The Labyrinth and the Green Man

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HOMERIC-ILIAD.Pdf

Homeric Iliad Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power Contents Rhapsody 1 Rhapsody 2 Rhapsody 3 Rhapsody 4 Rhapsody 5 Rhapsody 6 Rhapsody 7 Rhapsody 8 Rhapsody 9 Rhapsody 10 Rhapsody 11 Rhapsody 12 Rhapsody 13 Rhapsody 14 Rhapsody 15 Rhapsody 16 Rhapsody 17 Rhapsody 18 Rhapsody 19 Rhapsody 20 Rhapsody 21 Rhapsody 22 Rhapsody 23 Rhapsody 24 Homeric Iliad Rhapsody 1 Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power [1] Anger [mēnis], goddess, sing it, of Achilles, son of Peleus— 2 disastrous [oulomenē] anger that made countless pains [algea] for the Achaeans, 3 and many steadfast lives [psūkhai] it drove down to Hādēs, 4 heroes’ lives, but their bodies it made prizes for dogs [5] and for all birds, and the Will of Zeus was reaching its fulfillment [telos]— 6 sing starting from the point where the two—I now see it—first had a falling out, engaging in strife [eris], 7 I mean, [Agamemnon] the son of Atreus, lord of men, and radiant Achilles. 8 So, which one of the gods was it who impelled the two to fight with each other in strife [eris]? 9 It was [Apollo] the son of Leto and of Zeus. For he [= Apollo], infuriated at the king [= Agamemnon], [10] caused an evil disease to arise throughout the mass of warriors, and the people were getting destroyed, because the son of Atreus had dishonored Khrysēs his priest. Now Khrysēs had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom [apoina]: moreover he bore in his hand the scepter of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant’s wreath [15] and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

Fantasy Illustration As an Expression of Postmodern 'Primitivism': the Green Man and the Forest Emily Tolson

Fantasy Illustration as an Expression of Postmodern 'Primitivism': The Green Man and the Forest Emily Tolson , Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: Lize Van Robbroeck Co-Supervisor: Paddy Bouma April 2006 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Dedaratfton:n I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any Date o~/o?,}01> 11 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Albs tract This study demonstrates that Fantasy in general, and the Green Man in particular, is a postmodern manifestation of a long tradition of modernity critique. The first chapter focuses on outlining the history of 'primitivist' thought in the West, while Chapter Two discusses the implications of Fantasy as postmodern 'primitivism', with a brief discussion of examples. Chapter Three provides an in-depth look at the Green Man as an example of Fantasy as postmodern 'primitivism'. The fmal chapter further explores the invented tradition of the Green Man within the context of New Age spirituality and religion. The study aims to demonstrate that, like the Romantic counterculture that preceded it, Fantasy is a revolt against increased secularisation, industrialisation and nihilism. The discussion argues that in postmodernism the Wilderness (in the form of the forest) is embraced through the iconography of the Green Man. The Green Man is a pre-Christian symbol found carved in wood and stone, in temples and churches and on graves throughout Europe, but his origins and original meaning are unknown, and remain a controversial topic. -

2 Tales of the Gnomes 4 3 3

Clarinet in Eb Tales of the Gnomes for clarinet quartet / choir WernerDeBleser 1. Blue Cap q=56 2 # #4 œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ & # 4 œ œ œ œ œ œ œ™ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ mp J f 8 4 # # œ œ œ œ œ & # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ f 14 rit. œ™ œ # # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ & # J ∑ dim. p 2. Korrigan q=120 # #3 . œ . & # 4 œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ Œ f . 5 # # . œ . 3 # œ œ. œ. œ œ œ œ œ. œ. œ œ œ Œ & . œ. œ ˙ 12 3 # # . œ . & # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ Œ f . 19 # # . œ . # œ œ. œ. œ œ œ œ œ. œ. œ œ œ Œ & . œ. nœ ˙ 3. Green Man =52 q 4 ##4 & 4 ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ pœ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ p 9 4 ## œ & œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ w p œ ˙ 2 Tales of the Gnomes - Clarinet in Eb 4. Trow q=120 2 6 #2 œ œ œ & 4 œ Œ œ œ œ œ œ f mf p. 13 # . 8 & œ œ œ œ œ œ œ. œ œ œ œ œ. œ œ mf . œ œ . p 27 # œ- œ œ - œ - - & œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ f - - 33 # - œ œ œ œ œ & œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ 40 # 8 œ & œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ ˙ ™ œ ˙ p f J 55 # j j œ œ œ œ œ œ œ & œ™ œ ˙ œ™ œ œ œ œ œ œ Œ ˙ ™ J f 5. -

OPELIKA Pride In

ALABAMA POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE. VOL. IX. AVBVRN, ALABAMA, WEDNESDAY. JANVARY 28.1903. NO. 6. Pianoforte Lecture-Recita.1. as a lecture or a concert the en- A SILVER ANNIVERSARY Booming the Annual. The Way to Get is to Give. On Saturday, Jan. 24, Mr. Ed- tertainment would be a success At a meeting of the Glomerata and the combination is truly a Mr. R. W. Burton Celebrates 25th "This is a mighty busy world. ward Baxter Perry, the distin- Bu;ird last Wednesday night it happy idea of Mr. Perry's which Birthday of His Bookstore. We all have to be fed and clothed, guished blkid pianist, gave a was indeed gratifying as well as Probably the moat unique af- and to have warm beds and books recital in Langdon Hall to a was originated by him. encouraging to note the great en- fair in the history of our town and all that. All these things large and appreciative audience. From every point of view the thusiasm manifested in making was the celebration by Mr. R. W. come by labor of some one." said No attraction that has been to recital was a finished perform- preparations and arranging per- Burton, on Friday last, of the Joseph E. Wing to a class of Auburn for some time has been ance—artistic, enjoyable and manent plans for the publication twenty-fifth anniversary of the Ohio school boys. "It happens more enjoyed than was this beneficial—and everyone" who of the Glomerata of "'03." At establishment of his bookstore that this is not a misfortune, .concert, ,.._. -

The Cyclops in the Odyssey, Ulysses, and Asterios Polyp: How Allusions Affect Modern Narratives and Their Hypotexts

THE CYCLOPS IN THE ODYSSEY, ULYSSES, AND ASTERIOS POLYP: HOW ALLUSIONS AFFECT MODERN NARRATIVES AND THEIR HYPOTEXTS by DELLEN N. MILLER A THESIS Presented to the Department of English and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts December 2016 An Abstract of the Thesis of Dellen N. Miller for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of English to be taken December 2016 Title: The Cyclops in The Odyssey, Ulysses, and Asterios Polyp: How Allusions Affect Modern Narratives and Their Hypotexts Approved: _________________________________________ Paul Peppis The Odyssey circulates throughout Western society due to its foundation of Western literature. The epic poem thrives not only through new editions and translations but also through allusions from other works. Texts incorporate allusions to add meaning to modern narratives, but allusions also complicate the original text. By tying two stories together, allusion preserves historical works and places them in conversation with modern literature. Ulysses and Asterios Polyp demonstrate the prevalence of allusions in books and comic books. Through allusions to both Polyphemus and Odysseus, Joyce and Mazzucchelli provide new ways to read both their characters and the ancient Greek characters they allude to. ii Acknowledgements I would like to sincerely thank Professors Peppis, Fickle, and Bishop for your wonderful insight and assistance with my thesis. Thank you for your engaging courses and enthusiastic approaches to close reading literature and graphic literature. I am honored that I may discuss Ulysses and Asterios Polyp under the close reading practices you helped me develop. -

Uncle Bernac a Memory of the Empire Chapter I The

UNCLE BERNAC A MEMORY OF THE EMPIRE CHAPTER I THE COAST OF FRANCE I dare say that I had already read my uncle's letter a hundred times, and I am sure that I knew it by heart. None the less I took it out of my pocket, and, sitting on the side of the lugger, I went over it again with as much attention as if it were for the first time. It was written in a prim, angular hand, such as one might expect from a man who had begun life as a village attorney, and it was addressed to Louis de Laval, to the care of William Hargreaves, of the Green Man in Ashford, Kent. The landlord had many a hogshead of untaxed French brandy from the Normandy coast, and the letter had found its way by the same hands. 'My dear nephew Louis,' said the letter, 'now that your father is dead, and that you are alone in the world, I am sure that you will not wish to carry on the feud which has existed between the two halves of the family. At the time of the troubles your father was drawn towards the side of the King, and I towards that of the people, and it ended, as you know, by his having to fly from the country, and by my becoming the possessor of the estates of Grosbois. No doubt it is very hard that you should find yourself in a different position to your ancestors, but I am sure that you would rather that the land should be held by a Bernac than by a stranger. -

The Helmholtz, the Doctor, the Minotaur, and the Labyrinth

Volume 34 Number 2 Article 7 4-15-2016 The Helmholtz, the Doctor, the Minotaur, and the Labyrinth Buket Akgün Istanbul University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Akgün, Buket (2016) "The Helmholtz, the Doctor, the Minotaur, and the Labyrinth," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 34 : No. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol34/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Compares the use and resolution of Minotaur and Labyrinth themes and imagery, and the identification of the Theseus hero-figure with the monster, in Victor Pelevin’s novel The Helmet of Horror and the sixth season Doctor Who episode “The God Complex.” Additional Keywords Doctor Who (television show); Labyrinths in literature; Minotaur (Greek myth); Pelevin, Victor. -

The Thebaid Europa, Cadmus and the Birth of Dionysus

The Thebaid Europa, Cadmus and the birth of Dionysus Caesar van Everdingen. Rape of Europa. 1650 Zeus = Io Memphis = Epaphus Poseidon = Libya Lysianassa Belus Agenor = Telephassa In the Danaid, we followed the descendants of Belus. The Thebaid follows the descendants of Agenor Agenor = Telephassa Cadmus Phoenix Cylix Thasus Phineus Europa • Agenor migrated to the Levant and founded Sidon • But see Josephus, Jewish Antiquities i.130 - 139 • “… for Syria borders on Egypt, and the Phoenicians, to whom Sidon belongs, dwell in Syria.” (Hdt. ii.116.6) The Levant Levant • Jericho (9000 BC) • Damascus (8000) • Biblos (7000) • Sidon (4000) Biblos Damascus Sidon Tyre Jericho Levant • Canaanites: • Aramaeans • Language, not race. • Moved to the Levant ca. 1400-1200 BC • Phoenician = • purple dye people Biblos Damascus Sidon Tyre Agenor = Telephassa Cadmus Phoenix Cylix Thasus Phineus Europa • Zeus appeared to Europa as a bull and carried her to Crete. • Agenor sent his sons in search of Europa • Don’t come home without her! • The Rape of Europa • Maren de Vos • 1590 Bilbao Fine Arts Museum (Spain) Image courtesy of wikimedia • Rape of Europa • Caesar van Everdingen • 1650 • Image courtesy of wikimedia • Europe Group • Albert Memorial • London, 1872. • A memorial for Albert, husband of Queen Victoria. Crete Europa = Zeus Minos Sarpedon Rhadamanthus • Asterius, king of Crete, married Europa • Minos became king of Crete • Sarpedon king of Lycia • Rhadamanthus king of Boeotia The Brothers of Europa • Phoenix • Remained in Phoenicia • Cylix • Founded -

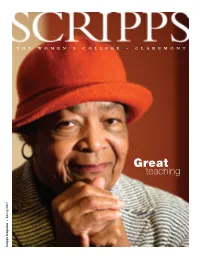

Teaching Spring 2007 • Scripps Magazine 270751 Scripps CVR R1 4/17/07 3:50 PM Page 2

270751_Scripps_CVR_r2 4/19/07 7:27 PM Page 1 THE WOMEN’S COLLEGE • CLAREMONT Great teaching Spring 2007 • Scripps Magazine 270751_Scripps_CVR_r1 4/17/07 3:50 PM Page 2 editor’sPAGE A Room of Our Own I WAS AN ONLY CHILD—FOR A YEAR. That was when my about me.Would she once more be the “good” sister, the one who slightly older sister, Catherine, went off to college while I finished made me feel tongue-tied and inadequate by comparison? Even my last year of high school.We had shared quarters for the past though I now consider her a confidante and love her dearly, was 17 years in our hometown of Glendale, California. In my suddenly I ready to be in competition with her again? single room, I didn’t miss her; in fact, I relished afternoons lying Close to half a century of growing up makes a difference in on one of the room’s twin beds yakking with friends on the phone how one reacts to people and experiences.What once seemed so without unsolicited comments from an all-knowing sibling. I claimed important—my own room, my own bathtub, my own ego—was less half of her abandoned closet for my Pendleton skirts and Peter important than a chance to be with my sister for an extended time Pan-collared blouses and took lengthy baths uninterrupted by away from work and family demands, to have fun and learn together. pounding demands to “get out now!” Bliss. We were two of about 45 travelers who stayed at a hilltop villa in the Chianti region of Tuscany. -

Theseus and the Slaying of the Minotaur

Theseus and the Slaying of the Minotaur The ancient Greeks developed myths about their gods, goddesses, and heroes to help explain the beginnings and early history of their country. Among the most famous of these myths is the story of how Theseus, the greatest hero of Athens, killed the bull-headed man, or Minotaur, that King Minos of Crete kept in a vast labyrinth. The excerpt below is a modern retelling of the story of Theseus and the Minotaur. As you read the excerpt, note the role that the gods played in the story: In requital [repayment] for the murder of Androgeus, [his son] Minos had given orders that the Athenians should send seven youths and seven maidens every ninth year to the Cretan Labyrinth, where the Minotaur waited to devour them. This Minotaur, whose name was Asterius, was the bullheaded monster that [the wife of Minos] had borne to the white bull. Soon after Theseus’s arrival at Athens the tribute fell due for the third time, and he so deeply pitied those parents whose children were liable [eligible] to be chosen by lot, that he offered himself as one of the victims, despite [his father] Aegeu’s earnest attempts at dissuasion [to persuade him otherwise]. On the two previous occasions, the ship which conveyed the fourteen victims had carried black sails, but Theseus was confident that the gods were on his side, and Aegeus therefore gave him a white sail to hoist on return, in signal of success… Theseus sailed on the sixth day of… [April]… When the ship reached Crete some days afterwards,… Minos’s own daughter Ariadne fell in love with [Theseus] at first sight. -

Pausanias' Description of Greece

BONN'S CLASSICAL LIBRARY. PAUSANIAS' DESCRIPTION OF GREECE. PAUSANIAS' TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH \VITTI NOTES AXD IXDEX BY ARTHUR RICHARD SHILLETO, M.A., Soiiii'tinie Scholar of Trinity L'olltge, Cambridge. VOLUME IT. " ni <le Fnusnnias cst un homme (jui ne mnnquo ni de bon sens inoins a st-s tlioux." hnniie t'oi. inais i}iii rn>it ou au voudrait croire ( 'HAMTAiiNT. : ftEOROE BELL AND SONS. YOUK STIIKKT. COVKNT (iAKDKX. 188t). CHISWICK PRESS \ C. WHITTINGHAM AND CO., TOOKS COURT, CHANCEKV LANE. fA LC >. iV \Q V.2- CONTEXTS. PAGE Book VII. ACHAIA 1 VIII. ARCADIA .61 IX. BtEOTIA 151 -'19 X. PHOCIS . ERRATA. " " " Volume I. Page 8, line 37, for Atte read Attes." As vii. 17. 2<i. (Catullus' Aft is.) ' " Page 150, line '22, for Auxesias" read Anxesia." A.-> ii. 32. " " Page 165, lines 12, 17, 24, for Philhammon read " Philanimon.'' " " '' Page 191, line 4, for Tamagra read Tanagra." " " Pa ire 215, linu 35, for Ye now enter" read Enter ye now." ' " li I'aijf -J27, line 5, for the Little Iliad read The Little Iliad.'- " " " Page ^S9, line 18, for the Babylonians read Babylon.'' " 7 ' Volume II. Page 61, last line, for earth' read Earth." " Page 1)5, line 9, tor "Can-lira'" read Camirus." ' ; " " v 1'age 1 69, line 1 , for and read for. line 2, for "other kinds of flutes "read "other thites.'' ;< " " Page 201, line 9. for Lacenian read Laeonian." " " " line 10, for Chilon read Cliilo." As iii. 1H. Pago 264, " " ' Page 2G8, Note, for I iad read Iliad." PAUSANIAS. BOOK VII. ACIIAIA.