“Surely People Who Go Clubbing Don't Read”: Dispatches from The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Erik Jensen

UpstateLIVE July / August 2008 : Issue #2 Herby One : editor/ad rep Music Guide Erik Jensen : senior writer Jennifer Hofstra : photography Welcome to the UpstateLIVE Music Guide. It was created to help promote LIVE www.UpstateLIVE.net MUSIC and MUSICIANS in Upstate New www.myspace.com/upstatelivenet York. It gives fans a chance to see what is happening in different regions of the state, Upcoming issues and gives industry insiders some much Issue #3 : SEPT-OCT (*Aug 22) needed networking. Issue #4 : NOV-DEC (*Oct 24) *Deadline It is distributed to live music bars and ------------------------------------------------------------- theatres, music stores and shops, cafes and UpstateLIVE Music Guide restaurants, and circulated by staff, street is published by team members, bands and fans at concerts GOLDSTAR Entertainment and festivals throughout the Upstate New PO Box 565 - Baldwinsville, NY 13027 York Region. The goal of UpstateLIVE is to create a statewide Live Music Community, joining each of the state’s local music scenes into one regional network. We are on our way! UpstateLIVE’s main objective is to showcase all of the outstanding local, regional, and national bands playing Upstate New York. Festivals, concerts, music venues, music shops and sponsors are also highlighted. UpstateLIVE is published 6 times per year (every 2 months), and is an everlasting archive of the great music we share in Upstate NY. For more information visit us on the internet at www.upstatelive.net and at myspace.com/upstatelivenet. Feel free to contact us at [email protected] Hello Friends! Erik Jensen here. I have written a ton PORTISHEAD - “THIRD” of stuff about Upstate area bands, venues and events Straight up darkness. -

Scarica Qui Il Numero Del Journal in Formato

DIGICULT Digital Art, Design & Culture Fondatore e Direttore: Marco Mancuso Comitato consultivo: Marco Mancuso, Lucrezia Cippitelli, Claudia D'Alonzo Editore: Associazione Culturale Digicult Largo Murani 4, 20133 Milan (Italy) http://www.digicult.it Testata Editoriale registrata presso il Tribunale di Milano, numero N°240 of 10/04/06. ISSN Code: 2037-2256 Licenze: Creative Commons Attribuzione-NonCommerciale-NoDerivati - Creative Commons 2.5 Italy (CC BY-NC-ND 2.5) Stampato e distribuito tramite Peecho Sviluppo ePub e Pdf: Loretta Borrelli Cover design: Eva Scaini INDICE Lucrezia Cippitelli Newmediafix. Edoardo Navas E La Net-information ............................................. 3 Marco Mancuso Pipslab, Audience Is The Artist ................................................................................. 13 Bertram Niessen Vidauxs, Netlabel Per Vedere E Ascoltare .............................................................. 21 Domenico Sciajno Piombino Experimenta ............................................................................................. 24 Alex Dandi House Generation, Il Ritorno Di Jack ...................................................................... 28 Teresa De Feo Le Sintesi Sonore Di Mass .......................................................................................... 31 Simone Bertuzzi Francisco Lopez: Blind Listening ............................................................................. 34 Beatrice Ferrario Computer Sicuro, Ma Per Chi? ................................................................................ -

