Morgan Le Fay As Other in English Medieval and Modern Texts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Echoes of Legend: Magic As the Bridge Between a Pagan Past And

Winthrop University Digital Commons @ Winthrop University Graduate Theses The Graduate School 5-2018 Echoes of Legend: Magic as the Bridge Between a Pagan Past and a Christian Future in Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte Darthur Josh Mangle Winthrop University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Mangle, Josh, "Echoes of Legend: Magic as the Bridge Between a Pagan Past and a Christian Future in Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte Darthur" (2018). Graduate Theses. 84. https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses/84 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ECHOES OF LEGEND: MAGIC AS THE BRIDGE BETWEEN A PAGAN PAST AND A CHRISTIAN FUTURE IN SIR THOMAS MALORY’S LE MORTE DARTHUR A Thesis Presented to the Faculty Of the College of Arts and Sciences In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Of Master of Arts In English Winthrop University May 2018 By Josh Mangle ii Abstract Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur is a text that tells the story of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. Malory wrote this tale by synthesizing various Arthurian sources, the most important of which being the Post-Vulgate cycle. Malory’s work features a division between the Christian realm of Camelot and the pagan forces trying to destroy it. -

Camelot the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival Camelot The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. The Study Guide is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2011, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print The Study Guide, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Anne Newhall (left) as Billie Dawn and Craig Spidle as Harry Brock in Born Yesterday, 2003. Contents InformationCamelot on the Play Synopsis 4 Characters 5 About the Playwright 6 Scholarly Articles on the Play A Pygmalion Tale, but So Much More 8 Well in Advance of Its Time 10 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 8FTU$FOUFS4USFFUr $FEBS$JUZ 6UBIr Synopsis: Camelot On a frosty morning centuries ago in the magical kingdom of Camelot, King Arthur prepares to greet his promised bride, Guenevere. Merlyn the magician, the king’s lifelong mentor, finds Arthur, a reluctant king and even a more reluctant suitor, hiding in a tree. -

Lancelot - the Truth Behind the Legend by Rupert Matthews

Lancelot - The Truth behind the Legend by Rupert Matthews Published by Bretwalda Books at Smashwords Website : Facebook : Twitter This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author. First Published 2013 Copyright © Rupert Matthews 2013 Rupert Matthews asserts his moral rights to be regarded as the author of this book. ISBN 978-1-909698-64-2 CONTENTS Introduction Chapter 1 - Lancelot the Legend Chapter 2 - Lancelot in France Chapter 3 - Lancelot in Britain Conclusion Introduction Of all the Knights of the Round Table, none is so famous as Sir Lancelot. He is both the finest of the Arthurian knights, and the worst. He is the champion of the Round Table, and the reason for its destruction. He is loyal, yet treacherous. Noble, but base. His is a complex character that combines the best and worst of the world of chivalry in one person. It is Sir Lancelot who features in every modern adaptation of the old stories. Be it an historical novel, a Hollywood movie or a British TV series, Lancelot is centre stage. He is usually shown as a romantically flawed hero doomed to eventual disgrace by the same talents and skills that earn him fame in the first place. -

Elemental Motes by Charles Choi Illustration by Rob Alexamder Little Fires up the Imagination More Than a Vision of the Well

Fantastic Terrain: Elemental Motes By Charles Choi illustration by Rob Alexamder Little fires up the imagination more than a vision of the well. The awe-inspiring heights that motes often soar at carry impossible, such as an island defying gravity by floating miles the promise of death-defying acts of derring-do that can stick high up in the air. This might be why castles in the sky are so with players for years. Although the constant risk of a poten- common in fantasy, from the ethereal cloud kingdoms seen tially lethal fall underlies the greatest strength of motes as a in fairy tales such as Jack and the Beanstalk to the ominous storytelling tool—spine-tingling suspense—unfortunately, it is flying citadels of Krynn in Dragonlance. also their greatest weakness. One wrong step on the part of either Dungeon Master or player, and a player character or Islands in the sky made their debut in 4th Edition as valuable nonplayer character can inadvertently go hurtling earthmotes in the updated Forgotten Realms® setting, and into the brink. However, such challenges can be overcome now they can be unforgettable elements in your campaign as easily with a little forethought. TM & © 2009 Wizards of the Coast LLC All rights reserved. March 2010 | Dungeon 176 76 Fantastic Terrain: Elemental Motes Motes in On the flipside, in settings where air travel is common, such as the Eberron® setting, motes Facts abouT Motes Your CaMpaign could become common ports of call. Such mote- Motes are often born from breaches between the ports can brim with adventure and serve as home mortal world and the Elemental Chaos, when matter In a game that includes monster-infested dungeons, to all kinds of intrigue. -

Camelot: Rules

Original Game Design: Tom Jolly Additional Game Design: Aldo Ghiozzi C a m e l o t : V a r i a t i o n R u l e s Playing Piece Art & Box Cover Art: The Fraim Brothers Game Board Art: Thomas Denmark Graphic Design & Box Bottom Art: Alvin Helms Playtesters: Rick Cunningham, Dan Andoetoe, Mike Murphy, A C C O U T R E M E N T S O F K I N G S H I P T H E G U A R D I A N S O F T H E S W O R D Dave Johnson, Pat Stapleton, Kristen Davis, Ray Lee, Nick Endsley, Nate Endsley, Mathew Tippets, Geoff Grigsby, Instead of playing to capture Excalibur, you can play In this version, put aside one of the 6 sets of tokens (or © 2005 by Tom Jolly Allan Sugarbaker, Matt Stipicevich, Mark Pentek and Aldo Ghiozzi to capture the Accoutrements of Kingship (hereafter make 2 new tokens for this purpose). Take two of the referred to as "Items") from the rest of the castle, Knights (Lancelots) from that set and place them efore there was King Arthur, there was… well, same time. Each player controls a small army of 15 returning the collected loot to your Entry. If you can within 2 spaces of Excalibur before the game starts. Arthur was a pretty common name back then, pieces, attempting to grab Excalibur from the claim any 2 of the 4 Items (the Crown, the Scepter, During the game, any player may move and attack with B since every mother wanted their little Arthur to center of the game board and return it to their the Robe, the Throne) one or both of these Knights, or use one of these be king, and frankly nobody really knew who "the real starting location. -

Actions Héroïques

Shadows over Camelot FAQ 1.0 Oct 12, 2005 The following FAQ lists some of the most frequently asked questions surrounding the Shadows over Camelot boardgame. This list will be revised and expanded by the Authors as required. Many of the points below are simply a repetition of some easily overlooked rules, while a few others offer clarifications or provide a definitive interpretation of rules. For your convenience, they have been regrouped and classified by general subject. I. The Heroic Actions A Knight may only do multiple actions during his turn if each of these actions is of a DIFFERENT nature. For memory, the 5 possible action types are: A. Moving to a new place B. Performing a Quest-specific action C. Playing a Special White card D. Healing yourself E. Accusing another Knight of being the Traitor. Example: It is Sir Tristan's turn, and he is on the Black Knight Quest. He plays the last Fight card required to end the Quest (action of type B). He thus automatically returns to Camelot at no cost. This move does not count as an action, since it was automatically triggered by the completion of the Quest. Once in Camelot, Tristan will neither be able to draw White cards nor fight the Siege Engines, if he chooses to perform a second Heroic Action. This is because this would be a second Quest-specific (Action of type B) action! On the other hand, he could immediately move to another new Quest (because he hasn't chosen a Move action (Action of type A.) yet. -

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight As a Loathly Lady Tale by Lauren Chochinov a Thesis Submitted to the Facult

Distressing Damsels: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight as a Loathly Lady Tale By Lauren Chochinov A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of English University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba Copyright © 2010 by Lauren Chochinov Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-70110-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-70110-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Land of Faerie: the Disappearing Myth

Volume 5 Number 2 Article 1 10-15-1978 Land of Faerie: The Disappearing Myth Caroline Geer Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Geer, Caroline (1978) "Land of Faerie: The Disappearing Myth," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 5 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol5/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Discusses various theories for the origins of fairies (and tales about them) in myth, history, and religion. Additional Keywords Faerie—Origins; Fairy tales—Origins; Fairy tales—Relation to Myth; Bonnie GoodKnight This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol5/iss2/1 LAND OF FAERIE: THE DISAPPEARING MYTH by Caroline Geer So an age ended, and its last deliverer died Tolkien, however, asserts that "history often resembles In bed, grown idle and unhappy; they were safe: 'myth,' because they are both ultim ately of the same stuff. -

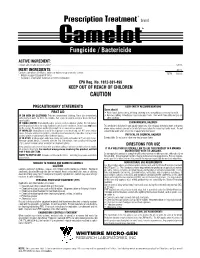

Camelot* Fungicide / Bactericide

® Prescription Treatment brand Camelot* Fungicide / Bactericide ACTIVE INGREDIENT: Copper salts of fatty and rosin acids† . 58.0% INERT INGREDIENTS: . 42.0% Contains petroleum distillates, xylene or xylene range aromatic solvent. TOTAL 100.0% † Metallic Copper Equivalent 5.14%) * Camelot is a registered Trademark of Griffin Corporation. EPA Reg. No. 1812-381-499 KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN CAUTION PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS USER SAFETY RECOMMENDATIONS Users should: FIRST AID • Wash hands before eating, drinking, chewing gum, using tobacco or using the toilet. IF ON SKIN OR CLOTHING: Take off contaminated clothing. Rinse skin immediately • Remove clothing immediately if pesticide gets inside. Then wash thoroughly and put on with plenty of water for 15 to 20 minutes. Call a poison control center or doctor for treat- clean clothing. ment advice. IF SWALLOWED: Immediately call a poison control center or doctor. Do not induce ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS vomiting unless told to do so by a poison control center or doctor. Do not give any liquid This pesticide is toxic to fish and aquatic organisms. Do not apply directly to water, or to areas to the person. Do not give anything by mouth to an unconscious person. where surface water is present or to intertidal areas below the mean high water mark. Do not IF INHALED: Move person to fresh air. If person is not breathing, call 911 or an ambu- contaminate water when disposing of equipment washwaters. lance, then give artificial respiration, preferably mouth-to-mouth, if possible. Call a poison control center or doctor for further treatment advice. PHYSICAL OR CHEMICAL HAZARDS IF IN EYES: Hold eye open and rinse slowly and gently with water for 15 to 20 minutes. -

Meike Weijtmans S4235797 BA Thesis English Language and Culture Supervisor: Dr

Weijtmans, s4235797/1 Meike Weijtmans s4235797 BA Thesis English Language and Culture Supervisor: dr. Chris Cusack Examiner: dr. L.S. Chardonnens August 15, 2018 The Celtic Image in Contemporary Adaptations of the Arthurian Legend M.A.S. Weijtmans BA Thesis August 15, 2018 Weijtmans, s4235797/2 ENGELSE TAAL EN CULTUUR Teacher who will receive this document: dr. Chris Cusack, dr. L.S. Chardonnens Title of document: The Celtic Image in Contemporary Adaptations of the Arthurian Legend Name of course: BA Thesis Date of submission: August 15, 2018 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed Name of student: Meike Weijtmans Student number: s4235797 Weijtmans, s4235797/3 Abstract Celtic culture has always been a source of interest in contemporary popular culture, as it has been in the past; Greek and Roman writers painted the Celts as barbaric and uncivilised peoples, but were impressed with their religion and mythology. The Celtic revival period gave birth to the paradox that still defines the Celtic image to this day, namely that the rurality, simplicity and spirituality of the Celts was to be admired, but that they were uncivilised, irrational and wild at the same time. Recent debates surround the concepts of “Celt”, “Celticity” and “Celtic” are also discussed in this thesis. The first part of this thesis focuses on Celtic history and culture, as well as the complexities surrounding the terminology and the construction of the Celtic image over the centuries. This main body of the thesis analyses the way Celtic elements in contemporary adaptations of the Arthurian narrative form the modern Celtic image. -

Feasting in Homeric Epic 303

HESPERIA 73 (2004) FEASTING IN Pages 301-337 HOMERIC EPIC ABSTRACT Feasting plays a centralrole in the Homeric epics.The elements of Homeric feasting-values, practices, vocabulary,and equipment-offer interesting comparisonsto the archaeologicalrecord. These comparisonsallow us to de- tect the possible contribution of different chronologicalperiods to what ap- pearsto be a cumulative,composite picture of around700 B.c.Homeric drink- ing practicesare of particularinterest in relation to the history of drinkingin the Aegean. By analyzing social and ideological attitudes to drinking in the epics in light of the archaeologicalrecord, we gain insight into both the pre- history of the epics and the prehistoryof drinkingitself. THE HOMERIC FEAST There is an impressive amount of what may generally be understood as feasting in the Homeric epics.' Feasting appears as arguably the single most frequent activity in the Odysseyand, apart from fighting, also in the Iliad. It is clearly not only an activity of Homeric heroes, but also one that helps demonstrate that they are indeed heroes. Thus, it seems, they are shown doing it at every opportunity,to the extent that much sense of real- ism is sometimes lost-just as a small child will invariablypicture a king wearing a crown, no matter how unsuitable the circumstances. In Iliad 9, for instance, Odysseus participates in two full-scale feasts in quick suc- cession in the course of a single night: first in Agamemnon's shelter (II. 1. thanks to John Bennet, My 9.89-92), and almost immediately afterward in the shelter of Achilles Peter Haarer,and Andrew Sherrattfor Later in the same on their return from their coming to my rescueon variouspoints (9.199-222). -

Elemental Magic: All-New Tales of the Elemental Masters Free Ebook

FREEELEMENTAL MAGIC: ALL-NEW TALES OF THE ELEMENTAL MASTERS EBOOK Mercedes Lackey | 320 pages | 04 Dec 2012 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780756407872 | English | New York, United States Elementary: All-New Tales of the Elemental Masters This collection of short stories is a combination of new tales in Mercedes Lackey's Elemental Masters world, with a weird injection of some authors who have no idea what the Elements should be like. "Fire-Water" by Samuel Conway brings a fishhawk to a rabbit to stop a small war. Among Mercedes Lackey’s many novels, few are as critically acclaimed and beloved as those about the Elemental Masters. The novels in this series are loosely based on classic fairy tales, and take place in a fantasy version of turn-of-the-century London, where magic is real and Elemental Masters control the powers of Fire, Water, Air, and Earth. Among Mercedes Lackey's many novels, few are as critically acclaimed and beloved as those about the Elemental Masters. The novels in this series are loosely based on classic fairy tales, and take place in a fantasy version of turn- of-the-century London, where magic is real and Elemental Masters control the powers of Fire, Water, Air, and Earth. Elemental Masters Series Among Mercedes Lackey’s many novels, few are as critically acclaimed and beloved as those about the Elemental Masters. The novels in this series are loosely based on classic fairy tales, and take place in a fantasy version of turn-of-the-century London, where magic is real and Elemental Masters control the powers of Fire, Water, Air, and Earth.