(Parmananda) in Hindi Film Adaptations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Oscar-Winning 'Slumdog Millionaire:' a Boost for India's Global Image?

ISAS Brief No. 98 – Date: 27 February 2009 469A Bukit Timah Road #07-01, Tower Block, Singapore 259770 Tel: 6516 6179 / 6516 4239 Fax: 6776 7505 / 6314 5447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.isas.nus.edu.sg Oscar-winning ‘Slumdog Millionaire’: A Boost for India’s Global Image? Bibek Debroy∗ Culture is difficult to define. This is more so in a large and heterogeneous country like India, where there is no common language and religion. There are sub-cultures within the country. Joseph Nye’s ‘soft power’ expression draws on a country’s cross-border cultural influences and is one enunciated with the American context in mind. Almost tautologically, soft power implies the existence of a relatively large country and the term is, therefore, now also being used for China and India. In the Indian case, most instances of practice of soft power are linked to language and literature (including Indians writing in English), music, dance, cuisine, fashion, entertainment and even sport, and there is no denying that this kind of cross-border influence has been increasing over time, with some trigger provided by the diaspora. The film and television industry’s influence is no less important. In the last few years, India has produced the largest number of feature films in the world, with 1,164 films produced in 2007. The United States came second with 453, Japan third with 407 and China fourth with 402. Ticket sales are higher for Bollywood than for Hollywood, though revenue figures are much higher for the latter. Indian film production is usually equated with Hindi-language Bollywood, often described as the largest film-producing centre in the world. -

India Abroad Person of the Year 2010 Awards Honor Community’S Stars

PERIODICAL INDEX Letters to the Editor......................................A2 People..............................................................A4 Immigration.................................................A32 Business.......................................................A30 Community...................................................A36 Magazine......................................................M1 Sports............................................................A35 Friday, July 8, 2011 Vol. XLI No. 41 www.rediff.com (Nasdaq: REDF) NEW YORK EDITION $1 Pages: 44+24=68 International Weekly Newspaper Chicago/Dallas Los Angeles NY/NJ/CT New York Toronto The Best of Us INDIA ABROAD PERSON OF THE YEAR 2010 AWARDS HONOR COMMUNITY’S STARS PARESH GANDHI To subscribe 1-877-INDIA-ABROAD (1-877-463-4222) www.indiaabroad.com/subscribe ADVERTISEMENT The International Weekly Newspaper founded in 1970. A India Abroad July 8, 2011 Member, Audit Bureau of Circulation 241 LETTERS INDIA ABROAD (ISSN 0046 8932) is published every Friday by India Abroad Publications, Inc. 42 Broadway, 18th floor, New York, NY 10004. Annual subscription in United States: $32. Canada $26. India $32 INTERNATIONAL: it because this fast is being undertaken bill is passed. The whole credit will go to By Regular Mail: South America, the Caribbean, Europe, Africa, Australia & Middle How can India by a ‘religious’ person, though the him and to the members of parliament. East: $90. By Airmail: South America, the Caribbean, Europe, Africa, Australia & Middle East: surpass China? objective of this hunger strike is similar Indian history will not be complete with- $210 Periodical postage paid, New York, NY and at additional mailing offices. to that of activist Anna Hazare? out Singh’s name figuring prominently in Postmaster: Send address changes to: With the recent economic growth in The fast by Baba Ramdev is no differ- it. INDIA ABROAD, 42 Broadway 18th floor, New York, NY 10004 Copyright (c) 2006, India Abroad Publications, Inc. -

Universidade Federal Do Rio De Janeiro Faculdade De Letras Comissão De Pós-Graduação E Pesquisa

Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Faculdade de Letras Comissão de Pós-Graduação e Pesquisa DA TRADUÇÃO/ADAPTAÇÃO COMO PRÁTICA TRANSCULTURAL: UM OLHAR SOBRE O HAMLET EM TERRAS ESTRANGEIRAS Marcel Alvaro de Amorim Rio de Janeiro Março de 2016 Marcel Alvaro de Amorim DA TRADUÇÃO/ADAPTAÇÃO COMO PRÁTICA TRANSCULTURAL: UM OLHAR SOBRE O HAMLET EM TERRAS ESTRANGEIRAS Tese de Doutorado apresentada ao Programa Interdisciplinar de Pós-Graduação em Linguística Aplicada da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, como parte dos requisitos necessários para a obtenção do Título de Doutor em Linguística Aplicada. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Roberto Ferreira da Rocha Rio de Janeiro Março de 2016 A524d Amorim, Marcel Alvaro de Da tradução/adaptação como prática transcultural: um olhar sobre o Hamlet em terras estrangeiras / Marcel Alvaro de Amorim. — Rio de Janeiro: UFRJ, 2016. 183 f.; 30 cm Orientador: Roberto Ferreira da Rocha. Tese (Doutorado) - Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Faculdade de Letras, Pós-Graduação em Linguística Aplicada, 2016. Bibliografia: 165-175 1. Cinema. 2. Literatura. 3. Hamlet. 4. Shakespeare, William, 1564-1616. I. Rocha, Roberto Ferreira da. II. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Faculdade de Letras. III. Título. CDD 791.43 DEDICATÓRIA A construção desta Tese foi (e continua a ser) um trabalho dialógico, em que várias vozes dialogaram (e ainda dialogam) na tentativa de construção de modos de se ler o ‘Hamlet’, de William Shakespeare, em territórios estrangeiros. No entanto, duas, dentre todas as vozes aqui refratadas, foram essenciais para o desenvolvimento da pesquisa: as vozes (e todos os discursos a elas relacionadas) de meu orientador de doutorado, Prof. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

An Imaginative Film and Monumental by Its Production Values and Cinematic Brilliance in Creating a Fantasy World on Screen

63rd NATIONAL FILM AWARDS FOR 2015 FEATURE FILMS S.No. Name of Award Name of Film Awardees Medal Citation & Cash Prize 1. BEST FEATURE BAAHUBALI Producer: SHOBU Swarna Kamal An imaginative film and FILM YARLAGADDA AND and monumental by its production ARKA values and cinematic brilliance MEDIAWORKS (P) 2,50,000/- LTD. each to in creating a fantasy world on screen. the Producer and Director : S.S Director RAJAMOULI (CASH COMPONENT TO BE SHARED) 2. INDIRA GANDHI MASAAN Producer: Swarna Kamal For his perceptive approach AWARD FOR BEST PHANTOM FILMS and to filmmaking in handling a DEBUT FILM OF A layered story of DIRECTOR Director : NEERAJ 1,25, 000/- people caught up changing GHAYWAN each to social and moral values. the Producer and Director 3. BEST POPULAR BAJRANGI Producer: SALMA Swarna Kamal Tackling an important social FILM PROVIDING BHAIJAAN KHAN, and issue in the simple heart- WHOLESOME SALMAN KHAN, warming & entertaining format. ENTERTAINMENT ROCKLINE 2,00,000/- VENKTESH each to Director : KABIR the Producer and KHAN Director 4. NARGIS DUTT NANAK SHAH Producer: Rajat Kamal and The saga on the life of the FAKIR GURBANI MEDIA AWARD FOR great spiritual master BEST FEATURE PVT. LTD. 1,50,000/- each to advocating the values of peace FILM ON and harmony. NATIONAL the Producer and INTEGRATION Director 5. BEST FILM ON NIRNAYAKAM Producer: JAIRAJ Rajat Kamal and For tackling a relevant and SOCIAL ISSUES FILMS unaddressed issue of 1,50,000/- each curtailing freedom of Director : V.K to movement for the common PRAKASH the Producer and man due to hartals and Director processions. -

Page 01 Dec 31.Indd

ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED NEWSPAPER Opec output hits six-month low on Libya Business | 17 Wednesday 31 December 2014 • 9 Rabial I 1436 • Volume 19 Number 6296 www.thepeninsulaqatar.com [email protected] | [email protected] Editorial: 4455 7741 | Advertising: 4455 7837 / 4455 7780 Stop closure of Deputy Emir awards camel race winners OPINION Gulf and the petrol stations, oil crisis s it the Ibegin- ning of says civic body the end or end of the begin- ning? Ten facilities already shut down Whatever inter- DOHA: The Central Municipal offered various services in just a preta- Council (CMC) yesterday raised small place — services like car- tions and Dr Khalid Al Jaber the issue of shortage of petrol wash and tyre change. analyses stations and urged the civic Then, there were people who experts might offer on the ministry to stop shutting down come to the petrol station to buy steep decline in oil prices, these stations, especially in refreshments and transparent there is no doubt that the densely populated areas. cooking gas cylinders. current crisis is causing The CMC said there was a need Al Hajri suggested that the alarm about the future of to conduct studies to assess the government come out with some this most important stra- requirement of petrol stations in solutions like moving the above tegic commodity and its different localities and take meas- services. “A petrol station should impact on the Gulf States in ures to increase their number. be reserved only for refuelling The Deputy Emir H H Sheikh Abdullah bin Hamad Al Thani awarding the winner of the Founder Sheikh particular. -

Movies of Feroz Khan

1 / 2 Movies Of Feroz Khan Feroze Khan (born July 11, 1990) is famous for being tv actor. ... Padmavati is undeniably the most awaited movie of the year and it won't be hard to call it a hit .... Feroz Khan Movies List. Thambi Arjuna (2010)Ramana, Aashima. Welcome (2007)Feroz Khan, Anil Kapoor. Ek Khiladi Ek Haseena (2005)Fardeen Khan, .... See more ideas about actors, pakistani actress, feroz khan. ... Khushbo is Pakistani film and stage Actress. c) On some minimal productions (e. Want to Become .... Tasveer Full Hindi Movie (1966) Film cast : Feroz Khan, Kalpana, Helen, Sajjan, Rajendra Nath, Nazir Hasain, Leela Mishra, Raj Mehra, Lalita Pawar, Sabeena. MUMBAI, India (Agence France-Presse) — Feroz Khan, a Bollywood ... he made “Dharmatma,” the first Hindi-language movie shot on location .... Actor Rishi Kapoor tweeted that the two actors, who worked together in three films, died of Cancer on the same date. Known for his flamboyant persona, Feroz Khan was an actor, director and producer who had a long innings in the Hindi film industry. The actor .... Feroz Khan was born at Bangalore in India to an Afghan Father, Sadiq Khan and an Iranian mother Fatima. After schooling from Bangalore he shifted to Bombay .... He would have turned 79 on September 25. However, actor, director and producer Feroz Khan – one of his kind in the Hindi film industry .... Feroz Khan All Movies List · Ek Khiladi Ek Haseena - 2005 · Ek Khiladi Ek Haseena (2005)Feroz Khan , Fardeen Khan , Koena Mitra , Gulshan Grover , Kay Kay , .... India's answer to Clint Eastwood, Feroz Khan is known as the most stylish bollywood actor. -

Shakespeare Wallah

Shakespeare and Film 1910 The film The shortest The film adaptation 1913 Taming of of Hamlet, only the Shrew, 59 minutes, was starring released. 1929 Mary Pickford & Douglas Fairbanks, was the first ‘talkie’ version of a Khoon Ka Khoon (Blood Shakespeare play. for Blood) or Hamlet, 1930 directed by Sohrab Modi, was the first Hindi/Urdu sound film adaptation of a Shakespeare play. 1935 The adaptation 1936 of As You Like It The first television marked the first broadcast of Shakespeare appearance 1937 was on 5 February 1937. of Laurence The BBC broadcast an Olivier as a character in a 11-minute scene from Shakespearean film. As You Like It, starring Margaretta Scott as Rosalind and Ion 1940 Swinley as Orlando. Laurence Olivier’s adaptation of Henry V 1944 was an attempt to boost morale and patriotism “This is the during the Second World War. tragedy of a 1948 man who could not make up his mind…” —From the spoken prologue of Laurence Olivier’s version of Hamlet. 1950 1952 Orson Welles directed “Look upon the ruins/ Of and starred in his film the castle of delusion.” adaptation of Othello. —Lines from the prologue 1957 of the Japanese adaptation of The Bad Sleep Well, a Macbeth, Japanese film involving Kumonosu-jÔ 1960 corporate greed and (Throne of Blood). vengeance, is released as a loose adaptation 1960 of Hamlet. Shakespeare Wallah, though not an adaptation of a play, features a fictional theater troupe The Swedish film Elvira in India that performs 1965 Madigan was reminiscent Shakespeare plays in of Romeo and Juliet, towns across the nation. -

Shakespeare on Indian Floorboards and Hindi

SHAKESPEARE ON INDIAN FLOORBOARDS AND HINDI CINEMA:EVOLUTION AND RELATION *Rupali Chaudhary (Ph.D Research Scholar) Department of Journalism and Mass Communication Punjabi University, Patiala (India) ABSTRACT In an inter-disciplinary age to study and write down about a subject that sprawls over several decades and fields is a challenging task. One needs to put forward an argument that is relevant to readers who otherwise may be unaware or indifferent to it. Shakespeare is a subject which has been extensively revisited by artists, critics and scholars around the world. Reshaping of Shakespeare's work from time to time across different disciplines has reshaped our understanding of it repeatedly. Artists borrowed essence of Shakespeare's kaleidoscopic work and redesigned it into resonant patterns, thus leaving behind myriad manifestations to select from. Collaboration ranges from adaptation to appropriation in varying degrees at times difficult to categorize. Along with adaptation into wholly verbal medium (e.g., translations) the practice of indigenization through performing arts has played a great role in amplifying the reach of plays. The theatre and cinema are two medium which has extensively contributed in this cross-cultural exchange over the ages. Indian cinema in its initial years recorded the plays staged by Parsi theatre companies. Theatre being a spectacle has always tempted filmmakers and drew them closer. The researcher in this paper has attempted to delve deeper into the relationship between Shakespeare, Indian theatre and Hindi Cinema. Keywords: Evolution, Hindi Cinema, Indian Floorboards, Relation, Shakespeare I.INTRODUCTION The word Shakespeare refers to the renowned actor, dramatist and the poet William Shakespeare. -

1. How Many West Flowing Rivers Are There in Kerala?

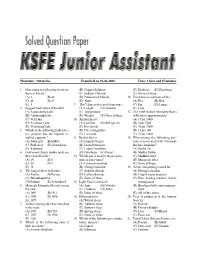

Maximum : 100 marks Exam held on 29-06-2002 Time: 1 hour and 15 minutes 1. How many west flowing rivers are (B) Copper Sulphate (C) Diabetes (D) Diarrhoea there in Kerala? (C) Sodium Chloride (E) None of these (A) 3 (B) 40 (D) Potassium Chloride 16. Trachoma is a disease of the: (C) 41 (D) 21 (E) Alum (A) Eye (B) Skin. (E) 5 9. The Celsius scale is used to measure: (C) Ear (D) Lungs 2. Biggest back water of Kerala? (A) Length (B) Velocity (E) Liver (A) Sastamkotta Lake (C) Temperature 17. The IMR (Infant Mortality Rate) (B) Ashtamudi Lake (D) Weight (E) None of these of Kerala is approximately: (C) Veli Lake 10. Ammonia is a : (A) 13 per 1000 (D) Paravoor Lake (A) Fertilizer (B) Refrigerant (B) 3 per 7000 (E) Vembanad Lake (C) Insecticide (C) 36 per 7000 3. Which of the following hydroelec- (D) Fire extinguisher (D) 13 per 100 tric projects has the highest in- (E) Larvicide (E) 31 per 1000 stalled capacity ? 11. Rocket fuel is : 18. Who among the following per- (A) Sabarigiri (B) Idukki (A) Liquid Oxygen sons is associated with Narmada (C) Pallivasal (D) Edamalayar (B) Liquid Nitrogen Bachao Andolan? (E) Kuttiyadi (C) Liquid Ammonia (A) Shoba De 4. How many Rajya Sabha seats are (D) Petroleum (E) Diesel (B) Medha Patkar there from Kerala ? 12. Which gas is used in the prepara- (C) Madhuri Dixit (A) 14 (B) 5 tion of soda water? (D) Margerret Alva (C) 20 (D) 9 (A) Carbon monoxide (E) None of these (E) 11 (B) Nitrogen dioxide 19. -

Rajinder Singh Bedi (Bio for Centennial Celebrations)

© Nischint Bhatnagar Rajinder Singh Bedi (Bio for Centennial celebrations) Born September 01, 1915 at Lahore Cantonment, Sadar Bazaar; Died November 11, 1984 in Bombay. His father, S. Hira Singh Bedi was a Postmaster. He was very fond of Urdu and Farsi. His Mother Smt. Sewa Dei was from a Hindu family and very knowledgeable of Sikh and Hindu religion, the stories of the Puranas and also of Muslim lore. She was a wonderful painter and had covered the walls of the house with scenes from the Mahabharata. The house had a mixed culture of Sikhism and Hinduism and father took part in Muslim festivals enthusiastically. Rajinder’s imaginative skills were developed under their fond care, storytelling and father’s witticisms. He matriculated from the S.B.B.S. Khalsa High School, Lahore and joined the DAV College, Lahore. He passed his Intermediate but could not go for BA studies. Mother had died March 28, 1933 of tuberculosis and father wanted him to marry so that there may be a caregiver in the family. He left his studies and joined the postal service as a clerk in 1933. He got married in 1934. His wife’s maiden name was Soman and married name Satwant Kaur. His first son, Prem, was born in 1935. Father who was then working as Postmaster in Toba Tek Singh came to Lahore to celebrate the arrival of a grandson but died there on August 31, 1935. The whole burden for fending for his family, his two brothers and sister fell on him and Satwant. The son Prem also passed away in 1936.