Mgraham Callaloo.Pdf (2.427Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

158 Kansas History the Hard Kind of Courage: Labor and Art in Selected Works by Langston Hughes, Gordon Parks, and Frank Marshall Davis

Gordon Parks’s American Gothic, Washington, D.C., which captures government charwoman Ella Watson at work in August 1942. Photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 36 (Autumn 2013): 158–71 158 Kansas History The Hard Kind of Courage: Labor and Art in Selected Works by Langston Hughes, Gordon Parks, and Frank Marshall Davis by John Edgar Tidwell hen and in what sense can art be said to require a “hard kind of courage”? At Wichita State University’s Ulrich Museum, from September 16 to December 16, 2012, these questions were addressed in an exhibition of work celebrating the centenary of Gordon Parks’s 1912 birth. Titled “The Hard Kind of Courage: Gordon Parks and the Photography of the Civil Rights Era,” this series of deeply profound images offered visual testimony to the heart-rending but courageous sacrifices made by Freedom Riders, the bombing victims Wat the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, the energized protesters at the Great March on Washington, and other participants in the movement. “Photographers of the era,” the exhibition demonstrated, “were integral to advancing the movement by documenting the public and private acts of racial discrimination.”1 Their images succeeded in capturing the strength, fortitude, resiliency, determination, and, most of all, the love of those who dared to step out on faith and stare down physical abuse and death. It is no small thing that all this was done amidst the challenges of being a black artist or writer seeking self-actualization in a racially charged era. -

Manhattan, Kansas African American History Trail Self-Guided Driving

1 Manhattan, Kansas African American History Trail Self-Guided Driving Tour July 2020 This self-guided driving tour was developed by the staff of the Riley County Historical Museum to showcase some of the interesting and important African American history in our community. You may start the tour at the Riley County Historical Museum, or at any point along to tour. Please note that most sites on the driving tour are private property. Sites open to the public are marked with *. If you have comments or corrections, please contact the Riley County Historical Museum, 2309 Claflin Road, Manhattan, Kansas 66502 785-565-6490. For additional information on African Americans in Riley County and Manhattan see “140 Years of Soul: A History of African-Americans in Manhattan Kansas 1865- 2005” by Geraldine Baker Walton and “The Exodusters of 1879 and Other Black Pioneers of Riley County, Kansas” by Marcia Schuley and Margaret Parker. 1. 2309 Claflin Road *Riley County Historical Museum and the Hartford House, open Tuesday through Friday 8:30 to 5:00 and Saturday and Sunday 2:00 to 5:00. Admission is free. The Museum features changing exhibits on the history of Riley County and a research archive/library open by appointment. The Hartford House, one of the pre-fabricated houses brought on the steamboat Hartford in 1855, is beside the Riley County Historical Museum. 2. 2301 Claflin Road *Goodnow House State Historic Site, beside the Riley County Historical Museum, is open Saturday and Sunday 2:00 to 5:00 and when the Riley County Historical Museum is open and staff is available. -

The Vlakh-Bor™,^ • University of Hawaii

THE VLAKH-BOR™,^ • UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII-. n ■ ■ LIBRARY -' - .. ........__________________ Page Five HONO., T.H.52 8-4-49 ~ Sec. 562, P. L. & R. .U. S. POSTAGE Single Issue 1* PAID The Newspaper Hawaii Needs Honolulu, T. H. 10c $5.00 per year Permit No. 189 by subscription Vol. 1, No. 40 PUBLISHED EVERY THURSDAY May SMW Advertiser Does It Again! TH LABOR LOSES $100,000 BY LEGISLATIVE SLOTH "Red” Smew Is DamonDemos Solons Improve 29 Yews Old Protest Big WCL; Provide No Hike In 1 axes Staff Addition By STAFF WRITER Land that formerly cost own Working-people in Hawaii will ers in Damon Tract taxes of three be deprived of $100,000 rightfully cents per square foot has this year due them next • year, because the been assessed at 10 cents per square legislature failed to implement the foot, and as a result, a number improved Workmen’s Compensa of Damon Tract people are indig tionLaw by providing a staff ca- . nantly and actively protesting. pable of administering it. That , “The .increase,” says Henry Ko-. is the opinion of William- M. -Doug kona, Damon Tract resident who las of the Bureau of Workmen’s leads the movement, “is from 100 Compensation. v. ■ . to 400 per cent, varying with the The platforms of both parties number of improvements on the included statements approving ad place. The assessor says it’s be- ditions to the Bureau’s.very small . cause Damon Tract has become staff, no additions >were made, a - residential district. Before, it though some very substantial im was assessed as farming land.-” provements .were realized. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 115 646 SP 009 718 TITLE Multi-Ethnic

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 115 646 SP 009 718 TITLE Multi-Ethnic Contributions to American History.A Supplementary Booklet, Grades 4-12. INSTITUTION Caddo Parish School Board, Shreveport, La. NOTE' 57p.; For related document, see SP 009 719 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$3.32 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS Achievement; *American History; *Cultural Background; Elementary Secondary Education; *Ethnic Groups; *Ethnic Origins; *Teaching Guides IDENTIFIERS *Multicultural Education ABSTRACT This booklet is designed as a teacher guide for supplementary use in the rsgulat social studies program. It lists names and contributions of Americans from all ethnic groups to the development of the United States. Seven units usable at three levels (upper elementary, junior high, and high school) have been developed, with the material arranged in outline form. These seven units are (1) Exploration and Colonization;(2) The Revolutionary Period and Its Aftermath;(3) Sectionalism, Civil War, and Reconstruction;(4) The United States Becomes a World Power; (5) World War I--World War II; (6) Challenges of a Transitional Era; and (7) America's Involvement in Cultural Affairs. Bibliographical references are included at the end of each unit, and other source materials are recommended. (Author/BD) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * via the ERIC Document-Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * responsible for the qUa_lity of the original document. Reproductions * supplied-by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original. -

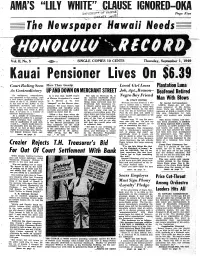

HONOLULU.Rtcord

AMA’S “LILY WHITE” CLAUSE IGNORED -OKA Of HAM • • Page Five ^The Newspaper Hawaii Needs HONOLULU.RtCORD. Vol. II, No. 5 SINGLE COPIES 10 CENTS Thursday, September 1, 1949 Kauai Pensioner Lives On $6.39 Court R uling Seen More Than Gossip: Local Girl Loses Plantation Luna As Contradictory UP AND DOWN ON MERCHANT STREET Job,Apt^Reason-- Deafened Retired “So ambiguous, contradictory, Is it true that 125,000 shares The talk on Merchant St. is Negro Boy Friend and uncertain is this ruling,” says of Matson Navigation Co. owned the reported $40,000,000 which a local lawyer, speaking of the' de the California and Hawaiian Re By STAFF WRITER Man With Blows cision of the U. S. District Court by C. Brewer & Co. were fining Corp, borrowed from the “dumped” on the Brewer plan Because her boy friend is a Ne By Special Correspondence in the case-of-the ILWU vs. the Prudential Life Insurance Co. gro—a soldier and a veteran of legislature, governor and others, tations? We hear there’s loud LIHUE, Kauai—An old Jap A reliable source says that this action in Germany in World War anese pensioner of the Koloa- “that it can be interpreted only grumbling and rumbling going money paid for two-thirds of II—Sharon Wiechel, 22, was fired by the judges who wrote it. Even on inside and outside the walled this year’s sugar crop now in Grove Farm was retired by the then, it is* open to a number of citadel on lower Fort St. from her job at American Legion company: at,$14.04 a month. -

A Critical Analysis of the Black President in Film and Television

“WELL, IT IS BECAUSE HE’S BLACK”: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE BLACK PRESIDENT IN FILM AND TELEVISION Phillip Lamarr Cunningham A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2011 Committee: Dr. Angela M. Nelson, Advisor Dr. Ashutosh Sohoni Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Michael Butterworth Dr. Susana Peña Dr. Maisha Wester © 2011 Phillip Lamarr Cunningham All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Ph.D., Advisor With the election of the United States’ first black president Barack Obama, scholars have begun to examine the myriad of ways Obama has been represented in popular culture. However, before Obama’s election, a black American president had already appeared in popular culture, especially in comedic and sci-fi/disaster films and television series. Thus far, scholars have tread lightly on fictional black presidents in popular culture; however, those who have tend to suggest that these presidents—and the apparent unimportance of their race in these films—are evidence of the post-racial nature of these texts. However, this dissertation argues the contrary. This study’s contention is that, though the black president appears in films and televisions series in which his presidency is presented as evidence of a post-racial America, he actually fails to transcend race. Instead, these black cinematic presidents reaffirm race’s primacy in American culture through consistent portrayals and continued involvement in comedies and disasters. In order to support these assertions, this study first constructs a critical history of the fears of a black presidency, tracing those fears from this nation’s formative years to the present. -

Articles 2015 年 6 月 第 48 巻

日本大学生産工学部研究報告B Articles 2015 年 6 月 第 48 巻 Wright and Hughes: Chicago and Two Major African American Writers Toru KIUCHI* and Noboru FUKUSHIMA* (Received December 16, 2014) Abstract The Chicago Renaissance has long been considered a less important literary movement for American modernism than the Harlem Renaissance. The differences between the two movements have to do not only with history, but with aesthetics. While the Harlem Renaissance began in the 1920s—flourishing during the decade, but fading during the 30s in the throes of the Depression—the Chicago Renaissance had its origin in the turn of the nineteenth century, from 1890 to 1920, gathering momentum in the 30s, and paving the way for modern and postmodern realism in American literature ever since. Theodore Dreiser was the leader for the first period of the movement, and Richard Wright was the most influential figure for the second period. The first section of this article will examine not only the continuity that existed between the two periods in the writers’ worldviews but also the techniques they shared. To portray Chicago as a modern, spacious, cosmopolitan city, the writers of the Chicago Renaissance sought ways to reject traditional subject matter and form. The new style of writing yielded the development of a distinct cultural aesthetic that reflected ethnically diverse sentiments and aspirations. The panel discussion will focus on the fact that while the Harlem Renaissance was dominated by African American writers, the Chicago Renaissance thrived on the interactions between African and European American writers. Much like modern jazz, writings in the Chicago Renaissance became the hybrid, cross-cultural product of black and white Americans. -

G-MEN QUIZ SPEIKER Negro Who Led ' Fata Methods Soak-The-Poor Group Talk Is ■ Hit by Verdict Lax

^Typical Mainland Haole” by f. M. Davis ag? PAGE FIVE WB V -* MISS JANET BELL ■___________ :________________________________________________________________________________ ~ UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII ■ < ' | Sec. 5G2, P.' L. '& R. LIBRARY Single Issue IU. S. POSTAGE HONO., T.H.52 8-4^49 , . J T "KT / K PAID jper Hawaii Needs 10c - Honolulu, T. H. $6.00 per year 8 Permit . No. 189 by subscription ■ VoL I j No. 26 PUBLISHED EVERY THURSDAY . January 27, 1949 <»» G-MEN QUIZ SPEIKER Negro Who Led ' Fata Methods Soak-the-Poor Group Talk Is ■ Hit By Verdict lax. System Of Questioned First 'Of Incest Jury ■ 1 erritory Hit It was a coincidence, nothinG., more, says William EubanK, that “I shudder to thinK how many Hawaii has a “soaK the poor” the FBI Questioned him for ,two innocent people in the Territory tax system. ReGressive, or flat and a half-hours on the afternoon may have been convicted of crimes rate taxes accounted for 94.4 per of Monday; Jan. 17, just before he because they siGned confessions cent of the Territory’s tax revenue was to lead a discussion on the they didn’t comprehend.” durinG the past, fiscal year, ac situation of NeGroes in Hawaii at That was the reflection of At cordinG to a study made by, the the New Era 'Church, CHA-3. •• torney Myer C. Symonds on last Joint Tax Research Committee, The discussion, was held un weeK’s case in Hilo in which he composed of 10 orGanizations with der the auspices of the ’Fellow defended Felipe Batulanon, an approximately 60,000 members. -

“Me and My Chauffeur Blues”—Memphis Minnie (1941) Added to the National Registry: 2019 Essay by Paul Garon (Guest Post)*

“Me and My Chauffeur Blues”—Memphis Minnie (1941) Added to the National Registry: 2019 Essay by Paul Garon (guest post)* Memphis Minnie By the early 1940s, when Memphis Minnie cut her hit song, the African American music tradition of the blues, which had arisen in the early 1920s, was still going strong. Within that tradition, Minnie had developed a reputation as a stunning and popular blues entertainer. Her newest hit, “Me and My Chauffeur Blues,” recorded May 21, 1941, used the tune of “Good Morning School Girl,” cut in 1937 by Sonny Boy (John Lee) Williamson. She revitalized the melody, creating a song that Langston Hughes would go on to later call one of his favorites. By that time, for years, record companies who recorded blues singers like Sonny Boy and Memphis Minnie had been releasing material marketed to African Americans on special numerical “race” series. This special numbering helped to point the dealers toward their target audience. Minnie’s, and her husband Joe McCoy’s, early records were issued on three different labels’ race series: Columbia’s 13/14000 series; Vocalion’s1000 series and Decca 7000 series, where the couple’s last duets would be issued. But Memphis Minnie wasn’t always called Memphis Minnie. Born Lizzie Douglas in northwest Mississippi in 1897, she rejected the name Lizzie in favor of the nickname “Kid,” so “Kid Douglas” she was until a Columbia records talent scout found her and her husband playing in Memphis and sent them to New York to make their first recordings. It was a Columbia producer who renamed them Kansas Joe and Memphis Minnie. -

Loren Collins 303 Peachtree Street, Suite 4100 Atlanta, GA 30308 I: O •TI I~ February 5, I2014 I

Loren Collins 303 Peachtree Street, Suite 4100 Atlanta, GA 30308 i: o •TI i~ February 5, i2014 i Office of General.Counsel ; — Federal Election Commission 999 E. Street, N.W, Washington D.C. 20463 MUK#- ^779 To whom it may concern: Enclosed, is ah original signed Complaint documenting violations of federal laws and regulations which I believe may have occurred. The Complaint is accompanied by several exhibits, and I have included two additional copies of the Complaint and its attachments. I can be reached at the above address, or by e-mail at [email protected]. Thank yoii. •Lbren doljinS; ? omm FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION CD PNJ ""T :.7' In the matter of: j W Joel Gilbert S ; # DFMRF.LLC MURNo. ^uir^y * Ifr -: - Highway 61 Entertainment, LLC ——• * ' •' COMPLAINT ; 'F- r- -- 1. This Complaint is brought before the Federal Election Commission ("FEC") seeking an immediate investigation and enforcement action against Joel Gilbert, DFMRF LLC, and Highway 61 Entertainment LLC for direct and serious violations of the Federal Elections Campaign Act ("FECA"). 2. Joel Gilbert is a filmmaker and is the owner and president of the companies DFMRF LLC and Highway 61 Entertainment LLC. His mailing address is 365 E. Avenida De Los Arboles, Ste. 1000, Thousand Oaks, California, 91360. 3. DFMRF LLC is a limited liability corporation registered to do business in the state of California. The company's registered address is 1875 Century Park East #1500, Los Angeles, California, 90067, and its registered agent is Joel Gilbert. It was incorporated «•on July 13,2012. 4. Highway 61 Entertainment LLC is a limited liability corporation registered to do business in the state of California, and is primarily engaged in the business of producing and distributing films. -

PAPERS: the ASSOCIATED NEGRO PRESS, 1918-1967 Part Two Associated Negro Press Organizational Files, 1920-1966

THE CLAUDE A. BARNETT PAPERS: THE ASSOCIATED NEGRO PRESS, 1918-1967 Part Two Associated Negro Press Organizational Files, 1920-1966 UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES: Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections August Meier and Elliott Rudwick , General Editors THE CLAUDE A. BARNETT PAPERS: The Associated Negro Press, 1918-1967 Part Two Associated Negro Press Organizational Files, 1920-1966 Edited by August Meier and Elliott Rudwick Microfilmed from the holdings of the Chicago Historical Society A Microfilm Project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS of AMERICA, INC. 44 North Market Street • Frederick, Maryland 21701 NOTE ON SELECTIONS Portions of the Claude A. Barnett papers at the Archives and Manuscripts Depart- ment of the Chicago Historical Society do not appear in this microfilm edition. The editors chose not to include African and other foreign relations materials (such as the records of the World News Service) in the microfilm and to film only the Ameri- can categories of the Barnett papers that hold the greatest potential research value. Materials of negligible or specialized research interest that were not microfilmed include ANP financial records and routine newsgathering correspondence. Ques- tions about the Barnett papers should be directed to the Archives and Manuscripts Department. Photographs, dating primarily from the 1940s to the 1960s, also are not included in this microfilm set. They are housed in the Prints and Photographs Department of the Chicago Historical Society. Copyright © 1985 by the Chicago Historical Society. All rights reserved. ISBN 0-89093-739-7. TABLE OF CONTENTS Historical Sketch v Description ¡x Reel Index Reels 1-2 Administration 1 Reel3 Administration cont 1 Advertising 1 Reel 4 Advertising cont 2 Staff 2 Reels 5-9 Staff cont 2 Reel 10 Staff cont 3 White Newspapers and Magazines 3 Black Press 3 Reel 11 Black Press cont 3 Reel 12 Black Press cont 4 Member Newspapers 4 Reels 13-24 Member Newspapers cont 4 Subject Index 9 m Tlh@ Claiydl® A, iam®^ Faipeirs Claude A. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced from the Microfilm Master. UMI Films the Text Directly Firom the Origin

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from themicrofilm master. UMI films the text directly firom the originalor copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing ffom left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photogrtq}hs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for ai^r photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Com pany 300North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346USA 313.'76l-4700 800/521-0600 EYES OFF THE PRIZE; AFRICAN-AMERICANS, THE UNITED NATIONS, AND THE STRUGGLE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS, 1944-1952 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Carol Elaine Anderson, B.A., M.A, ***** The Ohio State University 1995 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Michael J.