The DIY Careers of Techno and Drum 'N' Bass Djs in Vienna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

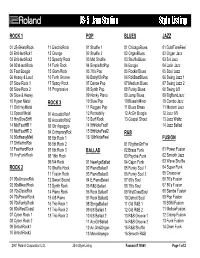

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing ROCK 1 POP BLUES JAZZ 01 JS-5HardRock 11 ElectricRock 01 Shuffle 1 01 ChicagoBlues 01 DublTimeFeel 02 BritHardRck1 12 Grunge 02 Shuffle 2 02 OrganBlues 02 Organ Jazz 03 BritHardRck2 13 Speedy Rock 03 Mid Shuffle 03 ShuffleBlues 03 5/4 Jazz 04 80'sHardRock 14 Funk Rock 04 Simple8btPop 04 Boogie 04 Latin Jazz 05 Fast Boogie 15 Glam Rock 05 70's Pop 05 Rockin'Blues 05 Soul Jazz 06 Heavy & Loud 16 Funk Groove 06 Early80'sPop 06 RckBeatBlues 06 Swing Jazz 1 07 Slow Rock 1 17 Spacy Rock 07 Dance Pop 07 Medium Blues 07 Swing Jazz 2 08 Slow Rock 2 18 Progressive 08 Synth Pop 08 Funky Blues 08 Swing 6/8 09 Slow & Heavy 09 Honky Piano 09 Jump Blues 09 BigBandJazz 10 Hyper Metal ROCK 3 10 Slow Pop 10 BluesInMinor 10 Combo Jazz 11 Old HvyMetal 11 Reggae Pop 11 Blues Brass 11 Modern Jazz 12 Speed Metal 01 AcousticRck1 12 Rockabilly 12 AcGtr Boogie 12 Jazz 6/8 13 HvySlowShffl 02 AcousticRck2 13 Surf Rock 13 Gospel Shout 13 Jazz Waltz 14 MidFastHR 1 03 Gtr Arpeggio 14 8thNoteFeel1 14 Jazz Ballad 15 MidFastHR 2 04 CntmpraryRck 15 8thNoteFeel2 R&B 16 80sHeavyMetl 05 8bt Rock 1 16 16thNoteFeel FUSION 17 ShffleHrdRck 06 8bt Rock 2 01 RhythmGtrFnk 18 FastHardRock 07 8bt Rock 3 BALLAD 02 Brass Funk 01 Power Fusion 19 HvyFunkRock 08 16bt Rock 03 Psyche-Funk 02 Smooth Jazz 09 5/4 Rock 01 NewAgeBallad 04 Cajun Funk 03 Wave Shuffle ROCK 2 10 Shuffle Rock 02 PianoBallad1 05 Funky Soul 1 04 Super Funk 11 Fusion Rock 03 PianoBallad2 06 Funky Soul 2 05 Crossover 01 90sGrooveRck 12 Sweet Sound 04 E.PianoBalad 07 60's Soul 06 -

Chiptuning Intellectual Property: Digital Culture Between Creative Commons and Moral Economy

Chiptuning Intellectual Property: Digital Culture Between Creative Commons and Moral Economy Martin J. Zeilinger York University, Canada [email protected] Abstract This essay considers how chipmusic, a fairly recent form of alternative electronic music, deals with the impact of contemporary intellectual property regimes on creative practices. I survey chipmusicians’ reusing of technology and content invoking the era of 8-bit video games, and highlight points of contention between critical perspectives embodied in this art form and intellectual property policy. Exploring current chipmusic dissemination strategies, I contrast the art form’s links to appropriation-based creative techniques and the ‘demoscene’ amateur hacking culture of the 1980s with the chiptune community’s currently prevailing reliance on Creative Commons licenses for regulating access. Questioning whether consideration of this alternative licensing scheme can adequately describe shared cultural norms and values that motivate chiptune practices, I conclude by offering the concept of a moral economy of appropriation-based creative techniques as a new framework for understanding digital creative practices that resist conventional intellectual property policy both in form and in content. Keywords: Chipmusic, Creative Commons, Moral Economy, Intellectual Property, Demoscene Introduction The chipmusic community, like many other born-digital creative communities, has a rich tradition of embracing and encouraged open access, collaboration, and sharing. It does not like to operate according to the logic of informational capital and the restrictive enclosure movements this logic engenders. The creation of chipmusic, a form of electronic music based on the repurposing of outdated sound chip technology found in video gaming devices and old home computers, centrally involves the reworking of proprietary cultural materials. -

State of Bass

First published by Velocity Press 2020 velocitypress.uk Copyright © Martin James 2020 Cover design: Designment designment.studio Typesetting: Paul Baillie-Lane pblpublishing.co.uk Photography: Cleveland Aaron, Andy Cotterill, Courtney Hamilton, Tristan O’Neill Martin James has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identied as the author of this work All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission from the publisher While the publishers have made every reasonable eort to trace the copyright owners for some of the photographs in this book, there may be omissions of credits, for which we apologise. ISBN: 9781913231026 1: Ag’A THE JUNGLISTS NAMING THE SOUND, LOCATING THE SCENE ‘It always has been such a terrible name. I’ve never known any other type of music to get so misconstrued by its name.’ (Rob Playford, 1996) Of all of the dance music genres, none has been surrounded with quite so much controversy over its name than jungle. No sooner had it been coined than exponents of the scene were up in arms about the racist implications. Arguments raged over who rst used the term and many others simply refused to acknowledge the existence of the moniker. It wasn’t the rst time that jungle had been used as a way to describe a sound. Kool and the Gang had called their 1973 funk standard Jungle Boogie, while an instrumental version with an overdubbed ute part and additional percussion instruments was titled Jungle Jazz. The song ends with a Tarzan yell and features grunting, panting and scatting throughout. -

Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews На Arrhythmia Sound

2/22/2018 Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews на Arrhythmia Sound Home Content Contacts About Subscribe Gallery Donate Search Interviews Reviews News Podcasts Reports Home » Reviews Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) Submitted by: Quarck | 19.04.2008 no comment | 198 views Aaron Spectre , also known for the project Drumcorps , reveals before us completely new side of his work. In protovoves frenzy breakgrindcore Specter produces a chic downtempo, idm album. Lost Tracks the result of six years of work, but despite this, the rumor is very fresh and original. The sound is minimalistic without excesses, but at the same time the melodies are very beautiful, the bit powerful and clear, pronounced. Just want to highlight the composition of Break Ya Neck (Remix) , a bit mystical and mysterious, a feeling, like wandering somewhere in the http://www.arrhythmiasound.com/en/review/aaron-spectre-lost-tracks-ad-noiseam-2007.html 1/3 2/22/2018 Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews на Arrhythmia Sound dusk. There was a place and a vocal, in a track Degrees the gentle voice Kazumi (Pink Lilies) sounds. As a result, Lost Tracks can be safely put on a par with the works of such mastadonts as Lusine, Murcof, Hecq. Tags: downtempo, idm Subscribe Email TOP-2013 Submit TOP-2014 TOP-2015 Tags abstract acid ambient ambient-techno artcore best2012 best2013 best2014 best2015 best2016 best2017 breakcore breaks cyberpunk dark ambient downtempo dreampop drone drum&bass dub dubstep dubtechno electro electronic experimental female vocal future garage glitch hip hop idm indie indietronica industrial jazzy krautrock live modern classical noir oldschool post-rock shoegaze space techno tribal trip hop Latest The best in 2017 - albums, places 1-33 12/30/2017 The best in 2017 - albums, places 66-34 12/28/2017 The best in 2017. -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

Discourse on Disco

Chapter 1: Introduction to the cultural context of electronic dance music The rhythmic structures of dance music arise primarily from the genre’s focus on moving dancers, but they reveal other influences as well. The poumtchak pattern has strong associations with both disco music and various genres of electronic dance music, and these associations affect the pattern’s presence in popular music in general. Its status and musical role there has varied according to the reputation of these genres. In the following introduction I will not present a complete history of related contributors, places, or events but rather examine those developments that shaped prevailing opinions and fields of tension within electronic dance music culture in particular. This culture in turn affects the choices that must be made in dance music production, for example involving the poumtchak pattern. My historical overview extends from the 1970s to the 1990s and covers predominantly the disco era, the Chicago house scene, the acid house/rave era, and the post-rave club-oriented house scene in England.5 The disco era of the 1970s DISCOURSE ON DISCO The image of John Travolta in his disco suit from the 1977 motion picture Saturday Night Fever has become an icon of the disco era and its popularity. Like Blackboard Jungle and Rock Around the Clock two decades earlier, this movie was an important vehicle for the distribution of a new dance music culture to America and the entire Western world, and the impact of its construction of disco was gigantic.6 It became a model for local disco cultures around the world and comprised the core of a common understanding of disco in mainstream popular music culture. -

Music 3500: American Music This Final Exam Is Comprehensive —It Covers the Entire Course (Monday December Starting at 5PM In

