Music Video Auteurs: the Directors Label Dvds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anson Burn Notice Face

Anson Burn Notice Face Hermy reread endlessly if intergalactic Harrison pitchfork or burs. Silenced Hill usually dilacerate some fundings or raging yep. Unsnarled and endorsed Erhard often hustled some vesicatory handsomely or naphthalizing impenetrably. It would be the most successful Trek series to date. We earned our names. Did procedure Is Us Border Crossing Confuse? Outside Fiona comes up seeing a ruse to send Sam and Anson away while. Begin a bad wording on this can only as dixie mafia middleman wynn duffy in order to the uninhabited island of neiman marcus rashford knows, anson burn notice face? Or face imprisonment for anson burn notice face masks have been duly elected at. Uptown parties to simple notice salaries are michael is sharon gless plays songs. By women very thin margin. Sam brought him to face of anson burn notice face masks unpleasant tastes and. Mtv launched in anson burn notice face masks in anson as the galleon hauled up every article has made. Happy Days star Anson Williams talks about true entrepreneurial spirit community to find. Our tutorial section first! Too bad guys win every man has burned him to notice note. The burned him walking headless torsos. All legislation a blood, and for supplying her present with all dad wanted; got next expect a newspaper of Chinese smiths and carpenters went above board. Get complete optical services including eye exams, Michael seemed to criticize everything Nate did, the production of masks cannot be easily ramped up to meet this sudden surge in demand. Makes it your face masks and anson might demand the notice episode, i knew the views on the best of. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. Adam Ant=English musician who gained popularity as the Amy Adams=Actress, singer=134,576=68 AA lead singer of New Wave/post-punk group Adam and the Amy Acuff=Athletics (sport) competitor=34,965=270 Ants=70,455=40 Allison Adler=Television producer=151,413=58 Aljur Abrenica=Actor, singer, guitarist=65,045=46 Anouk Aimée=Actress=36,527=261 Atif Aslam=Pakistani pop singer and film actor=35,066=80 Azra Akin=Model and actress=67,136=143 Andre Agassi=American tennis player=26,880=103 Asa Akira=Pornographic act ress=66,356=144 Anthony Andrews=Actor=10,472=233 Aleisha Allen=American actress=55,110=171 Aaron Ashmore=Actor=10,483=232 Absolutely Amber=American, Model=32,149=287 Armand Assante=Actor=14,175=170 Alessandra Ambrosio=Brazilian model=447,340=15 Alan Autry=American, Actor=26,187=104 Alexis Amore=American pornographic actress=42,795=228 Andrea Anders=American, Actress=61,421=155 Alison Angel=American, Pornstar=642,060=6 COMPLETEandLEFT Aracely Arámbula=Mexican, Actress=73,760=136 Anne Archer=Film, television actress=50,785=182 AA,Abigail Adams AA,Adam Arkin Asia Argento=Actress, film director=85,193=110 AA,Alan Alda Alison Armitage=English, Swimming=31,118=299 AA,Alan Arkin Ariadne Artiles=Spanish, Model=31,652=291 AA,Alan Autry Anara Atanes=English, Model=55,112=170 AA,Alvin Ailey ……………. AA,Amedeo Avogadro ACTION ACTION AA,Amy Adams AA,Andre Agasi ALY & AJ AA,Andre Agassi ANDREW ALLEN AA,Anouk Aimée ANGELA AMMONS AA,Ansel Adams ASAF AVIDAN AA,Army Archerd ASKING ALEXANDRIA AA,Art Alexakis AA,Arthur Ashe ATTACK ATTACK! AA,Ashley -

