Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mifepristone

Mifepristone sc-203134 Material Safety Data Sheet Hazard Alert Code EXTREME HIGH MODERATE LOW Key: Section 1 - CHEMICAL PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION PRODUCT NAME Mifepristone STATEMENT OF HAZARDOUS NATURE CONSIDERED A HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCE ACCORDING TO OSHA 29 CFR 1910.1200. NFPA FLAMMABILITY1 HEALTH0 HAZARD INSTABILITY0 SUPPLIER Company: Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Address: 2145 Delaware Ave Santa Cruz, CA 95060 Telephone: 800.457.3801 or 831.457.3800 Emergency Tel: CHEMWATCH: From within the US and Canada: 877-715-9305 Emergency Tel: From outside the US and Canada: +800 2436 2255 (1-800-CHEMCALL) or call +613 9573 3112 PRODUCT USE ■ Steroid. Abortifacient steroid. Progesterone receptor antagonist. Binds strongly to progesterone and glucocorticoid recptors, weakly to androgen receptors, but has no anti-oestrogenic or mineralocorticoid activity. Inhibits ovulation when given in the late follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. SYNONYMS C29-H35-N-O2, C29-H35-N-O2, "estra-4, 9-diene-3-one, ", "estra-4, 9-diene-3-one, ", "11-[4-(dimethylamino)phenyl]-17- hydroxy-17-(1-propynyl)-, (11beta, ", 17beta)-, "11-[4-(dimethylamino)phenyl]-17-hydroxy-17-(1-propynyl)-, (11beta, ", 17beta)-, 17beta-hydroxy-11beta-(4-dimethylaminophenyl-1)-, "17alpha-(prop-1-ynyl)oestra-4, 9-dien-3-one", "17alpha-(prop- 1-ynyl)oestra-4, 9-dien-3-one", Mifegyn, R-38486, R-38486, "RU 486", RU-486-6, "RU 38486", "abortifacient oestrogen/ estrogen steroid", "morning after pill" Section 2 - HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION CANADIAN WHMIS SYMBOLS EMERGENCY OVERVIEW RISK May impair fertility. May cause harm to the unborn child. Toxic to aquatic organisms, may cause long-term adverse effects in the aquatic environment. -

The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented In

Insignificance Given Meaning: The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Masako Inamoto Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Edgar Torrance Professor Naomi Fukumori Professor Shelley Fenno Quinn Copyright by Masako Inamoto 2010 Abstract Kita Morio (1927-), also known as his literary persona Dokutoru Manbô, is one of the most popular and prolific postwar writers in Japan. He is also one of the few Japanese writers who have simultaneously and successfully produced humorous, comical fiction and essays as well as serious literary works. He has worked in a variety of genres. For example, The House of Nire (Nireke no hitobito), his most prominent work, is a long family saga informed by history and Dr. Manbô at Sea (Dokutoru Manbô kôkaiki) is a humorous travelogue. He has also produced in other genres such as children‟s stories and science fiction. This study provides an introduction to Kita Morio‟s fiction and essays, in particular, his versatile writing styles. Also, through the examination of Kita‟s representative works in each genre, the study examines some overarching traits in his writing. For this reason, I have approached his large body of works by according a chapter to each genre. Chapter one provides a biographical overview of Kita Morio‟s life up to the present. The chapter also gives a brief biographical sketch of Kita‟s father, Saitô Mokichi (1882-1953), who is one of the most prominent tanka poets in modern times. -

Topic N 26: Organization of the Gynecological Hospital. Research Methods in Gynecology. the Main Indicator of the Effectiveness

Таблица 1.Перечень заданий по гинекологии для студентов 5 курса лечебного факультета за VII – учебный семестр, обучающихся на английском языке. Topic N 26: Organization of the gynecological hospital. Type The code Research methods in gynecology. Ф The main indicator of the effectiveness of a preventive В 001 gynecological examination of working women is О Г number of women examined О Б the number of gynecological patients taken to the dispensary О В the number of women referred for treatment in a sanatorium the proportion of identified gynecological patients among the О А examined women О Д correct a) and б) The role of examination gynecological rooms in polyclinics В 002 consists, as a rule О Г in the medical examination of gynecological patients О Б in the examination and observation of pregnant women О В in conducting periodic medical examinations О А in coverage of preventive examinations of unemployed women О Д correct в) and г) Women's consultation is a structural unit 1) maternity hospital В 003 2) clinics 3) medical and sanitary part 4) sanatorium-preventorium О Б correct 1, 2, 3 О А correct 1, 2 О В all answers are correct О Г correct only 4 О Д all answers are wrong The concept of "family planning" most likely means activities that help families В 004 1) avoid unwanted pregnancy 2) adjust the intervals between pregnancies 3) to produce the desired children 4) increase the birth rate О А correct 1, 2, 3 О Б correct 1, 2 О В all answers are correct О Г correct only 4 О Д all answers are wrong In a women's consultation it is advisable -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

O-1 the Epithelial-To-Mesenchymal Transition Protein Periostin Is

Virchows Arch (2008) 452 (Suppl 1):S1–S286 DOI 10.1007/s00428-008-0613-x O-1 O-2 The epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition protein Squamous cell carcinoma of the lung: polysomy periostin is associated with higher tumour stage of chromosome 7 and wild type of exon 19 and 21 and grade in non-small cell lung cancer were defined for the EGFR gene Alex Soltermann; Laura Morra; Stefanie Arbogast; Vitor Sousa; Maria Silva; Ana Alarcão; Patrícia Peter Wild; Holger Moch, Glen Kristiansen Couceiro; Ana Gomes; Lina Carvalho Institute for Surgical Pathology Zürich, Switzerland Instituto de Anatomia Patológica - Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Coimbra, Portugal Background: The epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is vital for morphogenesis and has been implicated BACKGROUND: The use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer invasion. EMT of carcinoma cells can be defined after first line chemotherapy, induced several studies to by morphological trans-differentiation, accompanied by determine molecular characteristics in non-small-cell lung permanent cytosolic overexpression of mesenchymal pro- cancer to predict the response to those drugs. teins, which are normally expressed in the peritumoural The present study was delineated to clarify the status of stroma. We aimed for correlating the expression levels of EGFR gene by Fluorescence in situ Hibridization(FISH), the EMT indicator proteins periostin and vimentin with Polimerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Immunohistochem- clinico-pathological parameters of non-small cell lung ical protein expression in 60 cases of squamous cell cancer (NSCLC). Method: 538 consecutive patients with carcinoma of the lung after surgical resection of tumours surgically resected NSCLC were enrolled in the study and a in stages IIb/IIIa. -

Prevalence and Factors Associated with Cracked Nipples in the First Month Postpartum

Santos et al. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2016) 16:209 DOI 10.1186/s12884-016-0999-4 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Prevalence and factors associated with cracked nipples in the first month postpartum Kamila Juliana da Silva Santos1,3*, Géssica Silva Santana1, Tatiana de Oliveira Vieira1, Carlos Antônio de Souza Teles Santos1, Elsa Regina Justo Giugliani2 and Graciete Oliveira Vieira1 Abstract Background: To assess the prevalence and factors associated with the occurrence of cracked nipples in the first month postpartum. Methods: This was a cross-sectional study nested in a cohort of mothers living in Feira de Santana, state of Bahia, northeastern Brazil. Data from 1,243 mother-child dyads assessed both at the maternity ward and 30 days after delivery were analyzed. The association between cracked nipples as reported by mothers and their possible determinants was analyzed using Poisson regression in a model where the variables were hierarchically organized into four levels: distal (individual characteristics), distal intermediate (prenatal characteristics), proximal intermediate (delivery characteristics), and proximal (postnatal characteristics). Results: The prevalence of cracked nipples was 32 % (95 % confidence interval [95 % CI] 29.4–34.7) in the first 30 days postpartum. The following factors showed significant association with the outcome: poor breastfeeding technique (prevalence ratio [PR] = 3.18, 95 % CI 2.72–3.72); breast engorgement (PR = 1.70, 95 % CI 1.46–1.99); birth in a maternity ward not accredited by the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (PR = 1.51, 95 % CI 1.15–1.99); cesarean section (PR = 1.33, 95 % CI 1.13–1.57); use of a feeding bottle (PR = 1.29, 95 % CI 1.06–1.55); and higher maternal education level (PR = 1.23, 95 % CI 1.04–1.47). -

Financialization and Industrial Policies in Japan and Korea

CEAFJP Discussion Paper Series 16-02 CEAFJPDP Financialization and industrial policies in Japan and Korea Evolving complementarities and loss of institutional capabilities Sébastien Lechevalier EHESS, CCJ-FFJ Pauline Debanes EHESS, CCJ-FFJ Wonkyu Shin Kyung Hee University April 2016 http://ffj.ehess.fr CEAFJP Discussion Paper Series 16-06 Abstract The purpose of this article is to analyze the revival of industrial policies from the late 2000s in Japan and Korea and their limitations. Our approach has two major characteristics. First, we adopt the perspective of historical institutionalism to focus on the relation between IPs and financial systems and study their evolution over the last 40 years. Second, by mobilizing the concepts of institutional complementarities and hierarchy, we discuss the limits of this revival in a context of liberalized financial systems, to which IPs have contributed. Our major result is that, in the context of financialization, past complementarities of the developmental state have weakened and contradictions have arisen. It resulted in a restructuration of state capabilities to design and implement IPs, and to its inability to subordinate finance to its goals, despite the discourses and ambitions of governments. However, and this is our second result, comparison between Japan and Korea also allows us to identify some significant differences that may explain diverging trends in terms of the deindustrialization and internationalization of these two economies. Key words: Institutional complementarities, institutional hierarchy, developmental state, structural reforms, liberalization JEL: 025, 053, P110, P16, P51 Centre d'études avancées franco-japonais de Paris 2 CEAFJP Discussion Paper Series 16-06 1. Introduction Industrial policies (IPs) in OECD countries have undergone a remarkable evolution in their conception, framing and practices during the last four decades (Andreoni, 2014; Chang et al., 2013). -

PREGNANCY a to Z

PREGNANCY A to Z PREGNANCY A to Z A simple guide to pregnancy, its investigations, stages, complications, anatomy, terminology and conclusion Dr. Warwick Carter 2 PREGNANCY A to Z The pregnant woman has the amazing ability to turn hamburgers and vegetables into a baby. The most important thing you ever do in life is choose your parents. 3 PREGNANCY A to Z PREGNANCY The first sign that a woman may be pregnant is that she fails to have a menstrual period when one is normally due. At about the same time as the period is missed, the woman may feel unwell, unduly tired, and her breasts may become swollen and uncomfortable. A pregnant woman should not smoke because smoking adversely affects the baby's growth, and smaller babies have more problems in the early months of life. The chemicals inhaled from cigarette smoke are absorbed into the bloodstream and pass through the placenta into the baby's bloodstream, so that when the mother has a smoke, so does the baby. Alcohol should be avoided especially during the first three months of pregnancy when the vital organs of the foetus are developing. Later in pregnancy it is advisable to have no more than one drink every day with a meal. Early in the pregnancy the breasts start to prepare for the task of feeding the baby, and one of the first things the woman notices is enlarged tender breasts and a tingling in the nipples. With a first pregnancy, the skin around the nipple (the areola) will darken, and the small lubricating glands may become more prominent to create small bumps. -

Inciting Difference and Distance in the Writings of Sakiyama Tami, Yi Yang-Ji, and Tawada Yōko

Inciting Difference and Distance in the Writings of Sakiyama Tami, Yi Yang-ji, and Tawada Yōko Victoria Young Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of East Asian Studies, School of Languages, Cultures and Societies March 2016 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2016 The University of Leeds and Victoria Young iii Acknowledgements The first three years of this degree were fully funded by a Postgraduate Studentship provided by the academic journal Japan Forum in conjunction with BAJS (British Association for Japanese Studies), and a University of Leeds Full Fees Bursary. My final year maintenance costs were provided by a GB Sasakawa Postgraduate Studentship and a BAJS John Crump Studentship. I would like to express my thanks to each of these funding bodies, and to the University of Leeds ‘Leeds for Life’ programme for helping to fund a trip to present my research in Japan in March 2012. I am incredibly thankful to many people who have supported me on the way to completing this thesis. The diversity offered within Dr Mark Morris’s literature lectures and his encouragement as the supervisor of my undergraduate dissertation in Cambridge were both fundamental factors in my decision to pursue further postgraduate studies, and I am indebted to Mark for introducing me to my MA supervisor, Dr Nicola Liscutin. -

062160 MCHR NEWS #24 FA 25/11/05 4:00 PM Page 4

062160 MCHR NEWS #24 FA 25/11/05 4:00 PM Page 4 Department of Communities acknowledged MOSAIC mentor mother co-ordinator, and MOSAIC MOSAIC’s strong community partnership Jan Wiebe, MOSAIC research officer. They with maternal and child health nurse teams, are pictured here, together with Chief divisions of general practice, and women’s Investigators Angela Taft, Rhonda Small implementation health services in the north-west region of and Judith Lumley, and Kim Hoang, our Melbourne. research and project officer with the – funded The Hon Mary Delahunty MLA, Minister for Vietnamese community. Women's Affairs, will launch MOSAIC on Project update: MOSAIC has now at last! Angela Taft 12 December at Richmond Town Hall. completed training with six maternal and The launch will provide a wonderful child health nurse teams and 21 GPs from MCHR NEWS We have been outlining the gradual opportunity to celebrate the project with 17 general practices. These nurse teams development of the MOSAIC (Mothers’ our community partners and the mentor and practices have been randomised to Advocates In the Community) cluster mothers who have all supported MOSAIC comparison and intervention arms of the randomised trial over previous centre with such enthusiasm and commitment trial and referrals to the study have now newsletters. Readers will know that during our quest for funding. commenced. Further GP recruitment and Della Forster’s thesis Breastfeeding – Jane Yelland’s studies culminated in her MOSAIC aims to evaluate the role of making a difference: predictors, women’s thesis Changing maternity care: an evaluation MOSAIC has also recently welcomed two training will continue early in 2006. -

Table of Contents

Introduction to NAC OSCE General Information............................................................... Registration for NAC OSCE................................................ Fees......................................................................................... Examination station............................................................... NAC OSCE scoring.............................................................. Sample of Therapeutic written test........................................ Sample clinical case station.................................................... Therapeutic Guidelines Medicine Cardiology.............................................................................. Dermatology........................................................................... Endocrinology........................................................................ Gastroentermogy.................................................................... Hematology............................................................................ Infectious Diseases................................................................. Neurology............................................................................... Otolaryngology...................................................................... Pulmonology.......................................................................... Rheumatology........................................................................ Nephrology/Urology............................................................. -

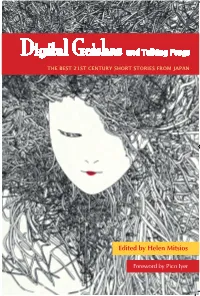

Digital Geishas Sample 4.Pdf

Literature/Asian Studies Digital Geishas Digital Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs THE BEST 21ST CENTURY SHORT STORIES FROM JAPAN Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs With a foreword by Pico Iyer and Talking Frogs THE BEST 21ST CENTURY SHORT STORIES FROM JAPAN This collection of short stories features the most up-to-date and exciting writing from the most popular and celebrated authors in Japan today. These wildly imaginative and boundary-bursting stories reveal fascinating and unexpected personal responses to the changes raging through today’s Japan. Along with some of the THE BEST 21 world’s most renowned Japanese authors, Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs includes many writers making their English-language debut. ST “Great stories rewire your brain, and in these tales you can feel your mind C E shifting as often as Mizue changes trains at the Shinagawa station in N T ‘My Slightly Crooked Brooch…’ The contemporary short stories in this URY SHO collection, at times subversive, astonishing and heart-rending, are brimming with originality and genius.” R —David Dalton, author of Pop: The Genius of Andy Warhol T STO R “Here are stories that arrive from our global future, made from shards IES FR of many local, personal pasts. In the age of anime, amazingly, Japanese literature thrives.” O M JAPAN —Paul Anderer, Professor of Japanese, Columbia University About the Editor H EDITED BY Helen Mitsios is the editor of New Japanese Voices: The Best Contemporary Fiction from Japan, which was twice listed as a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice. She has recently co-authored the memoir Waltzing with the Enemy: A Mother and Daughter Confront the Aftermath of the Holocaust.