32 Biographies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voir Le Dépliant De Présentation Du Festival 2019

9e édition les 7, 8 et 9 JUIN 2019 FONTAINEBLEAU Thème LE PEUPLE Pays invités LES PAYS NORDIQUES NOTE À L'ATTENTION DES AMBASSADEURS #FHA19 festivaldelhistoiredelart.com Préprojet de la 9e édition du Festival de l'histoire de l'art 18 janvier 2019 Réalisation Jean-Baptiste Jamin d'après la maquette de Philippe Apeloig Document de travail – merci de ne pas diffuser 4 Pays invités : les pays nordiques 8 Thème : le Peuple 12 Forum de l’Actualité 14 Cinéma 16 Salon du livre et de la revue d’art 18 Visites et spectacles 20 Jeune public 22 Université de printemps 24 Les organisateurs 28 Le comité scientifique 30 Les partenaires 43 Appel au mécénat Festival de l’histoire de l’art 7, 8 et 9 juin 2019 4 Pays invités : les pays nordiques Carte de la Scandinavie, du Groenland, de l'Islande, des îles Féroé, des Orcades et de la Mer Baltique - Portulan, XVIe siècle - Lyon, bibliothèque numérique 5 Chaque année, le Festival invite un pays La programmation dédiée aux pays Ces quelques questionnements à présenter son actualité de l'art, nordiques est en cours d’élaboration par le n’entendent en rien épuiser la thématique. la production artistique qui s'y comité scientifique du Festival, assisté par S'y ajouteront les sujets relatifs aux œuvres developpe, ses avant-gardes, ses un groupe de travail composé de d’art et au patrimoine, à l’histoire de ruptures et ses paradoxes, ainsi que sa spécialistes de chacun des pays invités. l’architecture, de l’urbanisme, à scène artistique contemporaine l’archéologie, à la muséographie, à la C’est également l’occasion de comparer En mettant à l’honneur un territoire danse, au design, à la musique, à la ses méthodes de recherche et composé de cinq pays, il s’agira d’en photographie, au cinéma, voire au théâtre. -

En Staangeld 2021

Nr. 347527 31 december GEMEENTEBLAD 2020 Officiële uitgave van de gemeente Súdwest-Fryslân Verordening op de heffing en invordering van lig – en staangeld 2021 De raad van de gemeente Súdwest-Fryslân; gelezen het voorstel van burgemeester en wethouders d.d. 10 november 2020; gelet op artikel 229 van de Gemeentewet b e s l u i t : vast te stellen de verordening op de heffing en invordering van lig- en staangeld 2021 Artikel 1 Definities In deze verordening wordt verstaan onder: • ½ jaar: een aangesloten tijdvak van zes kalendermaanden; • 7 dagen: een aaneengesloten tijdvak van 7 dagen; • A-locaties: ligplaatsen inclusief stroomvoorziening; • B-locaties: ligplaatsen exclusief stroomvoorziening; • camper: een (bestel)auto, ingericht voor het vervoeren van twee of meer personen en geschikt voor kamperen cq. buitenshuis verblijven met de mogelijkheid tot overnachten; • camperovernachtingsplaats: een door het college aangewezen locatie buiten kampeerterreinen waar campers/kampeerauto’s geplaatst kunnen worden ten behoeve van recreatief nachtverblijf, zijnde een gereguleerde overnachtingsplaats (GOP); • college: college van burgemeester en wethouders van de gemeente Súdwest-Fryslân; • etmaal: een periode van 24 uren, gerekend vanaf 10.00 uur; • historische schepen: schepen die het college als zodanig aanmerkt; • laadvermogen: het in tonnen uitgedrukte verschil tussen de zoetwaterverplaatsing van het schip bij de grootst toegelaten diepgang en die van het ledige schip; • ligplaats: de ruimte die een vaartuig in gebruik neemt; • maand: kalendermaand; • meetbrief: het document als bedoeld in artikel 1.10 van het Binnenvaartpolitiereglement; • nacht: het aaneengesloten tijdvak vanaf 18.00 tot 09.00 uur; • passagiersschip: a. een vaartuig dat is bestemd of wordt gebruikt voor het bedrijfsmatig vervoer van personen; b. -

Louis-Marie Fardet - Artist Bio and CV

Louis-Marie Fardet - Artist Bio and CV Born in Rochefort, France and then Parisian since the 90’s to attend a special unique high-school (Lycée Racine) for pre-professional level musicians (1990-93), Louis-Marie got accepted at the prestigious Paris Conservatory in 1992 in Philippe Muller’s Studio and graduated in 1996. L-M studied the following 2 years with Michel Strauss in “Perfectionnement” cello class. Louis-Marie continued his studies pursuing a Master for 2 years at Rice University (1999-2001) Then he came back to France in 2001 and became a tenured member of the prestigious Paris Opera Orchestra in 2002, 6 months only after winning the audition on a 10/10 Commitee vote. After a 5 years tenure in Opéra de Paris, Louis-Marie moved back in late 2006 to Houston, Texas and served as Assistant Principal Cellist for the Houston Grand Opera and Ballet until 2015, year he won the 4th chair position with the Houston Symphony. As part of his contract L-M has been acting principal cellist for the Houston Symphony Orchestra a couple weeks a year Teaching Experience: Louis-Marie is now an Aeyons faculty since May 2020. Louis-Marie has held a small private studio at home and helped numerous students from Middle school and High School to help them through all their school orchestra repertoire and All State & Region orchestra auditions. L-M has given numerous cello & ensemble lessons & Masterclasses at Sam Houston State University during the last 14 years he’s established in Texas. L-M is also a core cello faculty at the annual Texas summer String Camp. -

Download PDF ( Final Version , 3Mb )

samengesteld door: CC Veldwaarnemingen Nel van Donkersgoed 2 liefst zen, polders ten zuiden van Den Helder, 10-2-96 U gelieve voor deze rubriek, tweemaandelijks, uw IJmuiden Tak, P. de J. van gegevens op te zenden naar onderstaand adres. Onvol- ex. Zuidpier, (P. Droog, alle T. van ledige gegevens worden niet opgenomen. Bij waar- Blanken, Dijk). Ijseend. 30-12-95 1 ex. Scharendijke Z. nemingen naast locatie van waarneming ook de ge- juv. haven, meente vermelden. Informatie over zeldzame en bijzon- (H.C.Ravesteijn), 13-1-96 1 9 en 1 cf Lauwersoog dere waarnemingen (bijvoorbeeld uitzonderlijke data of (J. Mulder), 4-2-96 1 ex. Brouwersdam, Goedereede aantallen), gaarne met uitgebreide omschrijving en zo- (N. Buiten), 7-11-96 1 9 Kennemerplas, IJmuiden met foto’s. Geen dia’s afdrukken van mogelijk inzenden, (M. van de Kwast, A. Schortinghuis). dia’s zijn welkom (formaat 10 x 15, glanzend). Wespendief. 10-9-96 1 ex. ca. 2 weken bij familie A.B. In de ’Lijst van Nederlandse vogels’ van van den Witteveen, Marnedijk, Witmarsum, Zie ook Leeu- Berg & C.A.W. Bosman (zie ’Het Vogeljaar’ 44 (3): 136) warder Courant. De heer E.W.F. Brandenburg was zeldzame treft u een lijst aanvan vogelsoortenwaarvan daar 2 dagen later. Heeft samen met de heer W. uit- een beschrijvingvan de soort is vereist om te worden op- gegraven wespennesten bekeken, maar vogel ving genomen. ook wel muizen, aldus de heer Witteveen (med Vogelsoorten die zijn vermeld op de nationale Rode ** E.W.F. 17-9-96 5 Groote Wielen, Lijst, worden aangeduid met één *, twee betekent dat Brandenburg); ex. -

Programme 2016

71e CONCOURS DE GENÈVE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC COMPETITION PROGRAMME 2016 CONCOURSGENEVE.CH Partenaire principal Croquis du sinistre Quoi qu’il arrive – nous vous aidons rapidement et simplement. mobiliere.ch Agence générale Genève Denis Hostettler Route du Grand-Lancy 6a 1227 Les Acacias T 022 819 05 55 [email protected] SOMMAIRE SUMMARY I. INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION 3 Messages de bienvenue Official messages 3 Comment fonctionne le Jury How the Jury works 10 II. CONCOURS DE CHANT VOICE COMPETITION 11 Programme Programme 12 Prix et récompenses Prizes & awards 15 Candidats Candidates 17 Membres du Jury Jury members 28 Accompagnateurs Accompanists 40 Orchestre et chef Orchestra & conductor 42 III. CONCOURS DE QUATUOR STRING QUARTET À CORDES COMPETITION 45 Programme Programme 46 Prix et récompenses Prizes & awards 48 Candidats Candidates 51 Membres du Jury Jury members 60 Compositeur Composer 71 IV. AUTOUR DU CONCOURS AROUND THE COMPETITION 73 Concert d’ouverture Opening concert 75 Concert vernissage Concert inauguration 76 Pédagogie et médiation Education & mediation 77 V. LAURÉATS PRIZE-WINNERS 85 Programme de soutien Career development programme 86 Coup de Cœur Breguet Coup de Cœur Breguet Prize 89 Tournée des lauréats Laureates tour 91 Festival des lauréats Laureates festival 93 Interview du Quatuor Voce Interview of Quatuor Voce 95 Nouvelles des lauréats News of the laureates 100 VI. SOUTIENS SUPPORTS 107 Amis du concours Friends association 108 Partenaires et soutiens Partners & Supports 111 VII. PRATIQUE PRACTICAL 113 Billetterie, tarifs Tickets, prices 115 Lieux Places 118 Organisation Organization 119 Contacts Contacts 120 — 1 — ALTERNATIVE.CH | CI/UN/CH/F/121215 CI/UN/CH/F/121215 La discipline crée la stabilité. -

Recent Publications in Music 2010

Fontes Artis Musicae, Vol. 57/4 (2010) RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC R1 RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC 2010 Compiled and edited by Geraldine E. Ostrove On behalf of the Pour le compte de Im Auftrag der International l'Association Internationale Internationalen Vereinigung Association of Music des Bibliothèques, Archives der Musikbibliotheken, Libraries Archives and et Centres de Musikarchive und Documentation Centres Documentation Musicaux Musikdokumentationszentren This list contains citations to literature about music in print and other media, emphasizing reference materials and works of research interest that appeared in 2009. It includes titles of new journals, but no journal articles or excerpts from compilations. Reporters who contribute regularly provide citations mainly or only from the year preceding the year this list is published in Fontes Artis Musicae. However, reporters may also submit retrospective lists cumulating publications from up to the previous five years. In the hope that geographic coverage of this list can be expanded, the compiler welcomes inquiries from bibliographers in countries not presently represented. CONTRIBUTORS Austria: Thomas Leibnitz New Zealand: Marilyn Portman Belgium: Johan Eeckeloo Nigeria: Santie De Jongh China, Hong Kong, Taiwan: Katie Lai Russia: Lyudmila Dedyukina Estonia: Katre Rissalu Senegal: Santie De Jongh Finland: Tuomas Tyyri South Africa: Santie De Jongh Germany: Susanne Hein Spain: José Ignacio Cano, Maria José Greece: Alexandros Charkiolakis González Ribot Hungary: Szepesi Zsuzsanna Tanzania: Santie De Jongh Iceland: Bryndis Vilbergsdóttir Turkey: Paul Alister Whitehead, Senem Ireland: Roy Stanley Acar Italy: Federica Biancheri United Kingdom: Rupert Ridgewell Japan: Sekine Toshiko United States: Karen Little, Liza Vick. The Netherlands: Joost van Gemert With thanks for assistance with translations and transcriptions to Kersti Blumenthal, Irina Kirchik, Everett Larsen and Thompson A. -

Download 2018 Catalog

JUNE 23 Bing Concert Hall Joshua Redman Quartet presented by JUNE 22 – AUGUST 4 28 BRILLIANT CONCERTS STANFORDJAZZ.ORG presented by JUNE JULY FRI FRI FRI FRI SAT SAT SAT SAT SAT MON SUN SUN 22 23 SUN 24 29 30 1 6 7 7 13 14 15 16 Indian Jazz Journey JUNE 22 – AUGUST 4 with Jazz on 28 BRILLIANT CONCERTS George the Green: Brooks, Early Bird Miles STANFORDJAZZ.ORG Jazz featuring Jazz for Electric Ruth Davies’ Inside Out Mahesh Dick Kids: An Band, Kev Tommy Somethin’ Blues Night with Joshua Kale and Tiffany Christian Hyman Jim Nadel American Choice, Igoe and Else: A with Special Jim Nadel Redman Bickram Austin McBride’s and Ken and the Songbook Sidewalk the Art of Tribute to Guest Eric & Friends Quartet Ghosh Septet New Jawn Or Bareket Peplowski Zookeepers Celebration Chalk Jazz Cannonball Bibb JULY AUGUST FRI FRI SAT SAT SAT TUE WED THU THU SUN SUN WED WED MON 18 19 21 22 23 25 26 27 28 29 MON 30 31 1 3 4 SJW All-Star Jam Wycliffe Gordon, Melissa Aldana, Taylor Eigsti, Yosvany Terry, Charles McPherson, Jeb Patton, Tupac SJW CD Mantilla, Release Jazz Brazil: Dena Camila SJW CD Regina Party: Anat DeRose Jeb Patton Meza, Release Carter Caroline Cohen/ Terrence Trio with Trio and Yotam party: An & Xavier Davis’ Romero Brewer Anat Yosvany Tupac Silberstein, Debbie Evening Davis: Heart Tonic Lubambo/ Acoustic Cohen and Charles Terry Taylor Mantilla’s Mike Andrea Poryes/ with Duos and Bria and Jessica Vitor Remembering Jazz Jimmy McPherson Afro-Cuban Eigsti Trio Point of Rodriguez, Motis Sam Reider Victor Lin Quartet Skonberg Jones Gonçalves Ndugu Quartet Heath Quintet Sextet and Friends View and others. -

PROGRAM C'd I .:R:F 1=Jj 5D3

PROGRAM C'D I .:r:F 1=Jj 5D3 Piece pour piano et quatuor acordes (1991) ...........':!:!..?:..?::........... Olivier Messiaen (1908·1992) Luke Fitzpatrick, violin Hye Jung Yang, cello Allion Salvador, violin Zack Myers, piano Vijay Chalasani, viola z.. Feuilles atravers les cloches (1998) .................?.~......:c............................ Tristan Murall (b. 1947) Natalie Ham, flute Isabella Kodama, cello Luke Fitzpatrick, violin Steven Damouni, piano 3 Rain Spell (1983) ................................9..;.H.:t..................................... Toru Takemitsu (1930·1996) Natalie Ham, flute Lauren Wessels, harp Ivan Arteaga, clarinet Ania Stachurska, piano Isaac Anderson, vibraphone 4 Les Sept crimes de I'amour (1979) ................. J.?::.: ..f:?..r?.. ................... Georges Aperghis (b. 1945) Sequence I Sequence II Sequence III Sequence IV Sequence V Sequence VI Sequence VII Emerald Lessley, soprano Ivan Arteaga, clarinet Isaac Anderson, percussion INTERMISSION CD2-#l7-1 S'D'1 Quasi Hoquetus (1985) ................./.7:..=..1.........................................Sofia Gubaidulina (b. 1931) Luke fitzpatrick, viola Jamael Smith, bassoon Steven Damouni, piano String Quartet (1964) ........................~.?:.~ ..?:.? ........................Witold Lutoslawski (1913-1994) Introductory Movement Main Movement Luke Fitzpatrick, violin Vijay Chalasani, viola Allion Salvador, violin Hye Jung Yang, cello Program Notes by Luke Fitzpatrick Except Where Noted Piece pour pianoet quatuor acordes(1991) by Olivier Messiaen is one' -

MALCOLM FRAGER COLLECTION (2013 Gift)

MALCOLM FRAGER COLLECTION (2013 Gift) RUTH T. WATANABE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS SIBLEY MUSIC LIBRARY EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER Processed by Jacek Blaszkiewicz, summer 2015 Revised by David Peter Coppen, spring 2017 1 Vladimir Ashkenazy and Malcolm Frager. Photograph attributed to New York Times Staff Photographer (ca. 1966). From Malcolm Frager Collection, Box 11, Folder 11. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Description of the Collection . 4 Description of Series . 6 SUB-GROUP I: PERSONAL PAPERS Series 1: Correspondence . 8 Series 2: Publicity . 15 Series 3: Business papers . 16 Series 4: Biographical and other personal papers . 17 Series 5: Concert programs . 18 Series 6: Awards . 19 Series 7: Sound recordings . 21 Series 8: Oversized items . 25 SUB-GROUP II: SCORES Series 1: Inscribed to Malcolm Frager . 26 Series 2: Annotated by Malcolm Frager . 27 3 DESCRIPTION OF THE COLLECTION Shelf location M3A 1,1—1,6 Physical extent: 18 linear feet Biographical sketch Photograph of Malcolm Frager from CAMI publicity circular. From Malcolm Frager Collection (2013 Gift), Box 11, Folder 4. Malcolm Frager (1935-1991), American concert pianist, was born in St. Louis, Missouri, where he attended public school and received his earliest musical training. He earned his baccalaureate at Columbia University, where he studied languages in addition to music. His twin victories in the Leventritt Competition (1959) and the Queen Elisabeth of Belgium Competition (1960) launched his career on an international level. In 1963 he made a tour of the U.S.S.R., on which occasion he performed two-piano repertory with fellow pianist Vladimir Ashkenazy, who would remain a close friend of Mr. -

LE MONDE Mort De Christophe Desjardins, Un Alto Pour La Musique De Tous Les Temps

LE MONDE Mort de Christophe Desjardins, un alto pour la musique de tous les temps L’instrumentiste français, soliste à l’Ensemble intercontemporain durant deux décennies et interprète privilégié des plus grands compositeurs, est mort jeudi à 57 ans. Par Marie-Aude Roux Publié le 15 février 2020 Il avait su faire de son instrument une arme de création massive : l’altiste Christophe Desjardins, bien connu des mélomanes amis de la musique contemporaine, est mort à Paris jeudi 13 février des suites d’un cancer. Il avait 57 ans. L’un de ses enregistrements maîtres restera le somptueux récital réalisé pour Aeon, Alto/Multiples, en 2010, dix-sept pièces en 2 CD, dont le premier rassemble des grands solos (d’Hindemith à Elliott Carter) qui ont jalonné le XXe siècle, le second regroupant des œuvres en lien avec un répertoire plus ancien ou réclamant le procédé du re-recording afin de démultiplier son instrument – ainsi, le trio Ockeghem-Maderna, le quatuor de Wolfgang Rihm ou le septuor Messagesquisse de Boulez, dont il a créé en 2000 la version pour sept altos. Christophe Desjardins naît à Caen (Calvados) le 24 avril 1962. Il commence la musique très jeune et étudie d’abord le piano, avant de découvrir l’alto à 10 ans, dont le côté mystérieux le séduit. Il entre au Conservatoire national supérieur de musique de Paris en 1982 dans les classes de Serge Collot pour l’alto, de Geneviève Joy (femme d’Henri Dutilleux) pour la musique de chambre. Muni d’un Premier Prix à l’unanimité l’année suivante (1983), il se perfectionne à la Hochschule der Künste (actuelle Universität der Künste) de Berlin auprès de Bruno Giuranna. -

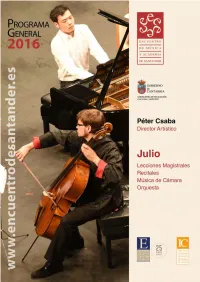

Programa2016.Pdf

l Encuentro de Música y Academia cumple un año más el reto de superarse a sí mismo. La programación de 2016 combina a la perfección la academia, la experiencia y el virtuosismo de los más grandes, como el maestro Krzysztof Penderecki, con la frescura, las ganas y el entusiasmo de los jóvenes músicos Eparticipantes en esta cita ineludible cada verano en Cantabria. Más de 50 conciertos en los escenarios del Palacio de Festivales de Cantabria, en el Palacio de La Magdalena y en otras 22 localidades acercarán la Música con mayúsculas a todos los rincones de la Comunidad Autónoma para satisfacer a un público exigente y siempre ávido de manifestaciones culturales. Para esta tierra, es un privilegio la oportunidad de engrandecer su calendario cultural con un evento de tanta relevancia nacional e internacional. Así pues, animo a todos los cántabros y a quienes nos visitan en estas fechas estivales a disfrutar al máximo de los grandes de la música y a aportar con su presencia la excelente programación que, un verano más, nos ofrece el Encuentro de Música y Academia. Miguel Ángel Revilla Presidente del Gobierno de Cantabria esde hace ya 16 años, el Encuentro de Música y Academia de Santander sigue fielmente las líneas maestras que lo han convertido en un elemento muy prestigioso del verano musical europeo. En Santander —que es una delicia en el mes de julio— se reúnen jóvenes músicos seleccionados uno a uno mediante audición en las escuelas de mayor prestigio Dde Europa, incluida, naturalmente, la Reina Sofía de Madrid. Comparten clases magistrales, ensayos y conciertos con una serie igualmente extraordinaria de profesores, los más destacados de cada instrumento en el panorama internacional. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 93, 1973-1974

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA Music Director COLIN DAVIS & MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS Principal Guest Conductors NINETY-THIRD SEASON 1973-1974 THURSDAY A6 FRIDAY-SATURDAY 22 THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. TALCOTT M. BANKS President PHILIP K. ALLEN SIDNEY STONEMAN JOHN L. THORNDIKE Vice-President Vice-President Treasurer VERNON R. ALDEN MRS HARRIS FAHNESTOCK JOHN T. NOONAN ALLEN G. BARRY HAROLD D. HODGKINSON MRS JAMES H. PERKINS MRS JOHN M. BRADLEY E. MORTON JENNINGS JR IRVING W. RABB RICHARD P. CHAPMAN EDWARD M. KENNEDY PAUL C. REARDON ABRAM T. COLLIER EDWARD G. MURRAY MRS GEORGE LEE SARGENT ARCHIE C EPPS III JOHN HOYT STOOKEY TRUSTEES EMERITUS HENRY B. CABOT HENRY A. LAUGHLIN PALFREY PERKINS FRANCIS W. HATCH EDWARD A. TAFT ADMINISTRATION OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA THOMAS D. PERRY JR THOMAS W. MORRIS Executive Director Manager PAUL BRONSTEIN JOHN H. CURTIS MARY H. SMITH Business Manager Public Relations Director Assistant to the Manager FORRESTER C. SMITH DANIEL R. GUSTIN RICHARD C. WHITE Development Director Administrator of Assistant to Educational Affairs the Manager DONALD W. MACKENZIE JAMES F. KILEY Operations Manager, Operations Manager, Symphony Hall Tanglewood HARRY NEVILLE Program Editor Copyright © 1974 by Boston Symphony Orchestra Inc. SYMPHONY HALL BOSTON MASSACHUSETTS ^H jgfism SPRING LINES" Outline your approach to spring. In greater detail with our hand- somely tailored, single breasted, navy wool worsted coat. Subtly smart with yoked de- tail at front and back. Elegantly fluid with back panel. A refined spring line worth wearing. $150. Coats. Boston Chestnut Hill Northshore Shopping Center South Shore PlazaBurlington Mall Wellesley BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA Music Director COLIN DAVIS & MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS Principal Guest Conductors NINETY-THIRD SEASON 1973-1974 THE BOARD OF OVERSEERS OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC.