"Black Renaissance" Literary Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Negro Press and the Image of Success: 1920-19391 Ronald G

the negro press and the image of success: 1920-19391 ronald g. waiters For all the talk of a "New Negro," that period between the first two world wars of this century produced many different Negroes, just some of them "new." Neither in life nor in art was there a single figure in whose image the whole race stood or fell; only in the minds of most Whites could all Blacks be lumped together. Chasms separated W. E. B. DuBois, icy, intellectual and increasingly radical, from Jesse Binga, prosperous banker, philanthropist and Roman Catholic. Both of these had little enough in common with the sharecropper, illiterate and bur dened with debt, perhaps dreaming of a North where—rumor had it—a man could make a better living and gain a margin of respect. There was Marcus Garvey, costumes and oratory fantastic, wooing the Black masses with visions of Africa and race glory while Father Divine promised them a bi-racial heaven presided over by a Black god. Yet no history of the time should leave out that apostle of occupational training and booster of business, Robert Russa Moton. And perhaps a place should be made for William S. Braithwaite, an aesthete so anonymously genteel that few of his White readers realized he was Black. These were men very different from Langston Hughes and the other Harlem poets who were finding music in their heritage while rejecting capitalistic America (whose chil dren and refugees they were). And, in this confusion of voices, who was there to speak for the broken and degraded like the pitiful old man, born in slavery ninety-two years before, paraded by a Mississippi chap ter of the American Legion in front of the national convention of 1923 with a sign identifying him as the "Champeen Chicken Thief of the Con federate Army"?2 In this cacaphony, and through these decades of alternate boom and bust, one particular voice retained a consistent message, though condi tions might prove the message itself to be inconsistent. -

The Blues Blue

03-0105_ETF_46_56 2/13/03 2:15 PM Page 56 A grammatical Conundrum the blues Using “blue” and “the blues” Glossary to denote sadness is not recent BACKBEAT—a rhythmic emphasis on the second and fourth beats of a measure. English slang. The word blue BAR—a musical measure, which is a repeated rhythmic pattern of several beats, usually four quarter notes (4/4) for the blues. The blues usually has twelve bars per was associated with sadness verse. and melancholia in Eliza- BLUE NOTE—the slight lowering downward, usually of the third or seventh notes, of a major scale. Some blues musicians, especially singers, guitarists and bethan England. The Ameri- harmonica players, bend notes upward to reach the blue note. can writer Washington Irving CHOPS—the various patterns that a musician plays, including basic scales. When blues musicians get together for jam sessions, players of the same instrument used the term the blues in sometimes engage in musical duels in front of a rhythm section to see who has the “hottest chops” (plays best). 1807. Grammatically speak- CHORD—a combination of notes played at the same time. ing, however, the term the CHORD PROGRESSION—the use of a series of chords over a song verse that is repeated for each verse. blues is a conundrum: should FIELD HOLLERS—songs that African-Americans sang as they worked, first as it be treated grammatically slaves, then as freed laborers, in which the workers would sing a phrase in response to a line sung by the song leader. as a singular or plural noun? GOSPEL MUSIC—a style of religious music heard in some black churches that The Merriam-Webster una- contains call-and-response arrangements similar to field hollers. -

Blues Poetry As a Celebration of African American Folk Art

ABSTRACT RUTTER, EMILY R. Blues-Inspired Poetry: Jean Toomer, Sterling Brown and the BLKARTSOUTH Collective. (Under the direction of Professor Thomas Lisk). Adopting the blues to lyric poetry marks an implicit rejection of the conventions of the Anglo-American literary establishment, and asserts that African American folk traditions are an equally valuable source of poetic inspiration. During the Harlem Renaissance, Jean Toomer’s Cane (1923) exemplified the incorporation of African American folk forms such as the blues with conventional English poetics. His contemporary Sterling Brown similarly created hybrid forms in Southern Road (1932) that combined African American oral and aural traditions with Anglo-American ones. These texts suggest that blues music represents a complex and sophisticated lyrical form, and its thematic tropes poignantly express the history and contemporary realities of black Americans. In the late 1960s, members of New Orleans’s BLKARTSOUTH were influenced by African American musical traditions as a reflection of historical experience and lyrical expression, and their poetry emphasizes the importance of the blues. Led by Kalamu Ya Salaam and Tom Dent, these poets were part of the Black Arts Movement whose political objectives emphasized a separation from the conventions of the Anglo-American literary establishment, and their work suggests a rejection of traditional English poetics. Although they did not openly acknowledge their literary debt to Toomer and Brown, Cane and Southern Road laid the lyrical foundation for the blues-inspired poetry of Salaam, Dent and their colleagues. What unites these generations of poets is their adoption of the blues theme of resilience in response to the social, political and cultural issues of their eras. -