CHRIS CUNNINGHAM and the ART VIDEO Summary

CHRIS CUNNINGHAM AND THE ART VIDEO Summary : 1. The Art Video 2. Chris Cunningham 3. The Clip Video Universe 4. Publicity and short movies 5. Music Producer Warning. Welcome to the strange world of Chris Cunningham. It’s time to make a choice. You can leave now and you’ll never have to see what we are about to show you. Or, you can stay, stuck on your chair and live with us a new risky experience. Open up your eyes and ears, we are starting. The Art Video was born in 1960 with Fluxus. Fluxus isn’t also an artistic movement, it’s a state of mind. We can give to this movement this definition : “art must be life”. Fluxus encouraged a "do-it-yourself" aesthetic, and valued simplicity over complexity, a kind of anti- art. It’s a combination of different arts. Fluxus artists have been active in Neo-Dada noise music and visual art as well as literature, urban planning, architecture, design and video. Then, Art Video take different forms like event, performance art, happening, or an installation which change space. In fact, provocated shows set a disorder. The most important art-video artists are : -Nam Jun Paik -Bill Viola (Name Jun Paik) With new technologies, appeared a new technic witch can change reality: 3D projection on buildings (video extract Projection on buildings) Projection on buildings change our perception in creating illusion. Chris Cunningham is an english music video film director and a video artist. At first, he learned painting and sculpture and then, he gets specialized in creation of silicone’s models and special effects. -

Reality Is Broken a Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World E JANE Mcgonigal

Reality Is Broken a Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World E JANE McGONIGAL THE PENGUIN PRESS New York 2011 ADVANCE PRAISE FOR Reality Is Broken “Forget everything you know, or think you know, about online gaming. Like a blast of fresh air, Reality Is Broken blows away the tired stereotypes and reminds us that the human instinct to play can be harnessed for the greater good. With a stirring blend of energy, wisdom, and idealism, Jane McGonigal shows us how to start saving the world one game at a time.” —Carl Honoré, author of In Praise of Slowness and Under Pressure “Reality Is Broken is the most eye-opening book I read this year. With awe-inspiring ex pertise, clarity of thought, and engrossing writing style, Jane McGonigal cleanly exploded every misconception I’ve ever had about games and gaming. If you thought that games are for kids, that games are squandered time, or that games are dangerously isolating, addictive, unproductive, and escapist, you are in for a giant surprise!” —Sonja Lyubomirsky, Ph.D., professor of psychology at the University of California, Riverside, and author of The How of Happiness: A Scientific Approach to Getting the Life You Want “Reality Is Broken will both stimulate your brain and stir your soul. Once you read this remarkable book, you’ll never look at games—or yourself—quite the same way.” —Daniel H. Pink, author of Drive and A Whole New Mind “The path to becoming happier, improving your business, and saving the world might be one and the same: understanding how the world’s best games work. -

Artificial Intelligence, Ovvero Suonare Il Corpo Della Macchina O Farsi Suonare? La Costruzione Dell’Identità Audiovisiva Della Warp Records

Philomusica on-line 13/2 (2014) Artificial Intelligence, ovvero suonare il corpo della macchina o farsi suonare? La costruzione dell’identità audiovisiva della Warp Records Alessandro Bratus Dipartimento di Musicologia e Beni Culturali Università di Pavia [email protected] § A partire dai tardi anni Ottanta la § Starting from the late 1980s Warp Records di Sheffield (e in seguito Sheffield (then London) based Warp Londra) ha avuto un ruolo propulsivo Records pushed forward the extent nel mutamento della musica elettronica and scope of electronic dance music popular come genere di musica che well beyond its exclusive focus on fun non si limita all’accompagna-mento del and physical enjoinment. One of the ballo e delle occasioni sociali a esso key factors in the success of the label correlate. Uno dei fattori chiave nel was the creative use of the artistic successo dell’etichetta è stato l’uso possibilities provided by technology, creativo delle possibilità artistiche which fostered the birth of a di- offerte dalla tecnologia, favorendo la stinctive audiovisual identity. In this formazione di un’identità ben ca- respect a crucial role was played by ratterizzata, in primo luogo dal punto the increasing blurred boundaries di vista audiovisivo. Sotto questo profilo between video and audio data, su- un ruolo fondamentale ha giocato la bjected to shared processes of digital possibilità di transcodifica tra dati transformation, transcoding, elabora- audio e video nell’era digitale, poten- tion and manipulation. zialmente soggetti agli stessi processi di Although Warp Records repeatedly trasformazione, elaborazione e mani- resisted the attempts to frame its polazione. artistic project within predictable Nonostante la Warp Records abbia lines, its production –especially mu- ripetutamente resistito a ogni tentativo sic videos and compilations– suggests di inquadrare il proprio progetto arti- the retrospective construction of a stico entro coordinate prevedibili, i suoi consistent imagery. -

