Fantasy Illustration As an Expression of Postmodern 'Primitivism': the Green Man and the Forest Emily Tolson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

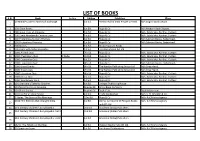

List of Books S.N

LIST OF BOOKS S.N. Book Author Edition Publisher Place 10 Minute Guide to Microsoft Exchange. 1st Ed. Prentic-Hall of India Private Limited. M/s English Book Depot 1 2 100 Great Books. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Modern Book Depote, 3 100 Great Lives of Antiquity. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 4 100 Great Nineteenth Century Lives. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 5 100 Pretentious Nursery Rhymes. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 6 100 Pretentious Proverbs. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 7 100 Stories. 1st Ed. Better Yourself Books 8 100 Years with Nobel Laureates. 1st Ed. I K International Pvt Ltd 9 1000 Animal Quiz. 7th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 10 1000 Chemistery Quiz. C Dube 3rd Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 11 1000 Economics Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 12 1000 Economics Quiz. 4th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 13 1000 Great Events. 6th Ed. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. M/s Dreamland, 14 1000 Great Lives. 7th Ed. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. M/s Dreamland, 15 1000 Literature Quiz. 4th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 16 1000 Orissa Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 17 1000 Wordpower Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 18 101 Grandma's Tales for Children. 1st Ed. Dhingra Publishing House 19 101 Moral Stories of Grandpa. -

Readercon 14

readercon 14 program guide The conference on imaginative literature, fourteenth edition readercon 14 The Boston Marriott Burlington Burlington, Massachusetts 12th-14th July 2002 Guests of Honor: Octavia E. Butler Gwyneth Jones Memorial GoH: John Brunner program guide Practical Information......................................................................................... 1 Readercon 14 Committee................................................................................... 2 Hotel Map.......................................................................................................... 4 Bookshop Dealers...............................................................................................5 Readercon 14 Guests..........................................................................................6 Readercon 14: The Program.............................................................................. 7 Friday..................................................................................................... 8 Saturday................................................................................................14 Sunday................................................................................................. 21 Readercon 15 Advertisement.......................................................................... 26 About the Program Participants......................................................................27 Program Grids...........................................Back Cover and Inside Back Cover Cover -

2 Tales of the Gnomes 4 3 3

Clarinet in Eb Tales of the Gnomes for clarinet quartet / choir WernerDeBleser 1. Blue Cap q=56 2 # #4 œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ & # 4 œ œ œ œ œ œ œ™ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ mp J f 8 4 # # œ œ œ œ œ & # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ f 14 rit. œ™ œ # # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ & # J ∑ dim. p 2. Korrigan q=120 # #3 . œ . & # 4 œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ Œ f . 5 # # . œ . 3 # œ œ. œ. œ œ œ œ œ. œ. œ œ œ Œ & . œ. œ ˙ 12 3 # # . œ . & # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ Œ f . 19 # # . œ . # œ œ. œ. œ œ œ œ œ. œ. œ œ œ Œ & . œ. nœ ˙ 3. Green Man =52 q 4 ##4 & 4 ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ pœ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ p 9 4 ## œ & œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ w p œ ˙ 2 Tales of the Gnomes - Clarinet in Eb 4. Trow q=120 2 6 #2 œ œ œ & 4 œ Œ œ œ œ œ œ f mf p. 13 # . 8 & œ œ œ œ œ œ œ. œ œ œ œ œ. œ œ mf . œ œ . p 27 # œ- œ œ - œ - - & œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ f - - 33 # - œ œ œ œ œ & œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ 40 # 8 œ & œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ ˙ ™ œ ˙ p f J 55 # j j œ œ œ œ œ œ œ & œ™ œ ˙ œ™ œ œ œ œ œ œ Œ ˙ ™ J f 5. -

2020 Summer Publishing Institute (SPI)

NOW OPEN TO RISING COLLEGE SENIORS! June 1–July 10 SUMMER 2020 PUBLISHING INSTITUTE (SPI) BOOKS AND DIGITAL/MAGAZINE MEDIA Center for Publishing: Digital and Print Media OVERVIEW NYU SPI students meeting with Grace Bastidas (third from left), Editor of Parents Latina, at a reception at the Meredith Corporation. Our best advocates are our alumni, as their comments on these pages show. At the 2020 NYU Summer Publishing “SPI taught me more than I Institute, we look forward to welcoming a new class of ever could have imagined, but aspiring publishing leaders and helping them to achieve their I’m most thankful for the dreams. Located in New York City, the media capital of the community the program world, SPI also is at the center of the constantly evolving helped me to create. Between publishing landscape. Media is changing—and so are we. fellow students, alumni, and With a focus on book, digital, and magazine media, we professional contacts, I left SPI emphasize the learning of new skills and strategies to equip with an army of support that our students to tackle the challenges facing publishing and to helped me narrow my focus prepare them for careers in the industry. Workshops and and ultimately break into the sessions on career preparation with leading HR recruiters book publishing industry.” provide students what they need to succeed in the workforce. Courtney Smith, Digital By combining the study of publishing fundamentals with Marketing Associate, Simon & sessions on vital industry trends and digital strategies, SPI Schuster and SPI 2019 graduate provides firsthand, inside knowledge of what’s happening right now and what’s on the horizon in the publishing industry. -

Orbital Debris: a Chronology

NASA/TP-1999-208856 January 1999 Orbital Debris: A Chronology David S. F. Portree Houston, Texas Joseph P. Loftus, Jr Lwldon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas David S. F. Portree is a freelance writer working in Houston_ Texas Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................ iv Preface ........................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................... vii Acronyms and Abbreviations ........................................................................................ ix The Chronology ............................................................................................................. 1 1961 ......................................................................................................................... 4 1962 ......................................................................................................................... 5 963 ......................................................................................................................... 5 964 ......................................................................................................................... 6 965 ......................................................................................................................... 6 966 ........................................................................................................................ -

Reference Document Including the Annual Financial Report

REFERENCE DOCUMENT INCLUDING THE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT 2012 PROFILE LAGARDÈRE, A WORLD-CLASS PURE-PLAY MEDIA GROUP LED BY ARNAUD LAGARDÈRE, OPERATES IN AROUND 30 COUNTRIES AND IS STRUCTURED AROUND FOUR DISTINCT, COMPLEMENTARY DIVISIONS: • Lagardère Publishing: Book and e-Publishing; • Lagardère Active: Press, Audiovisual (Radio, Television, Audiovisual Production), Digital and Advertising Sales Brokerage; • Lagardère Services: Travel Retail and Distribution; • Lagardère Unlimited: Sport Industry and Entertainment. EXE LOGO L'Identité / Le Logo Les cotes indiquées sont données à titre indicatif et devront être vérifiées par les entrepreneurs. Ceux-ci devront soumettre leurs dessins Echelle: d’éxécution pour approbation avant réalisation. L’étude technique des travaux concernant les éléments porteurs concourant la stabilité ou la solidité du bâtiment et tous autres éléments qui leur sont intégrés ou forment corps avec eux, devra être vérifié par un bureau d’étude qualifié. Agence d'architecture intérieure LAGARDERE - Concept C5 - O’CLOCK Optimisation Les entrepreneurs devront s’engager à executer les travaux selon les règles de l’art et dans le respect des règlementations en vigueur. Ce 15, rue Colbert 78000 Versailles Date : 13 01 2010 dessin est la propriété de : VERSIONS - 15, rue Colbert - 78000 Versailles. Ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation. tél : 01 30 97 03 03 fax : 01 30 97 03 00 e.mail : [email protected] PANTONE 382C PANTONE PANTONE 382C PANTONE Informer, Rassurer, Partager PROCESS BLACK C PROCESS BLACK C Les cotes indiquées sont données à titre indicatif et devront être vérifiées par les entrepreneurs. Ceux-ci devront soumettre leurs dessins d’éxécution pour approbation avant réalisation. L’étude technique des travaux concernant les éléments porteurs concourant la stabilité ou la Echelle: Agence d'architecture intérieure solidité du bâtiment et tous autres éléments qui leur sont intégrés ou forment corps avec eux, devra être vérifié par un bureau d’étude qualifié. -

2014 Midwinter Highlights

2014 Midwinter Highlights Cognotes ALAPHILADELPHIA, PA February 2014 ALA Announces 2014 Youth Media Awards in Philadelphia The American Library Coretta Scott King Book Association (ALA) announced Award, recognizing an Afri- the top books, video, and can-American author and il- audio books for children and lustrator of outstanding books young adults – including the for children and young adults: Caldecott, Coretta Scott King, P.S. Be Eleven by Rita Newbery and Printz awards – Williams-Garcia is the King at its Midwinter Meeting in Author Book winner. Three Philadelphia. King Author Honor Books John Newbery Medal for were selected: March: Book the most outstanding contri- One by John Lewis and An- bution to children’s literature: drew Aydin, illustrated by Flora & Ulysses: The Nate Powell; Darius & Twig Illuminated Adventures by by Walter Dean Myers; and Kate DiCamillo is the 2014 Words with Wings by Nikki Newbery Medal winner. Four Grimes. Newbery Honor Books also Knock Knock: My Dad’s were named: Doll Bones by Dream for Me, illustrated Holly Black; The Year of Billy by Bryan Collier, is the King Miller by Kevin Henkes; One Illustrator Book winner. The Came Home by Amy Timber- » see page 10 lake; and Paperboy by Vince Book committee members and librarians react as the Youth Media Awards are announced at the Vawter. Pennsylvania Convention Center January 27 during the 2014 Midwinter Meeting & Exhibits. Randolph Caldecott Medal for the most distin- by Brian Floca, is the 2014 cott Honor Books also were ten and illustrated by Molly guished American picture Caldecott Medal winner. The named: Journey, written and Idle; and Mr. -

OPELIKA Pride In

ALABAMA POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE. VOL. IX. AVBVRN, ALABAMA, WEDNESDAY. JANVARY 28.1903. NO. 6. Pianoforte Lecture-Recita.1. as a lecture or a concert the en- A SILVER ANNIVERSARY Booming the Annual. The Way to Get is to Give. On Saturday, Jan. 24, Mr. Ed- tertainment would be a success At a meeting of the Glomerata and the combination is truly a Mr. R. W. Burton Celebrates 25th "This is a mighty busy world. ward Baxter Perry, the distin- Bu;ird last Wednesday night it happy idea of Mr. Perry's which Birthday of His Bookstore. We all have to be fed and clothed, guished blkid pianist, gave a was indeed gratifying as well as Probably the moat unique af- and to have warm beds and books recital in Langdon Hall to a was originated by him. encouraging to note the great en- fair in the history of our town and all that. All these things large and appreciative audience. From every point of view the thusiasm manifested in making was the celebration by Mr. R. W. come by labor of some one." said No attraction that has been to recital was a finished perform- preparations and arranging per- Burton, on Friday last, of the Joseph E. Wing to a class of Auburn for some time has been ance—artistic, enjoyable and manent plans for the publication twenty-fifth anniversary of the Ohio school boys. "It happens more enjoyed than was this beneficial—and everyone" who of the Glomerata of "'03." At establishment of his bookstore that this is not a misfortune, .concert, ,.._. -

Mythic Journeys Corporate Sponsors and Partners

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 27, 2004 MEDIA CONTACTS: Anya Martin (678) 468-3867 Dawn Zarimba Edelman Public Relations (404) 262-3000 [email protected] Mythic Journeys Corporate Sponsors and Partners Corporate Sponsors The Krispy Kreme Foundation (http://www.krispykreme.com/) The Krispy Kreme Foundation was created to help people, individually and collectively, achieve their potential and enrich their lives. The foundation is guided by the belief that stories have the unique ability to reveal and illuminate the ways in which individuals, organizations, nations and cultures are part of an integrated and interdependent whole. The Krispy Kreme Foundation promotes stories and storytelling, which both support individual and collective efforts to choose a future that is resonate with the best in the human spirit. Borders’ Books & Music (http://www.bordersgroupinc.com ) With approximately 450 locations in the United States, Borders Books & Music stores can be found in all parts of the country. Borders Group also operates 36 Books etc. locations in the United Kingdom as well as 37 Borders superstores throughout the U.K., Australia, New Zealand, Singapore and the commonwealth of Puerto Rico. More than 32,000 Borders Books & Music employees worldwide help to provide our customers with the books, music, movies, and other entertainment items tailored specifically to the interests of the community they serve. We are a company committed to our people, to diversity, to our customers, and to our communities. PARABOLA Magazine (http://www.parabola.org/) PARABOLA is a quarterly journal and one of the pioneering publications on the subject of myth and tradition. Every issue explores one of the facets of human existence from the point of view of as many of the world's religious and spiritual traditions as possible, through the prism of story and symbol, myth, ritual and sacred teachings. -

Uncle Bernac a Memory of the Empire Chapter I The

UNCLE BERNAC A MEMORY OF THE EMPIRE CHAPTER I THE COAST OF FRANCE I dare say that I had already read my uncle's letter a hundred times, and I am sure that I knew it by heart. None the less I took it out of my pocket, and, sitting on the side of the lugger, I went over it again with as much attention as if it were for the first time. It was written in a prim, angular hand, such as one might expect from a man who had begun life as a village attorney, and it was addressed to Louis de Laval, to the care of William Hargreaves, of the Green Man in Ashford, Kent. The landlord had many a hogshead of untaxed French brandy from the Normandy coast, and the letter had found its way by the same hands. 'My dear nephew Louis,' said the letter, 'now that your father is dead, and that you are alone in the world, I am sure that you will not wish to carry on the feud which has existed between the two halves of the family. At the time of the troubles your father was drawn towards the side of the King, and I towards that of the people, and it ended, as you know, by his having to fly from the country, and by my becoming the possessor of the estates of Grosbois. No doubt it is very hard that you should find yourself in a different position to your ancestors, but I am sure that you would rather that the land should be held by a Bernac than by a stranger. -

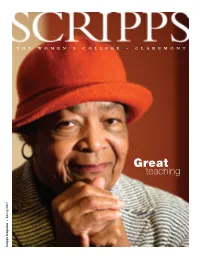

Teaching Spring 2007 • Scripps Magazine 270751 Scripps CVR R1 4/17/07 3:50 PM Page 2

270751_Scripps_CVR_r2 4/19/07 7:27 PM Page 1 THE WOMEN’S COLLEGE • CLAREMONT Great teaching Spring 2007 • Scripps Magazine 270751_Scripps_CVR_r1 4/17/07 3:50 PM Page 2 editor’sPAGE A Room of Our Own I WAS AN ONLY CHILD—FOR A YEAR. That was when my about me.Would she once more be the “good” sister, the one who slightly older sister, Catherine, went off to college while I finished made me feel tongue-tied and inadequate by comparison? Even my last year of high school.We had shared quarters for the past though I now consider her a confidante and love her dearly, was 17 years in our hometown of Glendale, California. In my suddenly I ready to be in competition with her again? single room, I didn’t miss her; in fact, I relished afternoons lying Close to half a century of growing up makes a difference in on one of the room’s twin beds yakking with friends on the phone how one reacts to people and experiences.What once seemed so without unsolicited comments from an all-knowing sibling. I claimed important—my own room, my own bathtub, my own ego—was less half of her abandoned closet for my Pendleton skirts and Peter important than a chance to be with my sister for an extended time Pan-collared blouses and took lengthy baths uninterrupted by away from work and family demands, to have fun and learn together. pounding demands to “get out now!” Bliss. We were two of about 45 travelers who stayed at a hilltop villa in the Chianti region of Tuscany.