Perspectives on the Aesthetics & Phenomenology Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOXA Festival 2004

2 table of contents General Festival Information - Tickets, Venues 3 The Documentary Media Society 5 Acknowledgements 6 Partnership Opportunities 7 Greetings 9 Welcome from DOXA 11 Opening Night - The Take 13 Gals of the Great White North: Movies by Canadian Women 14 Inheritance: A Fisherman’s Story 15 Mumbai, India. January, 2004. The World Social Forum. by Arlene Ami 16 Activist Documentaries 18 Personal Politics by Ann Marie Fleming 19 Sherman’s March 20 NFB Master Class with Alanis Obomsawin 21 Festival Schedule 23 Fragments of a Journey in Palestine-Israel 24 Born Into Brothels 25 The Cucumber Incident 26 No Place Called Home 27 Word Wars 29 Trouble in the Image by Alex MacKenzie 30 The Exhibitionists 31 Haack: The King of Techno + Sid Vision 33 A Night Out with the Guys (Reeking of Humanity) 34 Illustrating the Point: The Use of Animation in Documentary 36 Closing Night - Screaming Men 39 Sources 43 3 4 general festival information Tickets Venues Opening Night Fundraising Gala: The Vogue Theatre (VT) 918 Granville Street $20 regular / $10 low income (plus $1.50 venue fee) Pacific Cinémathèque (PC) 1131 Howe Street low income tickets ONLY available at DOXA office (M-F, 10-5pm) All programs take place at Pacific Cinémathèque except Tuesday May Matinee (before 6 pm) screenings: $7 25 - The Take, which is at the Vogue Theatre. Evening (after 6 pm) screenings: $9 Closing Night: $15 screening & reception The Vogue Theatre and Pacific Cinémathèque are Festival Pass: $69 includes closing gala screening & wheelchair accessible. reception (pass excludes Opening Gala) Master Class: Free admission Festival Information www.doxafestival.ca Festival passes are available at Ticketmaster only (pass 604.646.3200 excludes opening night). -

Cyberarts 2021 Since Its Inception in 1987, the Prix Ars Electronica Has Been Honoring Creativity and Inno- Vativeness in the Use of Digital Media

Documentation of the Prix Ars Electronica 2021 Lavishly illustrated and containing texts by the prize-winning artists and statements by the juries that singled them out for recognition, this catalog showcases the works honored by the Prix Ars Electronica 2021. The Prix Ars Electronica is the world’s most time-honored media arts competition. Winners are awarded the coveted Golden Nica statuette. Ever CyberArts 2021 since its inception in 1987, the Prix Ars Electronica has been honoring creativity and inno- vativeness in the use of digital media. This year, experts from all over the world evaluated Prix Ars Electronica S+T+ARTS 3,158 submissions from 86 countries in four categories: Computer Animation, Artificial Intelligence & Life Art, Digital Musics & Sound Art, and the u19–create your world com - Prize ’21 petition for young people. The volume also provides insights into the achievements of the winners of the Isao Tomita Special Prize and the Ars Electronica Award for Digital Humanity. ars.electronica.art/prix STARTS Prize ’21 STARTS (= Science + Technology + Arts) is an initiative of the European Commission to foster alliances of technology and artistic practice. As part of this initiative, the STARTS Prize awards the most pioneering collaborations and results in the field of creativity 21 ’ and innovation at the intersection of science and technology with the arts. The STARTS Prize ‘21 of the European Commission was launched by Ars Electronica, BOZAR, Waag, INOVA+, T6 Ecosystems, French Tech Grande Provence, and the Frankfurt Book Fair. This Prize catalog presents the winners of the European Commission’s two Grand Prizes, which honor Innovation in Technology, Industry and Society stimulated by the Arts, and more of the STARTS Prize ‘21 highlights. -

