PDF Transition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amjad Ali Khan & Sharon Isbin

SUMMER 2 0 2 1 Contents 2 Welcome to Caramoor / Letter from the CEO and Chairman 3 Summer 2021 Calendar 8 Eat, Drink, & Listen! 9 Playing to Caramoor’s Strengths by Kathy Schuman 12 Meet Caramoor’s new CEO, Edward J. Lewis III 14 Introducing in“C”, Trimpin’s new sound art sculpture 17 Updating the Rosen House for the 2021 Season by Roanne Wilcox PROGRAM PAGES 20 Highlights from Our Recent Special Events 22 Become a Member 24 Thank You to Our Donors 32 Thank You to Our Volunteers 33 Caramoor Leadership 34 Caramoor Staff Cover Photo: Gabe Palacio ©2021 Caramoor Center for Music & the Arts General Information 914.232.5035 149 Girdle Ridge Road Box Office 914.232.1252 PO Box 816 caramoor.org Katonah, NY 10536 Program Magazine Staff Caramoor Grounds & Performance Photos Laura Schiller, Publications Editor Gabe Palacio Photography, Katonah, NY Adam Neumann, aanstudio.com, Design gabepalacio.com Tahra Delfin,Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Brittany Laughlin, Director of Marketing & Communications Roslyn Wertheimer, Marketing Manager Sean Jones, Marketing Coordinator Caramoor / 1 Dear Friends, It is with great joy and excitement that we welcome you back to Caramoor for our Summer 2021 season. We are so grateful that you have chosen to join us for the return of live concerts as we reopen our Venetian Theater and beautiful grounds to the public. We are thrilled to present a full summer of 35 live in-person performances – seven weeks of the ‘official’ season followed by two post-season concert series. This season we are proud to showcase our commitment to adventurous programming, including two Caramoor-commissioned world premieres, three U.S. -

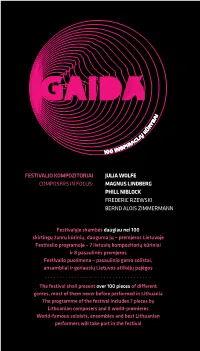

Julia Wolfe Magnus Lindberg Phill Niblock Frederic

FESTIVALIO KOMPOZITORIAI JULIA WOLFE COMPOSERS IN FOCUS: MAGNUS LINDBERG PHILL NIBLOCK FREDERIC RZEWSKI BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN Festivalyje skambės daugiau nei 100 skirtingų žanrų kūrinių, dauguma jų – premjeros Lietuvoje Festivalio programoje – 7 lietuvių kompozitorių kūriniai ir 8 pasaulinės premjeros Festivalio puošmena – pasaulinio garso solistai, ansambliai ir geriausių Lietuvos atlikėjų pajėgos The festival shall present over 100 pieces of different genres, most of them never before performed in Lithuania The programme of the festival includes 7 pieces by Lithuanian composers and 8 world-premieres World-famous soloists, ensembles and best Lithuanian performers will take part in the festival PB 1 PROGRAMA | TURINYS In Focus: Festivalio dėmesys taip pat: 6 JULIA WOLFE 18 FREDERIC RZEWSKI 10 MAGNUS LINDBERG 22 BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN 14 PHILL NIBLOCK 24 Spalio 20 d., šeštadienis, 20 val. 50 Spalio 26 d., penktadienis, 19 val. Vilniaus kongresų rūmai Šiuolaikinio meno centras LAURIE ANDERSON (JAV) SYNAESTHESIS THE LANGUAGE OF THE FUTURE IN FAHRENHEIT Florent Ghys. An Open Cage (2012) 28 Spalio 21 d., sekmadienis, 20 val. Frederic Rzewski. Les Moutons MO muziejus de Panurge (1969) SYNAESTHESIS Meredith Monk. Double Fiesta (1986) IN CELSIUS Julia Wolfe. Stronghold (2008) Panayiotis Kokoras. Conscious Sound (2014) Julia Wolfe. Reeling (2012) Alexander Schubert. Sugar, Maths and Whips Julia Wolfe. Big Beautiful Dark and (2011) Scary (2002) Tomas Kutavičius. Ritus rhythmus (2018, premjera)* 56 Spalio 27 d., šeštadienis, 19 val. Louis Andriessen. Workers Union (1975) Lietuvos nacionalinė filharmonija LIETUVOS NACIONALINIS 36 Spalio 24 d., trečiadienis, 19 val. SIMFONINIS ORKESTRAS Šiuolaikinio meno centras RŪTA RIKTERĖ ir ZBIGNEVAS Styginių kvartetas CHORDOS IBELHAUPTAS (fortepijoninis duetas) Dalyvauja DAUMANTAS KIRILAUSKAS COLIN CURRIE (kūno perkusija, (fortepijonas) Didžioji Britanija) Laurie Anderson. -

