King Leopold's Bonds and the Odious Debts Mystery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Thesis

MASTERARBEIT ANALYSING THE POTENTIAL OF NETWORK KERNEL DENSITY ESTIMATION FOR THE STUDY OF TOURISM BASED ON GEOSOCIAL MEDIA DATA Ausgeführt am Department für Geodäsie und Geoinformation der Technischen Universität Wien unter der Anleitung von Francisco Porras Bernárdez, M.Sc., TU Wien und Prof. Dr. Nico Van de Weghe, Universität Gent (Belgien) Univ.Prof. Mag.rer.nat. Dr.rer.nat. Georg Gartner, TU Wien durch Marko Tošić Laaer-Berg-Straße 47B/1028B, 1100 Wien 10.09.2019 Unterschrift (Student) MASTER’S THESIS ANALYSING THE POTENTIAL OF NETWORK KERNEL DENSITY ESTIMATION FOR THE STUDY OF TOURISM BASED ON GEOSOCIAL MEDIA DATA Conducted at the Department of Geodesy and Geoinformation Vienna University of Technology Under the supervision of Francisco Porras Bernárdez, M.Sc., TU Wien and Prof. Dr. Nico Van de Weghe, Ghent University (Belgium) Univ.Prof. Mag.rer.nat. Dr.rer.nat. Georg Gartner, TU Wien by Marko Tošić Laaer-Berg-Straße 47B/1028B, 1100 Vienna 10.09.2019 Signature (Student) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS If someone told me two years ago that I will sit now in a computer room of the Cartography Research Group at TU Wien, writing Acknowledgments of my finished master’s thesis, I would say “I don’t believe you!” This whole experience is something that I will always carry with me. Different cities, universities, people, cultures, learning and becoming proficient in a completely new field; these two years were a rollercoaster. First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Francisco Porras Bernárdez, muchas gracias por tu paciencia, motivación y apoyo, por compartir tu conocimiento conmigo. Esta tesis fue posibile gracias a ti. -

My Own Affairs

[YOWN AFFAIRS By THE PRINCESS LOUISE OF BELGIUM ^.^ MY OWN AFFAIRS ':y:-.:':l.A MY OWN AFFAIRS By The Princess Louise ofBelgium With Photogravure Frontispiece and Eight Plates Translated by Maude M, C. ffoulkes CASSELL AND COMPANY, LIMITED London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne 1921 I DEDICATE THIS [BOOK TO the Great Man, to the Great King, who was MY FATHER 4S6573 CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE 1. Why I Write this Book i 2. My Beloved Belgium; my Family and Myself; Myself—as I Know Myself .... 7 3. The Queen 17 4. The King 27 5. My Country and Days of my Youth ... 36 6. My Marriage and the Austrian Court—the Day after my marriage 54 7. Married 63 8. My Hosts AT THE Hofburg—the Emperor Francis Joseph and the Empress Elizabeth . 82 9. My Sister Stephanie Marries the Archduke Rudolph, who Died at Meyerung . 100 10. Ferdinand of Coburg and the Court of Sofia . 116 11. William II and the Court of Berlin—the Emperor of Illusion 133 12. The Holsteins 142 13. The Courts of Munich and Old Germany . 154 14. Queen Victoria 165 Contents CHAPTIK PAQB 15. The Drama of my Captivity, and my Life as a Prisoner—THE Commencement of Torture . 171 16. LiNDENHOF 189 17. How I Regained my Liberty and at the Same Time was Declared Sane . -197 18. The Death of the King—Intrigues and Legal Proceedings 211 19. My Sufferings during the War . 231 20. In the Hope of Rest 245 Index 253 vm LIST OF PLATES The Princess Louise of Belgium (Photogravure) Frontispiece FACING PAGE Queen Marie Henriette of Belgium ... -

APPENDIX Belgian and Polish Governments and Ministers Responsible for Education (

APPENDIX Belgian and Polish Governments and Ministers Responsible for Education ( Table A.1. Belgian governments and ministers responsible for education Minister Responsible Government Political Profi le Beginning End for Education Gérard Catholic, liberal, 31.05.1918 13.11.1918 Charles de Broqueville Cooreman socialist 21.11.1918 – 20.11.1918 Léon Catholic, liberal, 21.11.1918 17.11.1919 Charles de Broqueville Delacroix socialist 21.11.1918 – 02.12.1919 Léon Catholic, liberal, 02.12.1919 25.10.1920 Jules Renkin Delacroix socialist 02.12.1919 – 02.06.1920 Henri Jaspar 02.06.1920 – 19.11.1920 Henri Carton Catholic, liberal, 20.11.1920 19.10.1921 Henri Carton de Wiart de Wiart socialist 20.11.1920 – 23.10.1921 Henri Carton Catholic, liberal 24.10.1921 20.11.1921 Henri Carton de Wiart de Wiart 24.10.1921 – 20.11.1921 Georges Catholic, liberal 16.12.1921 27.02.1924 Paul Berryer Theunis 16.12.1921 – 10.03.1924 Georges Catholic, liberal 11.03.1924 05.04.1925 Paul Berryer Theunis 11.03.1924 – 05.04.1925 Aloys Van Catholic 13.05.1925 22.05.1925 de Vyvere Prosper Catholic, 17.06.1925 11.05.1926 Camille Huysmans Poullet socialist 17.06.1925 – 11.05.1926 Henri Jaspar Catholic, liberal, 20.05.1926 21.11.1927 Camille Huysmans socialist 20.05.1926 – 22.11.1927 This open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license thanks to the support of Centre for Contemporary and Digital History at the University of Luxembourg. Not for resale. -

The Belgian Federal Parliament

The Belgian Federal Parliament Welcome to the Palace of the Nation PUBLISHED BY The Belgian House of Representatives and Senate EDITED BY The House Department of Public Relations The Senate Department of Protocol, Reception & Communications PICTURES Guy Goossens, Kevin Oeyen, Kurt Van den Bossche and Inge Verhelst, KIK-IRPA LAYOUT AND PRINTING The central printing offi ce of the House of Representatives July 2019 The Federal Parliament The Belgian House of Representatives and Senate PUBLISHED BY The Belgian House of Representatives and Senate EDITED BY The House Department of Public Relations The Senate Department of Protocol, Reception & Communications PICTURES This guide contains a concise description of the workings Guy Goossens, Kevin Oeyen, Kurt Van den Bossche and Inge Verhelst, KIK-IRPA of the House of Representatives and the Senate, LAYOUT AND PRINTING and the rooms that you will be visiting. The central printing offi ce of the House of Representatives The numbers shown in the margins refer to points of interest July 2019 that you will see on the tour. INTRODUCTION The Palace of the Nation is the seat of the federal parliament. It is composed of two chambers: the House of Representatives and the Senate. The House and the Senate differ in terms of their composition and competences. 150 representatives elected by direct universal suffrage sit in the House of Representatives. The Senate has 60 members. 50 senators are appointed by the regional and community parliaments, and 10 senators are co-opted. The House of Representatives and the Senate are above all legislators. They make laws. The House is competent for laws of every kind. -

Arnesen CV GWU Website June 2009

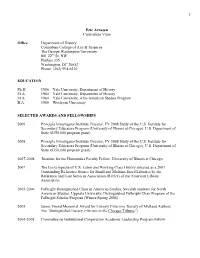

1 Eric Arnesen Curriculum Vitae Office Department of History Columbian College of Arts & Sciences The George Washington University 801 22nd St. NW Phillips 335 Washington, DC 20052 Phone: (202) 994-6230 EDUCATION Ph.D. 1986 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Afro-American Studies Program B.A. 1980 Wesleyan University SELECTED AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS 2009 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2008 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2007-2008 Institute for the Humanities Faculty Fellow, University of Illinois at Chicago 2007 The Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working Class History selected as a 2007 Outstanding Reference Source for Small and Medium-Sized Libraries by the Reference and User Services Association (RUSA) of the American Library Association. 2005-2006 Fulbright Distinguished Chair in American Studies, Swedish Institute for North American Studies, Uppsala University, Distinguished Fulbright Chair Program of the Fulbright Scholar Program (Winter-Spring 2006) 2005 James Friend Memorial Award for Literary Criticism, Society of Midland Authors (for “distinguished literary criticism in the Chicago Tribune”) 2004-2005 Committee on Institutional -

La Turquie Et L'europe

La Turquie et L’Europe - Un Exemple: Alessandro Missir di Lusignano Publications d’IKV No : 225 La Turquie et L’Europe - Un Exemple: ALESSANDRO MISSIR di LUSIGNANO English Translation Laura Austrums, BELGIUM Couverture réalisée par Sümbül Eren Conception et réalisation: Rauf Kösemen, Myra Superviseur du project: Damla Özlüer Mise en page Gülderen R. Erbaş, Harun Yılmaz,Myra Merci aux photographes : Giada Ripa de Meana (www.giadaripa.net) et Caner Kasapoğlu (www.canerkasapoglu.com) pour leurs superbes photos d’Istanbul. Les photos sans droits d’auteur ou détails spécifiques ont été prises par Letizia Missir di Lusignano Impression Acar Basım ve Cilt Sanayi A.Ş. Beysan Sanayi Sit. Birlik Cad. No. 26 Acar Binası 34524 Haramidere/Avcılar/Istanbul/Türkiye Tel: +90 212 422 18 34 Fax: +90 212 422 17 86 Première Edition, Septembre 2009 ISBN 978-605-5984-18-2 Copyright © IKV Tous droits réservés Livre hors commerce. LA FONDATION POUR LE DEVELOPPEMENT ECONOMIQUE La Turquie et L’Europe - Un Exemple: ALESSANDRO MISSIR di LUSIGNANO SIEGE OFFICIEL Talatpaşa Caddesi Alikaya Sokak TOBB Plaza No : 3 Kat : 7-8 34394 Levent Istanbul – TURQUIE Tel: 00 90 212 270 93 00 Fax: 00 90 212 270 30 22 [email protected] BUREAU de BRUXELLES Avenue Franklin Roosevelt 148/A 1000 Bruxelles – BELGIQUE Tel: 00 32 2 646 40 40 Fax: 00 32 2 646 95 38 [email protected] Textes et témoignages collectés et coordonnés par Letizia Missir di Lusignano et Melih Özsöz, La Fondation pour le Développement Economique. Coordinateur administratif : M. Haluk Nuray, La Fondation pour le Développement Economique Nos remerciements particuliers à Bahadır Kaleağası pour son soutien dans le sponsoring de la traduction anglaise de ce livre. -

Reading Congo Reform Literature: Humanitarianism and Form in the Edwardian Era

READING CONGO REFORM LITERATURE: HUMANITARIANISM AND FORM IN THE EDWARDIAN ERA A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English By Mary K. Galli, B.A. Washington, D.C. April 15, 2019 Copyright 2019 by Mary K. Galli All Rights Reserved ii READING CONGO REFORM LITERATURE: HUMANITARIANISM AND FORM IN THE EDWARDIAN ERA Mary K. Galli, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Cóilín Parsons, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Social and political upheaval was ubiquitous at the turn of the twentieth century. The death of Queen Victoria in 1901 and King Edward VII’s subsequent ascension created a transitional moment that ended around the time of Edward’s death in 1910. Narrative form during the Edwardian era reflects the transitional nature of the time. In this thesis, I analyze the literary forms that authors used to address imperial violence and the atrocities committed in King Leopold II of Belgium’s Congo Free State (1885-1908). Joseph Conrad’s 1899 modernist novella, Heart of Darkness, predated the Congo Reform Association (1904-1912), but significantly influenced the reform movement, which is often identified as the first modern human rights and first mass media campaign. While Conrad’s modernist form differs from Mark Twain’s 1905 satirical pamphlet, King Leopold’s Soliloquy, and from Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1909 nonfiction, The Crime of the Congo, I argue that the diverse forms of these three texts delay the reading experience, which creates time for the reader (and possibly the writer) to think about the atrocities in the Congo, who to blame, and how to respond. -

BRUSSELS © Shopping, Consistently Excellentdiningatallpriceranges,Sublimechocolate Shops Anda the Trulygrandgrandplaceissurely Oneoftheworld’Smostbeautiful Squares

© Lonely Planet 62 Brussels BRUSSELS BRUSSELS The fascinating capital of Belgium and Europe sums up all the contradictions of both. It’s simultaneously historic yet hip, bureaucratic yet bizarre, self confident yet un-showy and multicultural to its roots. The city’s contrasts and tensions are multilayered yet somehow consistent in their very incoherence – Francophone versus Flemish, Bruxellois versus Belgian versus Eurocrat versus immigrant. And all this plays out on a cityscape that swings block by block from majestic to quirky to grimily rundown and back again. It’s a complex patchwork of overlapping yet distinctive neighbourhoods that takes time to understand. Organic art nouveau facades face off against 1960s concrete disgraces. Regal 19th-century mansions contrast with the brutal glass of the EU’s real-life Gotham City. World-class museums lie hidden in suburban parks and a glorious beech forest extends extraordinarily deep into the city’s southern flank. This whole maelstrom swirls forth from Brussels’ medieval core, where the truly grand Grand Place is surely one of the world’s most beautiful squares. Constant among all these disparate images is the enviable quality of everyday life – great shopping, consistently excellent dining at all price ranges, sublime chocolate shops and a café scene that could keep you drunk for years. But Brussels doesn’t go out of its way to impress. Its citizens have a low-key approach to everything. And their quietly humorous, deadpan outlook on life is often just as surreal as the classic Brussels-painted -

Lessons from the History of the Congo Free State

BLOCHER &G ULATI IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 2/16/2020 7:11 PM Duke Law Journal VOLUME 69 MARCH 2020 NUMBER 6 TRANSFERABLE SOVEREIGNTY: LESSONS FROM THE HISTORY OF THE CONGO FREE STATE JOSEPH BLOCHER & MITU GULATI† ABSTRACT In November 1908, the international community tried to buy its way out of the century’s first recognized humanitarian crisis: King Leopold II’s exploitation and abuse of the Congo Free State. And although the oppression of Leopold’s reign is by now well recognized, little attention has been paid to the mechanism that ended it—a purchased transfer of sovereign control. Scholars have explored Leopold’s exploitative acquisition and ownership of the Congo and their implications for international law and practice. But it was also an economic transaction that brought the abuse to an end. The forced sale of the Congo Free State is our starting point for asking whether there is, or should be, an exception to the absolutist conception of territorial integrity that dominates traditional international law. In particular, we ask whether oppressed regions should have a right to exit—albeit perhaps at a price—before the relationship between the sovereign and the region deteriorates to the level of genocide. Copyright © 2020 Joseph Blocher & Mitu Gulati. † Faculty, Duke Law School. For helpful comments and criticism, we thank Tony Anghie, Stuart Benjamin, Jamie Boyle, Curt Bradley, George Christie, Walter Dellinger, Deborah DeMott, Laurence Helfer, Tim Lovelace, Ralf Michaels, Darrell Miller, Shitong Qiao, Steve Sachs, Alex Tsesis, and Michael Wolfe. Rina Plotkin provided invaluable research and linguistic support, Jennifer Behrens helped us track down innumerable difficult sources, and the editors of the Duke Law Journal delivered exemplary edits and suggestions. -

Review Essay Stephen A

Naval War College Review Volume 62 Article 10 Number 1 Winter 2009 Review Essay Stephen A. Emerson Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Emerson, Stephen A. (2009) "Review Essay," Naval War College Review: Vol. 62 : No. 1 , Article 10. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol62/iss1/10 This Additional Writing is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Emerson: Review Essay REVIEW ESSAY THE ESSENTIAL AFRICA READER Stephen A. Emerson Dr. Stephen A. Emerson is an African-affairs specialist Morris, Donald R. TheWashingoftheSpears:TheRiseand with over twenty-five years of experience working on Fall of the Zulu Nation.NewYork:Simon&Schuster, African political and security issues. He currently 1965. 650pp. $25.15 teaches security, strategy, and forces (SSF) and strategy Moorehead, Alan. The White Nile.NewYork:Harperand and theater security (STS) at the Naval War College. Prior to joining the NWC faculty, Emerson worked for Row, 1960. 448pp. $14.95 the U.S. Department of Defense as a political-military Pakenham, Thomas. The Scramble for Africa: White Man’s analyst for southern Africa, and was Chair of Security Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876–1912.New Studies at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies. His York: Random House, 1994. 738pp. $23.95 professional interests include southern African studies, Hochschild, Adam. -

An Examination of the Instability and Exploitation in Congo from King Leopold II's Free State to the 2Nd Congo War

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Central Florida (UCF): STARS (Showcase of Text, Archives, Research & Scholarship) University of Central Florida STARS HIM 1990-2015 2014 An Examination of the Instability and Exploitation in Congo From King Leopold II's Free State to the 2nd Congo War Baldwin Beal University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIM 1990-2015 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Beal, Baldwin, "An Examination of the Instability and Exploitation in Congo From King Leopold II's Free State to the 2nd Congo War" (2014). HIM 1990-2015. 1655. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015/1655 AN EXAMINATION OF THE INSTABILITY AND EXPLOITATION IN CONGO FROM KING LEOPOLD II’S FREE STATE TO THE 2ND CONGO WAR by BALDWIN J. BEAL A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in History in the College of Arts and Humanities and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2014 Thesis Chair: Dr. Ezekiel Walker Abstract This thesis will analyze the Congo from King Leopold II’s Free State to the 2nd Congo War. After a thorough investigation of the colonial period, this thesis will analyze the modern period. -

“Alpe,” the Magnificat Number 18

Encounters in Theory and History of Education Vol. 18, 2017 By María Cruz Bascones “Alpe,” The MagniFicat Number 18 ISSN 2560-8371 Ó Encounters in Theory and History of Education 1 Encounters in Theory and History of Education Vol. 18, 2017, 2-26 Colonial education in the Congo - a question oF “uncritical” pedagogy until the bitter end? La educación colonial en el Congo, ¿una cuestión de pedagogía "acrítica" hasta el amargo Final? L’éducation coloniale au Congo – une question de pédagogie « non-critique» jusqu’à la fin? Marc Depaepe KULeuven@Kulak, Belgium ABSTRACT Our approach is a historical, and not a theoretical or a philosophical one. But such an approach might help in understanding the complexities and ambiguities of the pedagogical mentalities in the course of the twentieth century. As is usually the case in historical research, the groundwork must precede the formulation of hypotheses, let alone theories, about the nature of pedagogical practices. Therefore, since the 1990s, “we” (as a team) have been busy studying the history of education in the former Belgian Congo. Of course, since then we have not only closely monitored the theoretical and methodological developments in the field of colonial historiography, but have ourselves also contributed to that history. This article tries to give an overview of some of our analyses, concentrating on the question of to what extent the Belgian offensive of colonial (i.e. mainly Catholic) missionary education, which was almost exclusively targeted at “paternalism,” contributed to the development of a personal life, individual autonomy and/or emancipation of the native people. From the rear-view mirror of history we are, among other things, zooming in on the crucial 1950s, during which decade thoughts first turned to the education of a (very limited) “elite.” The thesis we are using in this respect is that the nature of the “mental space” of colonialism was such that it did not engender a very great widening of consciousness among the local population.