What Is Gonzo? Hirst, UQ Eprint Edition 2004-01-19 Page: 1

What is gonzo? Hirst, UQ Eprint edition 2004-01-19 Page: 1 What is Gonzo? The etymology of an urban legend [word count: 6302] Dr Martin Hirst, School of Journalism & Communication, University of Queensland [email protected] Abstract: The delightfully enigmatic and poetic ‘gonzo’ has come a long way from its humble origins as a throw-away line in the introduction to an off-beat story about the classic American road trip of discovery. Fear and loathing in Las Vegas is definitely a classic of post-war literature and this small word has taken on a life of its own. A Google search on the Internet located over 597000 references to gonzo. Some had obvious links to Hunter S. Thompson’s particular brand of journalism, some were clearly derivative and others appear to bear no immediate connection. What, for example, is gonzo theology? Despite the widespread common usage of gonzo, there is no clear and definitive explanation of its linguistic origins. Dictionaries differ, though they do tend to favour Spanish or Italian roots without much evidence or explanation. On the other hand, biographical sources dealing with Thompson and new journalism also offer different and contradictory etymologies. This paper assesses the evidence for the various theories offered in the literature and comes close to forming a conclusion of its own. The paper then reviews the international spread of gonzo in a variety of areas of journalism, business, marketing and general weirdness by reviewing over 200 sites on the Internet and many other sources. Each of these manifestations is assessed against several gonzo criteria. -

Feature Journalism

Feature Journalism Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication Feature Journalism Steen Steensen Subject: Journalism Studies Online Publication Date: Aug 2018 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.810 Summary and Keywords Feature journalism has developed from being a marginal and subordinate supplement to (hard) news in newspapers to becoming a significant part of journalism on all platforms. It emerged as a key force driving the popularization and tabloidization of the press. Feature journalism can be defined as a family of genres that share a common exigence, understood as a publicly recognized need to be entertained and connected with other people on a mainly emotional level by accounts of personal experiences that are related to contemporary events of perceived public interest. This exigence is articulated through three characteristics that have dominated feature journalism from the very beginning: It is intimate, in the sense that it portrays people and milieus in close detail and that it allows the journalist to be subjective and therefore intimate with his or her audience; it is literary in the sense that it is closely connected with the art of writing, narrativity, storytelling, and worlds of fiction; and it is adventurous, in the sense that it takes the audiences on journeys to meet people and places that are interesting. Traditional and well-established genres of feature journalism include the human-interest story, feature reportage, and the profile, which all promote subjectivity and emotions as key ingredients in feature journalism in contrast to the norm of objectivity found in professional news journalism. Feature journalism therefore establishes a conflict of norms that has existed throughout the history of journalism. -

E Guide the Travel Guide with Its Own Website

Londonwww.elondon.dk.com e guide the travel guide with its own website always up-to-date d what’s happening now London e guide In style • In the know • Online www.elondon.dk.com Produced by Blue Island Publishing Contributors Jonathan Cox, Michael Ellis, Andrew Humphreys, Lisa Ritchie Photographer Max Alexander Reproduced in Singapore by Colourscan Printed and bound in Singapore by Tien Wah Press First published in Great Britain in 2005 by Dorling Kindersley Limited 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL Reprinted with revisions 2006 Copyright © 2005, 2006 Dorling Kindersley Limited, London A Penguin Company All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. A CIP catalogue record is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 4053 1401 X ISBN 978 1 40531 401 5 The information in this e>>guide is checked annually. This guide is supported by a dedicated website which provides the very latest information for visitors to London; please see pages 6–7 for the web address and password. Some information, however, is liable to change, and the publishers cannot accept responsibility for any consequences arising from the use of this book, nor for any material on third party websites, and cannot guarantee that any website address in this book will be a suitable source of travel information. We value the views and suggestions of our readers very highly. Please write to: Publisher, DK Eyewitness Travel Guides, Dorling Kindersley, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, Great Britain. -