Bang on a Can Live – Vol

NWCR646 Bang on a Can Live – Vol. 2 Gary Trosclair, trumpet; Mark Stewart, electric guitar; Alan Moverman, piano and synthesizer; Tigger Benford, percussion Jeffrey Brooks 3. Composition for Two Pianos (1992) ................... (8:55) (Bang on a Can 1992) Piano Duo – Cees van Zeeland & Gerard Bouwhuis Elizabeth Brown 4. Migration – in memory of Julie Farrell (1992) .... (11:44) (Bang on a Can 1992) Elizabeth Brown, shakuhachi; Mayuki Fukuhara, violin; Sarah Clarke, viola; Theodore Mook, cello David Lang 5. The Anvil Chorus (1991) ..................................... (7:00) (Bang on a Can 1991) Steve Schick, percussion Jeffrey Mumford 6. a pond within the drifting dusk (1989) ................ (9:22) (Bang on a Can 1989) Laura Gilbert, alto flute; Joshua Gordon, cello; Victoria Drake, harp Phil Kline Shelley Hirsch/David Weinstein 7. Bachman’s Warbler (1992) ................................. (16:34) 1. Haiku Lingo (excerpt) (1990) ............................. (8:15) (Bang on a Can 1992) Phil Kline, harmonica and (Bang on a Can 1990) Shelley Hirsch, voice; boomboxes David Weinstein, electronics Total playing time: 74:53 Lois V. Vierk 2. Red Shift IV (1991) ............................................. (12:25) Ê & © 1993 Composers Recordings, Inc. (Bang on a Can 1991) A Cloud Nine Consort: © 2007 Anthology of Recorded Music, Inc. Notes Bang on a Can is among the most inclusive and hospitable of introductions are cursory, a bit nervous and wonderfully all new music festivals. Its ambiance is informal. When the illuminating—an introduction to the person, not the concept, venues allow it, audiences can come and go during annual all- behind the music. When John Cage stepped on stage to kick day marathon concerts, sit up close and listen, or casually off the 1992 edition of the festival, which began with his stand in the back with a beer or an apple cider. -

First Glimpse 2018: Songs from the Great Room

presents First Glimpse 2018: Songs from the Great Room World Premiere Songs rom e 17-19 omosers e oie series Composers & the Voice Artistic Director - Steven Osgood Musical Direction by Mila Henry & Kelly Horsted 2017-19 Composers & the Voice Composer and Librettist Fellows Laura Barati Pamela Stein Lynde Sokunthary Svay Matthew Browne Scott Ordway Amber Vistein Kimberly Davies Frances Pollock Alex Weiser 2017-18 Composers & the Voice Resident Singers Tookah Sapper, soprano Jennifer Goode Cooper, soprano Blythe Gaissert, mezzo-soprano* Blake Friedman, tenor Mario Diaz Moresco, baritone Adrian Rosas, bass-baritone *Songs written for mezzo-soprano will be performed tonight by Kate Maroney Resident Stage Manager - W. Wilson Jones May 19 & 20, 2018 - 7:30 PM SOUTH OXFORD SPACE, BROOKLYN FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR I always have mixed emotions when a cycle of Composers and the Voice arrives at the First Glimpse concerts. It is thrilling to FINALLY throw open the doors of this room and share some of the wonderful pieces that have been written since last Fall. But it also means that my time working so regularly and directly with a family of artists is drawing to a close. It takes a huge team of people to make a program like Composers and the Voice work, but I would like to thank two who have stepped into new and significantly larger roles this year. Mila Henry, C&V Head of Music, has overseen the musical organization of the entire season, while also preparing several pieces for each of our workshop sessions. Matt Gray, as C&V Head of Drama, has brought his insight into character and operatic narrative into every element of the program. -

Presidency Cultural Programme in Kraków

Presidency Cultural Programme in Kraków 2011-08-23 4th “Divine Comedy” International Theatre Festival December 2011 The Divine Comedy festival is not just a competition, but also an opportunity to see the top shows by young Polish directors and the chance to compare opinions of Polish theatre with critics from all over Europe. The selection of productions is made by the most prominent Polish critics, journalists, and reviewers, while the decision on who walks away with the figurine of the Divine Comedian is made by an independent international jury. The festival is divided into three blocks. In the Inferno section – the contest for the best Polish productions of the previous season – the maestros of Polish theatre and their students compete for the award. Paradiso is the section of the festival devoted to the work of young, but already acclaimed, directors. The Purgatorio block includes accompanying events. It should be emphasised that this year the festival has changed its formula – traditionally the competition section and culmination of accompanying events fall in December, while the international section takes place all year round – every month excluding the summer holidays. Organiser: Krakow Festival Office www.boskakomedia.pl Opera Rara: A. Vivaldi – L’Oracolo in Messenia 8 December 2011 December’s performance in the Opera Rara cycle perfectly achieves the goals set by originator Filip Berkowicz when he began the project in 2009 – to present above all works which are rarely played or which have been restored to the repertoire after centuries of absence in concert halls. This will be the world première of the opera written by Antonio Vivaldi in the last years of his life, published just after his death and then lost for a very long time. -

Eric Singer: Road Warrior

EXCLUSIVE! KISS DRUMMERS TIMELINE KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISSTHE WORLD’SKISS KISS #1 DRUMKISS RESOURCEKISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS ERICKISS KISS KISSSINGER: KISS KISS KISS ROADKISS KISS KISS WARRIOR KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS2020 KISS KISSMD KISS READERS KISS KISS KISS KISSPOLL KISS KISS KISS KISS KISSSS KISSKIS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISSSS KISSKIS KISS KISS KISSBALLOT’S KISS KISS KISS KISSOPEN! KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISSSS KISS KIS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISSREMO KISS SUBKISS MUFF’LKISS KISS REVIEWED KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISSJANUARY KISS 2020 KISS KISS2019 KISS CHICAGO KISS KISS DRUM KISS KISS SHOW KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISSCREATIVE KISS KISS PRACTICE KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISSSTANTON KISS KISS MOORE KISS KISS GEARS KISS UPKISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS KISS What’s Old is New Again. -