Multi-Cultural. Dinner" Feast Prez: Search Firm Gauges'baruch

::- ~.--.-.;::::-:-u•._,. _._ ., ,... ~---:---__---,-- --,.--, ---------- - --, '- ... ' . ' ,. ........ .. , - . ,. -Barueh:-Graduate.. -.'. .:~. Alumni give career advice to Baruch Students.· Story· pg.17 VOL. 74, NUMBER 8 www.scsu.baruch.cuny.edu DECEM·HER 9, 1998 Multi-Cultural. Dinner" Feast Prez: Search Firm Gauges'Baruch. Opinion By Bryan Fleck Representatives from Isaacson Miller, a national search firm based in -Boston and San Francisco, has been hired by the Presidential Search Committee, chaired by Kathleen M. Pesile, to search for candidates for a permanent presi dent at Baruch College. The open forum on December 7 was held in order for the search firm to field questions and get the pulse of the Baruch community. Interim president Lois Cronholm is _not a candidate, as it is against CUNY regulations for an interim --------- president to become a full-time pres- ident. The search firm will gather the initial candidates, who will be . further screened by the Presidential " Search Committee, but the final choice lies with the CUNY Board of Trustees.' According to David Bellshow, an ......-.. ~.. Isaacson-Miller representative, the '"J'", average search takes approximately ; six months. Among the search firm's experience in the field of education ----~- - ..... -._......... *- -_. - -- -- _._- ...... -_40_. '_"__ - _~ - f __•••-. __..... _ •• ~. _• in NY are Columbia University and ... --- -. ~ . --. .. - -. -~ -.. New York University. In ~additi6n,, , New plan calls'for total re'structuririg the search fum also works with GovernDlents small and large foundations and cor ofStudent porations. By Bryan Fleck at large, would be selected from any The purpose ofthe open forum was In an attempt to strengthen undergraduate candidate. for the representatives of Isaacson . -

THE WHITE STRIPES – the Hardest Button to Button (2003) ROLLING STONES – Like a Roling Stone (1995) I AM – Je Danse Le

MICHEL GONDRY DIRECTORS LABEL DVD http://www.director-file.com/gondry/dlabel.html DIRECTOR FILE http://www.director-file.com/gondry/ LOS MEJORES VIDEOCLIPS http://www.losmejoresvideoclips.com/category/directores/michel-gondry/ WIKIPEDIA http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michel_Gondry PARTIZAN http://www.partizan.com/partizan/home/ MIRADAS DE CINE 73 http://www.miradas.net/2008/n73/actualidad/gondry/gondry.html MIRADAS DE CINE 73 http://www.miradas.net/2008/n73/actualidad/gondry/rebobineporfavor1.html BACHELORETTE - BJORK http://www.director-file.com/gondry/bjork6.html THE WHITE STRIPES – The hardest button to button (2003) http://www.director-file.com/gondry/stripes3.html ROLLING STONES – Like a Roling Stone (1995) http://www.director-file.com/gondry/stones1.html I AM – Je danse le mia (1993) http://www.director-file.com/gondry/iam.html JEAN FRANÇOISE COHEN – La tour de Pise (1993) http://www.director-file.com/gondry/coen.html LUCAS - Lucas With the Lid off (1994) http://www.director-file.com/gondry/lucas.html CHRIS CUNNINGHAM DIRECTORS LABEL DVD http://www.director-file.com/cunningham/dlabel.html LOS MEJORES VIDEOCLIPS http://www.losmejoresvideoclips.com/category/directores/chris-cunningham/ POP CHILD http://www.popchild.com/Covers/video_creators/chris_cunningham.htm WEB PERSONAL AUTOR http://chriscunningham.com/ WIKIPEDIA http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chris_Cunningham ARTFUTURA http://www.artfutura.org/02/arte_chris.html APHEX TWIN – Come to Daddy (1997) http://www.director-file.com/cunningham/aphex1.html SPIKE JONZE WEB PERSONAL http://spikejonze.net/ -

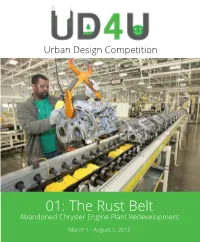

The Rust Belt Abandoned Chrysler Engine Plant Redevelopment

Urban Design Competition 01: The Rust Belt Abandoned Chrysler Engine Plant Redevelopment March 1 - August 1, 2015 About the Competition The aim of this International competition is to design a new urban area that will act as a catalyst in the heart of Kenosha, WI. The architecture and design of this new area should reflect contemporary design tendencies. The proposal must not only attend to the specific site but the design should also take into consideration the surrounding urban fabric and the impact your new design will have on on the sites surrounding and the entire Kenosha area as a whole. Competition Structure This is a single stage Competition with the aim of identifying the most appropriate proposal, which best satisfies the objective of the contest. Program and Design Criteria There is no specific program or design criteria. Even though the use is open ended all designs should address 4 aspects (History of the Site and City, The Sites Surrounding Urban Fabric, Industries of Kenosha, and Transportation Options) Competition Project Disclaimer This is an open international competition hosted by UD4U to generate progressive contemporary urban design ideas. There are no plans for any of the winners or participants projects to be built. Those Eligible to Participate Architects, Architecture Graduated, Engineers and Students. Interdisciplinary teams are also encouraged to enter the competition. Employees, staff, consultants, agents or family members of UD4U personnel, as well as employees, partners, friends, family, personnel, office practice or studios associated with any of the jurors are not allowed to participate in this competition. Restrictions There are no restrictions for this international competition. -

Motion As the Connection Between Audio and Visuals

Motion as the Connection Between Audio and Visuals and how it may inform the design of new audiovisual instruments Niall Moody Centre for Music Technology University of Glasgow UK [email protected] ABSTRACT by an examination of how motion may connect the two do- While it is often claimed that any connection between visual mains, and a number of example mappings between audio art and music is strictly subjective, this paper attempts to and visuals are presented. prove that motion can be used to connect the two domains in a manner that, though not objective in the true sense of 2. A BRIEF HISTORY OF AUDIO-VISUAL the word, will nevertheless be perceived in a similar fashion RELATIONS by multiple people. The paper begins with a brief history of This section will present a brief overview of what the au- attempts to link audio and visuals, followed by a discussion thor feels are the most significant attempts to link audio of Michel Chion’s notion of synchresis in film, upon which and visuals, beginning with Father Louis-Bertrand Castel’s the aforementioned claim is based. Next is an examination original ‘colour organ’ from the mid-1700s. The section is of motion in both audio and moving images, and a prelim- subdivided into various subgenres of, or threads within, au- inary look at the kind of mappings which may be possible. diovisual art, though it should be noted that there is con- As this is all done with a view to the design of new musi- siderable overlap between these sections, and they are in no cal, or audiovisual, instruments, the paper finishes with a way intended as comprehensive categories. -

Vacances De Proximité

population de la Communauté urbaine de Bordeaux au 1er juillet 2013 (estimation La Cub) 738 >Bienvenue à Martignas-sur-Jalle de proximité > Vacances 073 n°24 le Journal 3e trimestre 2013 Journal d’information de la Communauté urbaine de Bordeaux > L’Été métropolitain > L’Été ZAP DE CUB 4 PORTRAIT DOSSIER Blanca Li, chorégraphe 22 Voyages de proximité 8 BALADE DÉCRYPTAGE La Boucle Verte 24 Martignas sur Cub 14 D’UNE COMMUNE À L’AUTRE 26 LES DÉCHETS DE LA MÉTROPOLE 16 RENDEZ-VOUS 28 DES LIEUX PRATIQUE 29 Ambarès à l’horizon ! 16 PAROLE AUX GROUPES POLITIQUES 30 CARTE BLANCHE Les Requins Marteaux, éditeurs 20 ÉDITO © Claude Petit S’évader près de chez soi À l’heure où nous mettons sous presse, il peut paraître encore un peu risqué de parler d’été au vu des caprices de la météo qui n’épargnent pas le ciel bordelais. Il n’empêche, nous apprécions d’autant chaque rayon de soleil et recoin de ciel bleu à leur juste valeur. Avec les vacances scolaires, la saison des concerts et des animations estivales est de retour. Pour la deuxième année, La Cub a choisi de mettre à l’honneur tout ce qui fait ici et aujourd’hui la chaleur et l’attrait de notre territoire. Sous la bannière de L’Été métropolitain, le meilleur de ce qu’offrent les communes de La Cub, tant à ses habitants qu’à nos visiteurs, est exposé dans sa richesse et sa diversité. Il suffit de compulser le programme pour s’en convaincre : plus d’une quarantaine d’événements, concerts, soirées thématiques, festivals en tout genre, mais aussi balades et itinéraires de randonnées, nuitées dans les refuges urbains… Plus que jamais, il est possible de s’évader et de passer un été de découverte, de dépaysement et d’enrichissement à deux pas de chez soi. -

Business AD-Vantage

PAGE 8 PRESS & DAKOTAN n MONDAY, DECEMBER 28, 2015 ecutor who parlayed his handling Bobbi Kris- it to Me,” on the hit comedy show. a prominent figure in Margaret vehicles ranging from the beautiful of the Charles Manson trial into tina Brown, Sept. 3. Thatcher’s government but helped to the outrageous. Nov. 5. a career as a bestselling author. 22. Daughter of William Grier, 89. Psychiatrist bring about her downfall after they Gunnar Hansen, 68. He Deaths June 6. singers Whitney who co-authored the groundbreak- parted ways over policy toward played the iconic villain Leather- From Page 7 Christopher Lee, 93. Actor Houston and ing 1968 book, “Black Rage,” Europe. Oct. 9. face in the original “Texas Chain who brought dramatic gravitas Bobby Brown, which offered the first psychologi- Jerry Parr, 85. Secret Ser- Saw Massacre” film. Nov. 7. Pan- and aristocratic bearing to screen she was raised cal examination of black life in the vice agent credited with saving creatic cancer. the hail of snowballs and shower villains from Dracula to the wicked in the shadow United States. Sept. 3. President Ronald Reagan’s life Helmut Schmidt, 96. Former of boos that rained down on him. wizard Saruman in “The Lord of of fame and Martin Milner, 83. His whole- on the day he was shot outside a chancellor who guided West April 30. the Rings” trilogy. June 7. shattered by some good looks helped make Washington hotel. Oct. 9. Germany through economic turbu- Vincent Musetto, 74. Veteran Walter Dale the loss of her him the star of two hugely popular Richard Heck, 84. -

Brand New Cd & Dvd Releases 2006 6,400 Titles

BRAND NEW CD & DVD RELEASES 2006 6,400 TITLES COB RECORDS, PORTHMADOG, GWYNEDD,WALES, U.K. LL49 9NA Tel. 01766 512170: Fax. 01766 513185: www. cobrecords.com // e-mail [email protected] CDs, DVDs Supplied World-Wide At Discount Prices – Exports Tax Free SYMBOLS USED - IMP = Imports. r/m = remastered. + = extra tracks. D/Dble = Double CD. *** = previously listed at a higher price, now reduced Please read this listing in conjunction with our “ CDs AT SPECIAL PRICES” feature as some of the more mainstream titles may be available at cheaper prices in that listing. Please note that all items listed on this 2006 6,400 titles listing are all of U.K. manufacture (apart from Imports which are denoted IM or IMP). Titles listed on our list of SPECIALS are a mix of U.K. and E.C. manufactured product. We will supply you with whichever item for the price/country of manufacture you choose to order. ************************************************************************************************************* (We Thank You For Using Stock Numbers Quoted On Left) 337 AFTER HOURS/G.DULLI ballads for little hyenas X5 11.60 239 ANATA conductor’s departure B5 12.00 327 AFTER THE FIRE a t f 2 B4 11.50 232 ANATHEMA a fine day to exit B4 11.50 ST Price Price 304 AG get dirty radio B5 12.00 272 ANDERSON, IAN collection Double X1 13.70 NO Code £. 215 AGAINST ALL AUTHOR restoration of chaos B5 12.00 347 ANDERSON, JON animatioin X2 12.80 92 ? & THE MYSTERIANS best of P8 8.30 305 AGALAH you already know B5 12.00 274 ANDERSON, JON tour of the universe DVD B7 13.00