Lifelong Discovery Handelseditie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Louis-Marie Fardet - Artist Bio and CV

Louis-Marie Fardet - Artist Bio and CV Born in Rochefort, France and then Parisian since the 90’s to attend a special unique high-school (Lycée Racine) for pre-professional level musicians (1990-93), Louis-Marie got accepted at the prestigious Paris Conservatory in 1992 in Philippe Muller’s Studio and graduated in 1996. L-M studied the following 2 years with Michel Strauss in “Perfectionnement” cello class. Louis-Marie continued his studies pursuing a Master for 2 years at Rice University (1999-2001) Then he came back to France in 2001 and became a tenured member of the prestigious Paris Opera Orchestra in 2002, 6 months only after winning the audition on a 10/10 Commitee vote. After a 5 years tenure in Opéra de Paris, Louis-Marie moved back in late 2006 to Houston, Texas and served as Assistant Principal Cellist for the Houston Grand Opera and Ballet until 2015, year he won the 4th chair position with the Houston Symphony. As part of his contract L-M has been acting principal cellist for the Houston Symphony Orchestra a couple weeks a year Teaching Experience: Louis-Marie is now an Aeyons faculty since May 2020. Louis-Marie has held a small private studio at home and helped numerous students from Middle school and High School to help them through all their school orchestra repertoire and All State & Region orchestra auditions. L-M has given numerous cello & ensemble lessons & Masterclasses at Sam Houston State University during the last 14 years he’s established in Texas. L-M is also a core cello faculty at the annual Texas summer String Camp. -

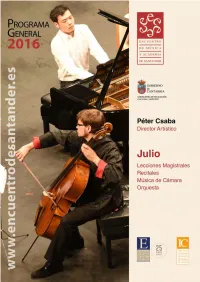

Programa2016.Pdf

l Encuentro de Música y Academia cumple un año más el reto de superarse a sí mismo. La programación de 2016 combina a la perfección la academia, la experiencia y el virtuosismo de los más grandes, como el maestro Krzysztof Penderecki, con la frescura, las ganas y el entusiasmo de los jóvenes músicos Eparticipantes en esta cita ineludible cada verano en Cantabria. Más de 50 conciertos en los escenarios del Palacio de Festivales de Cantabria, en el Palacio de La Magdalena y en otras 22 localidades acercarán la Música con mayúsculas a todos los rincones de la Comunidad Autónoma para satisfacer a un público exigente y siempre ávido de manifestaciones culturales. Para esta tierra, es un privilegio la oportunidad de engrandecer su calendario cultural con un evento de tanta relevancia nacional e internacional. Así pues, animo a todos los cántabros y a quienes nos visitan en estas fechas estivales a disfrutar al máximo de los grandes de la música y a aportar con su presencia la excelente programación que, un verano más, nos ofrece el Encuentro de Música y Academia. Miguel Ángel Revilla Presidente del Gobierno de Cantabria esde hace ya 16 años, el Encuentro de Música y Academia de Santander sigue fielmente las líneas maestras que lo han convertido en un elemento muy prestigioso del verano musical europeo. En Santander —que es una delicia en el mes de julio— se reúnen jóvenes músicos seleccionados uno a uno mediante audición en las escuelas de mayor prestigio Dde Europa, incluida, naturalmente, la Reina Sofía de Madrid. Comparten clases magistrales, ensayos y conciertos con una serie igualmente extraordinaria de profesores, los más destacados de cada instrumento en el panorama internacional. -

Sirba-Tantz-Ang-Eng-2017-Site.Pdf

S I R B A O C T E T Tantz ! Sirba Octet www.sirbaoctet.com © © Bernard Martine “Tantz! has its roots in the Eastern IT IS A PORTRAIT OF LIFE ITSELF! Europe of my grandparents before they emigrated nearly 100 years “It is a portrait of life itself – a lifetime T A N ago. I wanted to rediscover this of love that no longer exists to which intrinsic element of my cultural song is the only possible testimony we orientation by revisiting this music as the classical musician I am can have in the end. It encapsulates a TZ today.” whole era which used to exist and isn’t there any more but which will live on in Inspired by the migration both of the souls of those who value it and we people and of their music, the must all value it because it comes ! show forms a kind of bridge directly from the heart. between Romania, Moldova, Russia and Hungary and their That is what it is. rich, interwoven treasuries of traditional folk music. Each We must thank these wonderful carefully selected piece retains the musicians who have come together to identity and authenticity which we share and sustain this symbol of love, must protect and pass on, like Ariadne’s thread, thereby continuing the musical heritage reanimating a forgotten time that is that is an ode to life – moving, joyful and tinged with humour. ever present. Richard Schmoucler, artistic Thank you!” director (translated from original French) Ivry Gitlis, Paris, September 30th 2014 (translated from the original French) AN ENERGETIC AND HEARTFELT MUSICAL JOURNEY Tantz! means dance in Yiddish and this title eludes to the emotion, elegance and vigour of the show itself. -

Chamber Music & Music for Piano Solo

VIVIERCHAMBER MUSIC & MUSIC FOR PIANO SOLO Alessandro Soccorsi piano Thies Roorda flute Joseph Puglia violin Sietse-Jan Weijenberg cello Niels Meliefste percussion Pepe Garcia percussion Claude Vivier 1948-1983 Immediately after his birth, Claude Vivier (Montreal, 14 April 1948 – Paris, 7 March Chamber Music & Music for Piano Solo 1983) was taken to an orphanage. His mother abandoned the young boy simply because at the time, in Roman Catholic Quebec, society would not accept illegitimate 1. Shiraz for piano solo (1977) 14’44 4. Pianoforte for piano solo children. When Armand and Jeanne Vivier visited the orphanage in December 1950, Salabert, Paris (1975) 8’03 they were initially in search of a girl. They decided to adopt the little Claude instead. 1985, Les Éditions YPPAN, These events would mark his further life and art. 2. Pulau Dewata Saint-Nicolas, Canada From his 13th birthday onwards, he attended a few schools with the aim of for variable ensemble (1977) 13’03 becoming a Catholic frère. Some five years later, the seminary advised him to Arr. for piano and percussion 5. Paramirabo for flute, violin, withdraw. “Community life with rules: he wasn’t cut out for that.” His search for by A. Soccorsi cello and piano (1978) 14’23 “life,” as he himself wrote, “in the most creative and universal sense of the term,” 1988, Les Éditions YPPAN, as well as his emerging homosexuality, may have been decisive reasons. His true 3. Pièce for cello and piano Saint-Nicolas, Canada vocation turned out to be music. He enrolled at the Conservatoire de musique in (1975) 6’52 Montreal in 1967. -

Cello Biennale 2018

programmaoverzicht Cellists Harald Austbø Quartet Naoko Sonoda Nicolas Altstaedt Jörg Brinkmann Trio Tineke Steenbrink Monique Bartels Kamancello Sven Arne Tepl Thu 18 Fri 19 Sat 20 Sun 21 Mon 22 Tue 23 Wed 24 Thu 25 Fri 26 Sat 27 Ashley Bathgate Maarten Vos Willem Vermandere 10.00-16.00 Grote Zaal 10.00-12.30 Grote Zaal 09.30 Grote Zaal 09.30 Grote Zaal 09.30 Grote Zaal 09.30 Grote Zaal 09.30 Grote Zaal 09.30 Grote Zaal Kristina Blaumane Maya Beiser Micha Wertheim First Round First Round (continued) Bach&Breakfast Bach&Breakfast Bach&Breakfast Bach&Breakfast Bach&Breakfast Bach&Breakfast Arnau Tomàs Matt Haimovitz Kian Soltani Jordi Savall Sietse-Jan Weijenberg Harriet Krijgh Lidy Blijdorp Mela Marie Spaemann Santiago Cañón NES Orchestras and Ensembles 10.15-12.30 10.15-12.30 10.30-12.45 Grote Zaal 10.15-12.30 10.15-12.30 10.15-12.30 10.15-12.30 10.30 and 12.00 Kleine Zaal Master class Master class Second Round Masterclass Masterclass Masterclass Masterclass Valencia Svante Henryson Accademia Nazionale di Santa Show for young children: Colin Carr (Bimhuis) Jordi Savall (Bimhuis) Jean-Guihen Queyras Nicolas Altstaedt (Bimhuis) Roel Dieltiens (Bimhuis) Matt Haimovitz (Bimhuis) Colin Carr Quartet Cecilia Spruce and Ebony Jakob Koranyi (Kleine Zaal) Giovanni Sollima (Kleine (Bimhuis) Michel Strauss (Kleine Zaal) Chu Yi-Bing (Kleine Zaal) Reinhard Latzko (Kleine Zaal) Zaal) Kian Soltani (Kleine Zaal) Hayoung Choi The Eric Longsworth Amsterdam Sinfonietta 11.00 Kleine Zaal Chu Yi-Bing Project Antwerp Symphony Orchestra Show for young children: -

Takacs Quartet

2020-21 Season Digital program Contents Click on an item to navigate to its page. Pandemic Players: A Peek Behind the Masks Performance program CU Presents Digital Your support matters CU Presents personnel is the home of performing arts at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Grammy Award-winning Takács Quartet has been moving audiences and selling out concerts for three decades at CU Boulder. As we gather, we honor and acknowledge that the University of Colorado’s four campuses are on the traditional territories and ancestral homelands of the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Ute, Apache, Comanche, Kiowa, Lakota, Pueblo and Shoshone Nations. Further, we acknowledge the 48 contemporary tribal nations historically tied to the lands that comprise what is now called Colorado. Acknowledging that we live in the homelands of Indigenous peoples recognizes the original stewards of these lands and their legacies. With this land acknowledgment, we celebrate the many contributions of Native peoples to the fields of medicine, mathematics, government and military service, arts, literature, engineering and more. We also recognize the sophisticated and intricate knowledge systems Indigenous peoples have developed in relationship to their lands. We recognize and affirm the ties these nations have to their traditional homelands and the many Indigenous people who thrive in this place, alive and strong. We also acknowledge the painful history of ill treatment and forced removal that has had a profoundly negative impact on Native nations. We respect the many diverse Indigenous peoples still connected to this land. We honor them and thank the Indigenous ancestors of this place. The University of Colorado pledges to provide educational opportunities for Native students, faculty and staff and advance our mission to understand the history and contemporary lives of Native peoples. -

IVRY GITLIS MICHEL STRAUSS Violon Violoncelle

Création de l’Académie Internationale de Musique de Cassis en 2017 sous le nom de Ivry Gitlis. Le but de cette association est de promouvoir à Cassis la musique classique de façon pérenne. IVRY GITLIS MICHEL STRAUSS Violon Violoncelle Ces deux grands professeurs veulent pour inaugurer cette académie de musique organiser un événement musical exceptionnel de très haute qualité́. Cet événement musical se déroulera à l'Oustau Calendal à Cassis du 21 au 26 octobre prochain. Les professeurs recevront 18 jeunes musiciens, déjà lauréats de nombreux concours, issus des structures les plus prestigieuses en France et à l'étranger (Belgique, Canada, Corée, USA…). Les cours donnés par Ivry Gitlis et Michel Strauss à ces jeunes talents auront lieu à l’Oustau Calendal du dimanche 22 octobre au jeudi 26 octobre. Les élèves et leurs professeurs seront accompagnés au piano par Evelina Pitti et Frédéric Isoletto. Deux concerts de clôture de ces masterclasses seront organisés le jeudi 26 Octobre à l’Oustaou Calendal par les élèves et leurs professeurs : - le premier à 17 h 30 - le second à 21 h Il est d’ores et déjà possible de réserver les places par téléphone au 0661506279 ou de les acheter en arrivant à L’Oustaou le jeudi 26 octobre. Tarifs : - 20 euros un concert - 30 euros les deux concerts - 5 euros pour les enfants de moins de 12 ans AIMC Page 1 / 3 IVRY GITLIS Initié au violon à l’âge de six ans, il donne son premier concert à peine un an après. Encouragé par le musicien Bronislaw Huberman, Ivry Gitlis part pour l’Europe. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Interpreting

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Interpreting Henri Dutilleux’s Quotations of Baudelaire in Tout un monde lointain… A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts by Charles Robert Tyler 2016 © Copyright by Charles Robert Tyler 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Interpreting Henri Dutilleux’s Quotations of Baudelaire in Tout un monde lointain… by Charles Robert Tyler Doctor of Musical Arts University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Antonio Lysy, Chair Henri Dutilleux (1916-2013) is one of the most significant and widely acclaimed composers of the last century. Dutilleux is best known for his approach towards orchestral timbre and color and his works exhibit an individual style that defies classification. This dissertation will be dedicated to exploring the interpretive issues presented in Henri Dutilleux’s composition for cello and orchestra, Tout un monde lointain… The quotations taken from Baudelaire’s poetry found in this score above each movement leave the performer with many unanswered interpretive questions. Through researching Dutilleux’s use of quotation in other scores, examining the intricacies of Baudelaire’s poetry and considering the existing publications pertaining to his concerto, one will be considerably better equipped to answer the varying questions sense of mystery raised by these quotations. Such analysis will aid one in interpreting and executing his concerto with a heightened understanding of Dutilleux’s musical language within the aesthetics and context he provides through his quotations of Baudelaire. ! ii! This dissertation of Charles Robert Tyler is approved. Mark C. Carlson Laure Murat Guillaume Bruno Sutre Antonio Lysy, Committee Chair University of California, Los Angeles 2016 ! iii! To my parents Robert and Katharine Tyler for their endless support and encouragement, and to Eric, without whom I would not be where I am today. -

Sirba-Dossiers-Yiddish-Rhapsody-2016-Bat-Ilovepdf-Compressed1.Pdf

S I R B A O C T E T ©Alix Laveau Yiddish Rhapsody presents a range FROM DONA DONA TO of music including traditional folk, QUENTIN TARANTINO jazz, bolero, rock and musical YI theatre favourites. By turns poetic, New and original arrangements of tender, touching and funny the Yiddish melodies in a variety of show is an incredible ode to life. styles form the backbone of the show. By turns poetic, tender, D DI YIDDISH IN ALL ITS touching and funny, it is a VARIETY wonderful ode to life. Sirba Octet, orchestra and Isabelle Georges Yiddish Rhapsody presents an perform at times separately at H eclectic, original and celebratory times as a full ensemble creating mix of instrumental music and balance and contrasting musical songs. Unusually, the Sirba Octet is moods. joined by a full symphony RHA orchestra and Isabelle Georges, a This one-off show offered a major personality of musical unifying and heart-felt range of theatre who sings in Yiddish. music including the inspiring and profound Dona Dona, the PSO In 2009, at the request of the impassioned Misirlou, popularised Orchestre de Pau – Pays de Béarn by Quentin Tarantino in Pulp conducted by Faycal Karoui, Fiction, the nostalgia of Yingele Isabelle George and Richard nit veyn, the Sirtaki version of A D Y Schmoucler created Yiddish Keshenever and energetic Rhapsody to capture the essence of orchestral pieces Yiddish the legendary music cherished by Charleston and Beltz. In Eastern European Jewish combination with the skill and communities. The show was expertise of the Sirba Octet and arranged by Cyrille Lehn. -

![Ensemble]H[Iatus](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4933/ensemble-h-iatus-6264933.webp)

Ensemble]H[Iatus

ensemble]h[iatus Géraldine Keller A multidisciplinary orientated performance practice of Contemporary voice Music is one of the main characteristics of the french-german-italian ensemble]h[iatus, which had been founded in 2006 by the cellist Martine Tiziana Bertoncini Altenburger and the percussionist Lê Quan Ninh. violin The special feature of this ensemble is that all its members are both, interpreters and improvisers. In addition to this duality, they also show a Angelika Sheridan widely spread creative background: in a multifaceted way, all ensemble futes members work in various areas such as composition, electro-acoustic music, computer music, sound art, installation art, performance, theatre, Isabelle Duthoit music theatre, dance, multimedia, etc. clarinet The projects presented by the ensemble refect these artistic orientations Martine Altenburger entirely: instead of simply performing repertory pieces from the 20th and violoncello 21st century, the ensemble]h[iatus creates concert programmes – non- interrupted by breaks or applauses – which embrace performances of Fabrice Charles repertoire or commissioned compositions alternated with improvisations trombone by the ensemble. Realisations of performative, multimedia, text-based or graphic works belong to the spectrum of the collectively developed Carl Ludwig Hübsch work. tuba Another central and ongoing interest of the ensemble is to seek for close collaborations with the composers. Various commissioned works have Thomas Lehn been written for and premiered by the ensemble]h[iatus. piano, analogue synthesizer The frst full CD of the ensemble has been published by the French label Lê Quan Ninh Césaré in February 2017. This release includes three pieces by Austrian percussion composer Peter Jakober and improvisations by the ensemble]h[iatus. -

Sarah Kapustin Violin Roeland Jagers Viola

1 RR EE FF LL SARAH KAPUSTIN VIOLIN EE CC TT II ROELAND JAGERS VIOLA DES PREZ DI LASSO BACH MOZART TOCH MARTINU˚ OO NN SS ROUKENS 2 SARAH KAPUSTIN music with Michel Strauss and Vladimir Mendelssohn. Sarah Kapustin’s musical activities have Currently Sarah resides in Zwolle, the taken her across North and South America, Netherlands, where she is active as a Europe, Asia and Australia. Born in Mil chamber musician, soloist and concert waukee, WI, she has performed as soloist master. She also performs and tours with such orchestras as the Milwaukee regularly with the Orpheus Chamber Or Symphony Orchestra, Juilliard Symphony, ches tra, Amsterdam Sinfonietta and the Pasadena Symphony, Vogtland Philharmonie Chamber Orchestra of Europe. Increasingly and the Pro Arte Orchestra of Hong Kong. sought after as a teacher, she is professor of Sarah has received numerous prizes and violin at the ArtEZ Conservatorium (Zwolle), honors, including 1st prize of the Inter professor of chamber music at the Prins national Instrumental Competition in Claus Conservatorium (Groningen), and in Markneukirchen. She has appeared in such 2017 she joined the faculty of the Sweelinck prestigious concert venues as Carnegie Hall, Academie (preparatory division of the Ams Alice Tully Hall, Cité de la Musique in Paris, ter dam Conservatory). She has given mas the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, Mexico ter classes in the US, the Netherlands, City’s Sala Nezahualcoyotl, Hong Kong France, Belgium, Spain, Brazil, Columbia Cultural Centre, and Capella State Hall in and Hong Kong, and is a faculty member of St.Petersburg. the Indiana University Summer String A devoted and passionate chamber Academy. -

13-17/11 Flagey

FeStiVal a Cambre. l V a NS e DebussyChauSSoNFraNCkFauréSaiNt-SaëNSraVel 13-17/11 Flagey Création graphique: Mathilde Collobert, Mathilde Collobert, graphique: Création Queen elisabeth Music chapel artistic season 2012 - 2013 56 artists in residence 24 nationalities MaiN SpoNSorS Co-SpoNSor 2 1 après Chopin en 2010 et brahms en 2011, la chapelle Musicale reine elisabeth et Flagey, en coproduction sous la présidence d’honneur avec l’orchestre royal philharmonique de liège et le brussels philharmonic, présentent à nouveau ensemble de s.M. la reine un festival d’automne, le Festival ‘a la française’, du 13 au 17 novembre 2012 à Flagey. onder het erevoorzitterschap Ce festival, programmé par la Chapelle Musicale, est dédié à la musique française du ‘tournant de siècle’, une période extrêmement riche que le public peut explorer à travers les plus belles oeuvres des maîtres fran- van h.M. de Koningin çais tels que Claude Debussy, Camille Saint-Saëns, gabriel Fauré, eric Satie, Maurice ravel, César Franck ou encore Francis poulenc. le Festival ‘a la française’ peut compter, et c’est une des caractéristiques de la Chapelle Musicale : le com- pagnonnage, sur la participation de musiciens de réputation internationale comme augustin dumay, Gary hoffman, Jean-philippe collard, abdel rahman el bacha ou encore Gérard caussé, associés notamment aux solistes de la Chapelle. Cinq jours de festival, 12 concerts & plus de cinquante artistes, le chœur octopus et deux orchestres belges seront de la partie : l’orchestre philharmonique royal de liège dirigé par christian arming, ainsi que le brus- sels philharmonic sous la baguette de Michel tabachnik. Devenu une marque de maison pour Flagey, le Festival ‘a la française’ n’est pas exclusivement musical, notons au programme une soirée satie mêlant mélodies et extraits de la correspondance presque complète d’erik Satie.