Bulletin of the Institute for Western Affairs, Ed. 25

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Jens Spahn), Ralph Brinkhaus

Sondierungsgruppen Finanzen/Steuern CDU: Peter Altmaier (Jens Spahn), Ralph Brinkhaus CSU: Markus Söder, Hans Michelbach SPD: Olaf Scholz, Carsten Schneider Wirtschaft/Verkehr/Infrastruktur/Digitalisierung I/Bürokratie CDU: Thomas Strobl, Carsten Linnemann CSU: Alexander Dobrindt, Ilse Aigner, Peter Ramsauer SPD: Thorsten Schäfer-Gümbel, Anke Rehlinger, Sören Bartol Energie/Klimaschutz/Umwelt CDU: Armin Laschet, Thomas Bareiß CSU: Thomas Kreuzer, Georg Nüßlein, Ilse Aigner SPD: Stephan Weil, Matthias Miersch Landwirtschaft/Verbraucherschutz CDU: Julia Klöckner, Gitta Connemann CSU: Christian Schmidt, Helmut Brunner SPD: Anke Rehlinger, Rita Hagel Bildung/Forschung CDU: Helge Braun, Michael Kretschmer CSU: Stefan Müller, Ludwig Spaenle SPD: Manuela Schwesig, Hubertus Heil Arbeitsmarkt/Arbeitsrecht/Digitalisierung II CDU: Helge Braun, Karl-Josef Laumann CSU: Stefan Müller, Emilia Müller SPD: Andrea Nahles, Malu Dreyer Familie/Frauen/Kinder/Jugend CDU: Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, Nadine Schön CSU: Angelika Niebler, Paul Lehrieder SPD: Manuela Schwesig, Katja Mast Soziales/Rente/Gesundheit/Pflege CDU: Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, Hermann Gröhe, Sabine Weiss CSU: Barbara Stamm, Melanie Huml, Stephan Stracke SPD: Malu Dreyer, Andrea Nahles, Karl Lauterbach Migration/Integration CDU: Volker Bouffier, Thomas de Maizière CSU: Joachim Herrmann, Andreas Scheuer SPD: Ralf Stegner, Boris Pistorius Innen/Recht CDU: Thomas Strobl, Thomas de Maizière CSU: Joachim Herrmann, Stephan Mayer SPD: Ralf Stegner, Eva Högl Kommunen/Wohnungsbau/Mieten/ländlicher -

Brief Aus Berlin

Wird diese Nachricht nicht richtig dargestellt, klicken Sie bitte hier. Brief aus Berlin Nr. 15 | 28.09.2018 Grüß Gott, die CDU/CSU-Bundestagsfraktion hat diese Woche Ralph Brinkhaus (CDU) zu ihrem neuen Vorsitzenden gewählt. Er folgt damit Volker Kauder, der 13 Jahre an der Spitze der Fraktion stand. Die ländlichen Regionen standen am Mittwoch im Mittelpunkt des Fraktionskongresses Heimat mit Zukunft. Dort unterstrich die Fraktion ihr Bekenntnis zum ländlichen Raum und würdigte dessen Rolle für Deutschland. Die CSU im Bundestag wurde durch ihren Vorsitzenden, Alexander Dobrindt, vertreten. Auf dem Wohngipfel im Kanzleramt am 21. September wurde ein Maßnahmenpaket im Umfang von 13 Milliarden Euro verabschiedet. Am Mittwoch debattierte der Bundestag die Ergebnisse in einer Aktuellen Stunde. Horst Seehofer sprach von einem historischen Startschuss. Diese Woche hat der Bundestag zudem über das im Koalitionsvertrag vereinbarte Pflegesofortprogramm beraten. Am Donnerstag wurde im Plenum debattiert wie der Personalengpass in der Pflege verringert und die Versorgungsqualität verbessert werden kann. Viel Spaß beim Lesen! FRAKTIONSVORSITZ Ralph Brinkhaus folgt Volker Kauder Die CDU/CSU-Bundestagsfraktion hat in ihrer Sitzung am Dienstag, den 25. September 2018, Ralph Brinkhaus zu ihrem neuen Vorsitzenden gewählt. Weiterlesen LÄNDLICHER RAUM Starke Regionen Die ländlichen Regionen standen am Mittwoch, den 26. September 2018, im Mittelpunkt des Fraktionskongresses Heimat mit Zukunft. Weiterlesen WOHNRAUMOFFENSIVE Größte Wohnraumoffensive, die es je bei einer Bundesregierung gab Auf dem Wohngipfel im Kanzleramt am 21. September wurde ein Maßnahmenpaket im Umfang von 13 Milliarden Euro verabschiedet. Am Mittwoch debattierte der Bundestag die Ergebnisse in einer Aktuellen Stunde. Weiterlesen PFLEGESOFORTPROGRAMM Für eine bessere Pflege Erstmals hat der Bundestag über das im Koalitionsvertrag vereinbarte Pflegesofortprogramm beraten. -