Transizioni E Dissoluzioni Di Fine Anno Electroshitfing

SENTIREASCOLTARE online music magazine GENNAIO N. 27 The Shins 2006: transizioni e dissoluzioni di fine anno Electroshitfing Fabio Orsi Alessandro Raina Coaxial Jessica Bailiff Larkin Grimm The Low Lows Deerhunter Cul De Sac The Long Blondess e n tTerry i r e a s c o lRiley t a r e sommario 4 News 8 The Lights On The Low Lows, Coaxial, Larkin Grimm, Deerhunter 8 2 Speciali The Long Blondes, Alessandro Raina, Jessica Bailiff, Fabio Orsi, Electroshifting, The Shins, Il nostro 2006 9 Recensioni Arbouretum, Of Montreal, Tin Hat, James Holden, Lee Hazlewood, Ronin, The Earlies, Ghost, Field Music, Hella, Giardini Di Mirò, Mira Calix, Deerhoof... 8 Rubriche (Gi)Ant Steps Miles Davis We Are Demo Classic Ultravox!, Cul De Sac Cinema Cult: Angel Heart Visioni: A Scanner Darkly, Marie Antoinette, Flags Of Our Fathers… 2 I cosiddetti contemporanei Igor Stravinskij Direttore Edoardo Bridda Coordinamento Antonio Puglia 9 Consulenti alla redazione Daniele Follero Stefano Solventi Staff Valentina Cassano Antonello Comunale Teresa Greco Hanno collaborato Gianni Avella, Gaspare Caliri, Andrea Erra, Paolo Grava, Manfredi Lamartina, Andrea Monaco, Massimo Padalino, Stefano Pifferi, Stefano Renzi, Costanza Salvi, Vincenzo Santarcangelo, Alfonso Tramontano Guerritore, Giancarlo Turra, Fabrizio Zampighi, Giusep- pe Zucco Guida spirituale Adriano Trauber (1966-2004) Grafica Paola Squizzato, Squp, Edoardo Bridda 94 in copertina The Shins SentireAscoltare online music magazine Registrazione Trib.BO N° 7590 del 28/10/05 Editore Edoardo Bridda Direttore responsabile Ivano Rebustini Provider NGI S.p.A. Copyright © 2007 Edoardo Bridda. Tutti i diritti riservati. s e n t i r e a s c o l t a r e La riproduzione totale o parziale, in qualsiasi forma, su qualsiasi supporto e con qualsiasi mezzo, è proibita senza autorizzazione scritta di SentireAscoltare news a cura di Teresa Greco E’ morto “Mr. -

Donnacha Dennehy's Riveting New Opera, the Hunger Featuring Alarm

Donnacha Dennehy’s riveting new opera, The Hunger featuring Alarm Will Sound premieres at BAM, Sep 30 & Oct 1 Spellbinding soprano Katherine Manley makes her New York debut Bloomberg Philanthropies is the Season Sponsor. The Hunger By Donnacha Dennehy Alarm Will Sound Conducted by Alan Pierson Directed by Tom Creed Presented in association with Irish Arts Center Set and video design by Jim Findlay BAM Howard Gilman Opera House (30 Lafayette Ave) Sep 30 & Oct 1 at 7:30pm Tickets start at $20 Talk: Understanding The Hunger Co-presented by BAM and Irish Arts Center With Tom Creed, Maureen O. Murphy, Donnacha Dennehy, and other panelists to be announced Oct 1 at 4:30pm Irish Arts Center (553 West 51st Street) Free with RSVP More information at irishartscenter.org Sep 1, 2016/Brooklyn, NY—Rooted in the emotional, political, and socioeconomic devastation of Ireland’s Great Famine (1845-52), The Hunger is a powerful new opera by renowned contemporary composer Donnacha Dennehy, making its New York premiere at BAM on September 30 and October 1. Performed by the chamber band Alarm Will Sound, soprano Katherine Manley, and legendary sean nós singer Iarla Ó Lionáird, the libretto principally draws from rare, first-hand accounts by Asenath Nicholson, an American humanitarian so moved by the waves of immigrants arriving in New York that she travelled to Ireland to bear witness, reporting from the cabins of starving families. By integrating historical and new documentary material, the opera provides a unique perspective on a period of major upheaval during which at least one million people died, and another million emigrated—mainly to the US, Canada, and the UK—forever altering the social fabric. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. ORCID: 0000-0002-0047-9379 (2021). New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices. In: McPherson, G and Davidson, J (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/25924/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices Ian Pace For publication in Gary McPherson and Jane Davidson (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), chapter 17. Introduction At the beginning of the twentieth century concert programming had transitioned away from the mid-eighteenth century norm of varied repertoire by (mostly) living composers to become weighted more heavily towards a historical and canonical repertoire of (mostly) dead composers (Weber, 2008). -