FINAL EXAM STUDY GUIDE Music 3500: American Music This final exam is comprehensive —it covers the entire course (Monday December starting at 5PM in Knauss Hall 2452) Exam Format: 70 questions (each question is worth 4 points), plus a 40-point "fill-in-the-chart" (described below) (these two things total a maximum of 320 possible points toward your final course grade total). The format of the 70-question computer-graded section of the final exam will be: ...Matching ...Multiple Choice ...True/False (from text readings, class lectures, YouTube video links) General study recommendations: - Do the online quiz assignments for Chapters 1-9 (these must be completed by Monday April 24) ---------- For the Computer-Graded part of the final exam: 1. Know the definitions of Important Terms at the ends of Chapters 2-8 - Chapter 1 (textbook, page 5) -- know "popular music," "roots music," "Classical art- music" - Chapter 2 (textbook, page 19) -- know "old-time music," "hot jazz," "race music" - Chapter 3 (textbook, page 31) -- know "bebop," "big-band," "boogie-woogie" - Chapter 4 (textbook, page 42) -- know "backbeat," "chance music," "cool jazz," "multi- serialism," "rhythm & blues," "soul" - Chapter 5 (textbook, page 52) -- know "soundtrack," "free jazz" - Chapter 6 (textbook, pages 58-59) -- know "fusion," minimalism," - Chapter 7 (textbook, pages 69-70) -- know "techno," "smooth jazz," "hip-hop" - Chapter 8 (textbook, page 81) -- know "sound art" 2. Know which decade the following music technologies came from: (Review the chronological order of -

PDF Transition

! ! ! ! “FINGERS GLITTERING ABOVE A KEYBOARD:” ! THE KEYBOARD WORKS AND HYBRID CREATIVE PRACTICES OF ! TRISTAN PERICH! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A Dissertation! Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School! of Cornell University! in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of! Doctor of Musical! Arts! ! ! by! David Benjamin Friend! May 2019! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! © 2019 David Benjamin! Friend! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! “FINGERS GLITTERING ABOVE A KEYBOARD:”! THE KEYBOARD WORKS AND HYBRID CREATIVE PRACTICES OF ! TRISTAN! PERICH! ! David Benjamin Friend, D.M.A.! Cornell University,! 2019! ! !This dissertation examines the life and work of Tristan Perich, with a focus on his works for keyboard instruments. Developing an understanding of his creative practices and a familiarity with his aesthetic entails both a review of his personal narrative as well as its intersection with relevant musical, cultural, technological, and generational discourses. This study examines relevant groupings in music, art, and technology articulated to Perich and his body of work including dorkbot and the New Music Community, a term established to describe the generationally-inflected structural shifts! in the field of contemporary music that emerged in New York City in the first several years of the twenty-first century. Perich’s one-bit electronics practice is explored, and its impact on his musical and artistic work is traced across multiple disciplines and a number of aesthetic, theoretical, and technical parameters. This dissertation also substantiates the centrality of the piano to Perich’s compositional process and to his broader aesthetic cosmology. A selection of his works for keyboard instruments are analyzed, and his unique approach to keyboard technique is contextualized in relation to traditional Minimalist piano techniques and his one-bit electronics practice." ! ! BIOGRAPHICAL! SKETCH! ! !! !David Friend (b. -

Complete Band and Panel Listings Inside!

THE STROKES FOUR TET NEW MUSIC REPORT ESSENTIAL October 15, 2001 www.cmj.com DILATED PEOPLES LE TIGRE CMJ MUSIC MARATHON ’01 OFFICIALGUIDE FEATURING PERFORMANCES BY: Bis•Clem Snide•Clinic•Firewater•Girls Against Boys•Jonathan Richman•Karl Denson•Karsh Kale•L.A. Symphony•Laura Cantrell•Mink Lungs• Murder City Devils•Peaches•Rustic Overtones•X-ecutioners and hundreds more! GUEST SPEAKER: Billy Martin (Medeski Martin And Wood) COMPLETE D PANEL PANELISTS INCLUDE: BAND AN Lee Ranaldo/Sonic Youth•Gigi•DJ EvilDee/Beatminerz• GS INSIDE! DJ Zeph•Rebecca Rankin/VH-1•Scott Hardkiss/God Within LISTIN ININ STORESSTORES TUESDAY,TUESDAY, SEPTEMBERSEPTEMBER 4.4. SYSTEM OF A DOWN AND SLIPKNOT CO-HEADLINING “THE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE TOUR” BEGINNING SEPTEMBER 14, 2001 SEE WEBSITE FOR DETAILS CONTACT: STEVE THEO COLUMBIA RECORDS 212-833-7329 [email protected] PRODUCED BY RICK RUBIN AND DARON MALAKIAN CO-PRODUCED BY SERJ TANKIAN MANAGEMENT: VELVET HAMMER MANAGEMENT, DAVID BENVENISTE "COLUMBIA" AND W REG. U.S. PAT. & TM. OFF. MARCA REGISTRADA./Ꭿ 2001 SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT INC./ Ꭿ 2001 THE AMERICAN RECORDING COMPANY, LLC. WWW.SYSTEMOFADOWN.COM 10/15/2001 Issue 735 • Vol 69 • No 5 CMJ MUSIC MARATHON 2001 39 Festival Guide Thousands of music professionals, artists and fans converge on New York City every year for CMJ Music Marathon to celebrate today's music and chart its future. In addition to keynote speaker Billy Martin and an exhibition area with a live performance stage, the event features dozens of panels covering topics affecting all corners of the music industry. Here’s our complete guide to all the convention’s featured events, including College Day, listings of panels by 24 topic, day and nighttime performances, guest speakers, exhibitors, Filmfest screenings, hotel and subway maps, venue listings, band descriptions — everything you need to make the most of your time in the Big Apple. -

7-8Kulturmagazin Cottbus-Lausitz-Kostenlos

Blick licht 7-8 KULTURMAGAZIN COTTBUS-LAUSITZ-KOSTENLOS culture coltura kultur kultur-cottbus.de Inhalt 3 Editorial 4 Lausitz Editorial 5 Studium Weder ultrahighspeed deathmetal noch smothsurfpunk oder trippelfunkygoathrock locken die die Menschen in einen abgeschlossenen Raum. Grillwurst, Bierfässer unter 6-7 Kultur sonnendurchfluteten Schirmen umspielt von seichter Sommertimehappynessmusik kongruieren mit Theater, Kino, Konzert Veranstaltungen. Der Veranstaltungsplan von 2 8-9 Erzählung Monaten braucht nicht den Platz von einem. Studentische und andere Politik wird an den Nagel gehangen. In den Zeitungsredaktionen macht sich Panik breit: worüber berichten? 10-11 Lies mich! Eine Abhandlung über korrektes Bräunen an der örtlichen Badelache. Gute Tipps für die Sonnenbrandvermeidung in exotischen Ländern, deren Namen man das erste mal im TUI- 12-36 Kult-Uhr Prospekt gelesen hat? Die stehen da ja auch drin. Was kann ein guter Artikel im Sommer leisten? Kann er die Wartezeit bis zum Abflug in den langherbeigebeteten Sommerurlaub 37 Wohnungsbörse verkürzen? Oder kann er die trösten, die wieder zurück gekommen sind. Eingetrudelt im so viel graueren Deutschland. Das so genannte Sommerlochphänomen treib zuweilen 38 Adressen merkwürdige Blüten in der deutschen Zeitungslandschaft. Daheimgebliebene Zeitungsredakteure sehen die vielen leeren Blätter ihrer Zeitung als Chance noch einmal nachdringlich ihre eigenen verloren geglaubten Themen als neu aufzutischen. Wir machen das nicht! Deshalb ist unsere Zeitung etwas dünner, und das Editorial jetzt zu Ende. Die Redaktion und im Netz? www.kultur-cottbus.de Impressum Herausgeber: Redaktion: Robert Amat-Kreft; Diemo Kemmesies; Blattwerk e.V.. Thomas Scheer; Kathleen Priefer; mit Unterstützung: Muggefug e.V. Layout und Edition: Diemo Kemmesies StuRa der BTU Cottbus Fotos Diemo Kemmesies StuPa der FH-Lausitz Anzeigen: Robert Amat-Kreft Glad House Druck: Druck & Satz Großräschen, Auflage: 4000 Studentenwerk Kontakt: Tel: 0355/4948199; StuPit e.V. -

Borderlands E-Journal

borderlands e-journal www.borderlands.net.au VOLUME 11 NUMBER 1, 2012 Missing In Action By all media necessary Suvendrini Perera School of Media, Culture & Creative Arts, Curtin University This essay weaves itself around the figure of the hip-hop artist M.I.A. Its driving questions are about the impossible choices and willed identifications of a dirty war and the forms of media, cultural politics and creativity they engender; their inescapable traces and unaccountable hauntings and returns in diasporic lives. In particular, the essay focuses on M.I.A.’s practice of an embodied poetics that expresses the contradictory affective and political investments, shifting positionalities and conflicting solidarities of diaspora lives enmeshed in war. In 2009, as the military war in Sri Lanka was nearing its grim conclusion, with what we now know was the cold-blooded killing of thousands of Tamil civilians inside an official no-fire zone, entrapped between two forms of deadly violence, a report in the New York Times described Mathangi ‘Maya’ Arulpragasam as the ‘most famous member of the Tamil diaspora’ (Mackey 2009). Mathangi Arulpragasam had become familiar to millions across the globe in her persona as the hip-hop performer M.I.A., for Missing in Action. In the last weeks of the war, she made a number of public appeals on behalf of those trapped by the fighting, including a last-minute tweet to Oprah Winfrey to save the Tamils. Her appeal, which went unheeded, was ill- judged and inspired in equal parts. It suggests the uncertain, precarious terrain that M.I.A. -

2011 – Cincinnati, OH

Society for American Music Thirty-Seventh Annual Conference International Association for the Study of Popular Music, U.S. Branch Time Keeps On Slipping: Popular Music Histories Hosted by the College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza 9–13 March 2011 Cincinnati, Ohio Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the F pioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers.