English Language Learners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Language: Did You Know?

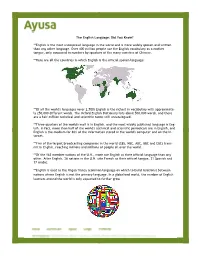

The English Language: Did You Know? **English is the most widespread language in the world and is more widely spoken and written than any other language. Over 400 million people use the English vocabulary as a mother tongue, only surpassed in numbers by speakers of the many varieties of Chinese. **Here are all the countries in which English is the official spoken language: **Of all the world's languages (over 2,700) English is the richest in vocabulary with approximate- ly 250,000 different words. The Oxford English Dictionary lists about 500,000 words, and there are a half-million technical and scientific terms still uncatalogued. **Three-quarters of the world's mail is in English, and the most widely published language is Eng- lish. In fact, more than half of the world's technical and scientific periodicals are in English, and English is the medium for 80% of the information stored in the world's computer and on the In- ternet. **Five of the largest broadcasting companies in the world (CBS, NBC, ABC, BBC and CBC) trans- mit in English, reaching millions and millions of people all over the world. **Of the 163 member nations of the U.N., more use English as their official language than any other. After English, 26 nations in the U.N. cite French as their official tongue, 21 Spanish and 17 Arabic. **English is used as the lingua franca (common language on which to build relations) between nations where English is not the primary language. In a globalized world, the number of English learners around the world is only expected to further grow. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jana Krejčířová Australian English Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph. D. 2016 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph.D. for her patience and valuable advice. I would also like to thank my partner Martin Burian and my family for their support and understanding. Table of Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................... 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 7 1. AUSTRALIA AND ITS HISTORY ................................................................. 10 1.1. Australia before the arrival of the British .................................................... 11 1.1.1. Aboriginal people .............................................................................. 11 1.1.2. First explorers .................................................................................... 14 1.2. Arrival of the British .................................................................................... 14 1.2.1. Convicts ............................................................................................. 15 1.3. Australia in the -

German and English Noun Phrases

RICE UNIVERSITY German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach Ward Keith Barrows A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF 3 1272 00675 0689 Master of Arts Thesis Directors signature: / Houston, Texas April, 1971 Abstract: German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach, by Ward Keith Barrows The paper presents a contrastive approach to German and English based on the theory of transformational grammar. In the first chapter, contrastive analysis is discussed in the context of foreign language teaching. It is indicated that contrastive analysis in pedagogy is directed toward the identification of sources of interference for students of foreign languages. It is also pointed out that some differences between two languages will prove more troublesome to the student than others. The second chapter presents transformational grammar as a theory of language. Basic assumptions and concepts are discussed, among them the central dichotomy of competence vs performance. Chapter three then present the structure of a grammar written in accordance with these assumptions and concepts. The universal base hypothesis is presented and adopted. An innovation is made in the componential structire of a transformational grammar: a lexical component is created, whereas the lexicon has previously been considered as part of the base. Chapter four presents an illustration of how transformational grammars may be used contrastively. After a base is presented for English and German, lexical components and some transformational rules are contrasted. The final chapter returns to contrastive analysis, but discusses it this time from the point of view of linguistic typology in general. -

New Zealand English

New Zealand English Štajner, Renata Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2011 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:005306 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-26 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Preddiplomski studij Engleskog jezika i književnosti i Njemačkog jezika i književnosti Renata Štajner New Zealand English Završni rad Prof. dr. sc. Mario Brdar Osijek, 2011 0 Summary ....................................................................................................................................2 Introduction................................................................................................................................4 1. History and Origin of New Zealand English…………………………………………..5 2. New Zealand English vs. British and American English ………………………….….6 3. New Zealand English vs. Australian English………………………………………….8 4. Distinctive Pronunciation………………………………………………………………9 5. Morphology and Grammar……………………………………………………………11 6. Maori influence……………………………………………………………………….12 6.1.The Maori language……………………………………………………………...12 6.2.Maori Influence on the New Zealand English………………………….………..13 6.3.The -

English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate

ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 First published in 1993 by Rhodes University Grahamstown South Africa ©PROF LS WRIGHT -1993 Laurence Wright English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate ISBN: 0-620-03155-7 No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Mr Vice Chancellor, my former teachers, colleagues, ladies and gentlemen: It is a special privilege to be asked to give an inaugural lecture before the University in which my undergraduate days were spent and which holds, as a result, a special place in my affections. At his own "Inaugural Address at Edinburgh" in 1866, Thomas Carlyle observed that "the true University of our days is a Collection of Books".1 This definition - beloved of university library committees worldwide - retains a certain validity even in these days of microfiche and e-mail, but it has never been remotely adequate. John Henry Newman supplied the counterpoise: . no book can convey the special spirit and delicate peculiarities of its subject with that rapidity and certainty which attend on the sympathy of mind with mind, through the eyes, the look, the accent and the manner. -

New Zealand Ways of Speaking English Edited by Allan Bell and Janet Holmes

UCLA Issues in Applied Linguistics Title New Zealand Ways of Speaking English edited by Allan Bell and Janet Holmes. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters, 1990. 305 pp. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/77n0788f Journal Issues in Applied Linguistics, 2(1) ISSN 1050-4273 Author Locker, Rachel Publication Date 1991-06-30 DOI 10.5070/L421005133 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California REVIEWS New Zealand Ways of Speaking English edited by Allan Bell and Janet Holmes. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters, 1990. 305 pp. Reviewed by Rachel Locker University of California, Los Angeles Coming to America has resulted in an interesting encounter with my linguistic identity, my New Zealand accent regularly provoking at least two distinct reactions: either "Please say something, I love the way you talk!" (which causes me some amusement but mainly disbelief), or "Your English is very good- what's your native language?" It is difficult to review a book like New Zealand Ways of Speaking English without relating such experiences, because as a nation New Zealanders at home and abroad have long suffered from a lurking sense of inferiority about the way they speak English, especially compared with those in the colonial "homeland," i.e., England. That dialectal differences create attitudes about what is better and worse is no news to scholars of language use, but this collection of studies on New Zealand English (NZE) not only reveals some interesting peculiarities of that particular dialect and its speakers from "down- under"; it also makes accessible the significant contributions of New Zealand linguists to broader theoretical concerns in sociolinguistics and applied linguistics. -

Afrikaans FAMILY HISTORY LIBRARY" SALTLAKECITY, UTAH TMECHURCHOF JESUS CHRISTOF Latl'er-Qt.Y SAINTS

GENEALOGICAL WORD LIST ~ Afrikaans FAMILY HISTORY LIBRARY" SALTLAKECITY, UTAH TMECHURCHOF JESUS CHRISTOF LATl'ER-Qt.y SAINTS This list contains Afrikaans words with their English these compound words are included in this list. You translations. The words included here are those that will need to look up each part of the word separately. you are likely to find in genealogical sources. If the For example, Geboortedag is a combination of two word you are looking for is not on this list, please words, Geboorte (birth) and Dag (day). consult a Afrikaans-English dictionary. (See the "Additional Resources" section below.) Alphabetical Order Afrikaans is a Germanic language derived from Written Afrikaans uses a basic English alphabet several European languages, primarily Dutch. Many order. Most Afrikaans dictionaries and indexes as of the words resemble Dutch, Flemish, and German well as the Family History Library Catalog..... use the words. Consequently, the German Genealogical following alphabetical order: Word List (34067) and Dutch Genealogical Word List (31030) may also be useful to you. Some a b c* d e f g h i j k l m n Afrikaans records contain Latin words. See the opqrstuvwxyz Latin Genealogical Word List (34077). *The letter c was used in place-names and personal Afrikaans is spoken in South Africa and Namibia and names but not in general Afrikaans words until 1985. by many families who live in other countries in eastern and southern Africa, especially in Zimbabwe. Most The letters e, e, and 0 are also used in some early South African records are written in Dutch, while Afrikaans words. -

Introduction to the History of the English Language

INTRODUCTION TO THE HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE Written by László Kristó 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 4 NOTES ON PHONETIC SYMBOLS USED IN THIS BOOK ................................................. 5 1 Language change and historical linguistics ............................................................................. 6 1.1 Language history and its study ......................................................................................... 6 1.2 Internal and external history ............................................................................................. 6 1.3 The periodization of the history of languages .................................................................. 7 1.4 The chief types of linguistic change at various levels ...................................................... 8 1.4.1 Lexical change ........................................................................................................... 9 1.4.2 Semantic change ...................................................................................................... 11 1.4.3 Morphological change ............................................................................................. 11 1.4.4 Syntactic change ...................................................................................................... 12 1.4.5 Phonological change .............................................................................................. -

Of Languages

INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION RESEARCH FOUNDATION ® Index of Languages Français Türkçe 日本語 English Pусский Nederlands Português中文Español Af-Soomaali Deutsch Tiếng Việt Bahasa Melayu Ελληνικά Kiswahili INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION RESEARCH FOUNDATION ® P.O. Box 3665 Culver City, CA 90231-3665 Phone: 310.258.9451 Fax: 310.342.7086 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ierf.org 1969-2017 © 2017 International Education Research Foundation (IERF) Celebrating 48 years of service Index of Languages IERF is pleased to present the Index of Languages as the newest addition to The New Country Index series. as established as a not-for-profit, public-benefit agency This helpful guide provides the primary languages of instruction for over 200 countries and territories around but also in the world. Inez Sepmeyer and the world. It highlights not only the medium of instruction at the secondary and postsecondary levels, but also , respectively, identifies the official language(s) of these regions. This resource, compiled by IERF evaluators, was developed recognized the need for assistance in the placement of international students and professionals. In 1969, IERF as a response to the requests that we receive from many of our institutional users. These include admissions officers, registrars and counselors. A bonus section has also been added to highlight the examinations available to help assess English language proficiency. Using ation of individuals educated I would like to acknowledge and thank those IERF evaluators who contributed to this publication. My sincere . gratitude also goes to the editors for their hard work, energy and enthusiasm that have guided this project. Editors: Emily Tse Alice Tang profiles of 70 countries around the Contributors: Volume I. -

Why Idioms Are Important for English Language Learners

180 Матеріали міжнародної наукової конференції Jacqueline Ambrose Mikolaiv State Pedagogical University WHY IDIOMS ARE IMPORTANT FOR ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS The English language has more than 1,000,000 words and is one of the most flexible languages in the world. It’s a living language, like those other languages we use today. Understanding the lexicon of English demands more than knowing the denotative meaning of words. It requires its speakers to have connotative word comprehension and more, an understanding of figurative language. Idioms fall into this final category. The focus of this paper is to share the importance of idioms for non-native speakers as part of their mastery of the English language. Idioms share cultural and historical information and broadens people’s understanding and manipulation of a language. Among the various definitions of idioms are: (1) the language peculiar to a people, country, class, community or, more rarely, an individual; (2) a construction or expression having a meaning different from the literal one or not according to the usual patterns of the language (New Webster’s Dictionary, 1993). It is the second definition that best suits the focus of this paper. Idioms include all the expressions we use that are unique to English, including cliches and slang. Prepositional usage is also a common part of idiomatic expressons (Princeton Review, 1998), but this paper addresses idioms as used in figurative language. The following sentence contains two idioms: Carol’s father was going to see red is she failed tomorrow’s exam. She was burning the midnight oil because she hadn’t been taking her school work seriously. -

History of English Language (Eng1c03)

School of Distance Education HISTORY OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE (ENG1C03) STUDY MATERIAL I SEMESTER CORE COURSE MA ENGLISH (2019 Admission ONWARDS) UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION Calicut University P.O, Malappuram Kerala, India 673 635. 190003 History of English Language Page 1 School of Distance Education UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION STUDY MATERIAL FIRST SEMESTER MA ENGLISH (2019 ADMISSION) CORE COURSE : ENG1C03 : HISTORY OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE Prepared by : 1. Smt.Smitha N, Assistant Professor on Contract (English) School of Distance Education, University of Calicut. 2. Prof. P P John (Retd.), St.Joseph’s College, Devagiri. Scrutinized by : Dr.Aparna Ashok, Assistant Professor on Contract, Dept. of English, University of Calicut. History of English Language Page 2 School of Distance Education CONTENTS 1 Section : A 6 2 Section : B 45 3 Section : C 58 History of English Language Page 3 School of Distance Education Introduction As English Literature learners, we must know the evolution of this language over the past fifteen hundred years or more. This course offers an overview of the History of English Language from its origin to the present. This SLM will have three sections: Section A briefly considers the early development of English Language and major historical events that had been made changes in its course. Section B takes up the changes that have taken place in English through Foreign invasions in 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, besides it discusses the contribution of major writers to enrich this language. In the Section C, we trace out the evolution of standard English and the significance of English in this globalized world where technology reigns. -

German Videos - (Last Update December 5, 2019) Use the Find Function to Search This List

German Videos - (last update December 5, 2019) Use the Find function to search this list Aguirre, The Wrath of God Director: Werner Herzog with Klaus Kinski. 1972, 94 minutes, German with English subtitles. A band of Spanish conquistadors travels into the Amazon jungle searching for the legendary city of El Dorado, but their leader’s obsessions soon turn to madness.LLC Library CALL NO. GR 009 Aimée and Jaguar DVD CALL NO. GR 132 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul Director: Rainer Werner Fassbinder. with Brigitte Mira, El Edi Ben Salem. 1974, 94 minutes, German with English subtitles. A widowed German cleaning lady in her 60s, over the objections of her friends and family, marries an Arab mechanic half her age in this engrossing drama. LLC Library CALL NO. GR 077 All Quiet on the Western Front DVD CALL NO. GR 134 A/B Alles Gute (chapters 1 – 4) CALL NO. GR 034-1 Alles Gute (chapters 13 – 16) CALL NO. GR 034-4 Alles Gute (chapters 17 – 20) CALL NO. GR 034-5 Alles Gute (chapters 21 – 24) CALL NO. GR 034-6 Alles Gute (chapters 25 – 26) CALL NO. GR 034-7 Alles Gute (chapters 9 – 12) CALL NO. GR 034-3 Alpen – see Berlin see Berlin Deutsche Welle – Schauplatz Deutschland, 10-08-91. [ Opening missing ], German with English subtitles. LLC Library Alpine Austria – The Power of Tradition LLC Library CALL NO. GR 044 Amerikaner, Ein – see Was heißt heir Deutsch? LLC Library Annette von Droste-Hülshoff CALL NO. GR 120 Art of the Middle Ages 1992 Studio Quart, about 30 minutes.