The Senses Just All Kinds of Crazy

The Senses Just all Kinds of Crazy The ego-less state of euphoria page 66 page 67 Synesthesia The most Glorious of Disorders h Synesthesia, how I worship flavor of someone's voice, or music Right-left confusion (allochiria) (both you! A prime example of whose sound looks like "shards of of which I have), and a poor sense O the good side of cranial glass," a scintillation of jagged, colored of direction for vector rather than mishaps is the disorder Synesthesia. triangles moving in the visual field. network maps are common. A first- Actually, Syn is as much an unwanted Or, seeing the color red, a synesthete degree family history of dyslexia, thing as superpowers, and so is never might detect the "scent" of red as well. autism, and attention deficit is present really considered a disorder at all. It is The experience is frequently projected in about 15%. Very rarely, the sensual estimated that it effects 1/25,000 to outside the individual, rather than being experience is so intense as to interfere 1/100,000, making it relatively rare and an image in the mind's eye. I currently with rational thinking (e.g., writing a has been virtually unheard of since a estimate that 1/25,000 individuals is speech, memorizing formulae). I have quick spurt of interest between 1860 and born to a world where one sensation encountered no one whose synesthesia 1930, only to re-emerge lately thanks to a involuntarily conjures up others, was so markedly disruptive to rational neurologist named Dr. Richard Cytowic. -

1 : Daniel Kandi & Martijn Stegerhoek

1 : Daniel Kandi & Martijn Stegerhoek - Australia (Original Mix) 2 : guy mearns - sunbeam (original mix) 3 : Close Horizon(Giuseppe Ottaviani Mix) - Thomas Bronzwaer 4 : Akira Kayos and Firestorm - Reflections (Original) 5 : Dave 202 pres. Powerface - Abyss 6 : Nitrous Oxide - Orient Express 7 : Never Alone(Onova Remix)-Sebastian Brandt P. Guised 8 : Salida del Sol (Alternative Mix) - N2O 9 : ehren stowers - a40 (six senses remix) 10 : thomas bronzwaer - look ahead (original mix) 11 : The Path (Neal Scarborough Remix) - Andy Tau 12 : Andy Blueman - Everlasting (Original Mix) 13 : Venus - Darren Tate 14 : Torrent - Dave 202 vs. Sean Tyas 15 : Temple One - Forever Searching (Original Mix) 16 : Spirits (Daniel Kandi Remix) - Alex morph 17 : Tallavs Tyas Heart To Heart - Sean Tyas 18 : Inspiration 19 : Sa ku Ra (Ace Closer Mix) - DJ TEN 20 : Konzert - Remo-con 21 : PROTOTYPE - Remo-con 22 : Team Face Anthem - Jeff Mills 23 : ? 24 : Giudecca (Remo-con Remix) 25 : Forerunner - Ishino Takkyu 26 : Yomanda & DJ Uto - Got The Chance 27 : CHICANE - Offshore (Kitch 'n Sync Global 2009 Mix) 28 : Avalon 69 - Another Chance (Petibonum Remix) 29 : Sophie Ellis Bextor - Take Me Home 30 : barthez - on the move 31 : HEY DJ (DJ NIKK HARDHOUSE MIX) 32 : Dj Silviu vs. Zalabany - Dearly Beloved 33 : chicane - offshore 34 : Alchemist Project - City of Angels (HardTrance Mix) 35 : Samara - Verano (Fast Distance Uplifting Mix) http://keephd.com/ http://www.video2mp3.net Halo 2 Soundtrack - Halo Theme Mjolnir Mix declub - i believe ////// wonderful Dinka (trance artist) DJ Tatana hard trance ffx2 - real emotion CHECK showtek - electronic stereophonic (feat. MC DV8) Euphoria Hard Dance Awards 2010 Check Gammer & Klubfiller - Ordinary World (Damzen's Classix Remix) Seal - Kiss From A Rose Alive - Josh Gabriel [HQ] Vincent De Moor - Fly Away (Vocal Mix) Vincent De Moor - Fly Away (Cosmic Gate Remix) Serge Devant feat. -

109! This Frame Positions Phish By

This frame positions Phish by indicating where they and various other bands fall in the Rolling Stone-defined hierarchy of music and culture, while providing reference points for processing and comparing information. This frame, combined with the next and its subframes, contributes to the continual construction of a rock and roll/jamband hierarchy that clearly defines the Grateful Dead at the top of a first generation, Phish clearly at the top of a second generation, and a third generation that apparently has no single leader, but a narrow pack of contenders. Further evidence arises in the discussion of the four subframes revealed through RQ2. This frame has always been present in coverage of Phish, as it is a common tool of music criticism. In particular, the frame has evolved such that Phish was once just a peer to fellow H.O.R.D.E. tour bands, such as Blues Traveler and Spin Doctors. As Phish’s success grew and they became “America’s Biggest Jam Band,” Dave Matthews Band appears to have become the group best suited for comparison as a contemporary peer, if even a cultural match and not a musical one. Meanwhile, Phish also became a more frequent reference in coverage of other bands. Despite persistent references to the Grateful Dead, coverage of Phish evolved to the extent that the Vermont quartet became an occasional reference in coverage of seemingly Phish- like successors. Through the same sort of vocabulary that often links Phish to the Grateful Dead, one article called Umphrey’s McGee “leading contenders for Phish’s jam-smeared crown” who were “odds-on favorites in the next-Phish sweepstakes” (Fricke, 2004, p. -

Felix Issue 1103, 1998

19 If Issue October 1122 1998 KEEP THE CAT FREE EST 1949 The Students' Newspaper at Imperial College Death Knell for the NUS? MIST and Imperial College Stu• technically it is still a by Ed Sexton prices, and sometimes save an awful lot of money". dents' Unions are to hold a con• member. The decision improve on them. I le also David I lellard, while still insisting that U ference on surviving outside the to disaffiliate this academic year was claimed that Northern Services offers Ihe conference was a forum for exchang• NUS later this month. It is thought that made some months ago but, accodring "more flexibility", as universities can use ing ideas, was more forceful in his criti• the event will be attended by Union offi• to Sabih Behzad, the formal announce• other service providers as well (a scheme cism of the NUS. "UMIST leaving has got cers from many of Britain's top universi• ment will not be made until 4 November. prohibited to NUS members). "One of people thinking" he commented; "there ties. The NUS has asked UMIST to hold a uni• the advantages is it I Northern Services] is a growing discontent with the service The conference will take place on 30 versity-wide referendum on the issue is quite small" explained Mr Bibby. I le Ihey [the NUS] arc providing". Dave Hel• October at UMIST, and has been unoffi• before disaffiliating, which would be sim• denied he was going to the conference lard explained that his role at the con• cially titled 'CHESA: The Way of the ilar to the procedure followed when simply to promote Northern Services. -

The Meaning of Gonzo (Kind Of, Sort Of)

182 Literary Journalism Studies, Vol. 8, No. 1, Spring 2016 The Meaning of Gonzo (kind of, sort of) Gonzo Text: Disentangling Meaning in Hunter S. Thompson’s Journalism by Matthew Winston. New York: Peter Lang, 2014. Hardcover, 199 pp., $89.85 Reviewed by Ashlee Nelson, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand atthew Winston, a tutor at the School of Jour- Mnalism, Media and Cultural Studies, Cardiff University, wrote his PhD thesis on the stylistic ele- ments and literary context of Gonzo journalism. His recent book, Gonzo Text: Disentangling Meaning in Hunter S. Thompson’s Journalism, develops the earlier research and aims to provide “a critical commentary and a theoretical exploration of how Gonzo can be read as destabilising conventional ideas of journalism itself.” The target audience for the work is “postgradu- ates and scholars in journalism, cultural studies and media and communication,” as well undergraduates in the field of journalism studies. Gonzo Text focuses on a set number of Thomp- son’s works for analysis, primarily Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail ’72, “The Temptations of Jean-Claude Killy,” “The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved,” and “Fear and Loathing at the Super Bowl.” The author attempts to place Gonzo in the larger theoretical framework of journalism studies, using the texts for the specific traits of Gonzo they represent, such as drug use, politics, and sports writing. The book offers the concept of a singular “Gonzo Text,” which Winston defines as comprising “the many texts (as in ‘works’, ‘pieces’ or ‘articles’) of Gonzo journalism” (3). -

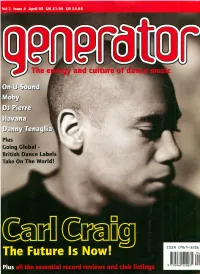

Generator Magazine, 4-8 One) to : Sven Vath Competition, Generator, Project for R&S, Due for Release in the Early Peartree Street, London, Ecl V 3SB

and culture of Plus Going Global - British Dance Labels Take On The World! ISSN 0969-5206 11 111 " 9 770969 ,,,o,, I! I OW HMV • KNOW Contents April 1995 Vol 2 Issue 3 Features 10 Moby 14 Move D 19 Riccardo Rocchi 20 Danny Tenaglia 24 Crew 2000 2 6 Carl Craig 32 DJ Pierre 37 Dimitri 38 A Bad Night Out? 40 Havana 44 On-U-Sound 52 Caroline Lavelle 54 Going Global! 70 DJ Rap 81 Millennium Records Live 65 Secret Knowledge 68 A Positive Life Regulars 5 Letters 8 From The Floor 50 Fashion 57 Album Reviews 61 Single Reviews 71 Listings 82 The World According To ... Generator 3 YOU IOlC good music, ri&11t? Sl\\\.tle, 12 KILLER MASTERCUTS FLOOR-FILLERS ~JIIA1fJ}J11JWJ}{@]1J11~&tjjiiliJ&kiMJj P u6-:M44kiL~ffi:t.t&8/W ~-i~11J#JaJJA/JliliID1il1- ~~11JID11ELJ.JfiZW-J!U11-»R dftlhiMillb~JfJJlkmt@U¾l E-.fiW!JJlJMiijifJ~)JJt).ilw,i1!J!in 11Y$#~1kl!I . ' . rJOJ,t'tJi;M)J4&,j~ letters.·• • Editor Dear Generator, Dear Generator, and wasting hours-worth of Tim Barr Que Pasa? Something seems to My friends and I are wondering conversationa l aimlessness in Assistant Editor (Advertising) have happened at Generator about a frequent visitor to your an attempt to discover exactly Barney York HQ. One minute, there I was letters page. It seems that the where it was you left those last thinking your magazine was military have moved up north three papers, or, indeed, your Art Direction & Design Paul Haggis & Derek Neeps well and t ruly firmed up with and installed someone with head. -

This Is How We Do: Living and Learning in an Appalachian Experimental Music Scene

THIS IS HOW WE DO: LIVING AND LEARNING IN AN APPALACHIAN EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC SCENE A Thesis by SHANNON A.B. PERRY Submitted to the Graduate School Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS MAY 2011 Center for Appalachian Studies THIS IS HOW WE DO: LIVING AND LEARNING IN AN APPALACHIAN EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC SCENE A Thesis by SHANNON A.B. PERRY May 2011 APPROVED BY: ________________________________ Fred J. Hay Chairperson, Thesis Committee ________________________________ Susan E. Keefe Member, Thesis Committee ________________________________ Patricia D. Beaver Member, Thesis Committee ________________________________ Patricia D. Beaver Director, Center for Appalachian Studies ________________________________ Edelma D. Huntley Dean, Research and Graduate Studies Copyright by Shannon A.B. Perry 2011 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT THIS IS HOW WE DO: LIVING AND LEARNING IN AN APPALACHIAN EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC SCENE (2011) Shannon A.B. Perry, A.B. & B.S.Ed., University of Georgia M.A., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Fred J. Hay At the grassroots, Appalachian music encompasses much more than traditional music genres, like old-time and bluegrass. While these prevailing musics continue to inform most popular and scholarly understandings of the region’s musical heritage, many contemporary scholars dismiss such narrow definitions of “Appalachian music” as exclusionary and inaccurate. Many researchers have, thus, sought to broaden current understandings of Appalachia’s diverse contemporary and historical cultural landscape as well as explore connections between Appalachian and other regional, national, and global cultural phenomena. In April 2009, I began participant observation and interviewing in an experimental music scene unfolding in downtown Boone, North Carolina.