domestic preoccupations could hurt. EU efforts to move forward on the European Security and Defense Policy (ESDP) are also affected by a need for Germany’s action. Germany supports ESDP but unless it increases its defense spending substantially, no serious European defense capability is likely. Germany is a primary supporter of the EU’s further enlargement. -

DER SPIEGEL Jahrgang 1999 Heft 46

Werbeseite Werbeseite DAS DEUTSCHE NACHRICHTEN-MAGAZIN Hausmitteilung 15. November 1999 Betr.: Korrespondenten, Scharping, Belgrad er SPIEGEL als auf- Dlagenstärkstes Nach- richten-Magazin Europas hat auch eine stattliche Zahl von Berichterstat- tern in aller Welt: Zu ei- nem Korrespondenten- treffen reisten vergangene Woche 26 Kollegen aus 22 Auslandsbüros nach Ham- burg. Einige waren etwas länger unterwegs – sie ka- men aus Peking, Rio de Ja- neiro, Johannesburg und Tokio. Die Korresponden- M. ZUCHT / DER SPIEGEL ten kennen sich aus in SPIEGEL-Auslandskorrespondenten Kulturen, Eigenarten und Dialekten ihrer Gastländer. Neben den gängigen Weltsprachen parlieren sie auf Chi- nesisch, Japanisch, Persisch oder Türkisch, auf Hindi, Tamil und in vielen slawischen Sprachen. Sie recherchieren im indischen Andra Pradesch, wo die Menschen Telu- gu sprechen, und führen Interviews auf Hocharabisch – bei Bedarf auch im ägyp- tischen Nildialekt. er Mann, mit dem SPIEGEL-Redakteur DHajo Schumacher, 35, vor vier Jahren im Saal des Mannheimer Kongresszentrums sprach, hatte gerade seine bitterste Niederla- ge erlitten: Eben war Rudolf Scharping noch SPD-Vorsitzender gewesen, nun hatte der Parteitag überraschend Oskar Lafontaine ge- wählt. Ein Debakel. „Über meine Gefühlsla- ge bin ich mir im Unklaren“, vertraute Schar- ping dem SPIEGEL-Mann an. Sieger Lafon- M. DARCHINGER taine hat sich inzwischen geräuschvoll von Schumacher, Scharping (1995) der politischen Bühne verabschiedet, Verlie- rer Scharping aber sieht sich stärker denn je. „In Umfragen bin ich als einziger kaum gefallen“, sagte der Verteidigungsminister vergangene Woche, als Schumacher ihn im Reichstag traf, und: „Mannheim habe ich verarbeitet.“ Tatsächlich? Schumacher hegt Zweifel: „Die Verletzung ging damals viel zu tief“ (Seite 26). elgrad liegt nur eine Flugstunde von Frankfurt entfernt, aber die Reise dorthin Bdauert fast einen Tag. -

CSU-Parteivorsitzender 1945-1949

Die Parteivorsitzenden* der CSU (Stand: August 2020) Josef Müller – Landesvorsitzender 17.12.1945-28.05.1949 Hans Ehard – Landesvorsitzender 28.05.1949-22.01.1955 Hanns Seidel – Landesvorsitzender 22.01.1955-18.03.1961 Franz Josef Strauß – Landes-/Parteivorsitzender 18.03.1961-03.10.1988 Theo Waigel – Parteivorsitzender 19.11.1988-16.01.1999 Edmund Stoiber – Parteivorsitzender 16.01.1999-29.09.2007 Erwin Huber – Parteivorsitzender 29.09.2007-25.10.2008 Horst Seehofer – Parteivorsitzender 25.10.2008-19.01.2019 Markus Söder – Parteivorsitzender seit 19.01.2019 ** Die Ehrenvorsitzenden der CSU (Stand: Januar 2019) Josef Müller –Ernennung zum Ehrenvorsitzenden am 13.06.1969 Hans Ehard –Ernennung zum Ehrenvorsitzenden am 13.06.1969 Edmund Stoiber – Ernennung zum Ehrenvorsitzenden am 29.09.2007 Theo Waigel – Ernennung zum Ehrenvorsitzenden am 18.07.2009 Horst Seehofer – Ernennung zum Ehrenvorsitzenden am 14.01.2019 * Die Bezeichnung Landesvorsitzender (seit 1945) wurde 1968 in Parteivorsitzender geändert. ** Die Ernennung zu Ehrenvorsitzenden erfolgte jeweils durch die CSU-Parteitage. Franz Josef Strauß machte in der Präsidiumssitzung am 13.06.1969 darauf aufmerksam, dass die ehemaligen Parteivorsitzenden nach einer Satzungsänderung nicht mehr Mitglied des Landesvorstands wären, stattdessen könnten nun Ehrenmitglieder und Ehrenvorsitzende ernannt werden. 2 Josef Müller – CSU-Parteivorsitzender 1945-1949 (Foto: ACSP) 27.03.1898 in Steinwiesen geboren 1916-1918 Soldat beim Bayerischen Minenwerfer-Bataillon IX 1919-1923 Studium der Rechtswissenschaften -

Wandel Öffentlich-Rechtlicher Institutionen Im Kontext Historisch

D -369- V. Von der Wiedervereinigung bis zur Gegenwart 5.1 Maueröffnung und Programmleistung des SFB Noch am 29. Dezember 1988 antworteten bei einer Passantenumfrage der Abendschau die meisten Befragten, daß sie trotz Gorbatschows Glasnost- Politik nicht erwarten würden, daß die Mauer in absehbarer Zeit fallen würde. Dennoch war ein weiteres Zeichen für die wirtschaftlichen Schwierigkeiten des DDR-Systems die Abschaffung des Zwangsumtauschs Ende Januar 1989 und die damit verbundene Forderung nach einer Änderung des Wechselkurses für die Ost-Mark. In der Westberliner Parteienlandschaft gab es eine Annäherung: am 12. Januar berichtete die Abendschau über ein Koalitionsangebot der Alternativen Liste an die SPD. Als Gemeinsamkeiten stellte die AL die Einführung der Umweltkarte, Tempo 30 in der Innenstadt und den Flächennutzungsplan heraus. Der Regierende Bürgermeister Walter Momper wiegelte jedoch gegenüber SFB-Reporterin Colmar ab; man habe das Ziel, ein Wahlergebnis zu erreichen, das der SPD ein alleiniges Mandat zum Regieren gebe. De facto hatte er schon die Möglichkeit einer Großen Koalition ins Auge gefaßt, war aber innerhalb seiner Partei nicht auf Gegenliebe für diese Option gestoßen. Aus der Wahl am 29.Januar ging die SPD als deutliche Siegerin hervor. Die CDU wurde für den Skandal um den Charlottenburger Baustadtrat Antes abgestraft und erlitt schwere Verluste. Die SPD konnte allerdings nicht allein regieren und war auf die Bildung einer Koalition angewiesen. Am 17. Februar nahm Harald Wolf (Alternative Liste) auf einer Pressekonferenz der Essential-Kommission Stellung zu einer möglichen Koalition. Nachdem die Kommission das staatliche Gewaltmonopol und die Übernahme der Bundesgesetze akzeptiert hatte, erklärte Wolf eine D -370- “praktikable Übereinstimmung” mit der SPD.