Bulletin of the GHI Washington Supplement 1 (2004)

Bulletin of the GHI Washington Supplement 1 (2004) Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Stiftung Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. “WASHINGTON AS A PLACE FOR THE GERMAN CAMPAIGN”: THE U.S. GOVERNMENT AND THE CDU/CSU OPPOSITION, 1969–1972 Bernd Schaefer I. In October 1969, Bonn’s Christian Democrat-led “grand coalition” was replaced by an alliance of Social Democrats (SPD) and Free Democrats (FDP) led by Chancellor Willy Brandt that held a sixteen-seat majority in the West German parliament. Not only were the leaders of the CDU caught by surprise, but so, too, were many in the U.S. government. Presi- dent Richard Nixon had to take back the premature message of congratu- lations extended to Chancellor Kiesinger early on election night. “The worst tragedy,” Henry Kissinger concluded on June 16, 1971, in a con- versation with Nixon, “is that election in ’69. If this National Party, that extreme right wing party, had got three-tenths of one percent more, the Christian Democrats would be in office now.”1 American administrations and their embassy in Bonn had cultivated a close relationship with the leaders of the governing CDU/CSU for many years. -

Deutscher Bundestag

Deutscher Bundestag 44. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am Freitag, 27.Juni 2014 Endgültiges Ergebnis der Namentlichen Abstimmung Nr. 4 Entschließungsantrag der Abgeordneten Caren Lay, Eva Bulling-Schröter, Dr. Dietmar Bartsch, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. zu der dritten Beratung des Gesetzentwurfs der Bundesregierung Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur grundlegenden Reform des Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetzes und zur Änderung weiterer Bestimmungen des Energiewirtschaftsrechts - Drucksachen 18/1304, 18/1573, 18/1891 und 18/1901 - Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 575 Nicht abgegebene Stimmen: 56 Ja-Stimmen: 109 Nein-Stimmen: 465 Enthaltungen: 1 Ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 27.06.2014 Beginn: 10:58 Ende: 11:01 Seite: 1 Seite: 2 Seite: 2 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Stephan Albani X Katrin Albsteiger X Peter Altmaier X Artur Auernhammer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Julia Bartz X Günter Baumann X Maik Beermann X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Sybille Benning X Dr. Andre Berghegger X Dr. Christoph Bergner X Ute Bertram X Peter Beyer X Steffen Bilger X Clemens Binninger X Peter Bleser X Dr. Maria Böhmer X Wolfgang Bosbach X Norbert Brackmann X Klaus Brähmig X Michael Brand X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Helmut Brandt X Dr. Ralf Brauksiepe X Dr. Helge Braun X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Cajus Caesar X Gitta Connemann X Alexandra Dinges-Dierig X Alexander Dobrindt X Michael Donth X Thomas Dörflinger X Marie-Luise Dött X Hansjörg Durz X Jutta Eckenbach X Dr. Bernd Fabritius X Hermann Färber X Uwe Feiler X Dr. Thomas Feist X Enak Ferlemann X Ingrid Fischbach X Dirk Fischer (Hamburg) X Axel E. -

Plenarprotokoll 15/56

Plenarprotokoll 15/56 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 56. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 3. Juli 2003 Inhalt: Begrüßung des Marschall des Sejm der Repu- rung als Brücke in die Steuerehr- blik Polen, Herrn Marek Borowski . 4621 C lichkeit (Drucksache 15/470) . 4583 A Begrüßung des Mitgliedes der Europäischen Kommission, Herrn Günter Verheugen . 4621 D in Verbindung mit Begrüßung des neuen Abgeordneten Michael Kauch . 4581 A Benennung des Abgeordneten Rainder Tagesordnungspunkt 19: Steenblock als stellvertretendes Mitglied im a) Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Michael Programmbeirat für die Sonderpostwert- Meister, Friedrich Merz, weiterer Ab- zeichen . 4581 B geordneter und der Fraktion der CDU/ Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisung . 4582 D CSU: Steuern: Niedriger – Einfa- cher – Gerechter Erweiterung der Tagesordnung . 4581 B (Drucksache 15/1231) . 4583 A b) Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Hermann Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 1: Otto Solms, Dr. Andreas Pinkwart, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion Abgabe einer Erklärung durch den Bun- der FDP: Steuersenkung vorziehen deskanzler: Deutschland bewegt sich – (Drucksache 15/1221) . 4583 B mehr Dynamik für Wachstum und Be- schäftigung 4583 A Gerhard Schröder, Bundeskanzler . 4583 C Dr. Angela Merkel CDU/CSU . 4587 D in Verbindung mit Franz Müntefering SPD . 4592 D Dr. Guido Westerwelle FDP . 4596 D Tagesordnungspunkt 7: Krista Sager BÜNDNIS 90/ a) Erste Beratung des von den Fraktionen DIE GRÜNEN . 4600 A der SPD und des BÜNDNISSES 90/ DIE GRÜNEN eingebrachten Ent- Dr. Guido Westerwelle FDP . 4603 B wurfs eines Gesetzes zur Förderung Krista Sager BÜNDNIS 90/ der Steuerehrlichkeit DIE GRÜNEN . 4603 C (Drucksache 15/1309) . 4583 A Michael Glos CDU/CSU . 4603 D b) Erste Beratung des von den Abgeord- neten Dr. Hermann Otto Solms, Hubertus Heil SPD . -

