Francisco García Fitz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor RESEARCH IN MEDIEVAL CULTURE Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Medieval Institute Publications is a program of The Medieval Institute, College of Arts and Sciences Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor MEDIEVAL INSTITUTE PUBLICATIONS Western Michigan University Kalamazoo Copyright © 2015 by the Board of Trustees of Western Michigan University All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Taylor, Robert A. (Robert Allen), 1937- Bibliographical guide to the study of the troubadours and old Occitan literature / Robert A. Taylor. pages cm Includes index. Summary: "This volume provides offers an annotated listing of over two thousand recent books and articles that treat all categories of Occitan literature from the earli- est enigmatic texts to the works of Jordi de Sant Jordi, an Occitano-Catalan poet who died young in 1424. The works chosen for inclusion are intended to provide a rational introduction to the many thousands of studies that have appeared over the last thirty-five years. The listings provide descriptive comments about each contri- bution, with occasional remarks on striking or controversial content and numerous cross-references to identify complementary studies or differing opinions" -- Pro- vided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-58044-207-7 (Paperback : alk. paper) 1. Provençal literature--Bibliography. 2. Occitan literature--Bibliography. 3. Troubadours--Bibliography. 4. Civilization, Medieval, in literature--Bibliography. -

Marchese Di Verrucola E Di Margherita Anguissola

Nikolai Wandruszka: Un viaggio nel passato europeo – gli antenati del Marchese Antonio Amorini Bolognini (1767-1845) e sua moglie, la Contessa Marianna Ranuzzi (1771-1848) 14.4.2011 (26.6.2013), 2.9.2018; 10.9.2018 MALASPINA (I, II) incl. SALERNO, BARBIANO di CUNIO VIII.303 Malaspina Flavia, * err. 1564 (ex 1°), Testament vorhanden1; oo kurz vor 1582 Orazio Boldieri (+1594/1609), oo (b) 1609 Alberto Pompei. Er hatte zuerst versucht, Flavias Tochter Auriga zu entführen und nachdem dies nicht gelungen war, entführte er die Mutter2. A novembre del 1609 viene rapita Flavia Malaspina Boldieri, futura suocera di Giovanni Tommaso Canossa. Questi nel marzo del 1609 a sua volta aveva fatto rapire una fanciulla del popolo. Nella tecnica di esecuzione i due rapimenti non ... ; ihre Brüder sind Giovanni Francesco (1561-1577), Lucius Marcius (1562-1577), Filippa (+ als Kleinkind), Flavia (1573 9-jährig) und Paoloverginio (*25.1.1576, + 4-jährig) – letzteres Datum nach PORCACCHI kann so nicht stimmen, da der Vater ja 1573 gestorben ist. Derselbe Autor berichtet, “... che siamo del 1573 … Flavia, c'hora a vive in eta di nove anni, con miserabil creanza et famiglianza alla bella, saggia, honesta et valorosa madre”. Zur Ehe Flavias mit Boldieri berichtet er “ne se le conveniva un altro marito, essendo questi signori [i.e. die Boldieri] per madre usciti da Auriga Malaspina …. tal che due volte sono inserite et con legitimi nodi ligati insieme queste due case ...”3; durch den Tod ihrer Brüder ist sie 1577 testament. Erbin von Giovanni Francesco und wird 14.10.1588 in Person ihres Ehemannes D. -

WORKSHOP: Around the World in 30 Instruments Educator’S Guide [email protected]

WORKSHOP: Around The World In 30 Instruments Educator’s Guide www.4shillingsshort.com [email protected] AROUND THE WORLD IN 30 INSTRUMENTS A MULTI-CULTURAL EDUCATIONAL CONCERT for ALL AGES Four Shillings Short are the husband-wife duo of Aodh Og O’Tuama, from Cork, Ireland and Christy Martin, from San Diego, California. We have been touring in the United States and Ireland since 1997. We are multi-instrumentalists and vocalists who play a variety of musical styles on over 30 instruments from around the World. Around the World in 30 Instruments is a multi-cultural educational concert presenting Traditional music from Ireland, Scotland, England, Medieval & Renaissance Europe, the Americas and India on a variety of musical instruments including hammered & mountain dulcimer, mandolin, mandola, bouzouki, Medieval and Renaissance woodwinds, recorders, tinwhistles, banjo, North Indian Sitar, Medieval Psaltery, the Andean Charango, Irish Bodhran, African Doumbek, Spoons and vocals. Our program lasts 1 to 2 hours and is tailored to fit the audience and specific music educational curriculum where appropriate. We have performed for libraries, schools & museums all around the country and have presented in individual classrooms, full school assemblies, auditoriums and community rooms as well as smaller more intimate settings. During the program we introduce each instrument, talk about its history, introduce musical concepts and follow with a demonstration in the form of a song or an instrumental piece. Our main objective is to create an opportunity to expand people’s understanding of music through direct expe- rience of traditional folk and world music. ABOUT THE MUSICIANS: Aodh Og O’Tuama grew up in a family of poets, musicians and writers. -

A Concise History of the Baptists

A Concise History Of The Baptists FROM THE TIME OF CHRIST THEIR FOUNDER TO THE 18TH CENTURY. Taken from the New Testament, the first fathers, early writers, and historians of all ages; CHRONOLOGICALLY ARRANGED; Exhibiting their churches with their order in various countries under different names from the establishment of Christianity to the present age: with correlative information, supporting the early and only practice of believers’ immersion: also OBSERVATIONS AND NOTES on the abuse of the ordinance, and the rise of minor and infant baptism. By G. H. Orchard Baptist Minister, Steventon, Bedfordshire, England, 1855 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE Section 1: Primitive Baptists Section 2: Primitive Baptists Continued Section 3: Primitive Baptists Continued Section 4: Primitive Baptists Continued CHAPTER TWO Section 1: Churches in Italy Section 2: African Churches Section 3: African Churches Continued Section 4: Oriental Churches Section 5: Oriental Churches Continued Section 6: Churches in Italy Resumed Section 7: Churches in Gaul Section 8: Churches in France Continued Section 9: Churches in France Continued Section 10: Churches in Bohemia Section 11: Churches in Piedmont Section 12: German and Dutch Baptists BAPTIST HISTORY A Concise History Of The Baptists By G. H. Orchard CHAPTER 1 SECTION I: PRIMITIVE BAPTISTS. "From the days of John the Baptist till now, the kingdom of heaven suffereth violence, and the violent taketh it by force."--Matt. 11:12. 1. Ecclesiastical history must ever prove an interesting subject to every true lover of Zion. Not only does every saint feel personally interested in her blessings, but he solicitously wishes and prays for their diffusion, as widely as the miseries of man prevail. -

Fantasy Illustration As an Expression of Postmodern 'Primitivism': the Green Man and the Forest Emily Tolson

Fantasy Illustration as an Expression of Postmodern 'Primitivism': The Green Man and the Forest Emily Tolson , Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: Lize Van Robbroeck Co-Supervisor: Paddy Bouma April 2006 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Dedaratfton:n I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any Date o~/o?,}01> 11 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Albs tract This study demonstrates that Fantasy in general, and the Green Man in particular, is a postmodern manifestation of a long tradition of modernity critique. The first chapter focuses on outlining the history of 'primitivist' thought in the West, while Chapter Two discusses the implications of Fantasy as postmodern 'primitivism', with a brief discussion of examples. Chapter Three provides an in-depth look at the Green Man as an example of Fantasy as postmodern 'primitivism'. The fmal chapter further explores the invented tradition of the Green Man within the context of New Age spirituality and religion. The study aims to demonstrate that, like the Romantic counterculture that preceded it, Fantasy is a revolt against increased secularisation, industrialisation and nihilism. The discussion argues that in postmodernism the Wilderness (in the form of the forest) is embraced through the iconography of the Green Man. The Green Man is a pre-Christian symbol found carved in wood and stone, in temples and churches and on graves throughout Europe, but his origins and original meaning are unknown, and remain a controversial topic. -

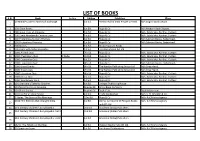

List of Books S.N

LIST OF BOOKS S.N. Book Author Edition Publisher Place 10 Minute Guide to Microsoft Exchange. 1st Ed. Prentic-Hall of India Private Limited. M/s English Book Depot 1 2 100 Great Books. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Modern Book Depote, 3 100 Great Lives of Antiquity. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 4 100 Great Nineteenth Century Lives. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 5 100 Pretentious Nursery Rhymes. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 6 100 Pretentious Proverbs. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 7 100 Stories. 1st Ed. Better Yourself Books 8 100 Years with Nobel Laureates. 1st Ed. I K International Pvt Ltd 9 1000 Animal Quiz. 7th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 10 1000 Chemistery Quiz. C Dube 3rd Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 11 1000 Economics Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 12 1000 Economics Quiz. 4th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 13 1000 Great Events. 6th Ed. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. M/s Dreamland, 14 1000 Great Lives. 7th Ed. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. M/s Dreamland, 15 1000 Literature Quiz. 4th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 16 1000 Orissa Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 17 1000 Wordpower Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 18 101 Grandma's Tales for Children. 1st Ed. Dhingra Publishing House 19 101 Moral Stories of Grandpa. -

Inmate Release Report Snapshot Taken: 9/28/2021 6:00:10 AM

Inmate Release Report Snapshot taken: 9/28/2021 6:00:10 AM Projected Release Date Booking No Last Name First Name 9/29/2021 6090989 ALMEDA JONATHAN 9/29/2021 6249749 CAMACHO VICTOR 9/29/2021 6224278 HARTE GREGORY 9/29/2021 6251673 PILOTIN MANUEL 9/29/2021 6185574 PURYEAR KORY 9/29/2021 6142736 REYES GERARDO 9/30/2021 5880910 ADAMS YOLANDA 9/30/2021 6250719 AREVALO JOSE 9/30/2021 6226836 CALDERON ISAIAH 9/30/2021 6059780 ESTRADA CHRISTOPHER 9/30/2021 6128887 GONZALEZ JUAN 9/30/2021 6086264 OROZCO FRANCISCO 9/30/2021 6243426 TOBIAS BENJAMIN 10/1/2021 6211938 ALAS CHRISTOPHER 10/1/2021 6085586 ALVARADO BRYANT 10/1/2021 6164249 CASTILLO LUIS 10/1/2021 6254189 CASTRO JAYCEE 10/1/2021 6221163 CUBIAS ERICK 10/1/2021 6245513 MYERS ALBERT 10/1/2021 6084670 ORTIZ MATTHEW 10/1/2021 6085145 SANCHEZ ARAFAT 10/1/2021 6241199 SANCHEZ JORGE 10/1/2021 6085431 TORRES MANLIO 10/2/2021 6250453 ALVAREZ JOHNNY 10/2/2021 6241709 ESTRADA JOSE 10/2/2021 6242141 HUFF ADAM 10/2/2021 6254134 MEJIA GERSON 10/2/2021 6242125 ROBLES GUSTAVO 10/2/2021 6250718 RODRIGUEZ RAFAEL 10/2/2021 6225488 SANCHEZ NARCISO 10/2/2021 6248409 SOLIS PAUL 10/2/2021 6218628 VALDEZ EDDIE 10/2/2021 6159119 VERNON JIMMY 10/3/2021 6212939 ADAMS LANCE 10/3/2021 6239546 BELL JACKSON 10/3/2021 6222552 BRIDGES DAVID 10/3/2021 6245307 CERVANTES FRANCISCO 10/3/2021 6252321 FARAMAZOV ARTUR 10/3/2021 6251594 GOLDEN DAMON 10/3/2021 6242465 GOSSETT KAMERA 10/3/2021 6237998 MOLINA ANTONIO 10/3/2021 6028640 MORALES CHRISTOPHER 10/3/2021 6088136 ROBINSON MARK 10/3/2021 6033818 ROJO CHRISTOPHER 10/3/2021 -

The Trecento Lute

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title The Trecento Lute Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1kh2f9kn Author Minamino, Hiroyuki Publication Date 2019 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Trecento Lute1 Hiroyuki Minamino ABSTRACT From the initial stage of its cultivation in Italy in the late thirteenth century, the lute was regarded as a noble instrument among various types of the trecento musical instruments, favored by both the upper-class amateurs and professional court giullari, participated in the ensemble of other bas instruments such as the fiddle or gittern, accompanied the singers, and provided music for the dancers. Indeed, its delicate sound was more suitable in the inner chambers of courts and the quiet gardens of bourgeois villas than in the uproarious battle fields and the busy streets of towns. KEYWORDS Lute, Trecento, Italy, Bas instrument, Giullari any studies on the origin of the lute begin with ancient Mesopota- mian, Egyptian, Greek, or Roman musical instruments that carry a fingerboard (either long or short) over which various numbers M 2 of strings stretch. The Arabic ud, first widely introduced into Europe by the Moors during their conquest of Spain in the eighth century, has been suggest- ed to be the direct ancestor of the lute. If this is the case, not much is known about when, where, and how the European lute evolved from the ud. The presence of Arabs in the Iberian Peninsula and their cultivation of musical instruments during the middle ages suggest that a variety of instruments were made by Arab craftsmen in Spain. -

2020 Summer Publishing Institute (SPI)

NOW OPEN TO RISING COLLEGE SENIORS! June 1–July 10 SUMMER 2020 PUBLISHING INSTITUTE (SPI) BOOKS AND DIGITAL/MAGAZINE MEDIA Center for Publishing: Digital and Print Media OVERVIEW NYU SPI students meeting with Grace Bastidas (third from left), Editor of Parents Latina, at a reception at the Meredith Corporation. Our best advocates are our alumni, as their comments on these pages show. At the 2020 NYU Summer Publishing “SPI taught me more than I Institute, we look forward to welcoming a new class of ever could have imagined, but aspiring publishing leaders and helping them to achieve their I’m most thankful for the dreams. Located in New York City, the media capital of the community the program world, SPI also is at the center of the constantly evolving helped me to create. Between publishing landscape. Media is changing—and so are we. fellow students, alumni, and With a focus on book, digital, and magazine media, we professional contacts, I left SPI emphasize the learning of new skills and strategies to equip with an army of support that our students to tackle the challenges facing publishing and to helped me narrow my focus prepare them for careers in the industry. Workshops and and ultimately break into the sessions on career preparation with leading HR recruiters book publishing industry.” provide students what they need to succeed in the workforce. Courtney Smith, Digital By combining the study of publishing fundamentals with Marketing Associate, Simon & sessions on vital industry trends and digital strategies, SPI Schuster and SPI 2019 graduate provides firsthand, inside knowledge of what’s happening right now and what’s on the horizon in the publishing industry. -

'In the Footsteps of the Ancients'

‘IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE ANCIENTS’: THE ORIGINS OF HUMANISM FROM LOVATO TO BRUNI Ronald G. Witt BRILL ‘IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE ANCIENTS’ STUDIES IN MEDIEVAL AND REFORMATION THOUGHT EDITED BY HEIKO A. OBERMAN, Tucson, Arizona IN COOPERATION WITH THOMAS A. BRADY, Jr., Berkeley, California ANDREW C. GOW, Edmonton, Alberta SUSAN C. KARANT-NUNN, Tucson, Arizona JÜRGEN MIETHKE, Heidelberg M. E. H. NICOLETTE MOUT, Leiden ANDREW PETTEGREE, St. Andrews MANFRED SCHULZE, Wuppertal VOLUME LXXIV RONALD G. WITT ‘IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE ANCIENTS’ ‘IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE ANCIENTS’ THE ORIGINS OF HUMANISM FROM LOVATO TO BRUNI BY RONALD G. WITT BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON • KÖLN 2001 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Witt, Ronald G. ‘In the footsteps of the ancients’ : the origins of humanism from Lovato to Bruni / by Ronald G. Witt. p. cm. — (Studies in medieval and Reformation thought, ISSN 0585-6914 ; v. 74) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 9004113975 (alk. paper) 1. Lovati, Lovato de, d. 1309. 2. Bruni, Leonardo, 1369-1444. 3. Latin literature, Medieval and modern—Italy—History and criticism. 4. Latin literature, Medieval and modern—France—History and criticism. 5. Latin literature, Medieval and modern—Classical influences. 6. Rhetoric, Ancient— Study and teaching—History—To 1500. 7. Humanism in literature. 8. Humanists—France. 9. Humanists—Italy. 10. Italy—Intellectual life 1268-1559. 11. France—Intellectual life—To 1500. PA8045.I6 W58 2000 808’.0945’09023—dc21 00–023546 CIP Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Witt, Ronald G.: ‘In the footsteps of the ancients’ : the origins of humanism from Lovato to Bruni / by Ronald G. -

Orbital Debris: a Chronology

NASA/TP-1999-208856 January 1999 Orbital Debris: A Chronology David S. F. Portree Houston, Texas Joseph P. Loftus, Jr Lwldon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas David S. F. Portree is a freelance writer working in Houston_ Texas Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................ iv Preface ........................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................... vii Acronyms and Abbreviations ........................................................................................ ix The Chronology ............................................................................................................. 1 1961 ......................................................................................................................... 4 1962 ......................................................................................................................... 5 963 ......................................................................................................................... 5 964 ......................................................................................................................... 6 965 ......................................................................................................................... 6 966 ........................................................................................................................ -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal .