Lessons from the History of the Congo Free State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Silent Crisis in Congo: the Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika

CONFLICT SPOTLIGHT A Silent Crisis in Congo: The Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika Prepared by Geoffroy Groleau, Senior Technical Advisor, Governance Technical Unit The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), with 920,000 new Bantus and Twas participating in a displacements related to conflict and violence in 2016, surpassed Syria as community 1 meeting held the country generating the largest new population movements. Those during March 2016 in Kabeke, located displacements were the result of enduring violence in North and South in Manono territory Kivu, but also of rapidly escalating conflicts in the Kasaï and Tanganyika in Tanganyika. The meeting was held provinces that continue unabated. In order to promote a better to nominate a Baraza (or peace understanding of the drivers of the silent and neglected crisis in DRC, this committee), a council of elders Conflict Spotlight focuses on the inter-ethnic conflict between the Bantu composed of seven and the Twa ethnic groups in Tanganyika. This conflict illustrates how representatives from each marginalization of the Twa minority group due to a combination of limited community. access to resources, exclusion from local decision-making and systematic Photo: Sonia Rolley/RFI discrimination, can result in large-scale violence and displacement. Moreover, this document provides actionable recommendations for conflict transformation and resolution. 1 http://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2017/pdfs/2017-GRID-DRC-spotlight.pdf From Harm To Home | Rescue.org CONFLICT SPOTLIGHT ⎯ A Silent Crisis in Congo: The Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika 2 1. OVERVIEW Since mid-2016, inter-ethnic violence between the Bantu and the Twa ethnic groups has reached an acute phase, and is now affecting five of the six territories in a province of roughly 2.5 million people. -

Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate

Freistaat Sachsen State Chancellery Message and Greeting ................................................................................................................................................. 2 State and People Delightful Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate ......................................................................................... 5 The Saxons – A people unto themselves: Spatial distribution/Population structure/Religion .......................... 7 The Sorbs – Much more than folklore ............................................................................................................ 11 Then and Now Saxony makes history: From early days to the modern era ..................................................................................... 13 Tabular Overview ........................................................................................................................................................ 17 Constitution and Legislature Saxony in fine constitutional shape: Saxony as Free State/Constitution/Coat of arms/Flag/Anthem ....................... 21 Saxony’s strong forces: State assembly/Political parties/Associations/Civic commitment ..................................... 23 Administrations and Politics Saxony’s lean administration: Prime minister, ministries/State administration/ State budget/Local government/E-government/Simplification of the law ............................................................................... 29 Saxony in Europe and in the world: Federalism/Europe/International -

General Observations About the Free State Provincial Government

A Better Life for All? Fifteen Year Review of the Free State Provincial Government Prepared for the Free State Provincial Government by the Democracy and Governance Programme (D&G) of the Human Sciences Research Council. Ivor Chipkin Joseph M Kivilu Peliwe Mnguni Geoffrey Modisha Vino Naidoo Mcebisi Ndletyana Susan Sedumedi Table of Contents General Observations about the Free State Provincial Government........................................4 Methodological Approach..........................................................................................................9 Research Limitations..........................................................................................................10 Generic Methodological Observations...............................................................................10 Understanding of the Mandate...........................................................................................10 Social attitudes survey............................................................................................................12 Sampling............................................................................................................................12 Development of Questionnaire...........................................................................................12 Data collection....................................................................................................................12 Description of the realised sample.....................................................................................12 -

World Bank Document

AID AND REFORM THE CASE OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO Public Disclosure Authorized TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract 2 Introduction 3 Part One: Economic Policy and Performance 3 The chaotic years following independence 3 The early Mobutu years 4 Public Disclosure Authorized The shocks of 1973-75 4 The recession years and early attempts at reform 5 The 1983 reform 5 Renewed fiscal laxity 5 The promise of structural reforms 6 The last attempt 7 Part Two: Aid and Reform 9 Financial flows and reform 9 Adequacy of the reform agenda 10 Public resource management 12 Public Disclosure Authorized The political dimension of reform 13 Conclusion 14 This paper is a contribution to the research project initiated by the Development Research Group of the World Bank on Aid and Reform in Africa. The objective of the study is to arrive at a better understanding of the causes of policy reforms and the foreign aid-reform link. The study is to focus on the real causes of reform and if and how aid in practice has encouraged, generated, influenced, supported or retarded reforms. A series of country case studies were launched to achieve the objective of the research project. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) was selected among nine other countries in Africa. The case study has been conducted by a team of two researchers, including Public Disclosure Authorized Gilbert Kiakwama, who was Congo’s Minister of Finance in 1983-85, and Jerome Chevallier. AID AND REFORM The case of the Democratic Republic of Congo ABSTRACT. i) During its first years of independence, the Democratic Republic of the Congo plunged into anarchy and became a hot spot in the cold war between the Soviet Union and the West. -

The Free State, South Africa

Higher Education in Regional and City Development Higher Education in Regional and City Higher Education in Regional and City Development Development THE FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICA The third largest of South Africa’s nine provinces, the Free State suffers from The Free State, unemployment, poverty and low skills. Only one-third of its working age adults are employed. 150 000 unemployed youth are outside of training and education. South Africa Centrally located and landlocked, the Free State lacks obvious regional assets and features a declining economy. Jaana Puukka, Patrick Dubarle, Holly McKiernan, How can the Free State develop a more inclusive labour market and education Jairam Reddy and Philip Wade. system? How can it address the long-term challenges of poverty, inequity and poor health? How can it turn the potential of its universities and FET-colleges into an active asset for regional development? This publication explores a range of helpful policy measures and institutional reforms to mobilise higher education for regional development. It is part of the series of the OECD reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. These reviews help mobilise higher education institutions for economic, social and cultural development of cities and regions. They analyse how the higher education system T impacts upon regional and local development and bring together universities, other he Free State, South Africa higher education institutions and public and private agencies to identify strategic goals and to work towards them. CONTENTS Chapter 1. The Free State in context Chapter 2. Human capital and skills development in the Free State Chapter 3. -

A Lagrangian Perspective of the Hydrological Cycle in the Congo River Basin Rogert Sorí1, Raquel Nieto1,2, Sergio M

Earth Syst. Dynam. Discuss., doi:10.5194/esd-2017-21, 2017 Manuscript under review for journal Earth Syst. Dynam. Discussion started: 9 March 2017 c Author(s) 2017. CC-BY 3.0 License. A Lagrangian Perspective of the Hydrological Cycle in the Congo River Basin Rogert Sorí1, Raquel Nieto1,2, Sergio M. Vicente-Serrano3, Anita Drumond1, Luis Gimeno1 1 Environmental Physics Laboratory (EphysLab), Universidade de Vigo, Ourense, 32004, Spain 5 2 Department of Atmospheric Sciences, Institute of Astronomy, Geophysics and Atmospheric Sciences, University of SãoPaulo, São Paulo, 05508-090, Brazil 3 Instituto Pirenaico de Ecología, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (IPE-CSIC), Zaragoza, 50059, Spain Correspondence to: Rogert Sorí ([email protected]) Abstract. 10 The Lagrangian model FLEXPART was used to identify the moisture sources of the Congo River Basin (CRB) and investigate their role in the hydrological cycle. This model allows us to track atmospheric parcels while calculating changes in the specific humidity through the budget of evaporation-minus-precipitation. The method permitted the identification at an annual scale of five continental and four oceanic regions that provide moisture to the CRB from both hemispheres over the course of the year. The most important is the CRB itself, providing more than 50% of the total atmospheric moisture income to the basin. Apart 15 from this, both the land extension to the east of the CRB together with the ocean located in the eastern equatorial South Atlantic Ocean are also very important sources, while the Red Sea source is merely important in the budget of (E-P) over the CRB, despite its high evaporation rate. -

Colonialism and Its Socio-Politico and Economic Impact: a Case Study of the Colonized Congo Gulzar Ahmad & Muhamad Safeer Awan

Colonialism and its Socio-politico and Economic Impact: A Case study of the Colonized Congo Gulzar Ahmad & Muhamad Safeer Awan Abstract The exploitation of African Congo during colonial period is an interesting case study. From 1885 to 1908, it remained in the clutches of King Leopold II. During this period the Congo remained a victim of exploitation which has far sighted political, social and economic impacts. The Congo Free State was a large state in Central Africa which was in personal custody of King Leopold II. The socio-politico and economic study of the state reflects the European behaviour and colonial policy, a point of comparison with other colonial experiences. The analysis can be used to show that the abolition of the slave trade did not necessarily lead to a better experience for Africans at the hands of Europeans. It could also be used to illustrate the problems of our age. The social reformers, political leaders; literary writers and the champion of human rights have their own approaches and interpretations. Joseph Conrad is one of the writers who observed the situation and presented them in fictional and historical form in his books, Heart of Darkness, The Congo Diary, Notes on Life and Letters and Personal Record. In this paper a brief analysis is drawn about the colonialism and its socio-political and psychological impact in the historical perspectives. Keywords: Colonialism, Exploitation, Colonialism, Congo. Introduction The state of Congo, the heart of Africa, was colonized by Leopold II, king of the Belgium from 1885 to 1908. During this period it remained in the clutches of colonialism. -

Democratic Republic of Congo: Background and U.S

Democratic Republic of Congo: Background and U.S. Relations name redacted Specialist in African Affairs July 5, 2018 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R43166 Democratic Republic of Congo: Background and U.S. Relations Summary Since the 2003 conclusion of “Africa’s World War”—a conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) that drew in neighboring countries and reportedly caused millions of deaths—the United States and other donors have focused substantial resources on stabilizing the country. Smaller-scale insurgencies have nonetheless persisted in DRC’s densely-inhabited, mineral-rich eastern provinces, causing regional instability and a long-running humanitarian crisis. In recent years, political uncertainty at the national level has sparked new unrest. Elections due in 2016 have been repeatedly delayed, leaving President Joseph Kabila—who is widely unpopular—in office well past the end of his second five-year term. State security forces have brutally cracked down on anti-Kabila street protests. Armed conflicts have worsened in the east, while new crises have emerged in previously stable areas such as the central Kasai region and southeastern Tanganyika province. An Ebola outbreak in early 2018 added to the country’s humanitarian challenges, although it appears likely to be contained. The Trump Administration has maintained a high-level concern with human rights abuses and elections in DRC. It has simultaneously altered the U.S. approach in some ways by eliminating a senior Special Envoy position created under the Obama Administration and securing a reduction in the U.N. peacekeeping operation in DRC (MONUSCO). The United States remains the largest humanitarian donor in DRC and the largest financial contributor to MONUSCO. -

Addressing Belgium's Crimes in the Congo Free State

Historical Security Council Addressing Belgium's crimes in the Congo Free State Director: Mauricio Quintero Obelink Moderator: Arantxa Marin Limón INTRODUCTION The Security Council is one of the six main organs of the United Nations. Its five principle purposes are to “maintain international peace and security, to develop diplomatic relations among nations, to cooperate in solving international problems, promote respect for human rights, and to be a centre for harmonizing the actions of nations” (What is the Security Council?, n.d.). The Committee is made up of 10 elected members and 5 permanent members (China, France, Russian Federation, United Kingdom, United States), all of which have veto power, which ultimately allows them to block proposed resolutions. As previously mentioned, the Security Council focuses on international matters regarding diplomatic relations, as well as the establishment of human rights protocols. For this reason, Belgium’s occupation of the greater Congo area is a topic of relevance within the committee. The Congo Free State was a large territory in Africa established by the Belgian Crown in 1885, and lasted until 1908. It was created after Leopold II commissioned European investors to explore and establish the land as European territory in order to gain international, economic; and political power. When the Belgian military gained power over the Congo territory, natives included, inhumane crimes were committed towards the inhabitants, all while under Leopold II’s supervision and approval. For this reason, King Leopold II’s actions, as well as the direct crimes committed by his army, must be held accountable in order to bring justice to the territory and its people. -

Kitona Operations: Rwanda's Gamble to Capture Kinshasa and The

Courtesy of Author Courtesy of Author of Courtesy Rwandan Patriotic Army soldiers during 1998 Congo war and insurgency Rwandan Patriotic Army soldiers guard refugees streaming toward collection point near Rwerere during Rwanda insurgency, 1998 The Kitona Operation RWANDA’S GAMBLE TO CAPTURE KINSHASA AND THE MIsrEADING OF An “ALLY” By JAMES STEJSKAL One who is not acquainted with the designs of his neighbors should not enter into alliances with them. —SUN TZU James Stejskal is a Consultant on International Political and Security Affairs and a Military Historian. He was present at the U.S. Embassy in Kigali, Rwanda, from 1997 to 2000, and witnessed the events of the Second Congo War. He is a retired Foreign Service Officer (Political Officer) and retired from the U.S. Army as a Special Forces Warrant Officer in 1996. He is currently working as a Consulting Historian for the Namib Battlefield Heritage Project. ndupress.ndu.edu issue 68, 1 st quarter 2013 / JFQ 99 RECALL | The Kitona Operation n early August 1998, a white Boeing remain hurdles that must be confronted by Uganda, DRC in 1998 remained a safe haven 727 commercial airliner touched down U.S. planners and decisionmakers when for rebels who represented a threat to their unannounced and without warning considering military operations in today’s respective nations. Angola had shared this at the Kitona military airbase in Africa. Rwanda’s foray into DRC in 1998 also concern in 1996, and its dominant security I illustrates the consequences of a failure to imperative remained an ongoing civil war the southwestern Bas Congo region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). -

Arnesen CV GWU Website June 2009

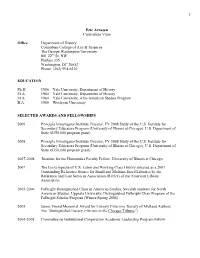

1 Eric Arnesen Curriculum Vitae Office Department of History Columbian College of Arts & Sciences The George Washington University 801 22nd St. NW Phillips 335 Washington, DC 20052 Phone: (202) 994-6230 EDUCATION Ph.D. 1986 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Afro-American Studies Program B.A. 1980 Wesleyan University SELECTED AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS 2009 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2008 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2007-2008 Institute for the Humanities Faculty Fellow, University of Illinois at Chicago 2007 The Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working Class History selected as a 2007 Outstanding Reference Source for Small and Medium-Sized Libraries by the Reference and User Services Association (RUSA) of the American Library Association. 2005-2006 Fulbright Distinguished Chair in American Studies, Swedish Institute for North American Studies, Uppsala University, Distinguished Fulbright Chair Program of the Fulbright Scholar Program (Winter-Spring 2006) 2005 James Friend Memorial Award for Literary Criticism, Society of Midland Authors (for “distinguished literary criticism in the Chicago Tribune”) 2004-2005 Committee on Institutional -

Commission Federale Des Officiels Techniques

COMMISSION FEDERALE DES OFFICIELS TECHNIQUES Nominations des arbitres français sur les compétitions internationales 2019, au 04 octobre 2019 Niveau Dates Tournoi Lieu Arbitre ou UM désigné Compétition 08-13 janv Thailand Masters Bangkok BWF Super 300 MESTON François 10-13 janv Estonian International Tallinn Int. Series LAPLACE Patrick 17-20 janv Swedish Open Lund Int. Series DAMANY Xavier 22-27 janv Indonesia Masters Jakarta BWF Super 500 VENET Stéphane 15-17 fév Spanish Junior Oviedo Junior Int. Series VIOLLETTE Gilles 15-17 fév France U17 Open Aire sur la Lys BEC-U17 voir liste 19-24 fév Spain Masters Barcelone BWF Super 300 RUCHMANN Emilie 22-24 fév Italian Junior Milan Junior Int. Series LOYER Julie 26 fév - 03 mars German Open Muelheim an der Ruhr BWF Super 300 BERTIN Véronique Junior Int. Grand 27 fév-03 mars Dutch Junior Haarlem DAMANY Xavier Prix 06-10 mars All England Open Birmingham BWF Super 1000 DITTOO Haidar 07-10 mars Portuguese International Caldas da Rainha Int. Series MATON Evelyne Junior Int. Grand 07-10 mars German Junior Berlin LAPLACE Patrick Prix 12-17 mars Swiss Open Bâle BWF Super 300 SAUVAGE Micheline 19-24 mars Orléans Masters Orléans BWF Super 100 voir liste 26-31 mars India Open New Delhi BWF Super 500 GOUTTE Michel 28-31 mars Polish Open Czestochowa Int. Challenge STRADY Jean-Pierre FAUVET Antoine 04-07 avril Finnish Open Vantaa Int. Challenge COUVAL Sébastien (Assessment) 11-14 avril Dutch International Wateringen Int. Series DELCROIX Claude 18-21 avril Croatian International Zagreb Future Series JOSSE Stéphane 09-12 mai Denmark Challenge Farum Int.