Przegląd Kulturoznawczy, 2018, Numer 4 (38)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

Saturday's Graded Stakes Fields P10-11 GOFFS ORBY YEARLING

Saturday’s graded stakes fields p10-11 THURSDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2014 732-747-8060 $ TDN Home Page Click Here STARS SHINES AT ORBY FINALE TAPESTRY TO BE SUPPLEMENTED TO ARC By Emma Berry On a day that a number of G1 Prix de l=Arc de Yet another seven-figure yearling--a i1.1-million Triomphe contenders put in their final works for (US$1,388,004) daughter of Sea the Stars (Ire)--graced France=s i5-million showpiece, the outlook of the race the ring during the final session of the Goffs Orby Sale, was altered yesterday when it was revealed that which ended yesterday with an 11% gain in aggregate Magnier, Tabor, Smith and to i38,450,500, and a clearance rate of 87%. While Flaxman Stables= sophomore the sale=s overall top price of i1.5 million didn=t come filly Tapestry (Ire) (Galileo close to last year=s i2.85-million modern-day Irish {Ire}) would be record for subsequent supplemented to the 2400- Group 2 winner Ol= Man meter contest today, with River (Ire) (Montjeu {Ire}), Ryan Moore to take the repeated six-figure mount. Supplementing will transactions across both cost i120,000, but days ensured a solid rise in Tapestry could be well both average and median, worth it, as she handed of 8% and 23%, current Arc favorite respectively, to 109,234 Taghrooda (GB) (Sea the Session-topping Sea the Stars filly i Sarah Farnsworth and i70,000. Tapestry Stars {Ire}) her lone defeat Hailing the sale as Racing Post in the G1 Yorkshire Oaks AIreland=s best,@ Goffs= Chief Executive Henry Beeby Aug. -

Fantasy Illustration As an Expression of Postmodern 'Primitivism': the Green Man and the Forest Emily Tolson

Fantasy Illustration as an Expression of Postmodern 'Primitivism': The Green Man and the Forest Emily Tolson , Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: Lize Van Robbroeck Co-Supervisor: Paddy Bouma April 2006 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Dedaratfton:n I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any Date o~/o?,}01> 11 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Albs tract This study demonstrates that Fantasy in general, and the Green Man in particular, is a postmodern manifestation of a long tradition of modernity critique. The first chapter focuses on outlining the history of 'primitivist' thought in the West, while Chapter Two discusses the implications of Fantasy as postmodern 'primitivism', with a brief discussion of examples. Chapter Three provides an in-depth look at the Green Man as an example of Fantasy as postmodern 'primitivism'. The fmal chapter further explores the invented tradition of the Green Man within the context of New Age spirituality and religion. The study aims to demonstrate that, like the Romantic counterculture that preceded it, Fantasy is a revolt against increased secularisation, industrialisation and nihilism. The discussion argues that in postmodernism the Wilderness (in the form of the forest) is embraced through the iconography of the Green Man. The Green Man is a pre-Christian symbol found carved in wood and stone, in temples and churches and on graves throughout Europe, but his origins and original meaning are unknown, and remain a controversial topic. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G. Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol) at the University of Edinburgh

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Desire for Perpetuation: Fairy Writing and Re-creation of National Identity in the Narratives of Walter Scott, John Black, James Hogg and Andrew Lang Yuki Yoshino A Thesis Submitted to The University of Edinburgh for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Literature 2013 Abstract This thesis argues that ‘fairy writing’ in the nineteenth-century Scottish literature serves as a peculiar site which accommodates various, often ambiguous and subversive, responses to the processes of constructing new national identities occurring in, and outwith, post-union Scotland. It contends that a pathetic sense of loss, emptiness and absence, together with strong preoccupations with the land, and a desire to perpetuate the nation which has become state-less, commonly underpin the wide variety of fairy writings by Walter Scott, John Black, James Hogg and Andrew Lang. -

2 Tales of the Gnomes 4 3 3

Clarinet in Eb Tales of the Gnomes for clarinet quartet / choir WernerDeBleser 1. Blue Cap q=56 2 # #4 œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ & # 4 œ œ œ œ œ œ œ™ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ mp J f 8 4 # # œ œ œ œ œ & # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ f 14 rit. œ™ œ # # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ & # J ∑ dim. p 2. Korrigan q=120 # #3 . œ . & # 4 œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ Œ f . 5 # # . œ . 3 # œ œ. œ. œ œ œ œ œ. œ. œ œ œ Œ & . œ. œ ˙ 12 3 # # . œ . & # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ Œ f . 19 # # . œ . # œ œ. œ. œ œ œ œ œ. œ. œ œ œ Œ & . œ. nœ ˙ 3. Green Man =52 q 4 ##4 & 4 ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ pœ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ p 9 4 ## œ & œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ w p œ ˙ 2 Tales of the Gnomes - Clarinet in Eb 4. Trow q=120 2 6 #2 œ œ œ & 4 œ Œ œ œ œ œ œ f mf p. 13 # . 8 & œ œ œ œ œ œ œ. œ œ œ œ œ. œ œ mf . œ œ . p 27 # œ- œ œ - œ - - & œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ f - - 33 # - œ œ œ œ œ & œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ 40 # 8 œ & œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ ˙ ™ œ ˙ p f J 55 # j j œ œ œ œ œ œ œ & œ™ œ ˙ œ™ œ œ œ œ œ œ Œ ˙ ™ J f 5. -

Test Your Faerie Knowledge

Spiderwick Tes t Your Activity Sheet Faerie Knowledge It wasn’t all that long ago that faeries were regarded as the substance of the imagination. Boggarts, Elves, Dragons, Ogres . mankind scoffed at the idea that such fantastical beings could exist at all, much less inhabit the world around us. Of course, that was before Simon & Schuster published Arthur Spiderwick’s Field Guide to the Fantastical World Around You. Now, we all know that faeries truly do exist. They’re out there, occasionally helping an unwary human, but more often causing mischief and playing tricks. How much do you know about the Invisible World? Have you studied up on your faerie facts? Put your faerie knowledge to the test and see how well you do in the following activities.When you’re finished, total up your score and see how much you really know. SCORING: 1-10 POINTS: Keep studying. In the meantime, you should probably steer clear of faeries of any kind. 11-20 POINTS: Pretty good! You might be able to trick a pixie, but you couldn’t fool a phooka. 21-30 POINTS: Wow, You’re almost ready to tangle with a troll! 31-39 POINTS: Impressive! You seem to know a lot about the faerie world —perhaps you’re a changeling... 40 POINTS: Arthur Spiderwick? Is that you? MY SCORE: REPRODUCIBLE SHEET Page 1 of 4 ILLUSTRATIONS © 2003, 2004, 2005 BY TONY DITERLIZZI Spiderwick Tes t Your Activity Sheet Faerie Knowledge part 1 At any moment, you could stumble across a fantastical creature of the faerie world. -

Part Two 1914 -1938 Part Two 1914 - 1938

Part Two 1914 -1938 Part Two 1914 - 1938 Childhood and Families Alan Brind My granddad was Herbert Allen (Jack) Laxton 1884 – 1936. He married Eva Whitear from Titchfield in 1913 and they lived at 81 West St. Titchfield. Jack served for 24 years in the 108th Heavy Battery Royal Garrison Artillery which, as Sergeant, he left in 1926. He was a horseman par excellence and served the whole of WW1 in France and Belgium coming through numerous engagements uninjured. He was awarded a Mons Star with Clasp and Roses, British Army War Medal and Victory Medals. He left the army in 1926 and became a bricklayer and worked on the building of Titchfield Primary School and also the Embassy and Savoy cinemas in Fareham. It was ironic that despite having worked with horses throughout his army career, he died, aged 52, following an infection due to a bite from a horse fly. Donald Upshall As I was the first grandchild in the Upshall family I was named after my uncle who was killed in WW1. If you look in the church you will see his name on the remembrance plaque. My father started the garage on East Street when I was born. Now, in 2015, we've been in business 89 years. Today you don't realise how narrow the roads were then. There were no kerbs. You just walked along the edge of the road. But there wasn’t much traffic then. It is so different now of course. I remember the main A27 road. I used to push my brother in his pushchair all the way in to Fareham where they had all these Hornby toys. -

OPELIKA Pride In

ALABAMA POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE. VOL. IX. AVBVRN, ALABAMA, WEDNESDAY. JANVARY 28.1903. NO. 6. Pianoforte Lecture-Recita.1. as a lecture or a concert the en- A SILVER ANNIVERSARY Booming the Annual. The Way to Get is to Give. On Saturday, Jan. 24, Mr. Ed- tertainment would be a success At a meeting of the Glomerata and the combination is truly a Mr. R. W. Burton Celebrates 25th "This is a mighty busy world. ward Baxter Perry, the distin- Bu;ird last Wednesday night it happy idea of Mr. Perry's which Birthday of His Bookstore. We all have to be fed and clothed, guished blkid pianist, gave a was indeed gratifying as well as Probably the moat unique af- and to have warm beds and books recital in Langdon Hall to a was originated by him. encouraging to note the great en- fair in the history of our town and all that. All these things large and appreciative audience. From every point of view the thusiasm manifested in making was the celebration by Mr. R. W. come by labor of some one." said No attraction that has been to recital was a finished perform- preparations and arranging per- Burton, on Friday last, of the Joseph E. Wing to a class of Auburn for some time has been ance—artistic, enjoyable and manent plans for the publication twenty-fifth anniversary of the Ohio school boys. "It happens more enjoyed than was this beneficial—and everyone" who of the Glomerata of "'03." At establishment of his bookstore that this is not a misfortune, .concert, ,.._. -

Uncle Bernac a Memory of the Empire Chapter I The

UNCLE BERNAC A MEMORY OF THE EMPIRE CHAPTER I THE COAST OF FRANCE I dare say that I had already read my uncle's letter a hundred times, and I am sure that I knew it by heart. None the less I took it out of my pocket, and, sitting on the side of the lugger, I went over it again with as much attention as if it were for the first time. It was written in a prim, angular hand, such as one might expect from a man who had begun life as a village attorney, and it was addressed to Louis de Laval, to the care of William Hargreaves, of the Green Man in Ashford, Kent. The landlord had many a hogshead of untaxed French brandy from the Normandy coast, and the letter had found its way by the same hands. 'My dear nephew Louis,' said the letter, 'now that your father is dead, and that you are alone in the world, I am sure that you will not wish to carry on the feud which has existed between the two halves of the family. At the time of the troubles your father was drawn towards the side of the King, and I towards that of the people, and it ended, as you know, by his having to fly from the country, and by my becoming the possessor of the estates of Grosbois. No doubt it is very hard that you should find yourself in a different position to your ancestors, but I am sure that you would rather that the land should be held by a Bernac than by a stranger. -

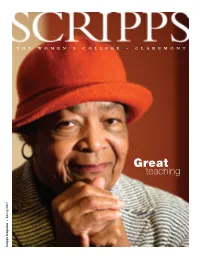

Teaching Spring 2007 • Scripps Magazine 270751 Scripps CVR R1 4/17/07 3:50 PM Page 2

270751_Scripps_CVR_r2 4/19/07 7:27 PM Page 1 THE WOMEN’S COLLEGE • CLAREMONT Great teaching Spring 2007 • Scripps Magazine 270751_Scripps_CVR_r1 4/17/07 3:50 PM Page 2 editor’sPAGE A Room of Our Own I WAS AN ONLY CHILD—FOR A YEAR. That was when my about me.Would she once more be the “good” sister, the one who slightly older sister, Catherine, went off to college while I finished made me feel tongue-tied and inadequate by comparison? Even my last year of high school.We had shared quarters for the past though I now consider her a confidante and love her dearly, was 17 years in our hometown of Glendale, California. In my suddenly I ready to be in competition with her again? single room, I didn’t miss her; in fact, I relished afternoons lying Close to half a century of growing up makes a difference in on one of the room’s twin beds yakking with friends on the phone how one reacts to people and experiences.What once seemed so without unsolicited comments from an all-knowing sibling. I claimed important—my own room, my own bathtub, my own ego—was less half of her abandoned closet for my Pendleton skirts and Peter important than a chance to be with my sister for an extended time Pan-collared blouses and took lengthy baths uninterrupted by away from work and family demands, to have fun and learn together. pounding demands to “get out now!” Bliss. We were two of about 45 travelers who stayed at a hilltop villa in the Chianti region of Tuscany. -

Freshly Caught Fairy Folk Captured by the Fairy Catcher Catching Fairies Since 1991

Freshly Caught Fairy Folk Captured by The Fairy Catcher catching fairies since 1991 The Fairy Catcher specialises in the capture of fairy folk. Using an ointment made from a four leafed Clover to protect you from their magic powers, but please never let them escape from their jars as we cannot be responsible for the consequences. Good Luck! These pages describe the fairies that we catch. The fairies are all held captive in glass jars, and the following descriptions appear on their individual labels. Please visit www.thefairycatcher.com to see them. Good luck! Pisky Ferrishyn Piskies are from Cornwall and The Ferrishyn are the trooping fairies of although they are fond of The Isle of Man. They love hunting and playing practical jokes have very good hearing, on people who have lost they can hear whatever their way in the countryside is said out of doors. they can bring luck and Every wind stirring good fortune carries the sound to their ears. Take care to speak well of them, then Knocker luck and good fortune Knockers come from Cornwall and used to help the Tin Miners could be yours. by knocking to indicate where a rich batch of ore Buggane could be found. Listen The Buggane is a goblin from The Isle of Man. He lives in a for their knocking, Dub into which the Spooty falls. He will change his shape if there could be he is set free, and it isnot unusual for a Buggane to turn into a rich vein in store a very large water horse! for you! Browney The Browney is a cornish guardian of the bees. -

The Continent of Faerie Was Colonised Once Before, by a Nameless Race Of

The continent of Faerie was colonised once before, by a nameless race of men who sailed west across the trackless Atlantic in the time before the Romans came to Britain. Their dykes and dolmens still scar the land. Their degenerate descendants, the Hairy Men, fell to worshipping pagan gods and became little better than beasts. By the time of St. Brendan the Navigator, who first claimed the continent for Christendom, they were too deeply steeped in sin to greet him with anything but sticks and stones. The Marcher Lords followed in Brendan’s wake. They hold their corner of Faerie in the name of England’s king, though not a man among them is certain of his name. They keep the peace, suppress the Hairy Men, mount pointless campaigns against each other and sponsor doomed military expeditions into the western wilderness. Their peasants labour as thanklessly as they would in any other feudal state. A steady stream of exiles, rogues and outcasts arrive in the eastern harbours, fleeing persecution or seeking fortune. Time flows differently here. A man may return to England after years of adventure to find that only a night has passed, and the warrant for his arrest is just as active as it was the day he left. PCs are more likely to be bandits or militiamen than knights. All clerics are Christian, but may have different powers depending on the saint they are devoted to. Magicians tend to have fey blood. Each Lord only controls about a single six-mile hex - the Marches are largely unpoliced, and taking a message to another Lord is an adventure in itself.