BEAUTIFUL NOISE Directions in Electronic Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WEB KARAOKE EN-NL.Xlsx

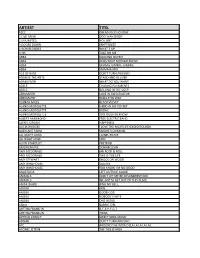

ARTIEST TITEL 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 2 LIVE CREW DOO WAH DIDDY 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 4 NON BLONDES WHAT´S UP A HA TAKE ON ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA DOES YOUR MOTHER KNOW ABBA GIMMIE GIMMIE GIMMIE ABBA MAMMA MIA ACE OF BASE DON´T TURN AROUND ADAM & THE ANTS STAND AND DELIVER ADAM FAITH WHAT DO YOU WANT ADELE CHASING PAVEMENTS ADELE ROLLING IN THE DEEP AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR AEROSMITH WALK THIS WAY ALANAH MILES BLACK VELVET ALANIS MORISSETTE HAND IN MY POCKET ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW ALBERT HAMMOND FREE ELECTRIC BAND ALEXIS JORDAN HAPPINESS ALICIA BRIDGES I LOVE THE NIGHTLIFE (DISCO ROUND) ALIEN ANT FARM SMOOTH CRIMINAL ALL NIGHT LONG LIONEL RICHIE ALL RIGHT NOW FREE ALVIN STARDUST PRETEND AMERICAN PIE DON MCLEAN AMY MCDONALD MR ROCK & ROLL AMY MCDONALD THIS IS THE LIFE AMY STEWART KNOCK ON WOOD AMY WINEHOUSE VALERIE AMY WINEHOUSE YOU KNOW I´M NO GOOD ANASTACIA LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE ANIMALS DON´T LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD ANIMALS WE GOTTA GET OUT OF THIS PLACE ANITA WARD RING MY BELL ANOUK GIRL ANOUK GOOD GOD ANOUK NOBODY´S WIFE ANOUK ONE WORD AQUA BARBIE GIRL ARETHA FRANKLIN R-E-S-P-E-C-T ARETHA FRANKLIN THINK ARTHUR CONLEY SWEET SOUL MUSIC ASWAD DON´T TURN AROUND ATC AROUND THE WORLD (LA LA LA LA LA) ATOMIC KITTEN THE TIDE IS HIGH ARTIEST TITEL ATOMIC KITTEN WHOLE AGAIN AVRIL LAVIGNE COMPLICATED AVRIL LAVIGNE SK8TER BOY B B KING & ERIC CLAPTON RIDING WITH THE KING B-52´S LOVE SHACK BACCARA YES SIR I CAN BOOGIE BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE YOU AIN´T SEEN NOTHING YET BACKSTREET BOYS -

'What Ever Happened to Breakdancing?'

'What ever happened to breakdancing?' Transnational h-hoy/b-girl networks, underground video magazines and imagined affinities. Mary Fogarty Submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Interdisciplinary MA in Popular Culture Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario © November 2006 For my sister, Pauline 111 Acknowledgements The Canada Graduate Scholarship (SSHRC) enabled me to focus full-time on my studies. I would also like to express my deepest gratitude to my committee members: Andy Bennett, Hans A. Skott-Myhre, Nick Baxter-Moore and Will Straw. These scholars have shaped my ideas about this project in crucial ways. I am indebted to Michael Zryd and Francois Lukawecki for their unwavering kindness, encouragement and wisdom over many years. Steve Russell patiently began to teach me basic rules ofgrammar. Barry Grant and Eric Liu provided comments about earlier chapter drafts. Simon Frith, Raquel Rivera, Anthony Kwame Harrison, Kwande Kefentse and John Hunting offered influential suggestions and encouragement in correspondence. Mike Ripmeester, Sarah Matheson, Jeannette Sloniowski, Scott Henderson, Jim Leach, Christie Milliken, David Butz and Dale Bradley also contributed helpful insights in either lectures or conversations. AJ Fashbaugh supplied the soul food and music that kept my body and mind nourished last year. If AJ brought the knowledge then Matt Masters brought the truth. (What a powerful triangle, indeed!) I was exceptionally fortunate to have such noteworthy fellow graduate students. Cole Lewis (my summer writing partner who kept me accountable), Zorianna Zurba, Jana Tomcko, Nylda Gallardo-Lopez, Seth Mulvey and Pauline Fogarty each lent an ear on numerous much needed occasions as I worked through my ideas out loud. -

DOXA Festival 2004

2 table of contents General Festival Information - Tickets, Venues 3 The Documentary Media Society 5 Acknowledgements 6 Partnership Opportunities 7 Greetings 9 Welcome from DOXA 11 Opening Night - The Take 13 Gals of the Great White North: Movies by Canadian Women 14 Inheritance: A Fisherman’s Story 15 Mumbai, India. January, 2004. The World Social Forum. by Arlene Ami 16 Activist Documentaries 18 Personal Politics by Ann Marie Fleming 19 Sherman’s March 20 NFB Master Class with Alanis Obomsawin 21 Festival Schedule 23 Fragments of a Journey in Palestine-Israel 24 Born Into Brothels 25 The Cucumber Incident 26 No Place Called Home 27 Word Wars 29 Trouble in the Image by Alex MacKenzie 30 The Exhibitionists 31 Haack: The King of Techno + Sid Vision 33 A Night Out with the Guys (Reeking of Humanity) 34 Illustrating the Point: The Use of Animation in Documentary 36 Closing Night - Screaming Men 39 Sources 43 3 4 general festival information Tickets Venues Opening Night Fundraising Gala: The Vogue Theatre (VT) 918 Granville Street $20 regular / $10 low income (plus $1.50 venue fee) Pacific Cinémathèque (PC) 1131 Howe Street low income tickets ONLY available at DOXA office (M-F, 10-5pm) All programs take place at Pacific Cinémathèque except Tuesday May Matinee (before 6 pm) screenings: $7 25 - The Take, which is at the Vogue Theatre. Evening (after 6 pm) screenings: $9 Closing Night: $15 screening & reception The Vogue Theatre and Pacific Cinémathèque are Festival Pass: $69 includes closing gala screening & wheelchair accessible. reception (pass excludes Opening Gala) Master Class: Free admission Festival Information www.doxafestival.ca Festival passes are available at Ticketmaster only (pass 604.646.3200 excludes opening night). -

2011-11-25 1. När Det Är Spelning På Nuclear Nation Brukar Det Komma

Nuclear Nation Quiz - 2011-11-25 1. När det är spelning på Nuclear Nation brukar det komma mycket folk. Det gör det ibland även annars och då kan det bli långa köer som ringlar sig runt Linköping. Under tidigt 2000-tal kunde NN- besökare vid ett festtillfälle slippa kötristeseen och gå direkt in på festen förutsatt att de uppfyllde ett krav. Vad skulle två NN-besökare göra för att få gå före i kön? A: Bära likadana kläder B: Kunna texten till Headhunter utantill och sjunga den tvåstämmigt C: Vara fastkedjade i varandra 2. Ni befinner er just nu på synthquiz med den anrika synthföreningen Nuclear Nation, men det var inte helt självklart att vi skulle heta just så. Vilket annat namn fanns som förslag? A: Eclipse B: Solaris C: SUN 3. Apoptygma Berzerk gjorde 98 en spelning i Leipzig från vilken i alla fall en liten del kom med på skivan APBL98. Trots att bandet körde på som hårdast med en Depeche-cover som folk verkade uppskatta, så fick spelningen ett snöpligt slut. Men vad hände? A: Det utbröt en mindre en brand i ljudteknikerbåset pga. underdimensionerade elkablar. B: Spelningen råkade äga rum samma kväll som kraftverket Holzkohle fallerade, vilket ledde till Leipzigs hittills största elavbrott. C: Trots att Apoptygma ville köra en låt till, så stängde polisen ner konserten i förtid. 4. En inställd spelning är också en spelning brukar man säga och ett band som skulle ha spelat på NN för ett antal år sedan, men som tyvärr fick ställa in p.g.a. sjukdom var... ja, vilket band då? A: Covenant B: VNV Nation C: Tyskarna från Lund 5: Ett band som dock har spelat på NN är LOWE. -

Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews На Arrhythmia Sound

2/22/2018 Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews на Arrhythmia Sound Home Content Contacts About Subscribe Gallery Donate Search Interviews Reviews News Podcasts Reports Home » Reviews Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) Submitted by: Quarck | 19.04.2008 no comment | 198 views Aaron Spectre , also known for the project Drumcorps , reveals before us completely new side of his work. In protovoves frenzy breakgrindcore Specter produces a chic downtempo, idm album. Lost Tracks the result of six years of work, but despite this, the rumor is very fresh and original. The sound is minimalistic without excesses, but at the same time the melodies are very beautiful, the bit powerful and clear, pronounced. Just want to highlight the composition of Break Ya Neck (Remix) , a bit mystical and mysterious, a feeling, like wandering somewhere in the http://www.arrhythmiasound.com/en/review/aaron-spectre-lost-tracks-ad-noiseam-2007.html 1/3 2/22/2018 Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews на Arrhythmia Sound dusk. There was a place and a vocal, in a track Degrees the gentle voice Kazumi (Pink Lilies) sounds. As a result, Lost Tracks can be safely put on a par with the works of such mastadonts as Lusine, Murcof, Hecq. Tags: downtempo, idm Subscribe Email TOP-2013 Submit TOP-2014 TOP-2015 Tags abstract acid ambient ambient-techno artcore best2012 best2013 best2014 best2015 best2016 best2017 breakcore breaks cyberpunk dark ambient downtempo dreampop drone drum&bass dub dubstep dubtechno electro electronic experimental female vocal future garage glitch hip hop idm indie indietronica industrial jazzy krautrock live modern classical noir oldschool post-rock shoegaze space techno tribal trip hop Latest The best in 2017 - albums, places 1-33 12/30/2017 The best in 2017 - albums, places 66-34 12/28/2017 The best in 2017. -

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop Dance: Authenticity, and the Commodification of Cultural Identities

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop dance: Authenticity, and the commodification of cultural identities. E. Moncell Durden., Assistant Professor of Practice University of Southern California Glorya Kaufman School of Dance Introduction Hip-hop dance has become one of the most popular forms of dance expression in the world. The explosion of hip-hop movement and culture in the 1980s provided unprecedented opportunities to inner-city youth to gain a different access to the “American” dream; some companies saw the value in using this new art form to market their products for commercial and consumer growth. This explosion also aided in an early downfall of hip-hop’s first dance form, breaking. The form would rise again a decade later with a vengeance, bringing older breakers out of retirement and pushing new generations to develop the technical acuity to extraordinary levels of artistic corporeal genius. We will begin with hip-hop’s arduous beginnings. Born and raised on the sidewalks and playgrounds of New York’s asphalt jungle, this youthful energy that became known as hip-hop emerged from aspects of cultural expressions that survived political abandonment, economic struggles, environmental turmoil and gang activity. These living conditions can be attributed to high unemployment, exceptionally organized drug distribution, corrupt police departments, a failed fire department response system, and Robert Moses’ building of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, which caused middle and upper-class residents to migrate North. The South Bronx lost 600,000 jobs and displaced more than 5,000 families. Between 1973 and 1977, and more than 30,000 fires were set in the South Bronx, which gave rise to the phrase “The Bronx is Burning.” This marginalized the black and Latino communities and left the youth feeling unrepresented, and hip-hop gave restless inner-city kids a voice. -

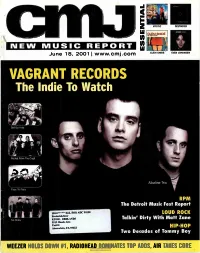

VAGRANT RECORDS the Lndie to Watch

VAGRANT RECORDS The lndie To Watch ,Get Up Kids Rocket From The Crypt Alkaline Trio Face To Face RPM The Detroit Music Fest Report 130.0******ALL FOR ADC 90198 LOUD ROCK Frederick Gier KUOR -REDLANDS Talkin' Dirty With Matt Zane No Motiv 5319 Honda Ave. Unit G Atascadero, CA 93422 HIP-HOP Two Decades of Tommy Boy WEEZER HOLDS DOWN el, RADIOHEAD DOMINATES TOP ADDS AIR TAKES CORE "Tommy's one of the most creative and versatile multi-instrumentalists of our generation." _BEN HARPER HINTO THE "Geggy Tah has a sleek, pointy groove, hitching the melody to one's psyche with the keen handiness of a hat pin." _BILLBOARD AT RADIO NOW RADIO: TYSON HALLER RETAIL: ON FEDDOR BILLY ZARRO 212-253-3154 310-288-2711 201-801-9267 www.virginrecords.com [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 2001 VIrg. Records Amence. Inc. FEATURING "LAPDFINCE" PARENTAL ADVISORY IN SEARCH OF... EXPLICIT CONTENT %sr* Jeitetyr Co owe Eve« uuwEL. oles 6/18/2001 Issue 719 • Vol 68 • No 1 FEATURES 8 Vagrant Records: become one of the preeminent punk labels The Little Inclie That Could of the new decade. But thanks to a new dis- Boasting a roster that includes the likes of tribution deal with TVT, the label's sales are the Get Up Kids, Alkaline Trio and Rocket proving it to be the indie, punk or otherwise, From The Crypt, Vagrant Records has to watch in 2001. DEPARTMENTS 4 Essential 24 New World Our picks for the best new music of the week: An obit on Cameroonian music legend Mystic, Clem Snide, Destroyer, and Even Francis Bebay, the return of the Free Reed Johansen. -

High Concept Music for Low Concept Minds

High concept music for low concept minds Music | Bittles’ Magazine: The music column from the end of the world: August/September New albums reviewed Part 1 Music doesn’t challenge anymore! It doesn’t ask questions, or stimulate. Institutions like the X-Factor, Spotify, EDM and landfill pop chameleons are dominating an important area of culture by churning out identikit pop clones with nothing of substance to say. Opinion is not only frowned upon, it is taboo! By JOHN BITTLES This is why we need musicians like The Black Dog, people who make angry, bitter compositions, highlighting inequality and how fucked we really are. Their new album Neither/Neither is a sonically dense and thrilling listen, capturing the brutal erosion of individuality in an increasingly technological and state-controlled world. In doing so they have somehow created one of the most mesmerising and important albums of the year. Music isn’t just about challenging the system though. Great music comes in a wide variety of formats. Something proven all too well in the rest of the albums reviewed this month. For instance, we also have the experimental pop of Georgia, the hazy chill-out of Nils Frahm, the Vangelis-style urban futurism of Auscultation, the dense electronica of Mueller Roedelius, the deep house grooves of Seb Wildblood and lots, lots more. Somehow though, it seems only fitting to start with the chilling reflection on the modern day systems of state control that is the latest work by UK electronic veterans The Black Dog. Their new album has, seemingly, been created in an attempt to give the dispossessed and repressed the knowledge of who and what the enemy is so they may arm themselves and fight back. -

Apoptygma Berzerk Exit Popularity Contest Mp3, Flac, Wma

Apoptygma Berzerk Exit Popularity Contest mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Exit Popularity Contest Country: US Released: 2016 Style: Electro, Berlin-School, Experimental, Ambient MP3 version RAR size: 1839 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1245 mb WMA version RAR size: 1102 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 296 Other Formats: AHX APE MPC AUD FLAC MP3 MMF Tracklist 1 The Genesis 6 Experiment 9:12 2 Hegelian Dialectic 4:16 3 For Now We See Through A Glass, Darkly 8:30 4 Stille Når Gruppe 5:38 5 In A World Of Locked Rooms 8:56 6 The Cosmic Chess Match 7:35 7 U.T.E.O.T.W. (Instrumental) 6:57 8 The Devil Pays In Counterfeit Money 7:16 9 Rhein Klang 7:03 10 U.T.E.O.T.W. (Extended Version) 9:08 Companies, etc. Licensed To – The End Records Phonographic Copyright (p) – Hard:drive Copyright (c) – Hard:drive Pressed By – Disc Makers – MAI0155 Notes Collection of the rare and limited EPs: Stop Feeding The Beast, Videodrome, and Xenogenesis Includes two exclusive tracks, as well as an exclusive version of UTEOTW (not the same as the 7" version) Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Text): 6 54436 07252 2 Barcode (Scanned): 654436072522 Matrix / Runout: MAI0155 DISC MAKERS Mastering SID Code: IFPI LZ54 Mould SID Code: IFPI ALK01 SPARS Code: ADD Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Apoptygma Exit Popularity Contest The End TE-725-4 TE-725-4 US 2016 Berzerk (Cass, Comp, Ltd) Records Apoptygma Exit Popularity Contest Mrs. -

The DIY Careers of Techno and Drum 'N' Bass Djs in Vienna

Cross-Dressing to Backbeats: The Status of the Electroclash Producer and the Politics of Electronic Music Feature Article David Madden Concordia University (Canada) Abstract Addressing the international emergence of electroclash at the turn of the millenium, this article investigates the distinct character of the genre and its related production practices, both in and out of the studio. Electroclash combines the extended pulsing sections of techno, house and other dance musics with the trashier energy of rock and new wave. The genre signals an attempt to reinvigorate dance music with a sense of sexuality, personality and irony. Electroclash also emphasizes, rather than hides, the European, trashy elements of electronic dance music. The coming together of rock and electro is examined vis-à-vis the ongoing changing sociality of music production/ distribution and the changing role of the producer. Numerous women, whether as solo producers, or in the context of collaborative groups, significantly contributed to shaping the aesthetics and production practices of electroclash, an anomaly in the history of popular music and electronic music, where the role of the producer has typically been associated with men. These changes are discussed in relation to the way electroclash producers Peaches, Le Tigre, Chicks on Speed, and Miss Kittin and the Hacker often used a hybrid approach to production that involves the integration of new(er) technologies, such as laptops containing various audio production softwares with older, inexpensive keyboards, microphones, samplers and drum machines to achieve the ironic backbeat laden hybrid electro-rock sound. Keywords: electroclash; music producers; studio production; gender; electro; electronic dance music Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 4(2): 27–47 ISSN 1947-5403 ©2011 Dancecult http://dj.dancecult.net DOI: 10.12801/1947-5403.2012.04.02.02 28 Dancecult 4(2) David Madden is a PhD Candidate (A.B.D.) in Communications at Concordia University (Montreal, QC). -

Youandmeagainsttheworld.Pdf (9.000Mb)

FORORD Denne oppgaven har sitt utspring i kjærlighet til en musikkgenre, og etter hvert kjærlighet til miljøet rundt akkurat denne genren. Det var sånn den ble til. En stor takk til alle i miljøet som har kommet med talløse oppmuntringer underveis i prosessen med oppgaven, og som har bidratt med informasjon og synspunkter, stort og smått. Og for at miljøet finnes, selv om det var ukjent for meg veldig lenge og jeg trodde jeg var omtrent den eneste i verden som likte denne type musikk. Uten at tre travle popstjerner hadde stilt velvillig opp, hadde oppgaven manglet et viktig aspekt og svært viktig innsikt fra musikkverdenen som ikke menigmann uten videre kan ta del i. Tusen takk til dem for at de tok seg tid til å prate med meg og for at de trodde på prosjektet mitt. Gjennom sin musikk og sine bidrag til oppgaven har de vært en viktig kilde til både inspirasjon og motivasjon. 2 KAPITTELOVERSIKT 1. Innledning med problemstilling side 4 2. Metode side 7 3. Musikkindustrien – og media side 11 3.1 Musikk på radio side 15 3.2 Musikk på tv side 16 4. Symbolsk kapital i forskjellige kulturelle felt side 17 4.1 Bourdieu – ulike former for kapital side 18 4.2 Sosiale og kulturelle felt side 19 4.3 Symbolsk makt side 21 4.4 Subkulturell kapital side 22 5. En kort historie om synth side 26 6. Subkultur – i et teoretisk perspektiv side 29 6.1 Synth som subkultur side 32 7. Bandpresentasjoner side 45 7.1 Apoptygma Berzerk – In This Together side 45 7.2 Combichrist – This Shit Will Fcuk You Up side 58 7.3 Gothminister – Happiness in Darkness side 68 8. -

Czas Na Ambient Festival!

Wiadomości Piątek, 5 lipca 2019 Czas na Ambient Festival! Gorlickie Centrum Kultury serdecznie zaprasza na Międzynarodowe Prezentacje Multimedialne Ambient Festival 2019, które odbędą się w sali teatralnej GCK w dniach 12-13 lipca br. Ambient Festival to impreza prezentująca współczesne odmiany muzyki elektronicznej i elektroakustycznej oraz pokazująca wartościowe przedsięwzięcia z zakresu sztuki „Video Art”. Coraz większa popularność tej odmiany muzyki na całym świecie sprawia, że zajmuje się nią coraz większa ilość muzyków, na co dzień uprawiających jazz, folk, a także muzykę klasyczną. Ideą imprezy jest zainteresowanie szerszej publiczności niekomercyjnymi formami muzyki o najwyższych wartościach artystycznych oraz zapoznanie z najnowszymi trendami w polskiej i światowej muzyce współczesnej. Ze względu na swój „niszowy” charakter gorlicki Ambient Festival jest jedną z najważniejszych tego typu imprez w Polsce oraz jedną z coraz bardziej liczących się w Europie. W roku 2018 Ambient Festival obchodził 20-lecie swego istnienia. Przez ten okres zaprezentowaliśmy osiągnięcia wielu światowej sławy artystów zajmujących się nie tylko muzyką elektroniczną, ale także muzyką klasyczną, folkową czy jazzową. W Gorlicach wystąpili między innymi: Manuel Goetsching, Harald Grosskopff, Hans Joachim Roedelius, Christian Fennesz, Geir Jensen /Biosphere/, Richard Pinhas, Robin Guthrie, Pieter Nooten, Kouhei Matsunaga, Andres Jankowski, Eivind Aarset, Tadeusz Sudnik, Józef Skrzek, Alex Paterson /The Orb/ oraz wielu innych muzyków z niemalże całej Europy. Przez wiele lat koncerty festiwalowe prowadził red. Jerzy Kordowicz. Dyrektorem artystycznym festiwalu jest Tadeusz Łuczejko, laureat konkursu na najlepsze nagranie muzyki elektronicznej, zorganizowanego właśnie przez J. Kordowicza na antenie „Trójki”. Tradycyjnie uruchomiona zostanie giełda płyt /CD i Vinyle/, pokaz audiofilskiego sprzętu grającego. Na tegorocznym festiwalu wystąpią: 12.07 (piątek) – START GODZ.