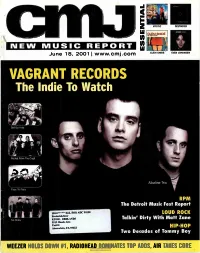

VAGRANT RECORDS the Lndie to Watch

VAGRANT RECORDS The lndie To Watch ,Get Up Kids Rocket From The Crypt Alkaline Trio Face To Face RPM The Detroit Music Fest Report 130.0******ALL FOR ADC 90198 LOUD ROCK Frederick Gier KUOR -REDLANDS Talkin' Dirty With Matt Zane No Motiv 5319 Honda Ave. Unit G Atascadero, CA 93422 HIP-HOP Two Decades of Tommy Boy WEEZER HOLDS DOWN el, RADIOHEAD DOMINATES TOP ADDS AIR TAKES CORE "Tommy's one of the most creative and versatile multi-instrumentalists of our generation." _BEN HARPER HINTO THE "Geggy Tah has a sleek, pointy groove, hitching the melody to one's psyche with the keen handiness of a hat pin." _BILLBOARD AT RADIO NOW RADIO: TYSON HALLER RETAIL: ON FEDDOR BILLY ZARRO 212-253-3154 310-288-2711 201-801-9267 www.virginrecords.com [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 2001 VIrg. Records Amence. Inc. FEATURING "LAPDFINCE" PARENTAL ADVISORY IN SEARCH OF... EXPLICIT CONTENT %sr* Jeitetyr Co owe Eve« uuwEL. oles 6/18/2001 Issue 719 • Vol 68 • No 1 FEATURES 8 Vagrant Records: become one of the preeminent punk labels The Little Inclie That Could of the new decade. But thanks to a new dis- Boasting a roster that includes the likes of tribution deal with TVT, the label's sales are the Get Up Kids, Alkaline Trio and Rocket proving it to be the indie, punk or otherwise, From The Crypt, Vagrant Records has to watch in 2001. DEPARTMENTS 4 Essential 24 New World Our picks for the best new music of the week: An obit on Cameroonian music legend Mystic, Clem Snide, Destroyer, and Even Francis Bebay, the return of the Free Reed Johansen. -

Autotune Bc.Pdf

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Filozofická fakulta Ústav hudební vědy Teorie interaktivních médií BAKALÁŘSKÁ DIPLOMOVÁ PRÁCE Fenomén auto-tune jako projev automatizace a dehumanizace hudby Václav Římánek Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Aleš Opekar, CSc. 2016 ČESTNÉ PROHLÁŠENÍ Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně. Ve své práci jsem použil zdroje a literaturu, které jsou náležitě a řádně citovány v poznámkách pod čarou a jsou všechny uvedeny v bibliografii této práce. V Brně, 11.5. 2016 .................................................. Václav Římánek 2 PODĚKOVÁNÍ Na tomto místě bych chtěl poděkovat PhDr. Aleši Opekarovi, CSc. za vedení, konzultace a přínosné poznámky pro danou práci. Dále bych chtěl poděkovat všem, kteří mě při psaní této práce podporovali. 3 Obsah Úvod.....................................................................................................................................................5 1. Co je to auto-tune?............................................................................................................................6 1.1. Obecná definice........................................................................................................................6 1.2. Jak auto-tune funguje................................................................................................................6 2. Historie.............................................................................................................................................8 2.1. Předchůdci auto-tune................................................................................................................8 -

BEAUTIFUL NOISE Directions in Electronic Music

BEAUTIFUL NOISE Directions in Electronic Music www.ele-mental.org/beautifulnoise/ A WORK IN PROGRESS (3rd rev., Oct 2003) Comments to [email protected] 1 A Few Antecedents The Age of Inventions The 1800s produce a whole series of inventions that set the stage for the creation of electronic music, including the telegraph (1839), the telephone (1876), the phonograph (1877), and many others. Many of the early electronic instruments come about by accident: Elisha Gray’s ‘musical telegraph’ (1876) is an extension of his research into telephone technology; William Du Bois Duddell’s ‘singing arc’ (1899) is an accidental discovery made from the sounds of electric street lights. “The musical telegraph” Elisha Gray’s interesting instrument, 1876 The Telharmonium Thaddeus Cahill's telharmonium (aka the dynamophone) is the most important of the early electronic instruments. Its first public performance is given in Massachusetts in 1906. It is later moved to NYC in the hopes of providing soothing electronic music to area homes, restaurants, and theatres. However, the enormous size, cost, and weight of the instrument (it weighed 200 tons and occupied an entire warehouse), not to mention its interference of local phone service, ensure the telharmonium’s swift demise. Telharmonic Hall No recordings of the instrument survive, but some of Cahill’s 200-ton experiment in canned music, ca. 1910 its principles are later incorporated into the Hammond organ. More importantly, Cahill’s idea of ‘canned music,’ later taken up by Muzak in the 1960s and more recent cable-style systems, is now an inescapable feature of the contemporary landscape. -