Der Imagewandel Von Helmut Kohl, Gerhard Schröder Und Angela Merkel Vom Kanzlerkandidaten Zum Kanzler - Ein Schauspiel in Zwei Akten

Forschungsgsgruppe Deutschland Februar 2008 Working Paper Sybille Klormann, Britta Udelhoven Der Imagewandel von Helmut Kohl, Gerhard Schröder und Angela Merkel Vom Kanzlerkandidaten zum Kanzler - Ein Schauspiel in zwei Akten Inszenierung und Management von Machtwechseln in Deutschland 02/2008 Diese Veröffentlichung entstand im Rahmen eines Lehrforschungsprojektes des Geschwister-Scholl-Instituts für Politische Wissenschaft unter Leitung von Dr. Manuela Glaab, Forschungsgruppe Deutschland am Centrum für angewandte Politikforschung. Weitere Informationen unter: www.forschungsgruppe-deutschland.de Inhaltsverzeichnis: 1. Die Bedeutung und Bewertung von Politiker – Images 3 2. Helmut Kohl: „Ich werde einmal der erste Mann in diesem Lande!“ 7 2.1 Gut Ding will Weile haben. Der „Lange“ Weg ins Kanzleramt 7 2.2 Groß und stolz: Ein Pfälzer erschüttert die Bonner Bühne 11 2.3 Der richtige Mann zur richtigen Zeit: Der Mann der deutschen Mitte 13 2.4 Der Bauherr der Macht 14 2.5 Kohl: Keine Richtung, keine Linie, keine Kompetenz 16 3. Gerhard Schröder: „Ich will hier rein!“ 18 3.1 „Hoppla, jetzt komm ich!“ Schröders Weg ins Bundeskanzleramt 18 3.2 „Wetten ... dass?“ – Regieren macht Spass 22 3.3 Robin Hood oder Genosse der Bosse? Wofür steht Schröder? 24 3.4 Wo ist Schröder? Vom „Gernekanzler“ zum „Chaoskanzler“ 26 3.5 Von Saumagen, Viel-Sagen und Reformvorhaben 28 4. Angela Merkel: „Ich will Deutschland dienen.“ 29 4.1 Fremd, unscheinbar und unterschätzt – Merkels leiser Aufstieg 29 4.2 Die drei P’s der Merkel: Physikerin, Politikerin und doch Phantom 33 4.3 Zwischen Darwin und Deutschland, Kanzleramt und Küche 35 4.4 „Angela Bangbüx“ : Versetzung akut gefährdet 37 4.5 Brutto: Aus einem Guss – Netto: Zuckerguss 39 5. -

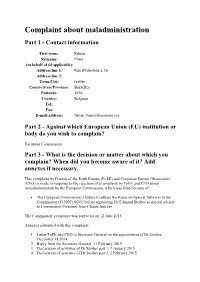

Complaint About Maladministration Part 1 - Contact Information

Complaint about maladministration Part 1 - Contact information First name: Fabian Surname: Flues On behalf of (if applicable): Address line 1: Rue d'Edimbourg 26 Address line 2: Town/City: Ixelles County/State/Province: Bruxelles Postcode: 1050 Country: Belgium Tel.: Fax: E-mail address: [email protected] Part 2 - Against which European Union (EU) institution or body do you wish to complain? European Commission Part 3 - What is the decision or matter about which you complain? When did you become aware of it? Add annexes if necessary. This complaint by Friends of the Earth Europe (FoEE) and Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO) is made in response to the rejection of a complaint by FoEE and CEO about maladministration by the European Commission, which was filed because of: The European Commission’s failure to adhere the Rules on Special Advisers to the Commission (C(2007) 6655) before appointing Dr Edmund Stoiber as special adviser to Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker The Commission’s response was sent to us on 12 June 2015. Annexes submitted with this complaint: 1. Letter FoEE and CEO to Secretary General on the appointment of Dr Stoiber, December 18 2014 2. Reply from the Secretary General, 11 February 2015 3. Declaration of activities of Dr Stoiber part 1, 7 January 2015 4. Declaration of activities of Dr Stoiber part 2, 2 February 2015 5. Declaration of honour of Dr Stoiber 7 January 2015 6. Response Secretary General to FoEE and CEO questions, 16 February 2015 7. Letter FoEE and CEO to Secretary General requesting reconsideration, 25 May 2015 8. -

Winfried Kretschmann – Grüne Bodenhaftung Schmunzelt Sich Ins Schwarz-Gelbe Revier … Lambertz Kalender 2018 „LIFE IS a DANCE“

Ausgabe 14 Journal 11. Jahrgang · Session 2018 2018 Der Zentis Kinder karne- vals preis geht 2018 gleich an zwei Vereine für ihre tolle Nachwuchsarbeit 55 Objekte erzählen A achens Geschichte: Neu erschienenes Buch der Sammlung Crous Mitreißend: Prinz Mike I. und sein Hofstaat bieten anrühren des Prinzenspiel Unser 69. Ritter WIDER DEN TIERISCHEN ERNST: Winfried Kretschmann – grüne Bodenhaftung schmunzelt sich ins schwarz-gelbe Revier … Lambertz Kalender 2018 „LIFE IS A DANCE“ www.lambertz.de Editorial Journal 14 | 2018 3 Liebe Freunde des Öcher Fastelovvends und des , Neben einem großartigen Sessions tischen Bühne hier beim Tierischen auftakt am 11.11.2017 in den Casino Ernst h aben wird. Als ehemaliger Räumen der AachenMünchener er Öcher Prinz und AKV Präsident hat lebte der neue Aachener Prinz Mike I. unser Verein ihm viel zu verdanken. gemeinsam mit seinem Hof staat und Wir danken für die Jahre, in denen er einem restlos begeisterten Publi die Verkörperung des Lennet Kann auf kum eine ebenso grandiose Prinzen den Aachener Bühnen war. pro klamatio n, die wiederum über f acebook und – ganz neu – auch über Abschied genommen haben wir im YouTube live übertragen wurde. Die letzten Jahr unter anderem von unse positive Resonanz hat uns begeistert. rem langjährigen Ordenskanzler Danke hierfür an alle Sponsoren und C onstantin Freiherr Heereman von Unterstützer des AKV! Zuydtwyck, unserem Ritter Heiner Geißler und unserem Senator Karl Freuen können wir uns auch auf un Schumacher. Wir halten sie und alle seren neuen Ritter 2018. Winfried anderen in bleibender Erinnerung Kretschmann ist ein völlig atypischer und gedenken ihrer auch durch un Politiker: ein Grüner, der seinen Daim ser sozia les Engagement, getreu dem ler liebt, ein aufrechter Pazifist, der Motto: „Durch Frohsinn zur Wohltä Das Wahljahr 2017 war vorüber und Mitglied im örtlichen Schützenver tigkeit“. -

1 Introduction

Notes 1 Introduction 1. What belongs together will now grow together (JK). 2. The well-known statement from Brandt is often wrongly attributed to the speech he gave one day after the fall of the Berlin Wall at the West Berlin City Hall, Rathaus Schöneberg. This error is understandable since it was added later to the publicized version of the speech with the consent of Brandt himself (Rother, 2001, p. 43). By that time it was already a well known phrase since it featured prominently on a SPD poster with a picture of Brandt in front of the partying masses at the Berlin Wall. The original statement was made by Brandt during a radio interview on 10 November for SFP-Mittagecho where he stated: ‘Jetzt sind wir in einer Situation, in der wieder zusammenwächst, was zusammengehört’ (‘Now we are in a situation in which again will grow together what belongs together’). 3. The Treaty of Prague with Czechoslovakia, signed 11 December 1973, finalized the Eastern Treaties. 4. By doing this, I aim to contribute to both theory formation concerning inter- national politics and foreign policy and add to the historiography of the German question and reunification policy. Not only is it important to com- pare theoretical assumptions against empirical data, by making the theoretical assumptions that guide the historical research explicit, other scholars are enabled to better judge the quality of the research. In the words of King et al. (1994, p. 8): ‘If the method and logic of a researcher’s observations and infer- ences are left implicit, the scholarly community has no way of judging the validity of what was done.’ This does not mean that the historical research itself only serves theory formation. -

Stunde Null: the End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago." Their Contributions Are Presented in This Booklet

STUNDE NULL: The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago Occasional Paper No. 20 Edited by Geoffrey J. Giles GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE WASHINGTON, D.C. STUNDE NULL The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago Edited by Geoffrey J. Giles Occasional Paper No. 20 Series editors: Detlef Junker Petra Marquardt-Bigman Janine S. Micunek © 1997. All rights reserved. GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1607 New Hampshire Ave., NW Washington, DC 20009 Tel. (202) 387–3355 Contents Introduction 5 Geoffrey J. Giles 1945 and the Continuities of German History: 9 Reflections on Memory, Historiography, and Politics Konrad H. Jarausch Stunde Null in German Politics? 25 Confessional Culture, Realpolitik, and the Organization of Christian Democracy Maria D. Mitchell American Sociology and German 39 Re-education after World War II Uta Gerhardt German Literature, Year Zero: 59 Writers and Politics, 1945–1953 Stephen Brockmann Stunde Null der Frauen? 75 Renegotiating Women‘s Place in Postwar Germany Maria Höhn The New City: German Urban 89 Planning and the Zero Hour Jeffry M. Diefendorf Stunde Null at the Ground Level: 105 1945 as a Social and Political Ausgangspunkt in Three Cities in the U.S. Zone of Occupation Rebecca Boehling Introduction Half a century after the collapse of National Socialism, many historians are now taking stock of the difficult transition that faced Germans in 1945. The Friends of the German Historical Institute in Washington chose that momentous year as the focus of their 1995 annual symposium, assembling a number of scholars to discuss the topic "Stunde Null: The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago." Their contributions are presented in this booklet. -

Germany's Flirtation with Anti-Capitalist Populism

THE MAGAZINE OF INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC POLICY 888 16th Street, N.W. Suite 740 Washington, D.C. 20006 Phone: 202-861-0791 Blinking Fax: 202-861-0790 Left, www.international-economy.com Driving Right B Y K LAUS C. ENGELEN ecent rhetorical attacks against interna- tional corporate investors from the top echelons of Germany’s governing Social Democratic Party, coupled with the crashing defeat of the Red-Green coalition in the latest state elections and the German chancellor’s unexpected move to call a national election a year Germany’s flirtation with earlier than scheduled—all these developments can be seen as Rpart of an “end game” for Gerhard Schröder and the Red-Green coalition. anti-capitalist populism. In a major speech on the future SPD agenda at the party headquarters on April 13, party chairman Franz Müntefering zoomed in on “international profit-maximization strategies,” “the increasing power of capital,”and moves toward “pure cap- italism.” Encouraged by the favorable response his anti-capi- talistic rhetoric produced among party followers and confronted with ever more alarming polls from the Ruhr, he escalated the war of words. “Some financial investors spare no thought for the people whose jobs they destroy,” he told the tabloid Bild. “They remain anonymous, have no face, fall like a plague of locusts over our companies, devour everything, then fly on to the next one.” When a so-called “locust list” of financial investors leaked from the SPD headquarters to the press, the “droning buzz” of Klaus C. Engelen is a contributing editor for both Handelsblatt and TIE. -

Europe's Year Zero After Merkel

PREDICTIONS 2021 171 Europe’s year zero after Merkel Christian Odendahl The German election in September 2021 marks a new beginning in European politics. Angela Merkel, Europe’s most infl uential leader – by size of her country, her experience and skill – will leave the stage for good, leaving a hole to be fi lled. The Christian Democrats (CDU) have de- cided, for now, that Armin Laschet, the prime minister of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany’s biggest state, should follow her as party leader. However, his low popularity among voters will limit the CDU’s overall appeal. Moreover, his inner-party rival, the conservative Friedrich Merz, was able to secure almost half the vote. That shows a deep split in the CDU on the future course, which the party will struggle to contain. On current polls, the outcome of this year’s federal election is fairly obvious: a coalition of the CDU with the Greens enjoys the broadest popular support. The Greens and their emi- nently sensible and measured leadership are keen to be part of the next government, and the CDU always wants to govern – one could go as far as to say that this is the sole purpose of the CDU and its Bavarian sister-party the CSU: to govern, so that the others can’t. But current polls have three fl aws. First, they do not abstract from Merkel. Voters will strug- gle for some time to separate the CDU from her when asked which party they prefer. Second, the Covid-19 pandemic has catapulted the CDU back to almost 40 per cent, for its calm and reasonable (albeit far from perfect) leadership during this crisis.