Conclusion Space Politics and Policy: Facing the Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issues Paper on Exploring Space Technologies for Sustainable Development and the Benefits of International Research Collaboration in This Context

United Nations Commission on Science and Technology for Development Inter-sessional Panel 2019-2020 7-8 November 2019 Geneva, Switzerland Issues Paper on Exploring space technologies for sustainable development and the benefits of international research collaboration in this context Draft Not to be cited Prepared by UNCTAD Secretariat1 18 October 2019 1 Contributions from the Governments of Austria, Belgium, Botswana, Brazil, Canada, Japan, Mexico, South Africa, Turkey, the United Kingdom, United States of America, as well as from the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, the Food and Agriculture Organization, the International Telecommunication Union, the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction and the World Food Programme are gratefully acknowledged. Contents Table of figures ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Table of boxes ......................................................................................................................................... 3 I. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 4 II. Space technologies for the Sustainable Development Goals ......................................................... 5 1. Food security and agriculture ..................................................................................................... 5 2. Health applications .................................................................................................................... -

Fantasy Illustration As an Expression of Postmodern 'Primitivism': the Green Man and the Forest Emily Tolson

Fantasy Illustration as an Expression of Postmodern 'Primitivism': The Green Man and the Forest Emily Tolson , Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: Lize Van Robbroeck Co-Supervisor: Paddy Bouma April 2006 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Dedaratfton:n I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any Date o~/o?,}01> 11 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Albs tract This study demonstrates that Fantasy in general, and the Green Man in particular, is a postmodern manifestation of a long tradition of modernity critique. The first chapter focuses on outlining the history of 'primitivist' thought in the West, while Chapter Two discusses the implications of Fantasy as postmodern 'primitivism', with a brief discussion of examples. Chapter Three provides an in-depth look at the Green Man as an example of Fantasy as postmodern 'primitivism'. The fmal chapter further explores the invented tradition of the Green Man within the context of New Age spirituality and religion. The study aims to demonstrate that, like the Romantic counterculture that preceded it, Fantasy is a revolt against increased secularisation, industrialisation and nihilism. The discussion argues that in postmodernism the Wilderness (in the form of the forest) is embraced through the iconography of the Green Man. The Green Man is a pre-Christian symbol found carved in wood and stone, in temples and churches and on graves throughout Europe, but his origins and original meaning are unknown, and remain a controversial topic. -

Honorarable Chair, Distinguished Delegates, It Is an Honour for Me to Address the Scientific and Technical Subcommittee of COPUO

February 2020 United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space 57th Session of COPUOS STSC Austria, Vienna, 3 - 14 February 2020 Statement of the International Astronautical Federation (IAF) Honorarable Chair, Distinguished Delegates, It is an honour for me to address the Scientific and Technical Subcommittee of COPUOS in my capacity as IAF Vice- President for Relations with International Organizations and representing the newly elected IAF President, Prof. Pascale Ehrenfreund, who could not join us today. Distinguished Delegates, Since its creation in 1951 the IAF has pursued its main goal to provide a platform for organizations, communities and individuals, active and enthusiastic about space, to meet, share knowledge and connect with each other in a cooperative spirit. Following its mission of Connecting @ll Space People, the IAF continuously seeks to deepen international cooperation worldwide by encouraging the advancement of knowledge about space and fostering dialogue between scientists, engineers, policy makers and all other space actors for the benefit of humanity. Please allow me to briefly highlight some of the IAF’s manifold past activities and also give you an outlook on some upcoming events: IAF Secretariat - 100 Avenue de Suffren - 75015 Paris, France T: +33 (0)1 45 67 42 60 - E: [email protected] - W: www.iafastro.org Non-profit organisation established under the French Law of 1 July 1901 The 70th International Astronautical Congress held in Washington, D.C., United States was an outstanding success with more than 6.800 participants coming from over 80 countries, for an intense week of events, meetings, and discoveries. The Congress started with the Honorable Mike Pence, Vice President of the United States, confirming the USA plans to go forward to the Moon and land the first woman and the next man on the Lunar surface by 2024. -

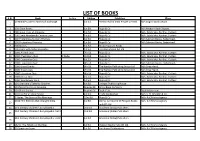

List of Books S.N

LIST OF BOOKS S.N. Book Author Edition Publisher Place 10 Minute Guide to Microsoft Exchange. 1st Ed. Prentic-Hall of India Private Limited. M/s English Book Depot 1 2 100 Great Books. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Modern Book Depote, 3 100 Great Lives of Antiquity. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 4 100 Great Nineteenth Century Lives. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 5 100 Pretentious Nursery Rhymes. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 6 100 Pretentious Proverbs. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 7 100 Stories. 1st Ed. Better Yourself Books 8 100 Years with Nobel Laureates. 1st Ed. I K International Pvt Ltd 9 1000 Animal Quiz. 7th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 10 1000 Chemistery Quiz. C Dube 3rd Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 11 1000 Economics Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 12 1000 Economics Quiz. 4th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 13 1000 Great Events. 6th Ed. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. M/s Dreamland, 14 1000 Great Lives. 7th Ed. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. M/s Dreamland, 15 1000 Literature Quiz. 4th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 16 1000 Orissa Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 17 1000 Wordpower Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 18 101 Grandma's Tales for Children. 1st Ed. Dhingra Publishing House 19 101 Moral Stories of Grandpa. -

PHILIPPINES’ NATIONAL STATEMENT to the UNISPACE+5O HIGH-LEVEL SEGMENT 20-21 JUNE 2018, VIENNA INTERNATIONAL CENTER

PHILIPPINES’ NATIONAL STATEMENT TO THE UNISPACE+5o HIGH-LEVEL SEGMENT 20-21 JUNE 2018, VIENNA INTERNATIONAL CENTER TO BE DELIVERED BY ATTY. EMMANUEL S. GALVEZ ASSISTANT SECRETARY FOR FINANCE AND LEGAL AFFAIRS, DEPARTMENT OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Ms. Simonetta Di Pippo, UNOOSA Director, Ms. Rosa Maria del Refugio Ramirez de Arellano v Haro, COPUOS Chairperson, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen, Good afternoon. On behalf of the Philippine Government, allow me to extend my warmest felicitations and congratulations to UNOOSA Director Ms. Di Pippo, COPUOS Chairperson Ms. Arellano the fiftieth y(5oth)Haro and all Signatory States for the successful milestone commemoration of anniversary of the first United Nations Conference on the Exploration and Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UNISPACE+5o). The UNISPACE+5o process endeavors to build a foundation that would help define the role of space activities in addressing the overarching long-term development concerns and contributing to global efforts towards achieving the goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The Philippines strongly supports the Space 2030 Agenda as it endeavors to create a vision for space cooperation by strengthening the mandate of the COPUOS as unique platform for international cooperation in the peaceful uses of outer space. As we take note of the contributions of the three conferences to global space governance, 50 years of space exploration and international cooperation on the peaceful uses of outer space, the Philippines is humbled as it has vet to harness fully the potential of the peaceful uses of outer space and reap the benefits of space innovation. There is a pending legislation with the House of Representatives on the proposed Philippines Space Development and Utilization Policy, and the Creation of the Philippines Space Agency. -

Afghanistan Anam Ahmed | Elizabethtown High School

Afghanistan Anam Ahmed | Elizabethtown High School Head of State: Ashraf Ghani GDP: 664.76 USD per capita Population: 33,895,000 UN Ambassador: Mahmoud Saikal Joined UN: 1946 Current Member of UNSC: No Past UNSC Membership: No Issue 1: Immigration, Refugees, and Asylum Seekers Afghanistan is the highest refugee producing country with roughly six million refugees. Regarding immigration and refugees, Afghanistan believes that all neighboring countries to those with the highest refugee count, such as Syria and Afghanistan, need to have an open door policy to these individuals. The refugees would need to be approved by the government in order to enter and live in the country; however, if denied access they must not be forced back. Refugee camps with adequate food, water, medical help, and shelter must be provided by the UN and its members in order to reduce refugee suffering. Although many of the countries around the world will disagree with this plan, they fail to realize the severity of this issue. In Afghanistan millions of individuals are left to fend for themselves in a foreign land with literally nothing but the clothes on their back. As a country with over six million refugees, we are able understand the necessity for a change in the current situation. The UN distinguishes between asylum seekers and refugees, however those who are not accepted by others need not be excluded from having a proper life. With the dramatic increase of refugees and immigrants around the world resulting from the dramatic increase of wars of crises, the UN must acknowledge and call all people fleeing from their country refugees and not distinguish between the two. -

Kennedy's Quest: Leadership in Space

Kennedy’s Quest: Leadership in Space Overview Topic: “Space Race” Grade Level: 9-12 Subject Area: US History Time Required: One class period. Goals/Rationale: The decision by the Kennedy Administration to make a manned lunar landing the major goal of the US space program derived from political as well as scientific motivations. In this lesson plan, students do a close reading of four primary sources related to the US space program in 1961, analyzing how and why public statements made by the White House regarding space may have differed from private statements made within the Kennedy Administration. Essential Questions: How was the “Space Race” connected to the Cold War? How and why might the White House communicate differently in public and in private? How might the Administration garner support for their policy? Objectives Students will be able to: analyze primary sources, considering the purpose of the source, the audience, and the occasion. analyze the differences in the tone or content of the primary sources. explain the Kennedy Administration’s arguments for putting a human on the Moon by the end of the 1960s. Connections to Curriculum (Standards) National History Standards US History, Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s) Standard 2A: The student understands the international origins and domestic consequences of the Cold War. Historical Thinking Skills Standard 2: Historical Comprehension Reconstruct the literal meaning of a historical passage. Appreciate historical perspectives . Historical Thinking Skills Standard 4: Historical Research Capabilities Support interpretations with historical evidence. Massachusetts History and Social Science Curriculum Frameworks USII [T.5] 1. Using primary sources such as campaign literature and debates, news articles/analyses, editorials, and television coverage, analyze the important policies and events that took place during the presidencies of John F. -

Space Diplomacy & Making “Space for Women” Leaders

Space Diplomacy & Making “Space for Women” Leaders UNITED NATIONS EXPERT MEETING ON ‘SPACE FOR WOMEN” 4th – 6th October 2017 New York, USA Namira Salim Founder & Executive Chairperson Space Trust Space Diplomacy & Making “Space for Women” Leaders A New Space Age Commercialization or Democratization of Space Opens the Final Frontier to All Sectors 10% 37% 14% 2016 $329 Billion Global Space Economy Total Annual Revenue 39% Non US Govt Space Budgets US Govt Space Budgets Comm. Space P + S Comm. Infrastructure & Industry Space Report 2016 - Space Foundation Encouraging Public- Triggering a New Complex Space Private Partnerships Space Economy Environment From the Edge of Space to Low Earth Orbit, to the Moon, Mars & Beyond Space Diplomacy & Making “Space for Women” Leaders SPACE DIPLOMACY & MAKING “SPACE FOR WOMEN” LEADERS Our NewSpace Age or “Democratisation of Space” provides low-cost access to space and makes space "Inclusive for All." Spacefaring & New Space Nations expanding cooperation in Low Earth Orbit, to asteroids, the Moon, Mars & beyond via human & robotic missions Deep Space Habitats & colonies on Mars will Evolve Humans into Inter- Planetary Ambassadors As the final frontier opens to all sectors, why not open space to world leaders and above all, women in global leadership roles to find innovative solutions for a peaceful world? Raise awareness for Space Diplomacy on the institutional level Advocate & encourage Women Leaders in Political Sectors & Female Heads of State to exercise space diplomacy in an increasingly complex -

2020 Summer Publishing Institute (SPI)

NOW OPEN TO RISING COLLEGE SENIORS! June 1–July 10 SUMMER 2020 PUBLISHING INSTITUTE (SPI) BOOKS AND DIGITAL/MAGAZINE MEDIA Center for Publishing: Digital and Print Media OVERVIEW NYU SPI students meeting with Grace Bastidas (third from left), Editor of Parents Latina, at a reception at the Meredith Corporation. Our best advocates are our alumni, as their comments on these pages show. At the 2020 NYU Summer Publishing “SPI taught me more than I Institute, we look forward to welcoming a new class of ever could have imagined, but aspiring publishing leaders and helping them to achieve their I’m most thankful for the dreams. Located in New York City, the media capital of the community the program world, SPI also is at the center of the constantly evolving helped me to create. Between publishing landscape. Media is changing—and so are we. fellow students, alumni, and With a focus on book, digital, and magazine media, we professional contacts, I left SPI emphasize the learning of new skills and strategies to equip with an army of support that our students to tackle the challenges facing publishing and to helped me narrow my focus prepare them for careers in the industry. Workshops and and ultimately break into the sessions on career preparation with leading HR recruiters book publishing industry.” provide students what they need to succeed in the workforce. Courtney Smith, Digital By combining the study of publishing fundamentals with Marketing Associate, Simon & sessions on vital industry trends and digital strategies, SPI Schuster and SPI 2019 graduate provides firsthand, inside knowledge of what’s happening right now and what’s on the horizon in the publishing industry. -

NASA's Strategic Direction and the Need for a National Consensus

NASA's Strategic Direction and the Need for a National Consensus NASAs Strategic Direction and the Need for a National Consensus Committee on NASAs Strategic Direction Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS Washington, D.C. www.nap.edu PREPUBLICATION COPYSUBJECT TO FURTHER EDITORIAL CORRECTION Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. NASA's Strategic Direction and the Need for a National Consensus THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS 500 Fifth Street, NW Washington, DC 20001 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. This study is based on work supported by Contract NNH10CC48B between the National Academy of Sciences and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the agency that provided support for the project. International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-309-XXXXX-X International Standard Book Number-10: 0-309-XXXXX-X Copies of this report are available free of charge from: Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences National Research Council 500 Fifth Street, NW Washington, DC 20001 Additional copies of this report are available from the National Academies Press, 500 Fifth Street, NW, Keck 360, Washington, DC 20001; (800) 624-6242 or (202) 334-3313; http://www.nap.edu. -

Corporate Profile

2013 : Epsilon Launch Vehicle 2009 : International Space Station 1997 : M-V Launch Vehicle 1955 : The First Launched Pencil Rocket Corporate Profile Looking Ahead to Future Progress IHI Aerospace (IA) is carrying out the development, manufacture, and sales of rocket projectiles, and has been contributing in a big way to the indigenous space development in Japan. We started research on rocket projectiles in 1953. Now we have become a leading comprehensive manufacturer carrying out development and manufacture of rocket projectiles in Japan, and are active in a large number of fields such as rockets for scientific observation, rockets for launching practical satellites, and defense-related systems, etc. In the space science field, we cooperate with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) to develop and manufacture various types of observational rockets named K (Kappa), L (Lambda), and S (Sounding), and the M (Mu) rockets. With the M rockets, we have contributed to the launch of many scientific satellites. In 2013, efforts resulted in the successful launch of an Epsilon Rocket prototype, a next-generation solid rocket which inherited the 2 technologies of all the aforementioned rockets. In the practical satellite booster rocket field, We cooperates with the JAXA and has responsibilities in the solid propellant field including rocket boosters, upper-stage motors in development of the N, H-I, H-II, and H-IIA H-IIB rockets. We have also achieved excellent results in development of rockets for material experiments and recovery systems, as well as the development of equipment for use in a space environment or experimentation. In the defense field, we have developed and manufactured a variety of rocket systems and rocket motors for guided missiles, playing an important role in Japanese defense. -

Orbital Debris: a Chronology

NASA/TP-1999-208856 January 1999 Orbital Debris: A Chronology David S. F. Portree Houston, Texas Joseph P. Loftus, Jr Lwldon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas David S. F. Portree is a freelance writer working in Houston_ Texas Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................ iv Preface ........................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................... vii Acronyms and Abbreviations ........................................................................................ ix The Chronology ............................................................................................................. 1 1961 ......................................................................................................................... 4 1962 ......................................................................................................................... 5 963 ......................................................................................................................... 5 964 ......................................................................................................................... 6 965 ......................................................................................................................... 6 966 ........................................................................................................................