Fischerspooner Bio

FISCHERSPOONER BIO Joe Gillis: I didn't know you were planning a comeback. Norma Desmond: I hate that word. It's a return, a return to the millions of people who have never forgiven me for deserting the screen. -Sunset Boulevard It was supposed to be just one song. In January, 2013, four years after the release of their previous album, Entertainment , Warren Fischer invited Casey Spooner into the studio to collaborate on their first new song since 2008. If you know anything about Fischerspooner–a DIY art project that debuted with a guerrilla performance at a Manhattan Starbucks and snowballed into a sprawling spectacle that kicked open the door for the post-electroclash pop revolution–you know that once they get working, even their most modest plans have a way of quickly turning into something much grander. Four years and some change later, Fischerspooner is back with what might be their most ambitious and challenging project yet: an expansive multimedia work spanning a museum exhibition, an art book, and Sir, their first collection of new music in nearly a decade. Fischerspooner has never just been the work of Fischer and Spooner. For each project the pair have built a family of collaborators to help realize their vision. Well after it became clear that their new project wasn’t going to stop at just one song, Spooner turned to his longtime friend Michael Stipe for songwriting advice. In typical Fischerspooner style, asking for notes on one track quickly turned into a full-fledged collaboration. Soon enough, Stipe had signed on to co-write and produce the album, and Spooner was working round-the-clock sessions in a studio around the corner from Stipe’s home in Athens, Georgia– a place he had first visited 30 years ago after the pair hit it off on the dance floor of Athens’ 40 Watt Club, and an 18 year old virgin with a Prince Valiant haircut found himself going home with a long-haired rock star in BMX pants 10 years his senior. -

1 Loghaven Artist Residency Launches with Announcement Of

Loghaven Artist Residency Launches with Announcement of Inaugural Artists and Completion of 90-Acre Campus First Artists in Residence Include Ann Carlson, Amy Lam, Jennifer Wen Ma, Daniel Bernard Roumain, Wendy Red Star, and Many Others Loghaven Facilities Include Purpose-Built Studios, New Equipment, and Artist Housing in Rehabilitated, Historic Log Cabins Open Call for Applications for 2021 Residencies to Begin June 1, 2020 Knoxville, TN – January 22, 2020 – Loghaven Artist Residency, a newly created residency for emerging and established artists in the fields of visual art, dance, music, writing, theater, and interdisciplinary work, announces its first group of artists and the completion of its campus. The launch of Loghaven Artist Residency is the culmination of years of planning, research, design, and input from artists, arts leaders, and the Alliance of Artist Communities. The residency features artist housing in historic, rehabilitated log cabins, as well as a newly constructed Performing Arts Studio and Visual Arts Studio, and a 3,900-square-foot Gateway Building with additional studio space and facilities for artists—all located on 90 acres of woodland, minutes from downtown Knoxville, Tennessee. Loghaven Artist Residency offers: • Facilities for dancers and theater makers—there are limited residencies that offer dancers and theater makers the facilities that are essential for their work. Loghaven has a professionally designed Performing Arts Studio and a Multidisciplinary Studio to support these practitioners. • Spaces for collaborative artist groups—the number of artists working collaboratively has grown significantly, and few residences are designed to accommodate this type of practice. Loghaven’s studio spaces serve the needs of collaborative teams: all are large enough for group work, and three of the artist cabins are suited for an intensive live/work experience for a collaborative team. -

2011 – Cincinnati, OH

Society for American Music Thirty-Seventh Annual Conference International Association for the Study of Popular Music, U.S. Branch Time Keeps On Slipping: Popular Music Histories Hosted by the College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza 9–13 March 2011 Cincinnati, Ohio Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the F pioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers.