Becoming a Clubber: Transitions, Identities and Lifestyles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scarica Qui Il Numero Del Journal in Formato

DIGICULT Digital Art, Design & Culture Fondatore e Direttore: Marco Mancuso Comitato consultivo: Marco Mancuso, Lucrezia Cippitelli, Claudia D'Alonzo Editore: Associazione Culturale Digicult Largo Murani 4, 20133 Milan (Italy) http://www.digicult.it Testata Editoriale registrata presso il Tribunale di Milano, numero N°240 of 10/04/06. ISSN Code: 2037-2256 Licenze: Creative Commons Attribuzione-NonCommerciale-NoDerivati - Creative Commons 2.5 Italy (CC BY-NC-ND 2.5) Stampato e distribuito tramite Peecho Sviluppo ePub e Pdf: Loretta Borrelli Cover design: Eva Scaini INDICE Lucrezia Cippitelli Newmediafix. Edoardo Navas E La Net-information ............................................. 3 Marco Mancuso Pipslab, Audience Is The Artist ................................................................................. 13 Bertram Niessen Vidauxs, Netlabel Per Vedere E Ascoltare .............................................................. 21 Domenico Sciajno Piombino Experimenta ............................................................................................. 24 Alex Dandi House Generation, Il Ritorno Di Jack ...................................................................... 28 Teresa De Feo Le Sintesi Sonore Di Mass .......................................................................................... 31 Simone Bertuzzi Francisco Lopez: Blind Listening ............................................................................. 34 Beatrice Ferrario Computer Sicuro, Ma Per Chi? ................................................................................ -

E Guide the Travel Guide with Its Own Website

Londonwww.elondon.dk.com e guide the travel guide with its own website always up-to-date d what’s happening now London e guide In style • In the know • Online www.elondon.dk.com Produced by Blue Island Publishing Contributors Jonathan Cox, Michael Ellis, Andrew Humphreys, Lisa Ritchie Photographer Max Alexander Reproduced in Singapore by Colourscan Printed and bound in Singapore by Tien Wah Press First published in Great Britain in 2005 by Dorling Kindersley Limited 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL Reprinted with revisions 2006 Copyright © 2005, 2006 Dorling Kindersley Limited, London A Penguin Company All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. A CIP catalogue record is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 4053 1401 X ISBN 978 1 40531 401 5 The information in this e>>guide is checked annually. This guide is supported by a dedicated website which provides the very latest information for visitors to London; please see pages 6–7 for the web address and password. Some information, however, is liable to change, and the publishers cannot accept responsibility for any consequences arising from the use of this book, nor for any material on third party websites, and cannot guarantee that any website address in this book will be a suitable source of travel information. We value the views and suggestions of our readers very highly. Please write to: Publisher, DK Eyewitness Travel Guides, Dorling Kindersley, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, Great Britain. -

Felix Issue 1103, 1998

19 If Issue October 1122 1998 KEEP THE CAT FREE EST 1949 The Students' Newspaper at Imperial College Death Knell for the NUS? MIST and Imperial College Stu• technically it is still a by Ed Sexton prices, and sometimes save an awful lot of money". dents' Unions are to hold a con• member. The decision improve on them. I le also David I lellard, while still insisting that U ference on surviving outside the to disaffiliate this academic year was claimed that Northern Services offers Ihe conference was a forum for exchang• NUS later this month. It is thought that made some months ago but, accodring "more flexibility", as universities can use ing ideas, was more forceful in his criti• the event will be attended by Union offi• to Sabih Behzad, the formal announce• other service providers as well (a scheme cism of the NUS. "UMIST leaving has got cers from many of Britain's top universi• ment will not be made until 4 November. prohibited to NUS members). "One of people thinking" he commented; "there ties. The NUS has asked UMIST to hold a uni• the advantages is it I Northern Services] is a growing discontent with the service The conference will take place on 30 versity-wide referendum on the issue is quite small" explained Mr Bibby. I le Ihey [the NUS] arc providing". Dave Hel• October at UMIST, and has been unoffi• before disaffiliating, which would be sim• denied he was going to the conference lard explained that his role at the con• cially titled 'CHESA: The Way of the ilar to the procedure followed when simply to promote Northern Services. -

Music Video Auteurs: the Directors Label Dvds

i Music Video Auteurs: The Directors Label DVDs and the Music Videos of Chris Cunningham, Michel Gondry and Spike Jonze. by Tristan Fidler Bachelor of Arts (With First Class Honours), UWA ’04. This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Western Australia. English, Communication and Cultural Studies. 2008 ii MUSIC VIDEO AUTEURS ABSTRACT Music video is an intriguing genre of television due to the fact that music drives the images and ideas found in numerous and varied examples of the form. Pre-recorded pieces of pop music are visually written upon in a palimpsest manner, resulting in an immediate and entertaining synchronisation of sound and vision. Ever since the popularity of MTV in the early 1980s, music video has been a persistent fixture in academic discussion, most notably in the work of writers like E. Ann Kaplan, Simon Frith and Andrew Goodwin. What has been of major interest to such cultural scholars is the fact that music video was designed as a promotional tool in their inception, supporting album sales and increasing the stardom of the featured recording artists. Authorship in music video studies has been traditionally kept to the representation of music stars, how they incorporate post-modern references and touch upon wider cultural themes (the Marilyn Monroe pastiche for the Madonna video, Material Girl (1985) for instance). What has not been greatly discussed is the contribution of music video directors, and the reason for that is the target audience for music videos are teenagers, who respond more to the presence of the singer or the band than the unknown figure of the director, a view that is also adhered to by music television channels like MTV. -

Banksy. Urban Art in a Material World

Ulrich Blanché BANKSY Ulrich Blanché Banksy Urban Art in a Material World Translated from German by Rebekah Jonas and Ulrich Blanché Tectum Ulrich Blanché Banksy. Urban Art in a Material World Translated by Rebekah Jonas and Ulrich Blanché Proofread by Rebekah Jonas Tectum Verlag Marburg, 2016 ISBN 978-3-8288-6357-6 (Dieser Titel ist zugleich als gedrucktes Buch unter der ISBN 978-3-8288-3541-2 im Tectum Verlag erschienen.) Umschlagabbildung: Food Art made in 2008 by Prudence Emma Staite. Reprinted by kind permission of Nestlé and Prudence Emma Staite. Besuchen Sie uns im Internet www.tectum-verlag.de www.facebook.com/tectum.verlag Bibliografische Informationen der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Angaben sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. Table of Content 1) Introduction 11 a) How Does Banksy Depict Consumerism? 11 b) How is the Term Consumer Culture Used in this Study? 15 c) Sources 17 2) Terms and Definitions 19 a) Consumerism and Consumption 19 i) The Term Consumption 19 ii) The Concept of Consumerism 20 b) Cultural Critique, Critique of Authority and Environmental Criticism 23 c) Consumer Society 23 i) Narrowing Down »Consumer Society« 24 ii) Emergence of Consumer Societies 25 d) Consumption and Religion 28 e) Consumption in Art History 31 i) Marcel Duchamp 32 ii) Andy Warhol 35 iii) Jeff Koons 39 f) Graffiti, Street Art, and Urban Art 43 i) Graffiti 43 ii) The Term Street Art 44 iii) Definition -

Daft Punk's Discovery

First published by Velocity Press 2021 velocitypress.uk Copyright © Ben Cardew 2021 Cover design Augusto Calvo Losada Typesetting Paul Baillie-Lane pblpublishing.co.uk Ben Cardew has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identi ed as the author of this work All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission from the publisher ISBN: 9781913231118 1: SOMETHING ABOUT US HOW DAFT PUNK ARRIVED AT DISCOVERY “It ain’t what they call you, it’s what you answer to.” WC Fields Like all the best adventures, our journey into Discovery should begin from simple roots. So let’s start with a band’s name. It is one of the splendid ironies of the music business, where brand and image are all important, that changing a band’s name is such a di¤cult process. According to a 1993 interview with Select magazine,1 grunge-light indie act e Lemonheads needed a legal document to mark their transition from “Lemonheads” to “e Lemonheads”, a change so minute it gets lost in punctuation. At the same time, the actual meaning of a band’s name – however outlandish – tends to be forgotten. No one considers how ridiculous the words “Arctic Monkeys” are when put together; we immediately think of the internationally famous, festival-topping band, their name free from other, more literal, associations. Similarly, Daft Punk are just Daft Punk. You may know how their name came about – from a Melody Maker review of their brief Daft Punk precursor band, Darlin’, that dismissed them as “daft punky thrash” – but you probably don’t think too much about it. -

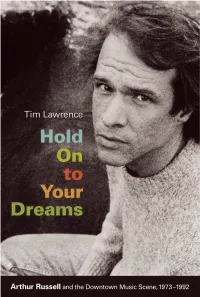

Tim Lawrence

Hold On to Your Dreams Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, 1973–1992 Tim Lawrence Hold On to Your Dreams is the first biography of the musician and composer Arthur Russell, one of the most important but least known contributors to New York’s downtown music scene during the 1970s and 1980s. With the exception of a few dance recordings, including “Is It All Over My Face?” and “Go Bang! #5,” Russell’s pioneering music was largely forgotten until 2004, when the posthumous release of two albums brought new attention to the artist. This revival of interest gained momentum with the issue of additional albums and the documentary film Wild Combination. Based on interviews with more than seventy of his collaborators, family members, and friends, Hold On to Your Dreams provides vital new information about this singular, eccentric musician and his role in the boundary-breaking downtown music scene. Tim Lawrence traces Russell’s odyssey from his hometown of Oskaloosa, Iowa, to countercultural San Francisco, and eventually to New York, where he lived from 1973 until his death from AIDS-related complications in 1992. Resisting definition while dreaming of commercial success, Russell wrote and performed new wave and disco as well as quirky rock, twisted folk, voice-cello dub, and hip-hop-inflected pop. “He was way ahead of other people in understanding that the walls between concert music and popular music and avant-garde music were illusory,” comments the composer Philip Glass. “He lived in a world in which those walls weren’t there.” Lawrence follows Russell across musical genres and through such vital downtown music spaces as the Kitchen, the Loft, the Gallery, the Paradise Garage, and the Experimental Intermedia Foundation. -

Massive Attack's First Album Was a “Record of Rebellion, Its Chin Smugly

Massive Attack’s first album was a “record of rebellion, its chin smugly forward; its noncommittal cross-racial dynamic a thumbed nose at the British popular culture that still retained the trace of racial and social cultural divisions.” Wheaton, R.J. (2011) DUMMY, London: Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 219. Why is Blue Lines such a culturally important record? There is an irony not to be overlooked in the fact that whilst Blue Lines was celebrated as the dance album of the 90s its creators exploded all boundaries and stylistic paradigms attached to the very genre of dance music. As Grant Marshall, aka Daddy G, explained in an interview with NME: “we’re outside of categories and that’s because where we come from.”1 The sensory beauty of this record relates to the authenticity in which Massive Attack reflect the cultural, social, racial, economic, political and geographic circumstances of their own backgrounds. As I will outline, this masterpiece is connected to its geographic location; its sonic texture and expressions not to be understood without knowing the relevant historic context of urban life in the 80s and early 90s of England; Thatcher’s neoliberalism, emerging social and political struggles as well as the impact of punk and hip-hop and their associated rebellious attitudes. 1 Kessler, 1998, THIS is THE STORY OF THE BLUES, NME, London: IPC Specialist Group, Issue April 11th, p. 33 1 I Benno Schlachter 2013 © Blue Lines, amongst other things, is a sonic answer to the history of its birthplace, the city of Bristol. As one of the biggest British perpetrators and profiteers of the slave trade consequently inherited a racist atmosphere to a city with a huge African-Caribbean population. -

“Surely People Who Go Clubbing Don't Read”: Dispatches from The

“Surely people who go clubbing don’t read”: Dispatches from the Dancefloor and Clubland in Print Simon A. Morrison University of Chester [email protected] Abstract In the context of the UK dance club scene during the 1990s, this article redresses a presumption that “people who go clubbing don’t read”. It will thereby test a proposed lacuna in original journalist voices in related print media. The examination is based on key UK publications that focus on the musical tropes and modes of the dancefloor, and on responses from a selection of authors and editors involved in British club culture during this era. The style of this article is itself a methodology that deploys ‘gonzo’ strategies typical of earlier New Journalism, in reaching for a new approach to academicism. In seeking to discover whether the idea that clubbers do not read is due to inauthentic media re/presentations of their experience on the dancefloor, or with specific subcultural discourses, the article concludes that the authenticity of club cultural re/presentation may well be found in fictional responses. Keywords: music journalism, gonzo journalism, chemical generation literature, electronic dance music culture (EDMC). Welcome to the disco-text This article will interrogate the claim made in 2000 by writer and editor Sarah Champion regarding a lacuna in auteur journalist voices, in relation to club culture media products. Her broader reports about a perceived unwillingness amongst clubbers to read at all — “surely clubbers don’t read” — form part of Steve Redhead’s collection Repetitive Beat Generation (2000: 18). Within this title, Champion further asserts about the genre- specific media of this subcultural scene that, “There should have been some kind of ‘Gonzo’ journalism to capture the spirit but there wasn’t”. -

Discorder April 200 1 That Fluffy Tailed Magazine from Citr 101.9 Fm

DISCORDER APRIL 200 1 THAT FLUFFY TAILED MAGAZINE FROM CITR 101.9 FM WEIGHTS & MEASURES • ANION TOBIN • FROG EYES • KIA KADIRI SOLARBABY • LADYTRON • CANNED HAMM DIARY i— t^n\jr g MO INJ -IT TOUR DE with special guests I Tickets Available At I I ucHotmaaror | At Richards on Richards j (604) 280-4444 f 1036 Richards St. AND ONE BASSIX Vancouver, BC IIMM* h*£ 217 W. Hastings & Landscape Body Machine (604) 689 - 7734 Doors at 8 pm *MP Jr? ?f J ROC CATCH'EM WFJ ©THE COMMODORE SATURDAY APRIL 28TH, NOISE CONSPIRACY R0CK1T FROM THE CRYJPJL JHE (I NTERNATIONAl) NOISE CONSPIRACY ^GROUP SOUNDS" "SURVIVAL SICKNESS" RES QVAGRANT > WATER STREET VANCOUVER CANADA Events at a glance: heavily sedated: Barbara Andersen frffi#lffffi in training: Lyndsay Sung kia kadiri by hancunt p. 12 ad rep: DJ Z-TRIP @ CROSSFADE FRIDAYS solarbaby by spike p. 13 Maren Hancock art directrix: frog eyes by jay aouillara p. 14 Lori Kiessling ladytron by Christine gfroerer p. 15 assistant art director: amon tobin by luke meat and robert robot p. 16 Matt Searcey THURSDAY APRIL 19 weights and measures by lia kiessling p. 17 producfion mananger: Christa Min MARQUES WYATT canned hamm tour diary by little hamm p. 19 photo editor: Ann Goncalves real live action editor: STRICTLY RHYTHM, KING STREET i... _ Steve DiPasquale •fe AmaHnrl* "Hn.iR« Music" On YOSHITOSHI, layout: interview hell p. 5 Russ "Switch" Davidson, Farah Dharshi, Lori, Matt Searcy, Tara 7" p. 6 Westover radio free press p. 7 photography and illustrations: SATURDAY APRIL 21 Hoi strut and fret p. -

Cultato? Hai Una Tua Filosofia Di Vita? R

mensile di intelligente n.7 ottobre 2004 intrattenimento 2 EDITORIALE bazar 10 2004 [email protected] MAra Codalli Eugenia ROmanelli Vera RIsi Direttore arTistico Direttore responsabile viceDirettore bazar 10 2004 laboratori studenti la sapienza 3 [email protected] , NERISCHIO VALE LA PENA? MORTALE Ogni gioco ha le sue regole? Non tutti. Certi giochi superano ogni limite. Sport talmente spericolati ed eccitanti da creare dipendenza. Sfide all’estremo che a volte mettono a rischio anche la vita di chi non gioca. Giochi divertenti da morire? Si, perchè a volte si muore davvero. Bungee Jumping: volare si può Il bungee jumping consiste nell’ effettuare un salto nel vuoto da ponti, gru, elicotteri o mongolfiere legati a un elastico. La forma più estrema di questo sport è il BASE JUMPING. Ci si getta da edifici, antenne, ponti e dirupi, ma senza l’elastico a fermare il volo. In questo caso il jumper apre il paracadute solo all’ultimo momento quando il margine per non sfracellarsi è di appena due o tre secondi. Una tremenda scarica di adrenalina, un gesto di piena follia, che somma al rischio di lasciarci la pelle quello di finire in galera. La sfida dentro la sfida è, infatti, quella di lanciarsi da luoghi speciali, simbolici, pericolosissimi o vietati, come la Statua della libertà o la Torre Eiffel. Eppure basta poco, una raffica di vento, un errore nel tempo di apertura del paracadute e l’avventura si conclude in tragedia. I “jumpers” hanno tra i venti ei trent’anni d’ età. In maggioranza maschi, non mancano ultracinquantenni e giovanissimi. Per i campioni del brivido non conta solo l’espressione liberatoria dell’energia fisica, ma piuttosto la sua gestione e il suo allenamento. -

O/191/02 25Kb

TRADE MARKS ACT 1994 IN THE MATTER OF APPLICATION No. 2042246A IN THE NAME OF IPC MEDIA LIMITED AND IN THE MATTER OF OPPOSITION THERETO UNDER No. 48931 BY LOADED RECORDS LIMITED AND IN THE MATTER OF AN APPEAL TO THE APPOINTED PERSON BY THE APPLICANTS AGAINST THE DECISION OF MR M. FOLEY DATED 14 AUGUST 2001 ______________________ DECISION ______________________ Background 1. Since April 1994, IPC Media Limited (“the applicants”) have produced a monthly magazine called LOADED primarily aimed at a male readership aged between 20 – 35 years old. I believe the title might popularly be described as a “lads” magazine. 2. The success of the magazine caused the applicants to turn their minds to merchandising and by an application dated 23 October 1995 they applied under number 2042246 to register the trade mark LOADED for a variety of goods and services in Classes 9, 35, 41 and 42. 3. On 27 August 1998, Loaded Records Limited (“the opponents”) filed notice of opposition against the application. Although a number of grounds were stated, the opponents came to rely on one ground only: that under section 5(4)(a) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (“the TMA”) the applicants’ mark was liable to be prevented in use in the UK by the law of passing off. The opposition did not concern the services application in Classes 35, 41 and 42, which was subsequently divided off under number 2042246B and in the absence of opposition proceeded to registration. Following division, the opposed application in Class 9 was renumbered 2042246A. 4. The goods in Application No.