3 PC. Skillet Set 16

Page 6. CLOVIS NEWS-JOURNAL, Sun., Sept., 15, 1974 bum also works in a vocal ord "Snowflakes Are Dancing group for accents. (The Newest Sound of Debus- French mountaineer Rock Musician Gets Better This is jazz with a different sy)." Isao Tomita, the Japa- nese maestro of the Moog syn- has gotten the axe By ROBIN WKIJ.ES since that I,P and proves sound. the new in a new LP for RCA can understand every word. else. He plays the alto sax and thesizer, has produced an al- A French mountaineer was Copley News Service Young is as good a writer as called "Perry." To show that Her new album for United HOU.YWOOn- To borrow it's something to hear on his bum that should please both barred from Nepal (of five he is a musician and singer. Artists, pegged on her hit, Conway Twitty has another ;i Madison Avenue phrase, he can still do it, Como in- new album for Blue Note, classicists and devotees of years and fined $800 after four His distinctive voice comes cludes his current hit, "I'll Do Anything It Takes," called "Sweet Lou." fine album, "Honky Tonk An- YuunK isn't getting older — through clear and in complete electronic music. His tongue- members of his 12-man expe- "Weave Me the Sunshine," a comes acorss like a winner. This is not the ordinary kind gel," out on the MCA label. in-cheek rendition of "Golli- he's getting better. Neil control and his guitar and Twitty's own style comes out dition illegally climbed Mt. -

RCA Consolidated Series, Continued

RCA Discography Part 18 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Consolidated Series, Continued 2500 RCA Red Seal ARL 1 2501 – The Romantic Flute Volume 2 – Jean-Pierre Rampal [1977] (Doppler) Concerto In D Minor For 2 Flutes And Orchestra (With Andraìs Adorjaìn, Flute)/(Romberg) Concerto For Flute And Orchestra, Op. 17 2502 CPL 1 2503 – Chet Atkins Volume 1, A Legendary Performer – Chet Atkins [1977] Ain’tcha Tired of Makin’ Me Blue/I’ve Been Working on the Guitar/Barber Shop Rag/Chinatown, My Chinatown/Oh! By Jingo! Oh! By Gee!/Tiger Rag//Jitterbug Waltz/A Little Bit of Blues/How’s the World Treating You/Medley: In the Pines, Wildwood Flower, On Top of Old Smokey/Michelle/Chet’s Tune APL 1 2504 – A Legendary Performer – Jimmie Rodgers [1977] Sleep Baby Sleep/Blue Yodel #1 ("T" For Texas)/In The Jailhouse Now #2/Ben Dewberry's Final Run/You And My Old Guitar/Whippin' That Old T.B./T.B. Blues/Mule Skinner Blues (Blue Yodel #8)/Old Love Letters (Bring Memories Of You)/Home Call 2505-2509 (no information) APL 1 2510 – No Place to Fall – Steve Young [1978] No Place To Fall/Montgomery In The Rain/Dreamer/Always Loving You/Drift Away/Seven Bridges Road/I Closed My Heart's Door/Don't Think Twice, It's All Right/I Can't Sleep/I've Got The Same Old Blues 2511-2514 (no information) Grunt DXL 1 2515 – Earth – Jefferson Starship [1978] Love Too Good/Count On Me/Take Your Time/Crazy Feelin'/Crazy Feeling/Skateboard/Fire/Show Yourself/Runaway/All Nite Long/All Night Long APL 1 2516 – East Bound and Down – Jerry -

The Snow Miser Song 6Ix Toys - Tomorrow's Children (Feat

(Sandy) Alex G - Brite Boy 1910 Fruitgum Company - Indian Giver 2 Live Jews - Shake Your Tuchas 45 Grave - The Snow Miser Song 6ix Toys - Tomorrow's Children (feat. MC Kwasi) 99 Posse;Alborosie;Mama Marjas - Curre curre guagliò still running A Brief View of the Hudson - Wisconsin Window Smasher A Certain Ratio - Lucinda A Place To Bury Strangers - Straight A Tribe Called Quest - After Hours Édith Piaf - Paris Ab-Soul;Danny Brown;Jhene Aiko - Terrorist Threats (feat. Danny Brown & Jhene Aiko) Abbey Lincoln - Lonely House - Remastered Abbey Lincoln - Mr. Tambourine Man Abner Jay - Woke Up This Morning ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE - Are We Experimental? Adolescents - Democracy Adrian Sherwood - No Dog Jazz Afro Latin Vintage Orchestra - Ayodegi Afrob;Telly Tellz;Asmarina Abraha - 808 Walza Afroman - I Wish You Would Roll A New Blunt Afternoons in Stereo - Kalakuta Republik Afu-Ra - Whirlwind Thru Cities Against Me! - Transgender Dysphoria Blues Aim;Qnc - The Force Al Jarreau - Boogie Down Alabama Shakes - Joe - Live From Austin City Limits Albert King - Laundromat Blues Alberta Cross - Old Man Chicago Alex Chilton - Boplexity Alex Chilton;Ben Vaughn;Alan Vega - Fat City Alexia;Aquilani A. - Uh La La La AlgoRythmik - Everybody Gets Funky Alice Russell - Humankind All Good Funk Alliance - In the Rain Allen Toussaint - Yes We Can Can Alvin Cash;The Registers - Doin' the Ali Shuffle Amadou & Mariam - Mon amour, ma chérie Ananda Shankar - Jumpin' Jack Flash Andrew Gold - Thank You For Being A Friend Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness - Brooklyn, You're -

Electronic Music

ELECTRONIC MUSIC Definitions Electronic music refers to music that emphasizes the use of electronic musical instruments or electronic music technology as a central aspect of the sound of the music. Basics Electronic music refers to music that emphasizes the use of electronic musical instruments or electronic music technology as a central aspect of the sound of the music. Historically electronic music was considered to be any music created with the use of electronic musical instruments or electronic processing, but in modern times, that distinction has been lost because almost all recorded music today, and the majority of live music performances, depends on extensive use of electronics. Today, the term electronic music serves to differentiate music that uses electronics as its focal point or inspiration, from music that uses electronics mainly in service of creating an intended production that may have some electronic elements in the sound but does not focus upon them. Contemporary electronic music expresses both art music forms including electronic art music, experimental music, musique concrète, and others; and popular music forms including multiple styles of dance music such as techno, house, trance, electro, breakbeat, drum and bass, industrial music, synth pop, etc. A distinction can be made between instruments that produce sound through electromechanical means as opposed to instruments that produce sound using electronic components. Examples of electromechanical instruments are the teleharmonium, Hammond B3, and the electric guitar, whereas examples of electronic instruments are a Theremin, synthesizer, and a computer. History Late 19th century to early 20th century Before electronic music, there was a growing desire for composers to use emerging technologies for musical purposes. -

Youtube Nightstick

Iron Claw - Skullcrusher - 1970 - YouTube Damon -[1]- Song Of A Gypsy - YouTube Chromakey Dreamcoat - YouTube Nightstick - Dream of the Witches' Sabbath/Massacre of Innocence (Air Attack) - YouTube Nightstick - Four More Years - YouTube Orange Goblin - The Astral Project - YouTube Orange Goblin - Nuclear Guru - YouTube Skepticism - Sign of the Storm - YouTube Cavity - Chase - YouTube Supercollider - YouTube Satin Black - YouTube Today Is The Day - Willpower - 2 - My First Knife - YouTube Alex G - Gnaw - YouTube Stereo Total - Baby Revolution - YouTube Add N To (X) Metal Fingers In My Body - YouTube 'Samurai' by X priest X (Official) - YouTube Bachelorette - I Want to be Your Girlfriend (Bored to Death ending credits) - YouTube Bachelorette - Her Rotating Head (Official) - YouTube The Bug - 'Fuck a Bitch' ft. Death Grips - YouTube Stumble On Tapes - Girlpool - YouTube Joanna Gruesome - Talking To Yr Dick - YouTube Joanna Gruesome - Lemonade Grrl - YouTube BLACK DIRT OAK "Demon Directive" - YouTube Black Dirt Oak - From The Jaguar Priest - YouTube alternative tv how much longer - YouTube Earthless - Lost in the Cold Sun - YouTube Electric Moon - The Doomsday Machine (2011) [Full Album] - YouTube CWC Music Video Holding Out For a Hero - YouTube La Femme - Psycho Tropical Berlin (Full Album) - YouTube Reverend Alicia - YouTube The Phi Mu Washboard Band - Love Hurts - YouTube BJ SNOWDEN IN CANADA - YouTube j-walk - plastic face (prod. cat soup) - YouTube BABY KAELY "SNEAKERHEAD" AMAZING 9 YEAR OLD RAPPER - YouTube Bernard + Edith - Heartache -

Estudio, Analisis E Implementación Del Vocoder Mediante Procesado

ESCOLA TÈCNICA SUPERIOR D’ENGINYERIA ELECTRÒNICA I INFORMÀTICA LA SALLE PROJECTE FI DE CARRERA ENGINYERIA EN TELECOMUNICACIÓ Estudio, Analisis e implementación del Vocoder mediante procesado digital de la señal ALUMNE PROFESSOR PONENT Daniel Alonso Laguna Xavier Sevillano Domínguez ACTA DE L'EXAMEN DEL PROJECTE FI DE CARRERA Reunit el Tribunal qualificador en el dia de la data, l'alumne D. Daniel Alonso Laguna va exposar el seu Projecte de Fi de Carrera, el qual va tractar sobre el tema següent: Acabada l'exposició i contestades per part de l'alumne les objeccions formulades pels Srs. membres del tribunal, aquest valorà l'esmentat Projecte amb la qualificació de Barcelona, VOCAL DEL TRIBUNAL VOCAL DEL TRIBUNAL PRESIDENT DEL TRIBUNAL 2 DANIEL ALONSO LAGUNA VOCODER ANALYSIS AND IMPLEMENTATION TROUGH DIGITAL SIGNAL PROCESSING Canoas, 2009 3 DANIEL ALONSO LAGUNA VOCODER ANALYSIS AND IMPLEMENTATION TROUGH DIGITAL SIGNAL PROCESSING Trabalho de Conclusão apresentado para a banca examinadora do curso de Engenharia de Telecomunicações do Centro Universitário La Salle – Unilasalle, como exigência parcial para a obtenção do grau de Bacharel em Engenharia de Telecomunicações, sob orientação do Professor Ms. Alexandre Gaspary Haupt. CANOAS, 2009 4 AGRADECIMENTOS À mis padres, por el apoyo incondicional y darme la posibilidad de estudiar todo lo que he querido. A mi novia por el cariño, confianza y paciencia que siempre tuvo con mis labores de eterno estudiante, espero que el fin de mis dias de estudiante acaben pronto pero que nunca deje de aprender contigo. A los profesores a ambos lados del ‗charco‘ que me ayudaron, influenciaron y siempre me dieron algo de luz cuando todo estaba negro. -

ELEKTRONISCHE MUSIK and SOUND SYNTHESIS Serialism Serialism Was First Developed by Arnold Schoenberg in the Early 1920'S. It I

ELEKTRONISCHE MUSIK AND SOUND SYNTHESIS Serialism Serialism was first developed by Arnold Schoenberg in the early 1920's. It is a method of com- position whereby all 12 notes of the equal tempered scale are organised in a fixed permuta- tion/order/series. The piece of music is then constructed entirely out of this series, or closely related variations such as retrograde (reversed) or inversion (flipped upside down)1. Composers then extended this techniques to elements other than pitch, such as rhythms and tim- bre, and eventually began to control all of these elements using serialism simultaneously, and this became known as total serialism2. Elektronische Musik Elektronische Musik, was a term originally coined by the German's Werner Meyer-Eppler, Her- bert Eimert, and Bobert Beyer, to describe their approach to creating electronic music (obvi- ously it translates as `electronic music') in the early 1950's (so shortly after the creation of the first pieces of Musique Concr`ete). Elektronische Musik differed from Musique Concr`ete on 2 fundamental levels: (1) All of the sounds were to be created by electronic oscillators (Additive Synthesis) and noise generators (Subtractive Synthesis), i.e.: • They were striving to create entirely new sounds, not use sounds from the real world (2) All of the sounds were organised using total serialism, i.e.: • Elektronische Musik pieces began as an abstract plan, and then the sounds were created to achieve this plan (remember in Musique Concr`ete the music was abstracted from the sounds themselves). Karlheinz Stochausen (who had worked with Pierre Schaefer at the RTF studio in Paris) is probably the most famous of the Elektronische Musik composers.