Notable Alphas Fraternity Mission Statement

ALPHA PHI ALPHA NOTABLE ALPHAS FRATERNITY MISSION STATEMENT ALPHA PHI ALPHA FRATERNITY DEVELOPS LEADERS, PROMOTES BROTHERHOOD AND ACADEMIC EXCELLENCE, WHILE PROVIDING SERVICE AND ADVOCACY FOR OUR COMMUNITIES. FRATERNITY VISION STATEMENT The objectives of this Fraternity shall be: to stimulate the ambition of its members; to prepare them for the greatest usefulness in the causes of humanity, freedom, and dignity of the individual; to encourage the highest and noblest form of manhood; and to aid down-trodden humanity in its efforts to achieve higher social, economic and intellectual status. The first two objectives- (1) to stimulate the ambition of its members and (2) to prepare them for the greatest usefulness in the cause of humanity, freedom, and dignity of the individual-serve as the basis for the establishment of Alpha University. Table Of Contents Table of Contents THE JEWELS . .5 ACADEMIA/EDUCATORS . .6 PROFESSORS & RESEARCHERS. .8 RHODES SCHOLARS . .9 ENTERTAINMENT . 11 MUSIC . 11 FILM, TELEVISION, & THEATER . 12 GOVERNMENT/LAW/PUBLIC POLICY . 13 VICE PRESIDENTS/SUPREME COURT . 13 CABINET & CABINET LEVEL RANKS . 13 MEMBERS OF CONGRESS . 14 GOVERNORS & LT. GOVERNORS . 16 AMBASSADORS . 16 MAYORS . 17 JUDGES/LAWYERS . 19 U.S. POLITICAL & LEGAL FIGURES . 20 OFFICIALS OUTSIDE THE U.S. 21 JOURNALISM/MEDIA . 21 LITERATURE . .22 MILITARY SERVICE . 23 RELIGION . .23 SCIENCE . .24 SERVICE/SOCIAL REFORM . 25 SPORTS . .27 OLYMPICS . .27 BASKETBALL . .28 AMERICAN FOOTBALL . 29 OTHER ATHLETICS . 32 OTHER ALPHAS . .32 NOTABLE ALPHAS 3 4 ALPHA PHI ALPHA ADVISOR HANDBOOK THE FOUNDERS THE SEVEN JEWELS NAME CHAPTER NOTABILITY THE JEWELS Co-founder of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity; 6th Henry A. Callis Alpha General President of Alpha Phi Alpha Co-founder of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity; Charles H. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

The Harlem Renaissance

THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE P&L 863-Rama Ndiaye[Type text] Page 1 Curriculum Development Project OVERVIEW The Harlem Renaissance was a period in which black intellectuals, poets, musicians and writers explored their cultural identity. In a society where racism was prevalent African Americans lacked economic opportunities. The creation of art, music and poetry was not only a way to economically uplift the race but also to demonstrate racial pride. The cultural movement started at the end of the First World War and ended in the middle of the Great Depression in the 1930s. Many argue that the War expanded economic opportunity in Northern cities because of industrialization and the decrease of European immigrants coming into the United States. The Great Migration in the beginning of the 20th century also played a big role in the birth of the cultural movement. African Americans in the South were experiencing social, cultural and economic oppression so when they found opportunities to escape Jim Crow laws they took their chances. The lack of a political voice and the prevalent racial hatred led many African Americans to express themselves via artistic means. Alain Locke, an African American writer, was the first to come up with the term “New Negro” talking about a spur of young black artist who were going to change the African American culture by demonstrating that their people were not subservient, good for nothing cretins. Other intellectuals such as W.E.B. Du Bois and James Weldon Johnson aided in the expansion of the movement by being spokespeople for the literary youth. -

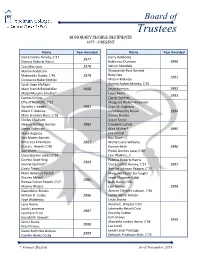

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project

preciate it if you could find it for me.5 I am happy to say that I have read most of zg Dec Gandhi’s works and I have most of them in my library. ‘959 Incidentally, I have written a book entitled Stride Toward Freedom. One of the chapters is devoted to my pilgrimage to nonviolence. Here I try to show the Gand- hian influence in my thinking. I regret that I sent my last copy out a few days ago. If you are interested, however, you may secure a copy from Harper and Brothers. It was published in September, 1958. I will highly appreciate your comments. In answer to your question concerning China, I definitely feel that it should be admitted to the United Nations. We will never have an effective United Nations so long as the largest nation in the world is not in it. Thanks again for your kind letter, and I hope for you a joyous Christmas sea- son and a blessed new year. Yours very truly, Martin L. King, Jr. (Dictated, but not personally signed by Dr. King.) TLc. MLKP-MBU: Box 72. 3. Gandhi, Gandhi’s Letters to a Disciple (New York: Harper, 1950). In a 2 November 1960letter to King, Teek-Frank indicated that she had learned that the book was out of print but offered to lend him her copy the next time he visited New York. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project To Langston Hughes 29 December 1959 Montgomery, Ala. King thanks Hughes for contributing a poem to A. -

Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970

Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Lvovsky, Anna. 2015. Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463142 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge about Homosexuality, 1920–1970 A dissertation presented by Anna Lvovsky to The Committee on Higher Degrees in the History of American Civilization in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of American Civilization Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 – Anna Lvovsky All rights reserved. Advisor: Nancy Cott Anna Lvovsky Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge about Homosexuality, 1920–1970 Abstract This dissertation tracks how urban police tactics against homosexuality participated in the construction, ratification, and dissemination of authoritative public knowledge about gay men in the -

Gwendolyn Brooks 1917–2000

Name _____________________________ Class _________________ Date __________________ The Civil Rights Movement Biography Gwendolyn Brooks 1917–2000 WHY SHE MADE HISTORY Gwendolyn Brooks was an award-winning poet, novelist, and a leader of the Black Arts Movement. She was also the first African American poet to receive a Pulitzer Prize. As you read the biography below, think about the role Gwendolyn Brooks’ writing played in the civil rights movement. Why was her poetry significant? Bettmann/CORBIS © As African Americans worked to bring an end to discrimination, most still lived in poor inner city neighborhoods. The Black Power movement focused on the need for social and economic reforms. A Black Arts Movement also emerged to tell the story of African American life. Poet Gwendolyn Brooks was at the forefront of this movement. Gwendolyn Brooks was born in Topeka, Kansas, in 1917. Two months after her birth, her family moved to Chicago, Illinois, where she would live for the rest of her life. Brooks was a shy child who developed an interest in writing. Her mother encouraged this interest, and teachers helped develop her talent. At an early age, Brooks was published in national magazines and newspapers. After graduation from high school, Brooks entered community college and received an associate’s degree. She worked at many different jobs, from maid to spiritual healer. Later she would write about these experiences. She was also involved in the Youth Council of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and helped found a club for young black artists and writers. Through this club, she met her future husband, poet Henry Blakely. -

158 Kansas History the Hard Kind of Courage: Labor and Art in Selected Works by Langston Hughes, Gordon Parks, and Frank Marshall Davis

Gordon Parks’s American Gothic, Washington, D.C., which captures government charwoman Ella Watson at work in August 1942. Photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 36 (Autumn 2013): 158–71 158 Kansas History The Hard Kind of Courage: Labor and Art in Selected Works by Langston Hughes, Gordon Parks, and Frank Marshall Davis by John Edgar Tidwell hen and in what sense can art be said to require a “hard kind of courage”? At Wichita State University’s Ulrich Museum, from September 16 to December 16, 2012, these questions were addressed in an exhibition of work celebrating the centenary of Gordon Parks’s 1912 birth. Titled “The Hard Kind of Courage: Gordon Parks and the Photography of the Civil Rights Era,” this series of deeply profound images offered visual testimony to the heart-rending but courageous sacrifices made by Freedom Riders, the bombing victims Wat the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, the energized protesters at the Great March on Washington, and other participants in the movement. “Photographers of the era,” the exhibition demonstrated, “were integral to advancing the movement by documenting the public and private acts of racial discrimination.”1 Their images succeeded in capturing the strength, fortitude, resiliency, determination, and, most of all, the love of those who dared to step out on faith and stare down physical abuse and death. It is no small thing that all this was done amidst the challenges of being a black artist or writer seeking self-actualization in a racially charged era.